The Creation of an Independent Agricultural Press in the Antebellum North

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Golden Gate Grooves, January 2014

Golden Gate Grooves, January 2014 CD REVIEWS Billy Boy Arnold, Charlie Musselwhite, The singers/harmonica players under whose names Remembering Little Walter was issued are an enviable Mark Hummel, Sugar Ray Norcia, James all-star assemblage: Hummel, Harman, Charlie Harman, Remembering Little Walter Musselwhite, Billy Boy Arnold, and Sugar Ray Norcia. Together they make up something like 50% of any by Tom Hyslop reasonable person’s list of the pre-eminent living Latter-day harp men talk harmonica players, and the environment, as one might about Big Walter’s tone, expect, makes for committed and spirited emulate the conversational performances. Sugar Ray’s intense “Mean Old World” is styles of both Sonny Boys, dynamite, as is Musselwhite’s take on the up-tempo admire the power and “One Of These Mornings,” a relative rarity, which also playfulness of Cotton, and features a daredevil guitar break. Tone and dynamics dig Junior Wells’s attitude. are at an impossibly high level throughout—Hummel Some may work on Jimmy and the band dial in a perfect late-night mood on “Blue Reed’s high-end approach, Light,” and the way Harman drives “Crazy Mixed Up or give lip service to Snooky World” hard before breaking it down to a whisper at Pryor or even Louis Myers. But Marion Walter Jacobs the end is masterly. Billy Boy’s “Can’t Hold Out Much was The Man, the player whose stylistic innovations Longer” is splendid on every level. revolutionized the way the instrument was played, and whose technique, taste, and tones continue to baffle That recaps only about half of the program, but the rest and inspire musicians more than 60 years after his of the songs (each performer sings two) are excellent as debut, and nearly 45 years after his untimely death. -

The True History Regarding Alleged Connection of the Order of Ancient

' * ! HON AND MURDER R wMW'mjwi •:._; •' mmimmmm v« . IAMES A GIBSON LIBRARY BROCK UNIVERSITY ST. CATHARINES ON Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2012 with funding from Brock University - University of Toronto Libraries http://archive.org/details/truehistoryregarOOhunt THE TRUE HISTORY REGARDING ALLEGED CONNECTION OF THE ORDER OF ANCIENT. FREE AND ACCEPTED MASONS WITH THE ABDUCTION AND MURDER OF WILLIAM MORGAN, Tn Western New York, in 1826. TOGETHER WITH MUCH interesting and Valuable Contemporary History. COMPILED FROM AUTHENTIC DOCUMENTS AND RECORDS. BY P, C. HUNTINGTON, M. W. HAZEN CO., New York. COPYRIGHT. P. C. HUNTINGTON. TO THE ORDER OF ANCIENT, FREE AND ACCEPTED MASONS, WHOSE PATRIOTISM, PHILANTHROPY AND BENEFICENT INFLUENCE ARE WIDE AS HUMAN LIFE, THIS VOLUME IS RESPECTFULLY DEDICATED. PREFACE. The first edition of "Masonic Light" was issued a little more than six years ago, and it is not too much to say was commended by those interested. Since that time a large amount of interesting and valuable material and history relative to this affair has come to the compiler's hand, covering and completing the argument, and adding the climax of evidence regard- ing the false statements of Anti-Masons. Chapters X and XI which comprise the added records will be found replete with interesting and convincing facts. As there is nothing that tortures bigoted assertion more than history—it is confidently believed that the publication of this volume of historic facts will be ap- preciated by all lovers of the truth. P. C. H. Chicago, August, 1886. CONTENTS. CHAPTER I. Introduction 7 CHAPTER II. Morgan and his Coadjutors 24 CHAPTER III. -

Jan. 24, 1970 – Mike Bloomfield & Nick Gravenites

Jan. 24, 1970 – Mike Bloomfield & Nick Gravenites – 750 Vallejo In North Beach, SF “The Jam” Mike Bloomfield and friends at Fillmore West - January 30-31-Feb. 1-2, 1970? Feb. 11, 1970 -- Fillmore West -- Benefit for Magic Sam featuring: Butterfield Blues Band / Mike Bloomfield & Friends / Elvin Bishop Group / Charlie Musselwhite / Nick Gravenites Feb. 28, 1970 – Mike Bloomfield, Keystone Korner, SF March 19, 1970 – Elvin Bishop Group plays Keystone Korner , SF Bloomfield was supposed to show for a jam. Did he? March 27,28, 1970 – Mike Bloomfield and Nick Gravenites, Keystone Korner ***** MICHAEL BLOOMFIELD AND FRIENDS 1970. Feb. 27. Eagles Auditorium, Seattle 1. “Wine” (8.00) This is the encore from Seattle added on the bootleg as a “filler”! The rest is from Long Beach Auditorium Apr. 8, 1971. 1970 1 – CDR “JAMES COTTON W/MIKE BLOOMFIELD AND FRIENDS” Bootleg 578 ***** JANIS JOPLIN AND THE BUTTERFIELD BLUES BAND 1970. Mar. 28. Columbia Studio D, Hollywood, CA Janis Joplin, vocals - Paul Butterfield, hca - Mike Bloomfield, guitar - Mark Naftalin, organ - Rod Hicks, bass - George Davidson, drums - Gene Dinwiddle, soprano sax, tenor sax - Trevor Lawrence, baritone sax - Steve Madaio, trumpet 1. “One Night Stand” (Version 1) (3.01) 2. “One Night Stand” (Version 2) wrong speed 1982 1 – LP “FAREWELL SONG” CBS 32793 (NL) 1992 1 – CD “FAREWELL SONG” COLUMBIA 484458 2 (US) ?? 2 – CD-3 BOX SET CBS ***** SAM LAY 1970 Producer Nick Gravenites (and Michael Bloomfield) Sam Lay, dr, vocals - Michael Bloomfield, guitar - Bob Jones, dr – bass ? – hca ? – piano ? – organ ? Probably all of The Butterfield Blues Band is playing. Mark Naftalin, Barry Goldberg, Paul Butterfield 1. -

John Lee Hooker 1991.Pdf

PERFORMERS John Lee Hooker BY JOHN M I L W A R D H E BLUES ACCORDING TO John Lee Hooker is a propulsive drone of a guitar tuned to open G, a foot stomping out a beat that wouldn’t know how to quit, and a bear of a voice that knows its way around the woods. He plays big-city, big-beat blues born in the Mississippi Delta. Blame it on the boogie, and you’re blaming it on John Lee Hooker. Without the music of John Lee Hooker, Jim Morrison two dozen labels, creating one of the most confusing wouldn’t have known of crawling kingsnakes, and George discographies in blues history. Hooker employed such Thorogood wouldn’t have ordered up “One Bourbon, One pseudonyms as Texas Slim, Birmingham Sam, Delta John, Scotch, One Beer.” Van Morrison would not have influenced John Lee Booker, and Boogie Man. Most of his rhythm & generations of rock singers by personalizing the idiosyncratic blues hits appeared on Vee jay Records, including “Crawlin’ emotional landscape of Hooker’s fevered blues. Kingsnake,” "No Shoes,” and “Boom Boom”—John Lee’s sole Hooker inspired these and countless other boogie chil entry on the pop singles chart, in 1962. dren with blues that don’t In the late ’50s, Hooker adhere to a strict 12-bar T H E BLUES ALONE found a whole new audience structure, but move in re Detroit businessman Bernard Besman (in partnership with club owner Lee among the white fans of the sponse to the singer’s singu Sensation) issued John Lee Hooker’s first records in 1948 on the Sensation la folk revival. -

Extracts from Nick Gravenite's Book

EXTRACTS FROM NICK GRAVENITE’S BOOK- “BAD TALKING BLUESMAN” It's not so easy to introduce Nick Gravenites because the man has done so many things that one can easily write a book or build a web site only dedicated to Gravenites who is singer, songwriter, guitarist, and producer in one person. Subsequently everything found on this page concerning Nick can only be described as incomplete. Nevertheless let's start with a short introduction Taxim Records added to one of their Bay Area Blues Sampler 'More Bay Area Blues' which contains the song 'Hard Thing' by Nick. 'Nick Gravenites grew up on the southside of Chicago hanging out in the mid- 50's with a coterie of misfit white kids - Elvin Bishop, Paul Butterfield, Michael Bloomfield - who went on to form that protean powerhouse of watershed white blues, The Paul Butterfield Blues Band. Learning their lessons first-hand from the southside greats - Muddy Waters, Buddy Guy, Howlin' Wolf, Jimmy Reed, Otis Rush - Gravenites & Co. burst open the seams of the scene with a feverish intensity and undeniable authenticity, redefining the blues with as much impact as the introduction of electric instrumentation had 15 years earlier. From the late 50's through the mid 60's, Gravenites gravitated between Chicago and San Francisco, establishing himself in the Bay Area in 1965. In addition to authoring the classic "Born In Chicago" and the groundbreaking "East West" for Butterfield, Gravenites scribed hits for Janis Joplin and has his songs recorded by Big Brother and the Holding Company, Michael Bloomfield, the Electric Flag (of which Gravenites was a founding member), Pure Prairie League, Tracy Nelson, Roy Buchana, Jimmy Witherspoon as well as blues giants Howlin' Wolf, Otis Rush, and James Cotton. -

C:\Corruption\Bank Chartering Revision September 2004.Wpd

Bank Chartering and Political Corruption in Antebellum New York: Free Banking as Reform Howard Bodenhorn Lafayette College and NBER bodenhoh @ lafayette.edu Revised April 2004 Current revision September 2004 Abstract: One traditional and oft-repeated explanation of the political impetus behind free banking connects the rise of Jacksonian populism and a rejection of the privileges associated with corporate chartering. A second views free banking as an ill-informed inflationist, pro-business response to the financial panic of 1837. This essay argues that both explanations are lacking. Free banking was the progeny of the corruption associated with bank chartering and reflected social, political and economic backlashes against corruption dating to the late-1810s. Three strands of political thought -- Antimasonic egalitarianism, Jacksonian pragmatism, and pro-business American Whiggism -- converged in the 1830s and led to economic reform. Equality of treatment was the political watchword of the 1830s and free banking was but one manifestation of this broader impulse. Prepared for NBER Conference on Corruption and Reform. I thank Lee Alston, Michael Bordo, Andrew Economopoulos, Ed Glaeser, Stephen Quinn, Hugh Rockoff, Jay Shambaugh, John Wallis, Eugene White, Robert E. Wright, as well as seminar participants at Rutgers University, NYU and the NBER for many useful comments and suggestions on earlier drafts. Special thanks go to Claudia Goldin who provided extensive and valuable comments. I thank Pam Bodenhorn for valuable research assistance. -1- “He saw in the system what he thought a most dangerous political engine, which might in the hands of bad men be used for bad purposes.”1 1. Introduction Government policies toward business can be categorized into three types: minimal, maximal, and decentralized (Frye and Shleifer 1997). -

Modern Catskill

n8 HISTORY OF GREENE COUNTY. a joint will, in which th ey devised the lands in th e p at Several low ridges ex tend throug h the town, para llel ent to their children, Dirck, J aco b, Cornelius, Anna Kat with the river. The most conspicuous of these are th e rina, wife of Anthony Van Schaick, and Chri st in a, wife Ka lk berg , from one to two miles in land, a limes tone of David Van Dyck. Cornelius in r740 obtained a con ridge 50 to 100 feet high, and the L ittl e Mountains, a firmatory patent for his share in the inheritance . r:rnge of eleva tions reac hin g 300 to 500 feet, two or three miles further west. The latter are sometimes call ed the KISKATOM PATENT. Hooge -ber gs. Of th e main Catsk ill Mountains , parts of The plain which lies alm ost at the base of the Catskill the east ern slope of North and So uth Mountains and Mountain s was ca lled by th e Indians Kiskatominakauke, High Peak are the southwes tern part of this town . A that is to say, th e place of thin-shelled hickory nu ts or rich agricultural district borders the river , from Catskill shag-barks . The nam e, in a corrupted form, first occurs down to the gre at bend known as the Inbogt about four in a deed dated in 1708. miles below. Fruit raising is engaged in to a cons idera This pl ace was bought by H enry Beekman from th e ble extent, an d many fine orchards of choice pea r trees Indians, and in 17 r 7 he rec eived a patent for a portion are to be seen . -

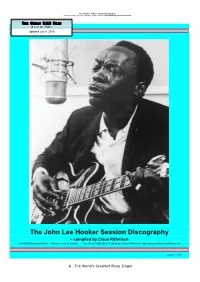

Complete John Lee Hooker Session Discography

The Complete John Lee Hooker Discography: from The Great R&B-files Created by Claus Röhnisch: http://www.rhythm-and-blues.info The Great R&B Files (# 2 of 12) PaRT i Updated July 8, 2019 The John Lee Hooker Session Discography - compiled by Claus Röhnisch The R&B Pioneers Series – Volume Two of twelve The Great R&B-files Created by Claus Röhnisch: http://www.rhythm-and-blues.info page 1 (94) 1 The World’s Greatest Blues Singer The Complete John Lee Hooker Discography: from The Great R&B-files Created by Claus Röhnisch: http://www.rhythm-and-blues.info The John Lee Hooker Session Discography - compiled by Claus Röhnisch John Lee Hooker – The World’s Greatest Blues Singer / The R&B Pioneers Series – Volume Two of twelve Below: Hooker’s first record, his JVB single of 1953, and the famous “Boom Boom”. The “Hooker” Box, Vee-Jay’s version of the Hooker classic, the original “The Healer” album on Chameleon. BluesWay 1968 single “Mr. Lucky”, the Craft Recordings album of March 2017, and the French version of the Crown LP “The Blues”. Right: Hooker in his prime. Two images from Hooker’s grave in the Chapel of The Chimes, Oakland, California; and a Mississippi Blues Trail Marker on Hwy. 3 in Quitman County (Vance, Missisippi memorial stone - note birth date c. 1917). 2 The World’s Greatest Blues Singer The Complete John Lee Hooker Discography: from The Great R&B-files Created by Claus Röhnisch: http://www.rhythm-and-blues.info . December 31, 1948 (probably not, but possibly early 1949) - very rare (and very early) publicity photo of the new-found Blues Star (playin’ his Gibson ES 175). -

Complete John Lee Hooker Session Discography

The Complete John Lee Hooker Discography –Part II from The Great R&B-files Created by Claus Röhnisch: http://www.rhythm-and-blues.info The Great R&B Files (# 2 of 12) Part II Updated 2017-09-23 MAIN CONTENTS: page Hooker Singles in Disguise 82 Hooker’s First and Last Albums 94 The Body & Soul CD-series 112 Giant of Blues – an Essay by Les Fancourt 114 The Complete EP Collection 118 The Real Best of Selection (with Trivia) 132 The three “whole career” double-CDs 137 JLH Recording Scale 138 Bootlegs and DVDs 142 Nuthin’ but the Best! – Fictional Album 145 The World’s Greatest Blues Singer Supplement to The John Lee Hooker Session Discography http://www.rhythm-and-blues.info/02_HookerSessionDiscography.pdf Part II of the John Lee Hooker Session Discography - compiled by Claus Röhnisch - The R&B Pioneers Series: Volume Two (Part II) of twelve The Great R&B-files Created by Claus Röhnisch: http://www.rhythm-and-blues.info page 81 (of 164) The Complete John Lee Hooker Discography – Part II from The Great R&B-files Created by Claus Röhnisch: http://www.rhythm-and-blues.info The BEST of the CDs featuring Johnnie’s pirate recordings Check Ultimate CD’s entries in the Session Discography, Part One for more details ….. and check Singles discography for pseudonyms. ”Boogie Awhile” – Krazy Kat; ”Early Years: The Classic Savoy Sessions” (1948/49 and 1961) - MetroDoubles; ”Savoy Blues Legends: Detroit 1948-1949” – Savoy; ”Danceland Years” – Pointblank ”I’m A Boogie Man: The Essential Masters 1948-1953” – Varese Sarabande; ”The Boogie Man” – Properbox; -

Howlin Wolf 1991.Pdf

FOREFATHERS Howlin’ W olf JUNE 10,1910 - JANUARY 10,1976 BY PETER GURALNICK OWLIN’ WOLF WAS LARGER than life in every respect. As an entertainer, as an individual, and as a bluesman, he was outsized, unpredictable, and always his own man. He was a great blues singer who pos sessed that quality of egocentric self-absorption that is the mark of the true showman. To many people this may seem contradictory, but Wolf proved that to its natural audience blues is not all pain and suffering, but is instead a kind of re his voice that was his crowning glory, a voice which could lease. When you listen to the blues, you should be moved; fairly be called inimitable, cutting with a sandpaper rasp and doubtless you should take the deep blues of a singer like overwhelming ferocity but retaining at the same time a curi Muddy Waters or Howlin’ Wolf with the sense of dignity that ous delicacy of shading, a sense of dynamics and subtlety of is intended. You should also come away with a smile on your approach that set it off from any other blues singer’s in that lips. rich tradition. It combined the rough phrasing of Patton with Howlin’ Wolf was a totally enigmatic personality. He was the vocal filigree of Tommy Johnson and its familial descen a man at once complex, driven, and dant: the blue yodel of Jimmie altogether impossible to read. I think WOLF’S RIGHT HAND: Rodgers, a white country singer he was as much a mystery to his HUBERT SUMLIN, LEAD GUITAR whom Wolf always admired. -

William Morgan, Or, Political Anti-Masonry

WILLIAM MORGAN; POLITICAL ANTI-MASONRY, 1 1 , GROWTH AND DECADENCE. BY ' r ROB MORRIS, LL.D., t 0 N- X k Ita comparatum esse homlnum naturam omnium, «J Aliena ut melius videant et dijudicent, Quam sua! —Terence. (Strange nature In Anti-Masons, that they can see and judge vhe affairs of Freemasons better than their own!) FIFTH THOUSAND. N E W YORK: ROBERT MACOY, MASONIC PUBLISHER, No. 4 B arc lat St r e e t . 1884. «?- - ° 1 ' Digitized by A-" < AI 7 /<■■ Z Os • 3 ' A- syibi.2. C o p y r ig h t , 1883. By ROB MORRIS, LL.D. ______ I KNIGHT & LEONARD . I Digitized by U o o Q l e TO THE EHEEMASONS OF CHICAGO AND VICINITY, W HOSE B R O T H E R L Y KINDNESS I HAVE LONG EXPERIENCED, AND WHOSE PATRONAGE OF THE PRESENT WORK HAS GIVEN ME RENEWED COURAGE TO PERSEVERE IN MY LIFE-TIME DEVOTION TO MASONRY, THIS FIFTH EDITION IS FRATERNALLY DEDICATED. Digitized by P E E FACE. I t is well nigh two score years since a gentleman at Oxford, Mississippi, then, as now, honored and beloved,* pronounced the mystic words that proclaimed me a member of the Masonic fraternity. I have not forgotten— can I ever forget? — even the smallest details of the time, place and occasion. The cold, stormy night in March; the little circle of ten or fifteen, all well known to me as neighbors and friends; the dilapidated apartment, then transformed under the magic of Masonic symbolism into “ the checkered pave ment of King Solomon’s Temple” ; the ceremonies, quaint and pregnant with ancient saws and apothegms; finally, the E x p l a n a t o r y L e c t u r e s , so eloquently delivered by one whose equal in that branch of inculcation I have rarely met through all subsequent years,— such is the vision that recurs vividly to my mind as, in the loneliness of my study, I indite this preface. -

And Add To), Provided That Credit Is Given to Michael Erlewine for Any Use of the Data Enclosed Here

POSTER DATA COMPILED BY MICHAEL ERLEWINE Copyright © 2003-2020 by Michael Erlewine THIS DATA IS FREE TO USE, SHARE, (AND ADD TO), PROVIDED THAT CREDIT IS GIVEN TO MICHAEL ERLEWINE FOR ANY USE OF THE DATA ENCLOSED HERE. There is no guarantee that this data is complete or without errors and typos. And any prices are sure to be out of date. This is just a beginning to document this important field of study. [email protected] ------------------------------ ANT 1975-04-11 P-1 --------- 1975-04-11 / ANT CP020141 / XK19750411 Buckwheat Zydeco at Antone's - Austin, TX Venue: Antone's Items: Original poster ANT Edition 1 / CP020141 / XK19750411 ANT / NONE / XK1975041 Performers: 1975-04-11: Antone's Buckwheat Zydeco ------------------------------ ANT 1976-04- P-1 --------- 1976-04- / ANT CP008155 / CP03400 Muddy Waters Birthday Party at Antone's - Austin, TX Notes: NONE Private Notes: Antones * Venue: Antone's Items: Original poster ANT Edition 1 / CP008155 / CP03400 Performers: 1976-04-: Antone's Muddy Waters ------------------------------ ANT-Antones 1976-05-04 P-1 --------- 1976-05-04 / ANT Antones CP008163 / CP03408 Big Walter Horton at Antone's - Austin, TX Private Notes: Antones Venue: Antone's Items: Original poster ANT-Antones Edition 1 / CP008163 / CP03408 ANT-Antones / CP020153 / XK19760504 ANT-Antones / NONE / XK1976050 Performers: 1976-05-04: Antone's Big Walter Horton ------------------------------ ANT 1976-09-28 P-1 --------- 1976-09-28 / ANT CP020160 / XK19760928 John Lee Hooker at Antone's - Austin, TX Venue: Antone's Items: Original poster ANT Edition 1 / CP020160 / XK19760928 ANT / CP020866 / XM19760928 ANT / NONE / XM1976092 Performers: 1976-09-28: Antone's John Lee Hooker ------------------------------ ANT 1976-09-28 ® --------- 1976-09-28 / ANT John Lee Hooker at Antone's - Austin, TX Artist: Danny Garrett Venue: Antone's Items: ANT / Performers: 1976-09-28: Antone's John Lee Hooker ------------------------------ ANT 1976-11-16 P-1 --------- 1976-11-16 / ANT CP015123 / ME0270 B.B.