Writing in the Key of “W”

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Kate Daley – Song List

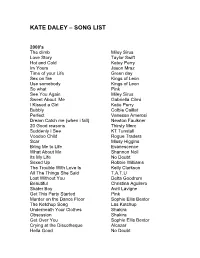

KATE DALEY – SONG LIST 2000's The climb Miley Sirus Love Story Taylor Swift Hot and Cold Katey Perry Im Yours Jason Mraz Time of your Life Green day Sex on fire Kings of Leon Use somebody Kings of Leon So what Pink See You Again Miley Sirus Sweet About Me Gabriella Cilmi I Kissed a Girl Katie Perry Bubbly Colbie Caillat Perfect Vanessa Amerosi Dream Catch me (when i fall) Newton Faulkner 20 Good reasons Thirsty Merc Suddenly I See KT Tunstall Voodoo Child Rogue Traders Scar Missy Higgins Bring Me to Life Evanescence What About Me Shannon Noll Its My Life No Doubt Sexed Up Robbie Williams The Trouble With Love Is Kelly Clarkson All The Things She Said T.A.T.U Lost Without You Delta Goodrem Beautiful Christina Aguilero Skater Boy Avril Lavigne Get This Party Started Pink Murder on the Dance Floor Sophie Ellis Bextor The Ketchup Song Las Ketchup Underneath Your Clothes Shakira Obsession Shakira Get Over You Sophie Ellis Bextor Crying at the Discotheque Alcazar Hella Good No Doubt Lets Get Loud Jennifer Lopez Don’t Stop Moving S Club 7 Cant Get you Out of My Head Kylie Minogue I’m Like a Bird Nelly Fertado Absolutely Everybody Vanessa Amorosi Fallin’ Alicia Keys I Need Somebody Bardot Lady marmalade Moulin Rouge Drops of Jupiter Train Out of Reach Gabrielle (Bridgett Jones Dairy) Hit em up in Style Blu Cantrell Breathless The Corrs Buses and trains Bachelor Girl Shine Vanessa Amorosi What took you so long Emma B Overload Sugarbabes Cant Fight the Moonlight Leeann Rhymes (Coyote Ugly) Sunshine on a Rainy Day Christine Anu On a Night Like This -

The Globalization of K-Pop: the Interplay of External and Internal Forces

THE GLOBALIZATION OF K-POP: THE INTERPLAY OF EXTERNAL AND INTERNAL FORCES Master Thesis presented by Hiu Yan Kong Furtwangen University MBA WS14/16 Matriculation Number 249536 May, 2016 Sworn Statement I hereby solemnly declare on my oath that the work presented has been carried out by me alone without any form of illicit assistance. All sources used have been fully quoted. (Signature, Date) Abstract This thesis aims to provide a comprehensive and systematic analysis about the growing popularity of Korean pop music (K-pop) worldwide in recent years. On one hand, the international expansion of K-pop can be understood as a result of the strategic planning and business execution that are created and carried out by the entertainment agencies. On the other hand, external circumstances such as the rise of social media also create a wide array of opportunities for K-pop to broaden its global appeal. The research explores the ways how the interplay between external circumstances and organizational strategies has jointly contributed to the global circulation of K-pop. The research starts with providing a general descriptive overview of K-pop. Following that, quantitative methods are applied to measure and assess the international recognition and global spread of K-pop. Next, a systematic approach is used to identify and analyze factors and forces that have important influences and implications on K-pop’s globalization. The analysis is carried out based on three levels of business environment which are macro, operating, and internal level. PEST analysis is applied to identify critical macro-environmental factors including political, economic, socio-cultural, and technological. -

Voices of Australia Rightsed | Voices of Australia Voices of Australia

Human rights education resources for teachers Photo: Anna Bauer Voices of Australia rightsED | Voices of Australia Voices of Australia Subjects: Civics and Citizenship, History, all Society and Human rights Environment subjects, English and Literature. education resources Level: Some activities are suited for Upper Primary (Years 5–6) Most suited to Upper Secondary (Year 10 and up) for teachers Time needed: There is enough material for a 10 week program, however activities could be used individually to suit topic requirements. Activities 1–4, and 7, 8 are for single lessons, activities 5 and 6 will require more substantial research time. Introduction This education resource is designed to complement the publication Voices of Australia: 30 years since the Racial Discrimination Act. The publication is available at: www.humanrights.gov.au/racial_discrimination/voices The stories in the Voices of Australia publication remind us that Australia is a society of many diverse communities. While it is an ancient land, and home to the world’s oldest continuing culture, it is also a young and vibrant multicultural society with nearly a quarter of Australians born overseas, and another quarter having at least one parent who was born in another country. The stories also remind us that within our diversity there are values that many of us share. One of these values is that racism and discrimination have no place in our communities. It is essential for all Australians to understand that equality before the law is not something that we should take for granted. It is essential that shared values be discussed at all levels in our communities in order to minimise the potential for conflict. -

Cotton and the Community: Exploring Changing Concepts of Identity and Community on Lancashire’S Cotton Frontier C.1890-1950

Cotton and the Community: Exploring Changing Concepts of Identity and Community on Lancashire’s Cotton Frontier c.1890-1950 By Jack Southern A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment for the requirements for the degree of a PhD, at the University of Central Lancashire April 2016 1 i University of Central Lancashire STUDENT DECLARATION FORM I declare that whilst being registered as a candidate of the research degree, I have not been a registered candidate or enrolled student for another aware of the University or other academic or professional institution. I declare that no material contained in this thesis has been used for any other submission for an academic award and is solely my own work. Signature of Candidate ________________________________________________ Type of Award: Doctor of Philosophy School: Education and Social Sciences ii ABSTRACT This thesis explores the evolution of identity and community within north east Lancashire during a period when the area gained regional and national prominence through its involvement in the cotton industry. It examines how the overarching shared culture of the area could evolve under altering economic conditions, and how expressions of identity fluctuated through the cotton industry’s peak and decline. In effect, it explores how local populations could shape and be shaped by the cotton industry. By focusing on a compact area with diverse settlements, this thesis contributes to the wider understanding of what it was to live in an area dominated by a single industry. The complex legacy that the cotton industry’s decline has had is explored through a range of settlement types, from large town to small village. -

James Taylor

JAMES TAYLOR Over the course of his long career, James Taylor has earned 40 gold, platinum and multi- platinum awards for a catalog running from 1970’s Sweet Baby James to his Grammy Award-winning efforts Hourglass (1997) and October Road (2002). Taylor’s first Greatest Hits album earned him the RIAA’s elite Diamond Award, given for sales in excess of 10 million units in the United States. For his accomplishments, James Taylor was honored with the 1998 Century Award, Billboard magazine’s highest accolade, bestowed for distinguished creative achievement. The year 2000 saw his induction into both the Rock ‘n’ Roll Hall of Fame and the prestigious Songwriter’s Hall of Fame. In 2007 he was nominated for a Grammy Award for James Taylor at Christmas. In 2008 Taylor garnered another Emmy nomination for One Man Band album. Raised in North Carolina, Taylor now lives in western Massachusetts. He has sold some 35 million albums throughout his career, which began back in 1968 when he was signed by Peter Asher to the Beatles’ Apple Records. The album James Taylor was his first and only solo effort for Apple, which came a year after his first working experience with Danny Kortchmar and the band Flying Machine. It was only a matter of time before Taylor would make his mark. Above all, there are the songs: “Fire and Rain,” “Country Road,” “Something in The Way She Moves,” ”Mexico,” “Shower The People,” “Your Smiling Face,” “Carolina In My Mind,” “Sweet Baby James,” “Don’t Let Me Be Lonely Tonight,” “You Can Close Your Eyes,” “Walking Man,” “Never Die Young,” “Shed A Little Light,” “Copperline” and many more. -

The English Occupational Song

UNIVERSITY OF UMEÅ DISSERTATION ISSN 0345-0155-ISBN 91-7174-649-8 From the Department of English, Faculty of Humanities, University of Umeå, Sweden. THE ENGLISH OCCUPATIONAL SONG AN ACADEMIC DISSERTATION which will, on the proper authority of the Chancellor's Office of Umeå University for passing the doctoral examination, be publicly defended in Hörsal E, Humanisthuset, on Saturday, May 23, at 10 a.m. Gerald Porter University of Umeå Umeå 1992 ABSTRACT THE ENGLISH OCCUPATIONAL SONG. Gerald Porter, FL, Department of English, University of Umeå, S 901 87, Sweden. This is the first full-length study in English of occupational songs. They occupy the space between rhythmic work songs and labour songs in that the occupation signifies. Occupation is a key territorial site. If the métier of the protagonist is mentioned in a ballad, it cannot be regarded as merely a piece of illustrative detail. On the contrary, it initiates a powerful series of connotations that control the narrative, while the song's specific features are drawn directly from the milieu of the performer. At the same time, occupational songs have to exist in a dialectical relationship with their milieu. On the one hand, they aspire to express the developing concerns of working people in a way that is simultaneously representational and metaphoric, and in this respect they display relative autonomy. On the other, they are subject to the mediation of the dominant or hegemonic culture for their dissemination. The discussion is song-based, concentrating on the occupation group rather than, as in several studies of recent years, the repertoire of a singer or the dynamics of a particular performance. -

There Is Hope! Practices and Interventions for Successful Treatment of Adult Survivors of Child Sexual Abuse ©

There Is Hope! Practices and Interventions for Successful Treatment of Adult Survivors of Child Sexual Abuse © Introduction [Edited: 11/30/2016] “Nonetheless, we are missing the boat!” At this time in our history, as a society, we are finally addressing sexual issues and sexual abuse issues more openly. This is an important progress. At home, we are hopefully doing a better job of teaching about sexuality than past generations did. We are teaching children in their pre-schools and in kindergartens about “Good Touch, Bad Touch”®. Societally, we more frequently are talking to our children about maintaining personal safety from “them”, about avoiding those ‘bad strangers’ who may be out there. “Even so, we are still missing the boat!” Surely, there have been victims whose sexual assault was perpetrated by a primarily unknown or a completely unknown stranger. A little boy who was pulled into a stranger’s car. A teenager who is raped by someone who was breaking-and-entering into her home. A college woman assaulted by a stalker. A young partier, slipped a date-rape drug at a party or in a bar, is sexually assaulted. Certainly, there are some dangerous strangers out there. As a result, we all do have to be aware of our surroundings and be reasonably vigilant in unfamiliar settings. And we do need to teach our kids about maintaining their personal safety from strangers. Nonetheless, while our society is warning children about ‘strangers’, we are still not providing them with adequate information about the dangers from molestation, rape, and incest by the ‘non-stranger’. -

Teaching and Learning Activities

TRUE BLUE? ON BEING AUSTRALIAN Teaching and learning activities True Blue? On Being Australian – Teaching and learning activities Published by Curriculum Corporation PO Box 177 Carlton South Vic 3053 Australia Tel: (03) 9207 9600 Fax: (03) 9639 1616 Email: [email protected] Website: www.curriculum.edu.au Copyright © National Australia Day Council 2008 Acknowledgement This product was funded by the Australian Government Department of Education, Employment and Workplace Relations. True Blue? On Being Australian – Teaching and learning activities can be found at the National Australia Day Council website: www.australiaday.gov.au/trueblue © National Australia Day Council 2008 TRUE BLUE? ON BEING AUSTRALIAN Teaching and learning activities ABOUT TRUE BLUE? AMBIVALENCES, ANXIETIES, COMPLEXITIES AND CONTRADICTIONS For well over a century Australians have been concerned to define a national identity. In her recently released study, Being Australian, Catriona Elder says: ‘Being Australian is not simply about the pleasure of the past and the excitement of the future... It is not just about that funny feeling a citizen might get when the Australian flag is raised at the Olympics. Being Australian also encompasses feelings, ideas and emotions that vary from joy to shame, guilt to confusion, hatred to love. Yet, in most national narratives these feelings of anxiety are erased or repressed in favour of the pleasurable aspects of national identity. Finding pleasure in being Australian is valuable; however exploring and explaining the anxiety and fear that lie at the heart of the idea of being Australian is also important.’ In the collection TRUE BLUE? we have attempted to problematise the notion of Australian identity for senior students. -

JAMES TAYLOR the Essential James Taylor

JAMES TAYLOR The Essential James Taylor 37 Tracks aus der gesamten Karriere des hochgeschätzten Songwriters auf 2 CDs Ab 11. September 2015 JAMES TAYLOR gilt als der Inbegriff eines Singer/Songwriters und dürfte zu den einflussreichsten amerikanischen Musikern der vergangenen viereinhalb Dekaden gehören. Der fünffache Grammy-Gewinner verkaufte bisher weit über 100 Millionen Tonträger, die mit insgesamt 10 US-Platinauszeichnungen belohnt wurden. Im Jahr 2000 wurde er gleichzeitig in die Rock’n’Roll Hall Of Fame und in die Songwriters‘ Hall Of Fame aufgenommen. Mit einer umfassenden Doppel-CD würdigt Rhino Rec. nun das fast fünfzig Jahre währende Schaffen des Ausnahme-Songwriters. The Essential James Taylor erscheint am 11. September! Die 37-Song-Compilation umfasst TAYLORs Schaffen in den Jahren von 1970-2002. 1969 unterschrieb der 1948 in Boston geborene TAYLOR einen Vertrag beim „Beatles- Label“ Apple Records und veröffentlichte im Jahr darauf das Album Sweet Baby James. Zu den großen und allbekannten Hits gehören Songs wie Carolina On My Mind, Sweet Baby James, Fire And Rain, Shower The People und You’ve Got A Friend, das zwar sein einziger Nummer 1-Hit blieb, ihm jedoch seinen ersten Grammy einbrachte. CD 1 ist vollständig TAYLORS Schaffen in den 70er Jahren gewidmet und enthält mit How Sweet It Is (To Be Loved By You), Handy Man, Walking Man (vom gleichnamigen 1974er Album) und Gorilla (ebenfalls ein Titeltrack für ein Album aus dem Jahr 1975) einige US-Top-5-Hits. Überdies findet man auf der Disc eine Live- Version von Steamroller, das stets eines der Konzerthighlights war. Dabei dürfen auch einige Fan-Lieblinge nicht fehlen, etwa Long Ago And Far Away von Mud Slide Slim And The Blue Horizon (1971), Something In The Way She Moves und Don’t Be Sad ‘Cause Your Sun Is Down, auf dem auch Stevie Wonder zu hören ist. -

"Millworker" by James Taylor

Millworker James Taylor Now my grandfather was a sailor, he blew in off the water My father was a farmer and I, his only daughter Took up with a no-good millworking man from Massachusetts Who dies from too much whiskey and leaves me these three faces to feed 5 Millwork ain't easy, millwork ain't hard Millwork it ain't nothing but an awful boring job I'm waiting for a daydream to take me through the morning And put me in my coffee break where I can have a sandwich and remember Then it's me and my machine for the rest of the morning 10 For the rest of the afternoon and the rest of my life Now my mind begins to wander to the days back on the farm I can see my father smiling at me, swinging on his arm I can hear my granddad's stories of the storms out on Lake Erie Where vessels and cargoes and fortunes and sailors' lives were lost 15 Yes, but it's my life has been wasted, and I have been the fool To let this manufacturer use my body for a tool I can ride home in the evening, staring at my hands Swearing by my sorrow that a young girl ought to stand a better chance Well may I work the mills just as long as I am able 20 And never meet the man whose name is on the label It be me and my machine for the rest of the morning And the rest of the afternoon gone, for the rest of my life Questions for Discussion and Writing 1. -

THE MARION MANUFACTURING MILL STRIKE of 1929 by Megan

A MISSING MOUNTAIN MEMORY: THE MARION MANUFACTURING MILL STRIKE OF 1929 by Megan Stevens A thesis submitted to the faculty of The University of North Carolina at Charlotte in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in History Charlotte 2020 Approved by: ______________________________ Dr. David GoldfielD ______________________________ Dr. Shepherd McKinley ______________________________ Dr. Jurgen Buchenau ii ©2020 Megan Stevens ALL RIGHTS RESERVED iii ABSTRACT MEGAN STEVENS. A Missing Mountain Memory: The Marion Manufacturing Mill Strike of 1929 . (Under the direction of DR. DAVID GOLDFIELD) In Marion, North Carolina, the local residents of the city and surrounding region have forgotten a tragic strike that took place at one of the local mills in 1929, though it was possibly the deadliest textile mill strike in the South. The strike, which officially took place between July 11, 1929 and October 2, 1929, was in response to inhumane labor practices and unsatisfactory pay. While the strike was supporteD by the United Textile Workers, it was primarily organizeD by the local strikers who were unhappy with their working conditions. While the UTW was not affiliated with the Communist Party, and the strikers in Marion were decidedly anti-communist, past and present criticisms of the strike revolve around the inaccurate perception of the strikers being led by communists, which turned their neighbors against them. The strike ended on October 2, 1929, when a group of deputies fired into a strike-line, killing six men and injuring an untold number of others. Rather than reconcile and heal from this event one could call the residents of the town, including the mill workers, experts at forgetting. -

Article of Rny Faith. -It Is Also the Last· Orticle of My Creed. Mahatma Gandhi

-·----- ----- · - -,. -_Jl{o AP.f2.1L_ Iq~~ . Non-violence is the first· article of rny faith. -It is also the last· orticle of my creed. Mahatma GandhI 'EDITOR: Chris E. Cell· MANAGEMENT STAFF: c:!bowski ADVERTISING: Kris Mal· Time for humanity to start ·.ASSOCIATE EDITORS: zahn . NEWS: Laura Stemweis · · Todd Sharp . AlP. Wong BUSINESS: Dean Koenig JI'EA'roREs: Kim Jacob- OFFICE MANAGE~: son . · . Elaine Yun-Lin Voo --_ - living what it preaches . SPORTS: Tamas Houlihan . OONTRJBUTORS: ENVIRONMENT: Andrew JW Fassbinder Savaglan · Cal Tamanji Tom Weiland It's funny. Here I sat wondering As the world's nations haggle over COPY EDITOR: Trudy Stewart . auisHavel what I was going to write about in my doctrine . and dogmatic differences, i . Susan Higgins editorial for the religion issue, when I humanity sinks closer to the point PHOTOGRAPHY: Rich · . Nanette Cable where religious dogmas won't mean a . Bumslde spotted a yellowing stack of old news Paul Gaertner papers here in the Pointer office . .. thing. Humanists are attacked froin . A~~Qtants: Fred Bobensee DebKellom : Mike Groricb Chocked full of the daily dose of mali many different religious corners, yet . ~~~Ss cious mayhem, one newspaper sur their beliefs in the essential goodness . QBAPBICS: Jayne Micb- 'PblfJinUi prisingly offered me an idea for an and promise of the hwnan race may llg. be what saves us from self-destruc Alalatant: BUl Glassen editorial about religion. There, in the ·=:.~ulloo creased upper righthand corner of tion. In the swirling, confusing mass .ADVJsoa: Dan HouUban . Laura 8ebnke BldtKaufman ... page eight was a story about a second of religious doctrines that bombard Amy Schroeder wall being erected to keep Protes the world community we need to find MikeDaebn tants and Catholics from each other's some conimon denominators.