FMA Visit to Georgia 2019

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

December 2020 Contract Pipeline

OFFICIAL USE No Country DTM Project title and Portfolio Contract title Type of contract Procurement method Year Number 1 2021 Albania 48466 Albanian Railways SupervisionRehabilitation Contract of Tirana-Durres for Rehabilitation line and ofconstruction the Durres of- Tirana a new Railwaylink to TIA Line and construction of a New Railway Line to Tirana International Works Open 2 Albania 48466 Albanian Railways Airport Consultancy Competitive Selection 2021 3 Albania 48466 Albanian Railways Asset Management Plan and Track Access Charges Consultancy Competitive Selection 2021 4 Albania 49351 Albania Infrastructure and tourism enabling Albania: Tourism-led Model For Local Economic Development Consultancy Competitive Selection 2021 5 Albania 49351 Albania Infrastructure and tourism enabling Infrastructure and Tourism Enabling Programme: Gender and Economic Inclusion Programme Manager Consultancy Competitive Selection 2021 6 Albania 50123 Regional and Local Roads Connectivity Rehabilitation of Vlore - Orikum Road (10.6 km) Works Open 2022 7 Albania 50123 Regional and Local Roads Connectivity Upgrade of Zgosth - Ura e Cerenecit road Section (47.1km) Works Open 2022 8 Albania 50123 Regional and Local Roads Connectivity Works supervision Consultancy Competitive Selection 2021 9 Albania 50123 Regional and Local Roads Connectivity PIU support Consultancy Competitive Selection 2021 10 Albania 51908 Kesh Floating PV Project Design, build and operation of the floating photovoltaic plant located on Vau i Dejës HPP Lake Works Open 2021 11 Albania 51908 -

Law of Georgia Tax Code of Georgia

LAW OF GEORGIA TAX CODE OF GEORGIA SECTION I GENERAL PROVISIONS Chapter I - Georgian Tax System Article 1 - Scope of regulation In accordance with the Constitution of Georgia, this Code sets forth the general principles of formation and operation of the tax system of Georgia, governs the legal relations involved in the movement of passengers, goods and vehicles across the customs border of Georgia, determines the legal status of persons, tax payers and competent authorities involved in legal relations, determines the types of tax offences, the liability for violating the tax legislation of Georgia, the terms and conditions for appealing wrongful acts of competent authorities and of their officials, lays down procedures for settling tax disputes, and governs the legal relations connected with the fulfilment of tax liabilities. Law of Georgia No 5942 of 27 March 2012 - website, 12.4.2012 Article 2 - Tax legislation of Georgia 1. The tax legislation of Georgia comprises the Constitution of Georgia, international treaties and agreements, this Code and subordinate normative acts adopted in compliance with them. 2. The tax legislation of Georgia in effect at the moment when tax liability arises shall be used for taxation. 3. The Government of Georgia or the Minister for Finance of Georgia shall adopt/issue subordinate normative acts for enforcing this Code. 4. (Deleted - No 1886, 26.12.2013) 5. To enforce the tax legislation of Georgia, the head of the Legal Entity under Public Law (LEPL) within the Ministry for Finance of Georgia - the Revenue Service (‘the Revenue Service’) shall issue orders, internal instructions and guidelines on application of the tax legislation of Georgia by tax authorities. -

News Digest on Georgia

NEWS DIGEST ON GEORGIA May 13-15 Compiled by: Aleksandre Davitashvili Date: May 16, 2019 Foreign Affairs 1. Georgia negotiating with Germany, France, Poland, Israel on legal employment Georgia is negotiating with three EU member states, Germany, France and Poland to allow for the legal employment of Georgians in those countries, as well as with Israel, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Georgia reports. An agreement has already been achieved with France. ―Legal employment of Georgians is one of the priorities for the ministry of Foreign Affairs, as such deals will decrease the number of illegal migrants and boost the qualification of Georgian nationals,‖ the Foreign Ministry says. A pilot project is underway with Poland, with up to 45 Georgian citizens legally employed, the ministry says (Agenda.ge, May 13, 2019). 2. Georgia elected as United Nations Statistical Commission member for 2020-2023 Georgia was unanimously elected as a member of the United Nations Statistical Commission (UNSC) for a period of four years, announces the National Statistics Office of Georgia (Geostat). The membership mandate will span from 2020-2023. A total of eight new members of the UNSC were elected for the same period on May 7 in New York at the meeting of the United Nations Economic and Social Council (ECOSOC) (Agenda.ge, May 14, 2019). 3. President of European Commission Tusk: 10 years on there is more Armenia, Azerbaijan, Belarus, Georgia, Moldova, Ukraine in EU President of the European Commission Donald Tusk stated on the 10th anniversary of the EU‘s Eastern Partnership format that there is more Armenia, Azerbaijan, Belarus, Georgia, Moldova and Ukraine in the EU. -

News Digest on Georgia

NEWS DIGEST ON GEORGIA July 13-16 Compiled by: Aleksandre Davitashvili Date: July 17, 2018 Occupied Regions Abkhazia Region 1. Saakashvili, Akhalaia, Kezerashvili, Okruashvili included in black list of occupied Abkhazia The "Organization of War Veterans" of occupied Abkhazia has presented “Khishba-Sigua List” to the de-facto parliament of Abkhazia. The following persons are included in the list set up in response to Georgian central government’s so-called “Otkhozoria-Tatunashvili List” : Ex-president Mikheil Saakashvili, former defence ministers – Bacho Akhalaia, Davit Kezerashvili, Irakli Okruashvili, Tengiz Kitovani and Gia Karkarashvili, former secretary of the National Security Council Irakli Batiashvili, former internal affairs minister Vano Merabishvili, Former head of the Joint Staff of the Georgian Armed Forces Zaza Gogava, former Defense Ministry senior official Megis Kardava, Brigadier General Mamuka Kurashvili, leader of "Forest Brothers" Davit Shengelia, former employee of the MIA Roman Shamatava and other persons are included in the list (IPN.GE, July 15, 2018). 2. Sergi Kapanadze says “Khishba-Sigua List” by de-facto Abkhazia is part of internal game and means nothing for Georgia There is no need to make a serious comment about “Khishba-Sigua List” as this list cannot have any effect on the public life of Georgia, Sergi Kapanadze, member of the “European Georgia” party, told reporters. The lawmaker believes that the list will not have legal or political consequences. (IPN.GE, July 15, 2018). Foreign Affairs 3. Jens Stoltenberg – We agreed to continue working together to prepare Georgia for NATO membership “We also met with the Presidents of Georgia and Ukraine. Together we discussed shared concerns. -

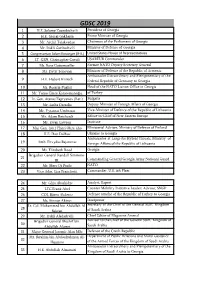

Gdsc 2019 1 H.E

GDSC 2019 1 H.E. Salome Zourabichvili President of Georgia 2 H.E. Giorgi Gakharia Prime Minister of Georgia 3 Mr. Archil Talakvadze Chairman of the Parliament of Georgia 4 Mr. Irakli Garibashvili Minister of Defence of Georgia 5 Congressman Adam Kinzinger (R-IL) United States House of Representatives 6 LT. GEN. Christopher Cavoli USAREUR Commander 7 Ms. Rose Gottemoeller Former NATO Deputy Secretary General 8 Mr. Davit Tonoyan Minister of Defence of the Republic of Armenia Ambassador Extraordinary and Plenipotentiary of the 9 H.E. Hubert Knirsch Federal Republic of Germany to Georgia 10 Ms. Rosaria Puglisi DeputyHead of Ministerthe NATO of LiaisonNational Office Defence in Georgia of the Republic 11 Mr. Yunus Emre Karaosmanoğlu Deputyof Turkey Minister of Defence of of the Republic of 12 Lt. Gen. Atanas Zapryanov (Ret.) Bulgaria 13 Mr. Lasha Darsalia Deputy Minister of Foreign Affairs of Georgia 14 Mr. Vytautas Umbrasas Vice-Minister of Defence of the Republic of Lithuania 15 Mr. Adam Reichardt SeniorEditor-in-Chief Research ofFellow, New EasternRoyal United Europe Services 16 Mr. Ewan Lawson Institute 17 Maj. Gen. (ret.) Harri Ohra-aho AmbassadorMinisterial Adviser, Extraordinary Ministry and of Plenipotentiary Defence of Finland of 18 H.E. Ihor Dolhov Ukraine to Georgia Ambassador-at-Large for Hybrid Threats, Ministry of 19 Amb. Eitvydas Bajarūnas ChargéForeign d’Affaires,Affairs of thea.i. Republicthe Embassy of Lithuania of the USA to 20 Ms. Elizabeth Rood Georgia Brigadier General Randall Simmons 21 JR. Director,Commanding Defense General Institution Georgia and Army Capacity National Building, Guard 22 Mr. Marc Di Paolo NATO 23 Vice Adm. -

Decree on Approving the Provisional Regulation of the Financial Supervision Agency of Georgia

GEORGIA DECREE ON APPROVING THE PROVISIONAL REGULATION OF THE FINANCIAL SUPERVISION AGENCY OF GEORGIA Important Disclaimer This translation has been generously provided by the Financial Supervision Agency of Georgia. This does not constitute an official translation and the translator and the EBRD cannot be held responsible for any inaccuracy or omission in the translation. The text should be used for information purposes only and appropriate legal advice should be sought as and when appropriate. DECREE N1 OF HEAD OF THE FINANCIAL SUPERVISION AGENCY OF GEORGIA April 24, 2008 Tbilisi On Approving Provisional Regulation of the Financial Supervision Agency of Georgia Pursuant to the Paragraph 5, Article 70 of the Organic Law of Georgia on National Bank of Georgia I decree: 1. Approve the attached Provisional Regulation of the Financial Supervision Agency of Georgia; 2. The Provisional Regulation shall become effective upon promulgation. 3. The validity period of the Provisional Regulation shall be defined according to Paragraph 7, Article 53 of the Organic Law of Georgia on National Bank of Georgia prior to approval of the Regulation of the Financial Supervision Agency of Georgia by the Council of the Financial Supervision Agency of Georgia. G. Kadagidze Annex Financial Supervision Agency of Georgia Provisional Regulation Chapter I General Provisions Article 1. Status and Grounds for Establishing of the Agency 1. Financial Supervision Agency of Georgia (hereinafter referred to as “the Agency”) is a legal entity of the public law, established with the National Bank of Georgia, pursuant to the Organic Law of Georgia on the National Bank of Georgia and its main objective is to exercise state supervision over the financial sector. -

Georgian Polyphony in a Century of Research: Foreword from the Editors

In: Echoes from Georgia: Seventeen Arguments on Georgian Polyphony. Rusudan Tsurtsumia and Joseph Jordania (Eds.). New York: Nova Science, 2010: xvii-xxii GEORGIAN POLYPHONY IN A CENTURY OF RESEARCH: FOREWORD FROM THE EDITORS Joseph Jordania and Rusudan Tsurtsumia This collection represents some of the most important authors and their writings about Georgian traditional polyphony for the last century. The collection is designed to give the reader the most possibly complete picture of the research on Georgian polyphony. Articles are given in a chronological order, and the original year of the publication (or completing the work) is given at every entry. As the article of Simha Arom and Polo Vallejo gives the comprehensive review of the whole collection, we are going instead to give a reader more general picture of research directions in the studies of Georgian traditional polyphony. We can roughly divide the whole research activities about Georgian traditional polyphony into six periods: (1) before the 1860s, (2) from the 1860s to 1900, (3) from the 1900s to 1930, (4) from the 1930s to 1950, (5) from the 1950s to 1990, and (6) from the 1990s till today. The first period (which lasted longest, which is usual for many time-based classifications), covers the period before the 1860s. Two important names from Georgian cultural history stand out from this period: Sulkhan-Saba Orbeliani (17th-18th centuries), and Ioane Bagrationi (beginning of the 18th-19th centuries). Both of them were highly educated people by the standards of their time. Ioane Bagrationi (1768-1830), known also as Batonishvili (lit. “Prince”) was the heir of Bagrationi dynasty of Georgian kings. -

Tbilisi in Figures 2018

TBILISI IN FIGURES 2018 1 Economic Development Office Tbilisi City Hall TBILISI Georgia PREFACE The annual edition of Tbilisi Statistics overview is published by the Economic Development Office of Tbilisi City Hall. The publication provides general information on city developments and captures main economic trends. 4 CONTENTS International Ranking 2018 6 History of Tbilisi 8 Urban Area and Climate 11 Politics and Urban Administration 16 People in Tbilisi 19 Living in Tbilisi 23 Tourism in Tbilisi 26 Culture & Leisure 29 Education & Research 32 Economy of Tbilisi 34 Traffic and Mobility 43 International Cooperation 47 5 International Ranking 2018 6 DOING BUSINESS 1st place in Europe&Central Asia 9th place Worldwide ECONOMIC FREEDOM INDEX 9th place in Europe 16th place Worldwide THE GOOD COUNTRY 11th place in Open Trade Worldwide THE WORLDS CHEAPEST CITIES 3rd place in Central Asia 11th place Worldwide International Rankings 2018 7 History of Tbilisi 8 IV century the most important crossroad in Georgia VI century the capital city and the political center of the country XII century the cultural center of Georgia and the whole Caucasus 1755 A philosophical Seminary in Tbilisi 1872-1883 Establishment of railway with Poti, Batumi and Baku History of Tbilisi 9 1918 The First Democratic Republic of Georgia 1918 Tbilisi State University 1928 Tbilisi International Airport 1966 establishment of Tbilisi Metro 2010 the first direct Mayoral elections of the city History of Tbilisi 10 Urban Area and Climate 11 Land Use Urbanized area: City area 502 km2 158 km2 Green space: 145.5 km2 Perimeter 150.5 km Density: 2 217 pers. -

First Capitals of Armenia and Georgia: Armawir and Armazi (Problems of Early Ethnic Associations)

First Capitals of Armenia and Georgia: Armawir and Armazi (Problems of Early Ethnic Associations) Armen Petrosyan Institute of Archaeology and Ethnography, Yerevan The foundation legends of the first capitals of Armenia and Georgia – Armawir and Armazi – have several common features. A specific cult of the moon god is attested in both cities in the triadic temples along with the supreme thunder god and the sun god. The names of Armawir and Armazi may be associated with the Anatolian Arma- ‘moon (god).’ The Armenian ethnonym (exonym) Armen may also be derived from the same stem. The sacred character of cultic localities is extremely enduring. The cults were changed, but the localities kept their sacred character for millennia. At the transition to a new religious system the new cults were often simply imposed on the old ones (e.g., the old temple was renamed after a new deity, or the new temple was built on the site or near the ruins of the old one). The new deities inherited the characteristics of the old ones, or, one may say, the old cults were simply renamed, which could have been accompanied by some changes of the cult practices. Evidently, in the new system more or less comparable images were chosen to replace the old ones: similarity of functions, rituals, names, concurrence of days of cult, etc (Petrosyan 2006: 4 f.; Petrosyan 2007a: 175).1 On the other hand, in the course of religious changes, old gods often descend to the lower level of epic heroes. Thus, the heroes of the Armenian ethnogonic legends and the epic “Daredevils of Sasun” are derived from ancient local gods: e.g., Sanasar, who obtains the 1For numerous examples of preservation of pre-Urartian and Urartian holy places in medieval Armenia, see, e.g., Hmayakyan and Sanamyan 2001). -

Regulating Trans-Ingur/I Economic Relations Views from Two Banks

RegUlating tRans-ingUR/i economic Relations Views fRom two Banks July 2011 Understanding conflict. Building peace. this initiative is funded by the european union about international alert international alert is a 25-year-old independent peacebuilding organisation. We work with people who are directly affected by violent conflict to improve their prospects of peace. and we seek to influence the policies and ways of working of governments, international organisations like the un and multinational companies, to reduce conflict risk and increase the prospects of peace. We work in africa, several parts of asia, the south Caucasus, the Middle east and Latin america and have recently started work in the uK. our policy work focuses on several key themes that influence prospects for peace and security – the economy, climate change, gender, the role of international institutions, the impact of development aid, and the effect of good and bad governance. We are one of the world’s leading peacebuilding nGos with more than 155 staff based in London and 15 field offices. to learn more about how and where we work, visit www.international-alert.org. this publication has been made possible with the help of the uK Conflict pool and the european union instrument of stability. its contents are the sole responsibility of international alert and can in no way be regarded as reflecting the point of view of the european union or the uK government. © international alert 2011 all rights reserved. no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without full attribution. -

![Survey on Political Attitudes April 2019 1. [SHOW CARD 1] There Are](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0963/survey-on-political-attitudes-april-2019-1-show-card-1-there-are-800963.webp)

Survey on Political Attitudes April 2019 1. [SHOW CARD 1] There Are

Survey on Political Attitudes April 2019 1. [SHOW CARD 1] There are different opinions regarding the direction in which Georgia is going. Using this card, please, rate your answer. [Interviewer: Only one answer.] Georgia is definitely going in the wrong direction 1 Georgia is mainly going in the wrong direction 2 Georgia is not changing at all 3 Georgia is going mainly in the right direction 4 Georgia is definitely going in the right direction 5 (Don’t know) -1 (Refuse to answer) -2 2. [SHOW CARD 2] Using this card, please tell me, how would you rate the performance of the current government? Very badly 1 Badly 2 Well 3 Very well 4 (Don’t know) -1 (Refuse to answer) -2 Performance of Institutions and Leaders 3. [SHOW CARD 3] How would you rate the performance of…? [Read out] Well Badly answer) Average Very well Very (Refuse to (Refuse Very badly Very (Don’t know) (Don’t 1 Prime Minister Mamuka 1 2 3 4 5 -1 -2 Bakhtadze 2 President Salome 1 2 3 4 5 -1 -2 Zourabichvili 3 The Speaker of the Parliament 1 2 3 4 5 -1 -2 Irakli Kobakhidze 4 Mayor of Tbilisi Kakha 1 2 3 4 5 -1 -2 Kaladze (Tbilisi only) 5 Your Sakrebulo 1 2 3 4 5 -1 -2 6 The Parliament 1 2 3 4 5 -1 -2 7 The Courts 1 2 3 4 5 -1 -2 8 Georgian army 1 2 3 4 5 -1 -2 9 Georgian police 1 2 3 4 5 -1 -2 10 Office of the Ombudsman 1 2 3 4 5 -1 -2 11 Office of the Chief Prosecutor 1 2 3 4 5 -1 -2 12 Public Service Halls 1 2 3 4 5 -1 -2 13 Georgian Orthodox Church 1 2 3 4 5 -1 -2 4. -

Hazelnuts and Honey Highlight Georgia's Export Potential

SOLAR PANELS TO BE PRODUCED GEORGIAN BUSINESSES A BILLION EUROS FOR AT KUTAISI FREE ZONE EMBRACE COACHING CULTURE GEORGIA Investor.A Magazine Of The American Chamber Of Commerce In Georgia geISSUE 68 APRIL-MAY 2019 Hazelnuts and Honey Highlight Georgia’s Export Potential APRIL-MAY 2019 Investor.ge | 3 Investor.ge CONTENT 6 Investment News Investor.ge provides a brief update on investments and changes in government policy that could impact the business environment. The information in this issue was taken from agenda.ge, a government supported website, and other sources. 8 Georgia Pushes for Close Relations with Japan Georgian Prime Minister Mamuka Bakhtadze led a delegation to Japan in March. The prime minister noted that it is possible to increase exports to Japan and increase foreign direct investments from Japanese businesses. 16 9 Solar Panels to Be Produced at Kutaisi Free Zone 10 Georgia Goes All in On Education – Way to Freedom Initiative 11 Breathe a sigh of relief: Georgian government acts to improve air quality 16 A Billion Euros for Georgia: An interview with investor Oleg Ossinovski 19 Georgian Hazelnuts and Honey Highlight Export Potential Georgian agriculture exports are steadily increasing: in 2018 the country exported $959.2 million worth of agricultural products, up 23.2 percent compared to 19 2017. Exports to the EU are still dwarfed by the demand from other countries, but two products — hazelnuts and honey — underscore the potential for growth. 23 Explainer: Anaklia Deep-Sea Port 25 Georgia Ski Resorts Prepare to Host Freestyle Ski and Snowboard World Championships Georgian ski resorts are steadily growing in popularity.