Abstract for Interview with Edward Baugh, 30 January 2018 Edward Baugh Is an Internationally Acclaimed Poet and Scholar

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

We Make It Easier for You to Sell

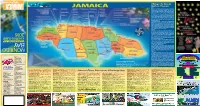

We Make it Easier For You to Sell Travel Agent Reference Guide TABLE OF CONTENTS ITEM PAGE ITEM PAGE Accommodations .................. 11-18 Hotels & Facilities .................. 11-18 Air Service – Charter & Scheduled ....... 6-7 Houses of Worship ................... .19 Animals (entry of) ..................... .1 Jamaica Tourist Board Offices . .Back Cover Apartment Accommodations ........... .19 Kingston ............................ .3 Airports............................. .1 Land, History and the People ............ .2 Attractions........................ 20-21 Latitude & Longitude.................. .25 Banking............................. .1 Major Cities......................... 3-5 Car Rental Companies ................. .8 Map............................. 12-13 Charter Air Service ................... 6-7 Marriage, General Information .......... .19 Churches .......................... .19 Medical Facilities ..................... .1 Climate ............................. .1 Meet The People...................... .1 Clothing ............................ .1 Mileage Chart ....................... .25 Communications...................... .1 Montego Bay......................... .3 Computer Access Code ................ 6 Montego Bay Convention Center . .5 Credit Cards ......................... .1 Museums .......................... .24 Cruise Ships ......................... .7 National Symbols .................... .18 Currency............................ .1 Negril .............................. .5 Customs ............................ .1 Ocho -

Destination Jamaica

© Lonely Planet Publications 12 Destination Jamaica Despite its location almost smack in the center of the Caribbean Sea, the island of Jamaica doesn’t blend in easily with the rest of the Caribbean archipelago. To be sure, it boasts the same addictive sun rays, sugary sands and pampered resort-life as most of the other islands, but it is also set apart historically and culturally. Nowhere else in the Caribbean is the connection to Africa as keenly felt. FAST FACTS Kingston was the major nexus in the New World for the barbaric triangular Population: 2,780,200 trade that brought slaves from Africa and carried sugar and rum to Europe, Area: 10,992 sq km and the Maroons (runaways who took to the hills of Cockpit Country and the Blue Mountains) safeguarded many of the African traditions – and Length of coastline: introduced jerk seasoning to Jamaica’s singular cuisine. St Ann’s Bay’s 1022km Marcus Garvey founded the back-to-Africa movement of the 1910s and ’20s; GDP (per head): US$4600 Rastafarianism took up the call a decade later, and reggae furnished the beat Inflation: 5.8% in the 1960s and ’70s. Little wonder many Jamaicans claim a stronger affinity for Africa than for neighboring Caribbean islands. Unemployment: 11.3% And less wonder that today’s visitors will appreciate their trip to Jamaica Average annual rainfall: all the more if they embrace the island’s unique character. In addition to 78in the inherent ‘African-ness’ of its population, Jamaica boasts the world’s Number of orchid species best coffee, world-class reefs for diving, offbeat bush-medicine hiking tours, found only on the island: congenial fishing villages, pristine waterfalls, cosmopolitan cities, wetlands 73 (there are more than harboring endangered crocodiles and manatees, unforgettable sunsets – in 200 overall) short, enough variety to comprise many utterly distinct vacations. -

Caribbean Theatre: a PostColonial Story

CARIBBEAN THEATRE: A POSTCOLONIAL STORY Edward Baugh I am going to speak about Caribbean theatre and drama in English, which are also called West Indian theatre and West Indian drama. The story is one of how theatre in the English‐speaking Caribbean developed out of a colonial situation, to cater more and more relevantly to native Caribbean society, and how that change of focus inevitably brought with it the writing of plays that address Caribbean concerns, and do that so well that they can command admiring attention from audiences outside the Caribbean. I shall begin by taking up Ms [Chihoko] Matsuda’s suggestion that I say something about my own involvement in theatre, which happened a long time ago. It occurs to me now that my story may help to illustrate how Caribbean theatre has changed over the years and, in the process, involved the emergence of Caribbean drama. Theatre was my hobby from early, and I was actively involved in it from the mid‐Nineteen Fifties until the early Nineteen Seventies. It was never likely to be more than a hobby. There has never been a professional theatre in the Caribbean, from which one could make a living, so the thought never entered my mind. And when I stopped being actively involved in theatre, forty years ago, it was because the demands of my job, coinciding with the demands of raising a family, severely curtailed the time I had for stage work, especially for rehearsals. When I was actively involved in theatre, it was mainly as an actor, although I also did some Baugh playing Polonius in Hamlet (1967) ― 3 ― directing. -

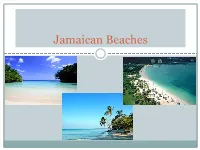

Jamaican Beaches Introduction

Jamaican Beaches Introduction Visiting the beach is a traditional recreational activity for many Jamaicans. With an increasing population, there is a great demand for the use of beaches. However, many of the public beaches are of poor quality, lack proper facilities, and face the problem of fishermen encroaching. Over the years some of these natural resources are on the verge of destruction because of the inadvertent and/or direct intentions of organizations and individuals. One such threat to the preservation of beaches is pollution. To have healthy environmentally friendly beaches in our Island we must unite to prevent pollution. This display gives an overview of some beaches in Jamaica and existing threats. It also examines the Kingston Harbour and how we can protect these natural resources. Jamaica is blessed with many beautiful beaches in the different parishes; the most popular are located in Westmoreland (Negril), St. Ann, St. James, and St. Catherine (Portmore). Some of the more popular beaches in the parishes: Kingston and St. Andrew Harbour Head Gunboat Copacabana Ocean Lake St. Thomas Lyssons Rozelle South Haven Mezzgar’s Run Retreat Prospect Rocky Point Portland Innis Bay Long Bay Boston Winnifred Blue Hole Hope Bay St. Mary Rio Nuevo Rockmore Murdock St. Ann Roxborough Priory Salem Sailor’s Hole Cardiff Hall Discovery Bay Dunn’s River Beach Trelawny Rio Bueno Braco Silver Sands Flamingo Half Moon Bay St. James Greenwood RoseHall Coral Gardens Ironshore Doctor’s Cave Hanover Tryall Lance’s Bay Bull Bay Westmoreland Little Bay Whitehouse Fonthill Bluefield St. Catherine Port Henderson Hellshire Fort Clarence St. Elizabeth Galleon Hodges Fort Charles Calabash Bay Great Bay Manchester Calabash Bay Hudson Bay Canoe Valley Clarendon Barnswell Dale Jackson Bay The following is a brief summary of some of our beautiful beaches: Walter Fletcher Beach Before 1975 it was an open stretch of public beach in Montego Bay with no landscaping and privacy; it was visible from the main road. -

We Make It Easier for You to Sell

We Make it Easier For You to Sell Travel Agent Reference Guide TABLE OF CONTENTS ITEM PAGE ITEM PAGE Accommodations .................. 11-18 Hotels & Facilities .................. 11-18 Air Service – Charter & Scheduled ....... 6-7 Houses of Worship ................... .19 Animals (entry of) ..................... .1 Jamaica Tourist Board Offices . .Back Cover Apartment Accommodations ........... .19 Kingston ............................ .3 Airports............................. .1 Land, History and the People ............ .2 Attractions........................ 20-21 Latitude & Longitude.................. .25 Banking............................. .1 Major Cities......................... 3-5 Car Rental Companies ................. .8 Map............................. 12-13 Charter Air Service ................... 6-7 Marriage, General Information .......... .19 Churches .......................... .19 Medical Facilities ..................... .1 Climate ............................. .1 Meet The People...................... .1 Clothing ............................ .1 Mileage Chart ....................... .25 Communications...................... .1 Montego Bay......................... .3 Computer Access Code ................ 6 Montego Bay Convention Center . .5 Credit Cards ......................... .1 Museums .......................... .24 Cruise Ships ......................... .7 National Symbols .................... .18 Currency............................ .1 Negril .............................. .5 Customs ............................ .1 Ocho -

Vol 24 / No. 1 / April 2016 Volume 24 Number 1 April 2016

1 Vol 24 / No. 1 / April 2016 Volume 24 Number 1 April 2016 Published by the discipline of Literatures in English, University of the West Indies CREDITS Original image: High tide at the cave, 2016 by Lee Ann Sanowar Anu Lakhan (copy editor) Nadia Huggins (graphic designer) JWIL is published with the financial support of the Departments of Literatures in English of The University of the West Indies Enquiries should be sent to THE EDITORS Journal of West Indian Literature Department of Literatures in English, UWI Mona Kingston 7, JAMAICA, W.I. Tel. (876) 927-2217; Fax (876) 970-4232 e-mail: [email protected] OR Ms. Angela Trotman Department of Language, Linguistics and Literature Faculty of Humanities, UWI Cave Hill Campus P.O. Box 64, Bridgetown, BARBADOS, W.I. e-mail: [email protected] SUBSCRIPTION RATE US$20 per annum (two issues) or US$10 per issue Copyright © 2016 Journal of West Indian Literature ISSN (online): 2414-3030 EDITORIAL COMMITTEE Evelyn O’Callaghan (Editor in Chief) Michael A. Bucknor (Senior Editor) Glyne Griffith Rachel L. Mordecai Lisa Outar Ian Strachan BOOK REVIEW EDITOR Antonia MacDonald EDITORIAL BOARD Edward Baugh Victor Chang Alison Donnell Mark McWatt Maureen Warner-Lewis EDITORIAL ADVISORY BOARD Laurence A. Breiner Rhonda Cobham-Sander Daniel Coleman Anne Collett Raphael Dalleo Denise deCaires Narain Curdella Forbes Aaron Kamugisha Geraldine Skeete Faith Smith Emily Taylor THE JOURNAL OF WEST INDIAN LITERATURE has been published twice-yearly by the Departments of Literatures in English of the University of the West Indies since October 1986. Edited by full time academics and with minimal funding or institutional support, the Journal originated at the same time as the first annual conference on West Indian Literature, the brainchild of Edward Baugh, Mervyn Morris and Mark McWatt. -

MONTEGO Identified

Things To Know Before You Go JAMAICA DO’S: At the airport: Use authorised pick up points for rented cars, taxis and buses. Use authorised transportation services and representatives. Transportation providers licensed by the Jamaica Tourist Board (JTB) bear a JTB sticker on the wind- screen. If you rent a car: Use car rental companies licensed by the Jamaica Tourist Board. Get directions before leaving the airport and rely on your map during your journey. Lock your car doors. Go to a service station or other well-lit public place if, while driving at night, you become lost or require as- sistance. Check your vehicle before heading out on the road each day. If problems develop, stop at the nearest service station and call to advise your car rental company. They will be happy to assist you. On the road: Remember to drive on the left. Observe posted speed limits and traffic signs. Use your seat belts. Always use your horn when approaching a blind corner on our nar- row and winding country roads. Try to travel with a group at night. While shopping: Carry your wallet discreetly. Use credit cards or traveller’s cheques for major purchases, if possible. In your hotel: Store valuables in a safety deposit box. Report suspicious-looking persons or activity to the front desk per- sonnel. Always lock your doors securely. DONT’S: At the airport: Do not Pack valuables (cash, jewellery, etc.) in 6 1 0 2 your luggage. Leave baggage unattended. If you rent a car: Do not Leave your engine running unattended. -

History of Portland

History of Portland The Parish of Portland is located at the north eastern tip of Jamaica and is to the north of St. Thomas and to the east of St. Mary. Portland is approximately 814 square kilometres and apart from the beautiful scenery which Portland boasts, the parish also comprises mountains that are a huge fortress, rugged, steep, and densely forested. Port Antonio and town of Titchfield. (Portland) The Blue Mountain range, Jamaica highest mountain falls in this parish. What we know today as the parish of Portland is the amalgamation of the parishes of St. George and a portion of St. Thomas. Portland has a very intriguing history. The original parish of Portland was created in 1723 by order of the then Governor, Duke of Portland, and also named in his honour. Port Antonio Port Antonio, the capital of Portland is considered a very old name and has been rendered numerous times. On an early map by the Spaniards, it is referred to as Pto de Anton, while a later one refers to Puerto de San Antonio. As early as 1582, the Abot Francisco, Marquis de Villa Lobos, mentions it in a letter to Phillip II. It was, however, not until 1685 that the name, Port Antonio was mentioned. Earlier on Portland was not always as large as it is today. When the parish was formed in 1723, it did not include the Buff Bay area, which was then part of St. George. Long Bay or Manchioneal were also not included. For many years there were disagreements between St. -

S Port Antonio and Ocho Rios by Lee Foster

Jamaica’s Port Antonio and Ocho Rios by Lee Foster The Jamaica of my experience proved to be an intriguing but challenging destination to recommend. I looked at old Port Antonio, where tourism began in Jamaica a hundred years ago. After that immersion, I visited the more modern Ocho Rios, where the newer phase of planned all-inclusive resort tourism greets the traveler. In this article, I compare these two faces of Jamaica today. The Jamaica I encountered was a Caribbean island with dependable warmth to thaw out wind-chilled northerners, with a reportedly glorious sun (even though it rained a little during my November trip), and with some lovely cream sand beaches (such as at my Dragon Bay Hotel in Port Antonio or Renaissance Jamaica Grande Resort in Ocho Rios). Port Antonio After flying into Kingston, I was driven across the mountains to Port Antonio. Be sure to have your hotel send a van to do this drive or get a local air shuttle from Kingston to Port Antonio or to Ocho Rios. The winding, potholed roads are challenging, even if you are skilled at driving on the left side of the road. Palatial villas of the rich in the hills above Kingston contrast dramatically with the grinding poverty of the countryside. If you are bothered by poverty, this island, beyond the perimeters of the all-inclusive resort, will disturb you. I admired some of the creative and energetic young Jamaicans, such as those who administer Mocking Bird Hill Hotel in Port Antonio, for trying to revitalize the area with an eco-tourism emphasis. -

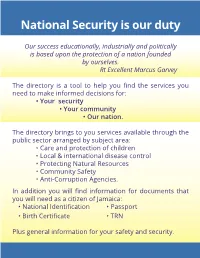

Resource Directory Is Intended As a General Reference Source

National Security is our duty Our success educationally, industrially and politically is based upon the protection of a nation founded by ourselves. Rt Excellent Marcus Garvey The directory is a tool to help you find the services you need to make informed decisions for: • Your security • Your community • Our nation. The directory brings to you services available through the public sector arranged by subject area: • Care and protection of children • Local & international disease control • Protecting Natural Resources • Community Safety • Anti-Corruption Agencies. In addition you will find information for documents that you will need as a citizen of Jamaica: • National Identification • Passport • Birth Certificate • TRN Plus general information for your safety and security. The directory belongs to Name: My local police station Tel: My police community officer Tel: My local fire brigade Tel: DISCLAIMER The information available in this resource directory is intended as a general reference source. It is made available on the understanding that the National Security Policy Coordination Unit (NSPCU) is not engaged in rendering professional advice on any matter that is listed in this publication. Users of this directory are guided to carefully evaluate the information and get appropriate professional advice relevant to his or her particular circumstances. The NSPCU has made every attempt to ensure the accuracy and reliability of the information that is published in this resource directory. This includes subject areas of ministries, departments and agencies (MDAs) names of MDAs, website urls, telephone numbers, email addresses and street addresses. The information can and will change over time by the organisations listed in the publication and users are encouraged to check with the agencies that are listed for the most up-to-date information. -

DRM Enforcement Measures Order 2021

JAN. 15, 2021] PROCLAMATIONS, RULES AND REGULATIONS 1 THE JAMAICA GAZETTE SUPPLEMENT PROCLAMATIONS, RULES AND REGULATIONS 1 Vol. CXLIV FRIDAY, JANUARY 15, 2021 No. 1 No. 1 THE DISASTER RISK MANAGEMENT ACT THE DISASTER RISK MANAGEMENT (ENFORCEMENT MEASURES) ORDER, 2021 WHEREAS the Minister responsible for disaster preparedness and emergency management has given written notice to the Prime Minister that Jamaica appears to be threatened with or affected by the SARS–CoV-2 (Coronavirus COVID-19), and that measures apart from or in addition to those specifically provided for in the Disaster Risk Management Act should be taken promptly: AND WHEREAS on March 13, 2020, the Prime Minister by Order declared the whole of Jamaica to be a disaster area: NOW THEREFORE: In exercise of the powers conferred upon the Prime Minister by section 26(2) of the Disaster Risk Management Act, the following Order is hereby made:— Citation. 1. This Order may be cited as the Disaster Risk Management (Enforcement Measures) Order, 2021, and shall take effect on the 15th day of January, 2021. 2 PROCLAMATIONS, RULES AND REGULATIONS [JAN. 15, 2021 Enforcement. 2. The measures set out in this Order are directed to be enforced,in accordance with sections 26(5) to (7) and 52 of the Act, for removing or otherwise guarding against or mitigating the threat, or effects, of the SARS – CoV-2 (Coronavirus COVID-19) and the possible consequences thereof. Requirements 3.—(1) A person who, during the period January 15, 2021, to April 15, for entry to 2021, seeks to enter Jamaica, shall— Jamaica. (a) if the person is ordinarily resident in Jamaica, complete,through the website https://jamcovid19.moh.gov.jm/, the relevant application for entry; or (b) if the person is not ordinarily resident in Jamaica, (i) complete, through the website https:// www.visitjamaica.com, the relevant application for entry; and (ii) comply with all applicable provisions of the Immigration Restriction (Commonwealth Citizens) Act and the Aliens Act. -

Verbatim Minutes Bull Bay2017.Pdf

1 VERBATIM NOTES OF THE PUBLIC PRESENENTATION ON THE ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT ASSESSMENT FOR THE PROPOSED ROAD IMPROVEMENT PROJECT FROM HARBOUR VIEW, KINGSTON TO YALLAHS BRIDGE, ST. THOMAS (SECTION 1A OF THE SOUTHERN HIGHWAY IMPROVEMENT PROJECT (SCHIP)), HELD AT BULL BAY ON WEDNESDAY, NOVEMBER 22,2017 COMMENCING AT 5:46 P.M. PRESENT WERE: The Panel Mr. M. Hutchinson - Chairman Mr. Reynolds Mr. S. Shaw Mr. W. McCarge Mr. A. Marshall Ms. R. Lawson Mr. L. Barrett Dr. C. Campbell Mr. G. Bennett Participants Deacon A. Williams Ms. S. Cole Mr. N. Elthan Ms. P. Henry MR. P. Hudson Mr. B. Byfield Mrs. J. Holness Ms. S. McFarlane Mr. D. Senior Ms. D. Abrahams . S. Bohaven Ms. C. Wilmot Ms. M. Ottey Mr. P. Hibbert Mr. P. Espeut Mr. M. Clarke AND OTHER RESIDENTS 2 Mr. Shaw: We are going to go start the meeting. I was hoping and we are still hoping that the Member of Parliament Mrs. Juliette Holness will be present, not sure why she is not here yet, but we hope that she will join us before the meeting ends. Now, this meeting this afternoon going into evening, has to do with the Southern Coastal Highway Improvement Project. This project having been conceptualized by the Government of Jamaica, speaks to us improving the road from Harbour View to Yallahs, Yallahs to Morant Bay, Morant Bay to Port Antonio and Morant Bay to Cedar Valley. Now as part of the overall programme of works, the Government also intends to do work on the East/West Highway, 3 this is the road that will take you from Mandela heading to May Pen.