Embara: Saigon's Youth Arcadia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hotel Reservation

analytica Vietnam 2019 6th International Trade Fair for Laboratory Technology, Analysis, Biotechnology and Diagnostics 03.04.2019 – 05.04.2019 Saigon Exhibition & Convention Center (SECC), Vietnam Hotel Reservation Deadline: Subject to availability 1. Hotel Rex (5* hotel) Deluxe: VND 3.108.000 per room / per night equal US$ 138 per room/ per night, daily breakfast included Premium: VND 3.348.000 per room / per night equal US$ 148 per room/ per night, daily breakfast included Located in the heart of Ho Chi Minh City, the Rex hotel was rebuilt to become one of the city`s most incredible addresses. Rex hotel is a luxury hotel heritage dating back to early 20th century when it was originally opened as a French garage. For over 80 years, the Rex has been as a landmark, as well as a witness of the ups and downs of the city´s history. 2. Hotel Nikko (5* hotel) Deluxe Single: VND 3.393.000 per room / per night equal US$ 145 per room / per night, daily breakfast included Deluxe Double/Twin: VND 3.627.000 per room / per night equal US$ 155 per room / per night, daily breakfast included Hotel Nikko Saigon is a 5-star luxury hotel with 334 rooms, suites and apartments in a high rise 23-story building. Offering excellent services and facilities, we cater for the needs of both business and leisure travelers. Conveniently located near the center of Ho Chi Minh City, only 20 minutes drive from Tan Son Nhat International Airport, the hotel offers easy access to many landmarks, museums and cultural centers and just 10 minutes to city center. -

Asiaancient+ Modern

Ken Spence Photograph: Hot Air Balloons over Bagan, Myanmar Asiaancient + modern P RODUCED BY P R O M O T I O N S traveller | promotion Asiaancient + modern China Immerse yourself in the buzzing and vibrant founder and CEO of Affordable Art it housed the Shanghai Club, an China, who gives expert insights exclusive retreat for British gentry. cities of Beijing and Shanghai on Chinese art, along with the history of this Bauhaus-style, former munitions factory complex. Private rban China is where the studio visits can also be arranged. Shanghai’s architectural heritage past, present and future includes a fine portfolio of Art Deco intersect as this vast buildings, from the brooding Park nation hurtles towards Hotel (parkhotelshanghai.cn) to the Uglobal superpower status. A younger city, whose founding pencil-slim Bank of China. Shanghai The contrasting historical and principal was commerce rather than will host the 2015 World Congress contemporary narratives of Beijing imperial decree, Shanghai has a on Art Deco, and Patrick Cranley, and Shanghai – China's two primary penchant for showiness, apparent founder of Historic Shanghai cities – is where the real fun begins. in its angular skytowers and glitzy (facebook.com/historic.shanghai), will boutiques. Stylish stays include be your Art Deco guide. Architect the slick, state-of-the-art Banyan Spencer Dodington of Luxury Tree Shanghai on the Bund Concierge (luxuryconciergechina. Beijing’s imperial legacy is (banyantree.com) with spectacular com) offers expert walks, through old underscored by the Forbidden views, and the neo-classical Waldorf Shanghai’s neighbourhoods and its City and Temple of Heaven, while Astoria Shanghai on the Bund futuristic constructs, as well as private Maoism’s imprint hangs over (waldorfastoria.com) – which recalls shopping trips for design pieces from Tiananmen Square. -

Research Report

HOSPITALITY SECTOR Edition 2018 RESEARCH REPORT This project is co-funded by the European Union USEFUL CONTACTS MORE INFORMATION EU-Vietnam Business Network (EVBN) General Statistics Office of Vietnam: 15th Floor, 5B Ton Duc Thang, District 1 http://www.gso.gov.vn Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam Vietnam Customs Statistics: T: +84 (0)28 38239515 http://www.customs.gov.vn www.evbn.org Vietnam Trade Promotion Agency (Vietrade): en.vietrade.gov.vn World Bank Vietnam: http://www.worldbank.org/en/country/vietnam The Landmark, 15th floor, 5B Ton Duc Thang St., District 1, This publication was produced with the assistance of the European Union. Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam The content of this publication is the sole responsibility of EVBN and Tel. +84 (0)28 3823 9515 Fax +84 (0)28 3823 9514 can in no way be taken to reflect the views of the European Union. www.evbn.org EVBN The Hospitality market in Vietnam 2 CONTENTS Contents 3 List of Abbreviations 4 Currency Exchange 4 List of figures 5 Executive Summary 6 Chapter 1: Vietnam Overview Chapter 4: Profile of End Consumer Geo-demographics 8 and Distribution Channels Vietnam’s Economy 10 Profile of end consumer 31 Structure of consumption expenditures 12 Distribution channels 32 Price Structure 33 Chapter 2: Overview of Hospitality in Vietnam Chapter 5: Regulatory and Legal Vietnam’s tourism: a rising hotspot 14 Framework Accommodation industry: the rise of 14 Regulatory and legal framework that 36 luxury hotels and resorts applies to investors in the F&B and hospitality sectors Food and Beverage 17 Different -

Thematic Indexes

1,000 Places to See Before You Die By Patricia Schultz T HEMA T IC I NDEXES NOTE: These 12 indexes serve as a companion to 1,000 Places to See Before You Die: The New Full-Color Second Edition (Workman Publishing, 2011). They categorize the book’s entries by type of experience. C ONTENTS A CTIVE T R AVEL , W ILDLIFE , A ND A DVENTURE 2 Ballooning • Bicycling • Bird-Watching • Bungee Jumping and Base Jumping • Camel Rides • Canoeing, Kayaking, Rafting, and Jet-Boating • Caves and Caving • Climbing • Dogsledding • Elephant Rides • Falconry • Fishing • Golfing• Hang Gliding • Hiking and Trekking • Horseback Riding • Ice Skating • Kite Boarding and Kite Surfing • Safaris and Expeditions • Sailing • Scuba, Snorkel, and Other Aquatic Adventures • Skiing • Sleigh and Toboggan Run • Snowmobiling • Surfing and Windsurfing • Tennis • Whale-Watching A NCIENT W ORLDS : P YR A MIDS , R UINS , A ND L OST C ITIES 12 C ULIN A RY E X P ERIENCES 14 F ESTIVA LS A ND S P ECI A L E VENTS 24 G LORIES OF N ATURE : G A RDENS , P A RKS A ND W ILDERNESS P RESERVES , A ND N ATUR A L W ONDERS 26 Gardens • Parks and Wilderness Preserves • Natural Wonders G OR G EOUS B E A CHES A ND G ETawaY I SL A NDS 31 Beaches and Seashores • Islands H OTELS , R ESORTS , E CO -L OD G ES , A ND I NNS 34 L IVIN G H ISTORY : C A STLES A ND P A L A CES , H ISTORIC A L S ITES 52 Castles and Palaces • Historical Sites R O A D waYS , R A ILwaYS , A ND W ATERwaYS 56 Scenic Drives • Train Trips • Ships and Cruises ACTIVE TRAVEL, WILDLIFE, AND ADVENTURE 2 S A CRED P L A CES 58 S P LENDOR -

Travel, Hotel and Sight Seeing Information

SOME GENERAL INFORMATION OF VIETNAM AND HO CHI MINH CITY Country information Full name of the country: Socialist Republic of Vietnam Area: 330.991 sq.km/127.796 sq. miles Population: about 82 million Languages: Vietnamese is the official language (English, French, Russia and Chinese area also spoken) Time zone: GTM + 7 Country code: 84 Religion: Buddhism is the principal faith Currency: VN (Vietnam Dong), USD and most credit cards accepted at major hotels, restaurants. Ho Chi Minh City Geography In the core of the Mekong Delta, Ho Chi Minh City, formerly known as Saigon, is second the most important in Vietnam after Hanoi. It is not only a commercial center but also a scientific, technological, industrial and tourist center. The city is bathed by many rivers, arroyos and canals, the biggest river being the Saigon River. The Port of Saigon, established in 1862, is accessible to ships weighing up to 30,000 tons, a rare advantage for an inland river port. Climate:The climate is generally hot and humid. There are two distinctive seasons: the rainy season, from May to November, and the dry season, from December to April. The annual average temperature is 27ºC. The hottest month is April and the lowest is December. It is warm all year. History Many centuries ago, Saigon was already a busy commercial center. Merchants from China, Japan and many European countries would sail upstream the Saigon River to reach the islet of Pho, a trading center. In the year of 1874, Cho Lon merged with Saigon, forming the largest city in the Indochina. -

Auscham Vietnam

Hotels & Hospitality Group | July 2017 Vietnam Spotlight on the Accommodation & Tourism Industry CHINA Sapa Hanoi Halong HAINAN ISLAND Yangon Hue THAILAND Foreword Danang Hoi An Vietnam has undergone an astonishing 30 years of development. The World Bank's outlook for the Vietnamese economy remains highly positive, with average GDP growth of around 6% forecast CAMBODIA annually until 2020, whilst Oxford Economics forecast that by Nha Trang Dalat 2020 Vietnam’s economy will be growing faster than China, Indonesia, Malaysia, Philippines, Singapore and Thailand. GULF OF Phan Thiet THAILAND Economic and political reforms have spurred rapid growth, previously high inflation is now under control with the average Ho Chi Minh City inflation rate in 2014 – 2016 standing at 2.5% and the exchange Phu Quoc rate being stable over recent years. These factors continue to transform the country, with the middle class expected to grow by 18% from 2016 – 2020, providing one of many catalysts for the rapidly growing tourism industry. Vietnam's wealthiest are also set to get much richer. In fact, the dramatic growth of "Ultra High Net Worth Individuals" in Asia (which is typically regarded as someone with a net worth of above USD 30 million) is set to be reinforced by stellar growth rates in Vietnam, which is expected to see its ultra-wealthy population rise by the highest rate of growth in the world. Hanoi Vietnam’s rapid economic development has been led by Capital of Vietnam an industrial renaissance, particularly as multi-national manufacturers look to diverse their operations across developing Asia in a so-called ‘China + 1’ strategy. -

Ho Chi Minh City HO CHI MINH CITY

Ho Chi Minh City I.H.T. HOTEL CONTINENTAL , 132-134 Dong Khoi St., Dist. 1, Ho Chi Minh City, HO CHI MINH CITY Vietnam. ,Tel: (84.8) 38 299 201 ,Fax: (84.8) 38 290 936, Email: [email protected] , http://www.continentalhotel.com.vn HOTEL EQUATORIAL HO CHI MINH CITY , 242 Tran Binh Trong , District 5 , Ho Chi Minh City , Vietnam , Tel: +84 8 3839 7777 , Fax: +84 8 3839 0011, Email: [email protected] , www.equatorial.com/hcm HOTEL MAJESTIC,Address: 1 Dong Khoi Str., Dist. 1, Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam, Tel: (84-8) 3829 5517 , Fax: (84-8) 3829 5510 , E-Mail: [email protected] ,www.majesticsaigon.com.vn KIMDO-ROYAL CITY HOTEL,133 Nguyen Hue Ave., Dist.1, Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam, Tel:(84 8) 3822 5914, Fax: (84 8) 3822 5913 , Email : [email protected] , www.kimdohotel.com.vn METROPOLE HOTEL , 148 Tran Hung Dao Ave, District 1, Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam, Tel: (84-8) 6 295 8944, Fax: (84-8) 3 920 1960, Email: [email protected] , http://www.metropolesaigon.com NEW WORLD HOTEL SAIGON , 76 Le Lai St., Dist.1, Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam , Telephone: (84-8) 822 8888 , Fascimile: (84-8) 823 0710 , Email: [email protected] , Website: http://www.newworldhotels.com OSCAR SAIGON HOTEL ,68A Nguyen Hue Ave., Dist.1, Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam, Tel: (84-8) 38292959, Fax:(84-8) 38222958, http://www.oscar- saigonhotel.com PARKROYAL SAIGON, 309B-311 Nguyen Van Troi, Tan Binh District, Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam, T: (84) 8 3 842 1111, F: (84) 8 3 842 4363, http://www.parkroyalhotels.com PARK HYATT SAIGON, 2 Lam Son -

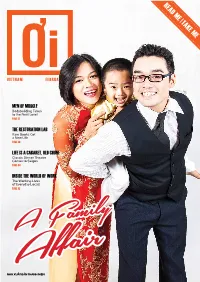

February 2014

COMPLIMENTARY COPY ENTARY COPY READ ME TAKE ME COMPLIMENTARY COPY COMPLIMENTARY COPY COMPLIMENT VIETNAM FEBRUARY 2014 MEN OF MUSCLE Bodybuilding Taken to the Next Level PAGE 27 THE RESTORATION LAB Rare Books Get a New Life PAGE 30 LIFE IS A CABARET, OLD CHUM Classic Dinner Theater Comes to Saigon PAGE 44 INSIDE THE WORLD OF WORK The Working Lives of Everyday Locals PAGE 92 A Family Affair 1 2 3 CO M PLIME ENTA N R TAR Y C O PREAD Y ME TAKE ME Y C O PY COMP COMP L IMEN L I M T E N T A R Y C O P A R Y C O P Y COMPLIM Y E NT VIETNAM FEBRUARY 2014 MEN OF MUSCLE Bodybuilding Taken to the Next Level PAGE 27 THE RESTORATION LAB Rare Books Get EVERYWHERE YOU GO a New Life PAGE 30 LIFE IS A CABARET, OLD CHUM Classic Dinner Theater Comes to Saigon PAGE 44 INSIDE THE WORLD OF WORK The Working Lives of Everyday Locals PAGE 92 Director XUAN TRAN A Family Business Consultant ROBERT STOCKDILL [email protected] Affair 093 253 4090 1 Managing Editor CHRISTINE VAN [email protected] This Month’s Cover Image: Ngoc Tran Deputy Editor JAMES PHAM Model: The Tran Family [email protected] Make Up: Huyen Phan Researcher GEORGE BOND [email protected] Associate Publisher KHANH NGUYEN [email protected] Graphic Artist HIEN NGUYEN [email protected] Staff Photographers NGOC TRAN ADAM ROBERT YOUNG Publication Manager HANG PHAN [email protected] 097 430 9710 For advertising please contact: JULIAN AJELLO [email protected] 093 700 9910 NGAN NGUYEN [email protected] 090 279 7951 ƠI VIỆT NAM JIMMY VAN DER KLOET [email protected] NHÀ XUẤT BẢN THANH -

6 Days Hochiminh – Cuchi Tunnels – Dalat – Muine Exploration Valid Till Sept 2020

6 Days Hochiminh – Cuchi Tunnels – Dalat – Muine Exploration Valid till Sept 2020 Tour code: DA16-6D/2019 Route: Hochiminh – Cu Chi Tunnels – Dalat – Muine Duration: 6 days Start from Hochiminh and end of Hochiminh DAY 1: HOCHIMINH ARRIVAL (D) Arrive in Ho Chi Minh City, welcome by our guide and transfer to hotel for check in. Ho Chi Minh City formerly named Saigon is the largest city and economic center of Vietnam always bustled with activities of modern life. It is where businesses converge and shoppers indulge themselves into unlimited choices. However the city also carries with it a rich historical legacy in contrast with its dazzling glamor. Afternoon, take a half-day city tour to visit Saigon Notre-Dame Basilica, a neo-Roman cathedral built by the colonial French with materials entirely imported from Marseilles, Saigon Central Post Office, which was designed and constructed in the early 20th Century by the famous French architect Gustave Eiffel. Dinner at the local restaurant. Overnight at hotel in Hochiminh. DAY 2: HOCHIMINH – CUCHI TUNNELS – MUINE (B/L/D) Hochiminh – Muine: 220km – 4 hours 10 minutes driving Morning, take a half-day tour to the Cu Chi Tunnels, 75 km Northwest of downtown Ho Chi Minh City, which were once a major underground hideout and resistance base of Viet Cong forces during the two wars against the French and later on Americans. The tunnels, entirely hand-dug, formed a highly intricate network of interlinked multilevel passageways at times stretched as far as the Cambodian border and totaling over 120 km in length. Its complexity was beyond imagination containing meeting rooms, kitchens, wells, clinics, schools, depots, trenches and emergency exits all aimed for guerrilla warfare. -

Fine Hotels and Resorts 2019.Pdf

® 2019 Fine Hotels & Resorts and The Hotel Collection and Fine Hotels & Resorts 2019 Fine Hotels & Resorts® Velaa Private Island, The Fontenay Hamburg, Malé, Maldives Hamburg, Germany — — Fine Hotels & Resorts Fine Hotels & Resorts The Hotel Collection The Cape, A Thompson Hotel, Los Cabos, Mexico — The Hotel Collection An Introduction 3 How, where, and why we travel is changing, and your Platinum Card® Membership is always evolving to better serve you. The 2019 Fine Hotels & Resorts program highlights. From renowned To book your next vacation, and The Hotel Collection programs chefs and spectacular pools to spa simply visit amextravel.com include more than 1,700 hotels, experiences that take wellness to a or call Platinum Travel Service each carefully chosen with Card whole new level, explore the untold at 1-800-525-3355. Members like you in mind. stories and discover hidden gems that lie just a booking away. From some of the world’s most luxurious properties to eclectic Browse this book and take note and boutique-chic stays, we’ve of the designated hotel programs combined these two hotel collections to see which of your Platinum Card into one guide so you can easily Member benefits apply. Head online see all the places you can travel to to our digital directories for even while enjoying benefits from your more inspiration and, when you’re American Express Platinum Card. ready to book your next vacation, simply visit amextravel.com or This year, we also invite you to call Platinum Travel Service at dig a little deeper as we focus on 1-800-525-3355.