Author Final Version

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Yankees Pull All-Nighter, Beat Reds 10-4

SECTION B VISIT SAMOA NEWS ONLINE @ SAMOANEWS.COM TUESDAY MAY 09, 2017 CLASSIFIEDS • CARTOONS • ALOHA BRIEFS & MORE ▼ ▼ ▼ ▼ ▼ ▼ ▼ ▼ ▼ ▼ ▼ ▼ ▼ ▼ ▼ ▼ ▼ ▼ ▼ ▼ ▼ ▼ ▼ ▼ ▼ ▼ ▼ ▼ ▼ ▼ ▼ ▼ ▼ ▼ ▼ ▼ ▼ ▼ ▼ ▼ ▼ ▼ ▼ ▼ ▼ ▼ ▼ ▼ ▼ ▼ ▼ ▼ ▼ ▼ ▼ ▼ ▼ ▼ ▼ ▼ ▼ ▼ ▼ ▼ ▼ ▼ ▼ ▼ ▼ ▼ ▼ ▼ ▼ ▼ ▼ ▼ ▼ ▼ ▼ ▼ No snoozing: 2 C headline text goes in C M Y K Yankees pull the box here all-nighter, beat Reds 10-4 CINCINNATI (AP) — The streak. Yankees know how to pull an “That’s a big boost for them,” all-nighter and come up aces. Reds manager Bryan Price said. Brett Gardner and Matt “They play 18 innings, and then Holliday homered, Masahiro their starter goes seven. That Tanaka won his fifth consecu- puts them in a lot better shape tive start and New York shook for tomorrow.” off a long game and a short Gary Sanchez got the Yan- night’s sleep, beating the Cin- kees going with his bases-loaded cinnati Reds 10-4 on Monday single in the first off Rookie night for its sixth victory in a Davis (1-2), a former Yankees row. prospect. Didi Gregorius also The Yankees have the best drove in a pair off Davis, who record in the majors at 21-9 and went to the Reds in the trade for are 12 games over .500 for the closer Aroldis Chapman after first time since the end of the the 2015 season. 2015 season. Gardner and Holliday con- Better yet, they were awake nected in the eighth inning as to enjoy all of it. the Yankees pulled away. New York Yankees shortstop Didi Gregorius, center left, second baseman Starlin Castro, center, “Guys were really fatigued,” There were some sloppy and third baseman Ronald Torreyes, right, celebrate after closing the ninth inning of a baseball manager Joe Girardi said. -

T Tenacity, Work

~~,w~~t .g.~. 1442·1992 SESQUICENTENNIAL Saint Ma~:S Colleg~ NOTRE DAME• INDIANA ~ VOL. XXIV NO. 35 I FRIDAY , OCTOBER 11, 1991 I I - THE INDEPENDENT NEWSPAPER SERVING NOTRE DAME AND SAINT MARY'S Clark stresses f tenacity, work • Conference I page 5 By BECKY BARNES News Writer "It's all about being the best at whatever you are," said former New Jersey high school principal Joe Clark, in his lecture last night advocating hard work, determination and tenacity as the means for self-ad vancement. "Be sure that you are in control of your own destiny," said Clark. "If you end up being nothing don't blame the bureaucracy, the black man, the white man - blame yourself." Clark, now an assistant superintendent of schools, was principal of East Side High in see CLARKI page 6 Saint Mary's freshmen hold run-off elections By AMY GREENWOOD Photo courtesy of Public Relations and Information SMC News Editor This postcard of the Main Building will go on sale Tuesday during a special ceremony in the Monogram Room of the Joyce A. C. C. ] The postcard will also be available at the Notre Dame post office from 8 a.m. to 4:30 p.m. The Saint Mary's freshman class held its second run-off election for president and vice president last night. The class of 1995 elected Megan Zimmer Commemorative postal card to be issued as its president, and Heather Sterling as Special to The Observer bile trailer outside the post office, the Field House Mall, and vice president. the Alumni Senior Club. -

Kruger Vikings Astros

PRESS & DAKOTAN SATURDAY, AUGUST 22, 2015 SPORTS :PAGE 13 SPORTS DIGEST Morgan, an outfi elder, played for DECEMBER: 3, vs. Drake (7 p.m.); 5, vs. Portland State (2 p.m.); 8, at San Jose there will be age group awards as well. Tereshinski Field Turf Project State (TBA); 12, vs. Washington (8 p.m.); 17, vs. Dakota Wesleyan (7 p.m.); 19, at Durango High School, earning her team’s North Dakota (2 p.m.); 22, at Illinois (TBA) Packet pickup will be from 9-9:50 a.m. on the morning of Receives Twins Grant Most Improved honor as a junior. JANUARY: 1, vs. Denver (noon); 6, at Oral Roberts (7 p.m.); 9, vs. Omaha (1:30 the event near the south picnic shelter at Memorial Park. The The Bob Tereshinski Field Turf Project recently learned “We believe Gabby has a good work p.m.); 14, at North Dakota State (7 p.m.); 17, at South Dakota State (2 p.m.); 21, vs. Run/Walk begins at 10 a.m. ethic and will continue to improve,” said Fort Wayne (7 p.m.); 23, vs. IUPUI (1:30 p.m.); 27, at Western Illinois (7 p.m.); 30, For more information about the event and about early reg- that it was the recipient of a 2015 Twins Fields for Kids Grant vs. North Dakota State (4:30 p.m.) through the Minnesota Twins Community Fund. The grant, MMC softball coach Albert Fernandez. FEBRUARY: 5, at Denver (8 p.m.); 7, at Omaha (2 p.m.); 13, vs. Oral Roberts istration rates, call 605-665-4811 or email womensshelter@ totaling $5,000 will go towards the fi eld turf project that is “She is a solid student and has the desire (2 p.m.); 18, vs. -

Weekly Notes 072817

MAJOR LEAGUE BASEBALL WEEKLY NOTES FRIDAY, JULY 28, 2017 BLACKMON WORKING TOWARD HISTORIC SEASON On Sunday afternoon against the Pittsburgh Pirates at Coors Field, Colorado Rockies All-Star outfi elder Charlie Blackmon went 3-for-5 with a pair of runs scored and his 24th home run of the season. With the round-tripper, Blackmon recorded his 57th extra-base hit on the season, which include 20 doubles, 13 triples and his aforementioned 24 home runs. Pacing the Majors in triples, Blackmon trails only his teammate, All-Star Nolan Arenado for the most extra-base hits (60) in the Majors. Blackmon is looking to become the fi rst Major League player to log at least 20 doubles, 20 triples and 20 home runs in a single season since Curtis Granderson (38-23-23) and Jimmy Rollins (38-20-30) both accomplished the feat during the 2007 season. Since 1901, there have only been seven 20-20-20 players, including Granderson, Rollins, Hall of Famers George Brett (1979) and Willie Mays (1957), Jeff Heath (1941), Hall of Famer Jim Bottomley (1928) and Frank Schulte, who did so during his MVP-winning 1911 season. Charlie would become the fi rst Rockies player in franchise history to post such a season. If the season were to end today, Blackmon’s extra-base hit line (20-13-24) has only been replicated by 34 diff erent players in MLB history with Rollins’ 2007 season being the most recent. It is the fi rst stat line of its kind in Rockies franchise history. Hall of Famer Lou Gehrig is the only player in history to post such a line in four seasons (1927-28, 30-31). -

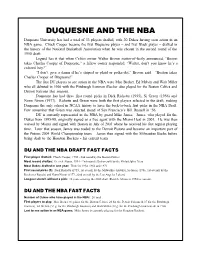

DUQUESNE and the NBA Duquesne University Has Had a Total of 33 Players Drafted, with 20 Dukes Having Seen Action in an NBA Game

DUQUESNE AND THE NBA Duquesne University has had a total of 33 players drafted, with 20 Dukes having seen action in an NBA game. Chuck Cooper became the first Duquesne player – and first Black player – drafted in the history of the National Basketball Association when he was chosen in the second round of the 1950 draft. Legend has it that when Celtics owner Walter Brown matter-of-factly announced, “Boston takes Charles Cooper of Duquesne,” a fellow owner responded, “Walter, don’t you know he’s a colored boy?” “I don’t give a damn if he’s striped or plaid or polka-dot,” Brown said. “Boston takes Charles Cooper of Duquesne!” The first DU players to see action in the NBA were Moe Becker, Ed Melvin and Walt Miller who all debuted in 1946 with the Pittsburgh Ironmen (Becker also played for the Boston Celtics and Detroit Falcons that season). Duquesne has had three first round picks in Dick Ricketts (1955), Si Green (1956) and Norm Nixon (1977). Ricketts and Green were both the first players selected in the draft, making Duquesne the only school in NCAA history to have the back-to-back first picks in the NBA Draft. Few remember that Green was selected ahead of San Francisco’s Bill Russell in ‘56. DU is currently represented in the NBA by guard Mike James. James, who played for the Dukes from 1995-98, originally signed as a free agent with the Miami Heat in 2001. He was then waived by Miami and signed with Boston in July of 2003 where he received his first regular playing time. -

Texas Rangers (0-3) at Milwaukee Brewers (0-2) LHP Ross Detwiler (0-0, ––) Vs

Texas Rangers (0-3) at Milwaukee Brewers (0-2) LHP Ross Detwiler (0-0, ––) vs. RHP Wily Peralta (0-0, ––) Spring #4 • Road #2 (0-1) • Sat., March 7, 2015 • Maryvale Ballpark • 2:05 p.m. CDT • 105.3 FM / MLBN* TODAY’S SCHEDULED PITCHERS TEXAS RANGERS MILWAUKEE SPRING TRAINING AT A GLANCE 47 Ross Detwiler LHP 38 Wily Peralta RHP 22 Nick Martinez RHP 51 Jonathan Broxton RHP Record .......................................................................................0-3 25 Jamey Wright RHP 21 Jeremy Jeffress RHP Home .........................................................................................0-2 53 Luke Jackson RHP 29 Jim Henderson RHP Road ..........................................................................................0-1 76 Martire Garcia LHP *70 Juan Perez LHP In Surprise .................................................................................0-3 * - minor league camp Away from Surprise ...................................................................0-0 Current streak ............................................................................. L3 TOMORROW’S SCHEDULED PITCHERS VS. INDIANS Last 5 games .............................................................................0-3 TEXAS RANGERS CLEVELAND 63 Anthony Bass RHP 58 T.J. House LHP Longest winning streak .............................................................. NA 44 Spencer Patton RHP 43 Josh Tomlin RHP Longest losing streak......................................................3 (current) 21 Kyuji Fujikawa RHP 37 Cody Allen RHP TEX scores -

Journal of Business “Who Are the Best Managers in the United States?”

Journal of Business “Who Are the Best Managers in the United States?” Spring 2018 Editor, John DeSpagna An E-Publication of the Accounting and Business Administration Department at Nassau Community College Foreword It is with great pleasure we bring to you the second edition of the Journal of Business with the theme, “Who Are the Best Managers in the United States?” Our primary objective in publishing our students’ essays is to provide a forum for students and to demonstrate their understanding of the concept of the best leaders in this country. We also received and welcomed submissions from faculty members. The 24 submissions include a wide variety of examples of who these great managers are. This is our second publication, which will be distributed electronically to the Nassau Community College community. Bound paper copies are also available upon request by contacting John DeSpagna at [email protected]. We look forward to continuing to publish this Journal of Business annually. I am sure you will enjoy reading through this publication, and if you have any comments, questions or suggestions, please feel free to contact me at [email protected]. In closing, thank you to our students and faculty members who submitted their essays to make this happen. Sincerely, John DeSpagna Professor John DeSpagna Accounting and Business Administration Department [email protected] 2 Acknowledgments I would like to acknowledge the contributions of those who helped make this publication happen. The students of Nassau Community College are to be commended for the essays they submitted. We also had essays submitted by five faculty members of Nassau Community College. -

My Replay Baseball Encyclopedia Fifth Edition- May 2014

My Replay Baseball Encyclopedia Fifth Edition- May 2014 A complete record of my full-season Replays of the 1908, 1952, 1956, 1960, 1966, 1967, 1975, and 1978 Major League seasons as well as the 1923 Negro National League season. This encyclopedia includes the following sections: • A list of no-hitters • A season-by season recap in the format of the Neft and Cohen Sports Encyclopedia- Baseball • Top ten single season performances in batting and pitching categories • Career top ten performances in batting and pitching categories • Complete career records for all batters • Complete career records for all pitchers Table of Contents Page 3 Introduction 4 No-hitter List 5 Neft and Cohen Sports Encyclopedia Baseball style season recaps 91 Single season record batting and pitching top tens 93 Career batting and pitching top tens 95 Batter Register 277 Pitcher Register Introduction My baseball board gaming history is a fairly typical one. I lusted after the various sports games advertised in the magazines until my mom finally relented and bought Strat-O-Matic Football for me in 1972. I got SOM’s baseball game a year later and I was hooked. I would get the new card set each year and attempt to play the in-progress season by moving the traded players around and turning ‘nameless player cards” into that year’s key rookies. I switched to APBA in the late ‘70’s because they started releasing some complete old season sets and the idea of playing with those really caught my fancy. Between then and the mid-nineties, I collected a lot of card sets. -

April 23, 2021 at Target Field, Minneapolis, MN -- GAME #20/ROAD #13 RHP JT BRUBAKER (2-0, 1.76 ERA) Vs. LHP J.A. HAPP (0-0, 3.12 ERA)

PITTSBURGH PIRATES (9-10) vs. MINNESOTA TWINS (6-11) April 23, 2021 at Target Field, Minneapolis, MN -- GAME #20/ROAD #13 RHP JT BRUBAKER (2-0, 1.76 ERA) vs. LHP J.A. HAPP (0-0, 3.12 ERA) THE PIRATES...have won three of their last four games and six of their last nine...Have gone 8-4 in their last 12 games after losing six in a row...Began the season with a 5-3 victory at Wrigley Field on 4/1...Were 4-15 after 19 games in 2020 (4-16 after 20). SERIES-LY SPEAKING: The Pirates have gone 3-0-1 in their last four series after dropping their first two...They have won BUCS WHEN... back-to-back road series for the first time since winning four in a row in Colorado (August 29-Sept 1) and three-of-four in Last five games ................3-2 San Francisco (September 9-12) during the 2019 season. Last ten games .................6-4 ROOKIE LONG BALLS: Phillip Evans shares the Major League lead in home runs (four) by a rookie this season...His four home runs are also tied for the most ever by a Pittsburgh rookie during the first month of the season (March/April)...Josh Bell Leading after 6 .................7-0 hit four as a rookie in 2017 on his way to tying the club record for most home runs hit by a rookie in a single season (26). Tied after 6 ....................2-1 PEN PALS: The Bucco bullpen has posted a 3-0 record and a 1.05 ERA (34.1ip/4er) in the last nine games...That marks the Trailing after 6 .................0-9 lowest bullpen ERA in the National League in that time and the second-lowest in the Majors behind Seattle (0.60)...Kyle Crick has allowed one hit in his first seven games (21 at bats)...Duane Underwood, Jr. -

From This Day Forward

Lakeport driver COMMERCE races for a cure Wednesday Volvo wagon gets a makeover ...................................Page 3 .............Page 6 June 18, 2008 INSIDE Mendocino County’s Obituaries The Ukiah local newspaper ..........Page 2 Thursday: Partly sunny; H 88º L 49º 7 58551 69301 0 Friday: Mostly sunny H 84º L 52º 50 cents tax included DAILY JOURNAL ukiahdailyjournal.com 14 pages, Volume 150 Number 70 email: [email protected] FOLLOW-UP Arrest made From this day forward... in railroad More than a dozen same-sex couples exchange marriage vows in Ukiah track killing Dead man identified By BEN BROWN The Daily Journal The Ukiah Police Department has arrested Alva Thomas Reeves on charges of murder in the death of a man whose body was found in the railroad siding north of Perkins Street Saturday and who police are now identifying as Gerald Knight, 51, of Ukiah. According to police reports, Reeves was seen walking into the Quest Mart at 915 N. State St. at around 10 p.m. Monday by Officer Tyler Schapmire, who was on routine patrol. Reeves was arrested on suspicion of murder without incident and Reeves was booked into the Mendocino County Jail, where he is being held without bail. Reeves is alleged to have killed Knight, whose body was found near the railroad tracks off Mason Street north of Perkins Street by a local resident early Saturday morning. Ukiah Police Capt. Trent Taylor said Knight appeared to have died from a vio- lent physical assault. It is not clear if any weapons were used in the attack, accord- ing to police reports. -

Maryland Players Selected in Major League Baseball Free-Agent Drafts

Maryland Players selected in Major League Baseball Free-Agent Drafts Compiled by the Maryland State Association of Baseball Coaches Updated 16 February 2021 Table of Contents History .............................................................................. 2 MLB Draft Selections by Year ......................................... 3 Maryland First Round MLB Draft Selections ................. 27 Maryland Draft Selections Making the Majors ............... 28 MLB Draft Selections by Maryland Player .................... 31 MLB Draft Selections by Maryland High School ........... 53 MLB Draft Selections by Maryland College .................. 77 1 History Major League Baseball’s annual First-Year Player Draft began in June, 1965. The purpose of the draft is to assign amateur baseball players to major league teams. The draft order is determined based on the previous season's standings, with the team possessing the worst record receiving the first pick. Eligible amateur players include graduated high school players who have not attended college, any junior or community college players, and players at four-year colleges and universities three years after first enrolling or after their 21st birthdays (whichever occurs first). From 1966-1986, a January draft was held in addition to the June draft targeting high school players who graduated in the winter, junior college players, and players who had dropped out of four-year colleges and universities. To date, there have been 1,170 Maryland players selected in the First-Year Player Drafts either from a Maryland High School (337), Maryland College (458), Non-Maryland College (357), or a Maryland amateur baseball club (18). The most Maryland selections in a year was in 1970 (38) followed by 1984 (37) and 1983 (36). The first Maryland selection was Jim Spencer from Andover High School with the 11th overall selection in the inaugural 1965 June draft. -

Texas Rangers

Texas Rangers (1-2-1) at Chicago White Sox (3-2) San Diego Padres (3-3) at Texas Rangers (1-3-1) Texas Rangers (1-3-1) at Oakland Athletics (2-3-1) RHP Tyson Ross (0-0, 9.00) vs. RHP Bartolo Colón (0-0, ––) RHP Clayton Blackburn (0-0, 0.00) vs. RHP Jharel Cotton (0-0, 0.00) LHP Matt Moore (0-0, ––) vs. RHP Lucas Giolito (0-0, ––) Spring Games #6-7/Home #3 (1-1) • Thurs., March 1, 2018 • Surprise Stadium • Spring Games #6-7/Road #4 (0-2-1) • Thurs., March 1, 2018 • Hohokam Park • 2:05 p.m. CT • Webcast 2:05 p.m. CDT • No TV / Radio Spring #5 • Road #3 (0-1-1) • Wed., February 28, 2018 • Camelback Ranch • 2:05 p.m. CT • Webcast / No TV TODAY’S SCHEDULED PITCHERS - SURPRISE TEXAS RANGERS SAN DIEGO SPRING TRAINING AT A GLANCE 40 Bartolo Colón RHP 38 Tyson Ross RHP 56 Austin Bibens-Dirkx RHP 32 Chris Young RHP Record ....................................................................................1-3-1 43 Tony Barnette RHP 62 Walker Lockett RHP Home .........................................................................................1-1 74 Brett Martin LHP 72 Cal Quantrill RHP Road .......................................................................................0-2-1 32 Kevin Jepsen RHP 53 Kazuhisa Makita RHP 60 Erik Goeddel RHP In Surprise .................................................................................1-1 Away from Surprise ................................................................0-2-1 TODAY’S SCHEDULED PITCHERS - MESA Current streak ............................................................................. L1 TEXAS RANGERS OAKLAND Last 5 games ..........................................................................1-3-1 47 Clayton Blackburn RHP 45 Jharel Cotton RHP Longest winning streak .......................................................1 (2/25) 48 Paolo Espino RHP 60 Andrew Triggs RHP 79 David Hurlbut LHP 46 Santiago Casilla RHP Longest losing streak......................................................1 (current) 45 Nick Gardewine RHP 31 Liam Hendriks RHP TEX scores 1st/Opp.