Steinbrenner: the Last Lion of Baseball Dennis P

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Baseball Classics All-Time All-Star Greats Game Team Roster

BASEBALL CLASSICS® ALL-TIME ALL-STAR GREATS GAME TEAM ROSTER Baseball Classics has carefully analyzed and selected the top 400 Major League Baseball players voted to the All-Star team since it's inception in 1933. Incredibly, a total of 20 Cy Young or MVP winners were not voted to the All-Star team, but Baseball Classics included them in this amazing set for you to play. This rare collection of hand-selected superstars player cards are from the finest All-Star season to battle head-to-head across eras featuring 249 position players and 151 pitchers spanning 1933 to 2018! Enjoy endless hours of next generation MLB board game play managing these legendary ballplayers with color-coded player ratings based on years of time-tested algorithms to ensure they perform as they did in their careers. Enjoy Fast, Easy, & Statistically Accurate Baseball Classics next generation game play! Top 400 MLB All-Time All-Star Greats 1933 to present! Season/Team Player Season/Team Player Season/Team Player Season/Team Player 1933 Cincinnati Reds Chick Hafey 1942 St. Louis Cardinals Mort Cooper 1957 Milwaukee Braves Warren Spahn 1969 New York Mets Cleon Jones 1933 New York Giants Carl Hubbell 1942 St. Louis Cardinals Enos Slaughter 1957 Washington Senators Roy Sievers 1969 Oakland Athletics Reggie Jackson 1933 New York Yankees Babe Ruth 1943 New York Yankees Spud Chandler 1958 Boston Red Sox Jackie Jensen 1969 Pittsburgh Pirates Matty Alou 1933 New York Yankees Tony Lazzeri 1944 Boston Red Sox Bobby Doerr 1958 Chicago Cubs Ernie Banks 1969 San Francisco Giants Willie McCovey 1933 Philadelphia Athletics Jimmie Foxx 1944 St. -

Marking Bronze Operation Decending Dragon

PRESORTED STANDARD US POSTAGE PAID PITTSBURGH, PA Two NorthShore Center PERMIT NO. 2705 Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania 15212-5851 VOL. DEC V 2010 OPERATION DECENDING DRAGON IPAD LAUNCH LATIN AMERICA BRONZE THE STORY OF A HUNGARIAN FREEDOM FIGHTER MARKING MATTHEWS BREWS MARKING RECIPE SPECIALA TRIBUTE FEATURE TO MAZ MARKING PRODUCTS CREMATION Matthews Brews Cremation Division’s a Marking Recipe for By Stephanie Kaminski Food Drive By Sandy Blinco The Boston Beer Company, America’s leading brewer of handcrafted, full- Beer Kegs flavored beers like Samuel Adams, recently purchased a custom designed laser Last month the employees of Matthews Cremation spontaneously system from Matthews Marking Products when the brewer was faced with the opened their hearts and their wallets to help those less fortunate. challenge of labeling its stainless steel kegs. Previously, a hand applied label was It might not have been the “holiday giving” that is most often done used for government-mandated information, but applying the label required at Thanksgiving, Christmas, or Easter, but it was a time of year when costly labor and materials, and there was the risk of the label detaching from the local families were in desperate need of assistance. In previous years, Cremation keg during the keg float cycle. There are strict government regulations requiring employees donated toys for the Loaves & Fishes Christmas Toy Drive, but this is affixing of the label. If the brewer is found not to meet these requirements, stiff the first time they have pulled together to give food to some of these same families. penalties are applied. Matthews Marking Products’ laser system addressed both Employees located the largest boxes they could find and filled them to the brim. -

2017 Information & Record Book

2017 INFORMATION & RECORD BOOK OWNERSHIP OF THE CLEVELAND INDIANS Paul J. Dolan John Sherman Owner/Chairman/Chief Executive Of¿ cer Vice Chairman The Dolan family's ownership of the Cleveland Indians enters its 18th season in 2017, while John Sherman was announced as Vice Chairman and minority ownership partner of the Paul Dolan begins his ¿ fth campaign as the primary control person of the franchise after Cleveland Indians on August 19, 2016. being formally approved by Major League Baseball on Jan. 10, 2013. Paul continues to A long-time entrepreneur and philanthropist, Sherman has been responsible for establishing serve as Chairman and Chief Executive Of¿ cer of the Indians, roles that he accepted prior two successful businesses in Kansas City, Missouri and has provided extensive charitable to the 2011 season. He began as Vice President, General Counsel of the Indians upon support throughout surrounding communities. joining the organization in 2000 and later served as the club's President from 2004-10. His ¿ rst startup, LPG Services Group, grew rapidly and merged with Dynegy (NYSE:DYN) Paul was born and raised in nearby Chardon, Ohio where he attended high school at in 1996. Sherman later founded Inergy L.P., which went public in 2001. He led Inergy Gilmour Academy in Gates Mills. He graduated with a B.A. degree from St. Lawrence through a period of tremendous growth, merging it with Crestwood Holdings in 2013, University in 1980 and received his Juris Doctorate from the University of Notre Dame’s and continues to serve on the board of [now] Crestwood Equity Partners (NYSE:CEQP). -

November 13, 2010 Prices Realized

SCP Auctions Prices Realized - November 13, 2010 Internet Auction www.scpauctions.com | +1 800 350.2273 Lot # Lot Title 1 C.1910 REACH TIN LITHO BASEBALL ADVERTISING DISPLAY SIGN $7,788 2 C.1910-20 ORIGINAL ARTWORK FOR FATIMA CIGARETTES ROUND ADVERTISING SIGN $317 3 1912 WORLD CHAMPION BOSTON RED SOX PHOTOGRAPHIC DISPLAY PIECE $1,050 4 1914 "TUXEDO TOBACCO" ADVERTISING POSTER FEATURING IMAGES OF MATHEWSON, LAJOIE, TINKER AND MCGRAW $288 5 1928 "CHAMPIONS OF AL SMITH" CAMPAIGN POSTER FEATURING BABE RUTH $2,339 6 SET OF (5) LUCKY STRIKE TROLLEY CARD ADVERTISING SIGNS INCLUDING LAZZERI, GROVE, HEILMANN AND THE WANER BROTHERS $5,800 7 EXTREMELY RARE 1928 HARRY HEILMANN LUCKY STRIKE CIGARETTES LARGE ADVERTISING BANNER $18,368 8 1930'S DIZZY DEAN ADVERTISING POSTER FOR "SATURDAY'S DAILY NEWS" $240 9 1930'S DUCKY MEDWICK "GRANGER PIPE TOBACCO" ADVERTISING SIGN $178 10 1930S D&M "OLD RELIABLE" BASEBALL GLOVE ADVERTISEMENTS (3) INCLUDING COLLINS, CRITZ AND FONSECA $1,090 11 1930'S REACH BASEBALL EQUIPMENT DIE-CUT ADVERTISING DISPLAY $425 12 BILL TERRY COUNTERTOP AD DISPLAY FOR TWENTY GRAND CIGARETTES SIGNED "TO BARRY" - EX-HALPER $290 13 1933 GOUDEY SPORT KINGS GUM AND BIG LEAGUE GUM PROMOTIONAL STORE DISPLAY $1,199 14 1933 GOUDEY WINDOW ADVERTISING SIGN WITH BABE RUTH $3,510 15 COMPREHENSIVE 1933 TATTOO ORBIT DISPLAY INCLUDING ORIGINAL ADVERTISING, PIN, WRAPPER AND MORE $1,320 16 C.1934 DIZZY AND DAFFY DEAN BEECH-NUT ADVERTISING POSTER $2,836 17 DIZZY DEAN 1930'S "GRAPE NUTS" DIE-CUT ADVERTISING DISPLAY $1,024 18 PAIR OF 1934 BABE RUTH QUAKER -

Special Ticket Promotion for All State of Indiana Employees to See Irt’S Going Solo Festival! All Tickets Only $15

& SPECIAL TICKET PROMOTION FOR ALL STATE OF INDIANA EMPLOYEES TO SEE IRT’S GOING SOLO FESTIVAL! ALL TICKETS ONLY $15 IRT’s Going Solo festival of three intimate one-actor Sept. 20th—Oct. 23rd plays returns for its third year of audience acclaim. A highlight this season will be an original work by IRT playwright-in-residence James Still. An added ad- vantage for IRT subscribers: you can enjoy your as- signed performance and then choose a weeknight per- formance of either of the other two plays in the series. Sept. 27th—Oct. 23rd Before Rachel Ray, before Julia Child, there was James Beard, the first TV chef! He brought fine cooking to the small screen in 1946 and helped establish an American cuisine. His message of good food, honestly prepared with fresh, wholesome ingredients, made him America’s first foodie. Come meet the man described as “the face Robert Neal and belly of American gastronomy.” For the Greatest Generation, baseball was the na- tion’s pastime. Every team had its heroes, and the Sept. 23rd—Oct. 23rd New York Yankees had Yogi Berra, the finest catcher the game has ever known. Yogi was famous for his way with words (“It ain’t over till it’s over”) and for his even temperament—but also for his 14-year feud with Yankees’ owner George Steinbrenner. Yogi Mark Goetzinger looks back at the life experiences that led him to return to Yankee Stadium, offering his unique view of baseball, relationships, and life! Sept. 20th—Oct. 15th Cathy’s brother calls home every year on his birthday but not this year. -

Jews and Baseball: an American Love Story

Mishkan Film Screening Fund Raiser Jews and Baseball: An American Love Story Sunday, April 10 at 7:00pm Hiway Theater, 212 York Road, Jenkintown, PA Following the movie, there will be the opportunity to meet and talk with Peter Miller, the director of the movie, and Rabbi Rebecca Alpert, who is an important voice in the movie. Enjoy this fun evening and contribute to Mishkan Shalom! Synopsis Ticket Prices & Payment Options: This film is so much more than a 1st Base: $18 2nd Base: $36 3rd Base: $54 documentary about Jews, sports Home Run: $72 Rookies (Students): $10 Other: $_____ and baseball. This is a story of Help us plan. Kindly add $5 per ticket to registrations immigration, assimilation, bigotry, received after Monday, April 4. heroism, the passing on of traditions, and the shattering of By Check: Payable to Mishkan Shalom c/o 4101 Freeland stereotypes. Avenue, Philadelphia, PA 19128. Write Jews and Baseball in the subject line with the number of seats you are reserving. The story is brought to life through Guest names helpful. Dustin Hoffman’s narration and interviews with dozens of Online: http://mishkan.org/donations/donation. Direct passionate and articulate fans, donation to General Fund, and specify Jews and Baseball writers, executives, and especially in the Notes field along with the number of seats you are players, including Al Rosen, Kevin reserving. Guests names helpful. Youkilis, Shawn Green, Bob Feller, Yogi Berra, and a rare interview with the Hall of Fame pitcher Awards & Testimonials Sandy Koufax. — Best-Editing Award Breckenridge Film Festival Fans including Ron Howard and — West Coast Premiere San Francisco Jewish Film Festival Larry King connect the stories of — International Premiere Jerusalem International Film Festival baseball to their own lives and to — “Irresistible to baseball fans, Hebraic or otherwise.” the turbulent history of the last -Time Out New York century. -

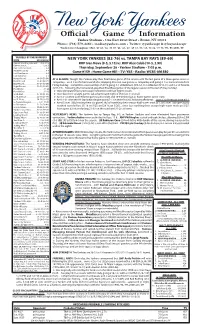

Official Game Information

Official Game Information Yankee Stadium • One East 161st Street • Bronx, NY 10451 Phone: (718) 579-4460 • [email protected] • Twitter: @yankeespr & @losyankeespr World Series Champions: 1923, ’27-28, ’32, ’36-39, ’41, ’43, ’47, ’49-53, ’56, ’58, ’61-62, ’77-78, ’96, ’98-2000, ’09 YANKEES BY THE NUMBERS NOTE 2013 (2012) NEW YORK YANKEES (82-76) vs. TAMPA BAY RAYS (89-69) Current Standing in AL East: . T3rd, -13 .5 RHP Ivan Nova (9-5, 3.13) vs. RHP Alex Cobb (10-3, 2.90) Current Streak: . .. Lost 3 Current Homestand: . 2-3 Thursday, September 26 • Yankee Stadium • 7:05 p.m. Recent Road Trip: . 4-6 Last Five Games: . 2-3 Game #159 • Home Game #81 • TV: YES • Radio: WCBS-AM 880 Last 10 Games: . 3-7 Home Record: . 46-34 (51-30) AT A GLANCE: Tonight the Yankees play their final home game of the season with the last game of a three-game series vs . Road Record: . .36-42 (44-37) Tampa Bay… are 2-3 on the homestand after dropping their first two games vs . Tampa Bay and going 2-1 vs . San Francisco from Day Record: . .. 31-24 (32-20) Night Record: . 51-52 (63-47) Friday-Sunday… completed a 4-6 road trip on 9/19 going 3-1 at Baltimore (9/9-12), 0-3 at Boston (9/13-15) and 1-2 at Toronto Pre-All-Star . 51-44 (9/17-19)… following this homestand, play their final three games of the regular season at Houston (Friday-Sunday) . Post-All-Star . -

Xauitr Uuiutrsity. Ntws

Xavier University Exhibit All Xavier Student Newspapers Xavier Student Newspapers 1947-05-09 Xavier University Newswire Xavier University (Cincinnati, Ohio) Follow this and additional works at: https://www.exhibit.xavier.edu/student_newspaper Recommended Citation Xavier University (Cincinnati, Ohio), "Xavier University Newswire" (1947). All Xavier Student Newspapers. 1793. https://www.exhibit.xavier.edu/student_newspaper/1793 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Xavier Student Newspapers at Exhibit. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Xavier Student Newspapers by an authorized administrator of Exhibit. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Xauitr Uuiutrsity .. Ntws ~enior Ball. May 16 f A Weekly Newspaper By Students From The Evanston, I B T" k N I I. _ . Downtown, And Milford Campuses. .. ay lC ets ow . VOLUME XXXI CINCINNATI, OHIO, FRIDAY, MAY 9, 1947 NO. 22 ·Gibson, May 29 Hotly Contested Election Ends Maringer New A-nnual Press I s . v· F ' . Head Of 'X' Dinner Scene n weeping ictory or Eight Music Dept. Xavier University, in a bid to ne'!,h~o F~~s~i~e~n~~ ~:es:ta~i~; New Campus_ Representatives build a versatile, full-scale mus the Xavier U11iversity News, will ical organization, has appointed Gilbert Maringer Head of the be held Thursday evening, May After three days of heavy balloting in which more than 900 students participated, 29 at 6: 00 p.m. in the Hotel newly organized Music Depart votes have been counted, and according to the XU Student Counsellor, the Rev. Frank ment. Mr. Maringer, /formerly Gibson Ballroom it was an Dietz, S.J., the following nominees were successful in their campaigns. -

National Pastime a REVIEW of BASEBALL HISTORY

THE National Pastime A REVIEW OF BASEBALL HISTORY CONTENTS The Chicago Cubs' College of Coaches Richard J. Puerzer ................. 3 Dizzy Dean, Brownie for a Day Ronnie Joyner. .................. .. 18 The '62 Mets Keith Olbermann ................ .. 23 Professional Baseball and Football Brian McKenna. ................ •.. 26 Wallace Goldsmith, Sports Cartoonist '.' . Ed Brackett ..................... .. 33 About the Boston Pilgrims Bill Nowlin. ..................... .. 40 Danny Gardella and the Reserve Clause David Mandell, ,................. .. 41 Bringing Home the Bacon Jacob Pomrenke ................. .. 45 "Why, They'll Bet on a Foul Ball" Warren Corbett. ................. .. 54 Clemente's Entry into Organized Baseball Stew Thornley. ................. 61 The Winning Team Rob Edelman. ................... .. 72 Fascinating Aspects About Detroit Tiger Uniform Numbers Herm Krabbenhoft. .............. .. 77 Crossing Red River: Spring Training in Texas Frank Jackson ................... .. 85 The Windowbreakers: The 1947 Giants Steve Treder. .................... .. 92 Marathon Men: Rube and Cy Go the Distance Dan O'Brien .................... .. 95 I'm a Faster Man Than You Are, Heinie Zim Richard A. Smiley. ............... .. 97 Twilight at Ebbets Field Rory Costello 104 Was Roy Cullenbine a Better Batter than Joe DiMaggio? Walter Dunn Tucker 110 The 1945 All-Star Game Bill Nowlin 111 The First Unknown Soldier Bob Bailey 115 This Is Your Sport on Cocaine Steve Beitler 119 Sound BITES Darryl Brock 123 Death in the Ohio State League Craig -

Yogi Berra Trivia

YOGI BERRA TRIVIA • What city was Yogi Berra born? a ) San Luis Obispo, CA b) St. Lawrence, NY c) St. Louis, MO d) St. Petersburg, FL • Who was Yogi’s best friend growing up? a) Joe Torre b) Joe Garagiola c) Joe Pepitone d) Shoeless Joe Jackson • Who was one of Yogi’s first Yankee roommates and later became a doctor? a) Doc Medich b) Jerry (“Oh, Doctor”) Coleman c) Doc Cramer d) Bobby Brown • When Yogi appeared in the soap opera General Hospital in 1962, who did he play? a) Brain surgeon Dr. Lawrence P. Berra b) Cardiologist Dr. Pepper c) General physician Dr. Yogi Berra d) Dr. Kildare’s cousin • The cartoon character Yogi Bear was created in 1958 and largely inspired by Yogi Berra. a) True, their names and genial personalities can’t be a coincidence. b) False, the creators Hanna-Barbera somehow never heard of Yogi Berra. c) Hanna-Barbera denied that umpire Augie Donatelli inspired the character Augie Doggie. d) Hanna-Barbera seriously considered a cartoon character named Bear Bryant. • In Yogi’s first season (1947), his salary was $5,000. What did he earn for winning the World Series that year? a) A swell lunch with the owners. b) $5,000 winner’s share. c) A trip to the future home of Disney World. d) A gold watch from one of the team sponsors • When Yogi won his first Most Valuable Player Award in 1951, what did he do in the offseason? a) Took a two-month cruise around the world. b) Opened a chain of America’s first frozen yogurt stores. -

State to Get 460 Acres of Sandy Hook for Park

Distribution Weather Today A few ilwirtrt ttday, Ufa M. MMKly Mr aad cotter tenigtit aad 18,300 fcnMMwr. Urn tonight, «; hlfb tomorrow, M'I. ,, Dial SH (-0010 limed d»to, MonSiy ttiouili TrMay. iKond Clui P<»U» RED BANK, N. J., THURSDAY, OCTOBER 26, 1961 7c PER COPY PAGE ONE VOL. 84, NO. 86 Pild tt R«d Bulk ud, »t Addltlonll liUUnf OtflCM. Want Night Racing r, State to Get 460 Acres Freehold Twp. Asks Legislature to Act FREEHOLD TOWflSHIP -The 537, which is adjacent to the Wagner and Albert McCormick Township Committee last night raceway's present location. abstaining. adopted a resolution asking the At that time, plans to build a Freehold Raceway is the slate's ittte Legislature to permit night new racing oval in the township only harness track. Copies of the harneis racing in New Jersey. were announced. resolution were sent to all county Last spring, the Freehold Race- The resolution was approved by legislators and their opponents in Of Sandy Hook for Park way purchased a 90-acre tract for three members of the committee, the Nov. 7 election. $300,000 from Walter Lolt on Rt. with Committeemen Norman Committeeman McCormick said he abstained from voting be- ause he wanted the measure tabled until the next meeting (the Udall Sees Lease Court Issues New ight following election) in order that it might be given further consideration and to "get the feeling of our constitutents on the OK Within Week Ruling on'Conf lief matter." Mr. McCormick added that he NEWARK (AP)—Within a week the Defense De- UNION BEACH - The state a conference session, had found ould see no harm in delaying the ; partment will approve the leasing of 460 acres of resolution. -

Sport-Scan Daily Brief

SPORT-SCAN DAILY BRIEF NHL 8/14/2020 Anaheim Ducks Chicago Blackhawks 1190979 Canadiens coach Claude Julien taken to hospital after 1191006 Blackhawks down 2-0 in series against Golden Knights experiencing chest pains after a 4-3 overtime loss in Game 2 1190980 J-S Giguere recalls Mighty Ducks’ ‘nightmare’ 5 OT win in 1191007 3 things to watch for in Game 2 of the Blackhawks-Golden 2003 playoffs Knights series, including a Patrick Kane-Jonathan Toe 1191008 Blackhawks notebook: Jeremy Colliton scratches Adam Arizona Coyotes Boqvist, shuffles lines in Game 2 loss 1190981 After poor showing in Game 1, Coyotes' offense hope for 1191009 Blackhawks’ strong effort confined to 2nd period as Schmaltz's return Golden Knights win Game 2 in overtime 1190982 Ian Cole Diary, Part 2: On winning Game 1, playing 1191010 Eddie Olczyk describes life in broadcasting bubble during back-to-backs and Phil Kessel Stanley Cup playoffs 1191011 Blackhawks' best effort not enough in Game 2 Boston Bruins 1191012 Blackhawks' Patrick Kane found his postseason game, but 1190983 Bruins goaltender Tuukka Rask on playoff hockey in 2020: is it too late? ‘It feels dull at times’ 1191013 Blackhawks must 'regroup fast' after falling behind 2-0 1190984 Dougie Hamilton roofs winner as Carolina evens series against Golden Knights with Bruins 1191014 Blackhawks' Patrick Kane and Corey Crawford bounce 1190985 David Pastrnak deemed unfit to participate, out for Game back, but Hawks drop Game 2 2 1191015 Blackhawks make lineup changes for Game 2 vs. Vegas 1190986 Former Bruins coach Claude Julien hospitalized with chest Golden Knights pains 1191016 Robin Lehner tweets hilarious cartoon ahead of Game 2 1190987 Bruins drop Game 2 to Hurricanes against Blackhawks 1190988 Hurricanes coach Brind’Amour ‘moving on’ after fined by 1191017 How Blackhawks will try to generate more offense in NHL Game 2 vs.