Invisible Citizens

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Reading Habits and Preferences of LGBTIQ+ Youth Rachel S

St. Cloud State University theRepository at St. Cloud State Library Faculty Publications Library Services 2019 The Reading Habits and Preferences of LGBTIQ+ Youth Rachel S. Wexelbaum Saint Cloud State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.stcloudstate.edu/lrs_facpubs Part of the Library and Information Science Commons Recommended Citation Wexelbaum, Rachel S., "The Reading Habits and Preferences of LGBTIQ+ Youth" (2019). Library Faculty Publications. 62. https://repository.stcloudstate.edu/lrs_facpubs/62 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Library Services at theRepository at St. Cloud State. It has been accepted for inclusion in Library Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of theRepository at St. Cloud State. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Reading Habits and Preferences of LGBTIQ+ Youth Rachel Wexelbaum, St. Cloud State University, USA Abstract The author of this article presents the available findings on the reading habits and preferences of LGBTIQ+ youth. She will discuss the information seeking behavior of LGBTIQ+ youth and challenges that these youth face in locating LGBTIQ+ reading materials, whether in traditional book format or via social media. Finally, the author will provide recommendations to librarians on how to make LGBTIQ+ library resources more relevant for youth, as well as identify areas that require more research. Keywords: LGBT; LGBT library resources and services; reading; social -

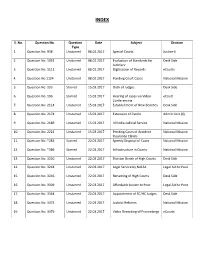

S. No. Question No. Question Type Date Subject Division 1. Question No. 938 Unstarred 08.02.2017 Special Courts Justice-II 2. Qu

INDEX S. No. Question No. Question Date Subject Division Type 1. Question No. 938 Unstarred 08.02.2017 Special Courts Justice-II 2. Question No. 1031 Unstarred 08.02.2017 Evaluation of Standards for Desk Side Judiciary 3. Question No. 1111 Unstarred 08.02.2017 Digitisation of Records eCourts 4. Question No.1124 Unstarred 08.02.2017 Pending Court Cases National Mission 5. Question No. 193 Starred 15.03.2017 Oath of Judges Desk Side 6. Question No. 196 Starred 15.03.2017 Hearing of cases via Video eCourt Conferencing 7. Question No. 2114 Unstarred 15.03.2017 Establishment of New Benches Desk Side 8. Question No. 2174 Unstarred 15.03.2017 Extension of Parole Admin Unit (II) 9. Question No. 2189 Unstarred 15.03.2017 All India Judicial Service National Mission 10. Question No. 2221 Unstarred 15.03.2017 Pending Cases of Accident National Mission Insurance Claims 11. Question No. *283 Starred 22.03.2017 Speedy Disposal of Cases National Mission 12. Question No. *286 Starred 22.03.2017 Infrastructure in Courts National Mission 13. Question No. 3230 Unstarred 22.03.2017 Division Bench of High Courts Desk Side 14. Question No. 3244 Unstarred 22.03.2017 Legal Service by NALSA Legal Aid to Poor 15. Question No. 3246 Unstarred 22.03.2017 Renaming of High Courts Desk Side 16. Question No. 3309 Unstarred 22.03.2017 Affordable Justice to Poor Legal Aid to Poor 17. Question No. 3364 Unstarred 22.03.2017 Appointment of SC/HC Judges Desk Side 18. Question No. 3373 Unstarred 22.03.2017 Judicial Reforms National Mission 19. -

Sfiff 2019 Program Here

SantaFeIndependent.com 2019 team and advisory board 2019 SFIFF TEAM Jacques Paisner Artistic Director Liesette Paisner Bailey Executive Director Jena Braziel Guest Service Director Derek Horne Director of Shorts Programmer Beau Farrell Associate Programmer Stephanie Love Office Manager Dawn Hoffman Events Manager Deb French Venue Coordinator Chris Bredenberg Tech Director Allie Salazar Graphic Designer Blake Lewis Headquarters Manager Castle Searcy Festival Dailies Adelaide Zhang Box Office Assistant Sarah Mease Box Office Assistant Eileen O’Brien MC Sage Paisner Photographer 2019 SFIFF ADVISORY BOARD Gary Farmer, Chair Chris Eyre Kirk Ellis David Sontag Alexandria Bombach Nicole Guillemet “A young Sundance” Alton Walpole —Indiewire Kimi Ginoza Green Paul Langland Beth Caldarello Xavier Horan “An all inclusive Marissa Juarez resort for cinephiles...” —Filmmaker Magazine “Bringing the community together” 505-349-1414 —Slant Magazine www.santafeindependent.com • [email protected] 418 Montezuma Ave. Suite 22 Santa Fe, NM 87501 3 AD AD welcome WELCOME Dear Santa Fe Independent Film Festival Visitors and Community, Welcome to Santa Fe, and to the festival The Albuquerque Journal calls “The Next Sundance.” The Santa Fe Independent Film Festival (SFIFF), now in its eleventh year, has become one of Santa Fe’s most celebrated annual events. I know you will enjoy SFIFF’s world-class programming and award-winning guests, including renowned ac- tors Jane Seymour and Tantoo Cardinal. I encourage you to investi- gate the many activities, museums, galleries, restaurants, and more that Santa Fe has to offer. The Santa Fe Independent Film Festival fills five days with screen- ings, workshops, educational panels, book signings, and celebra- tions. -

LGBT History Month 2016

Inner Temple Library LGBT History Month 2016 ‘The overall aim of LGBT History Month is to promote equality and diversity for the benefit of the public. This is done by: increasing the visibility of lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender (“LGBT”) people, their history, lives and their experiences in the curriculum and culture of educational and other institutions, and the wider community; raising awareness and advancing education on matters affecting the LGBT community; working to make educational and other institutions safe spaces for all LGBT communities; and promoting the welfare of LGBT people, by ensuring that the education system recognises and enables LGBT people to achieve their full potential, so they contribute fully to society and lead fulfilled lives, thus benefiting society as a whole.’ Source: www.lgbthistorymonth.org.uk/about Legal Milestones ‘[A] wallchart has been produced by the Forum for Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity Equality in Further and Higher Education and a group of trade unions in association with Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Trans (LGBT) History Month. The aim has been to produce a resource to support those raising awareness of sexual orientation and gender identity equality and diversity. Centred on the United Kingdom, it highlights important legal milestones and identifies visible and significant contributions made by individuals, groups and particularly the labour movement.’ Source: www.lgbthistorymonth.org.uk/wallchart The wallchart is included in this leaflet, and we have created a timeline of important legal milestones. We have highlighted a selection of material held by the Inner Temple Library that could be used to read about these events in more detail. -

Boys' Love, Byte-Sized

School of Sociology and Social Policy Boys’ Love, Byte-sized: A Qualitative Exploration of Queer- themed Microfiction in Chinese Cyberspace Gareth Shaw B.A. (Hons), M.A. Thesis submitted to the University of Nottingham for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy January 2017 Acknowledgements I owe an enormous debt of gratitude to my supervisors, Dr Xiaoling Zhang, Professor Andrew Kam-Tuck Yip, and Dr Jeremy Taylor, for their constant support and faith in my research. This project would not have been possible without them. I also wish to convey my sincerest thanks to my examiners, Professor Sally Munt and Dr Sarah Dauncey, for their very insightful comments and suggestions, which have been invaluable to this project’s completion. I am grateful to the Economic and Social Research Council for funding this research (Award number: 1228555). I wish to express my heartfelt gratitude to everyone who has participated in this project, particularly to the interview respondents, who gave so freely of their time. I am especially thankful to Huang Guan, Zhai Shunyi and Wei Ye for assisting me with some of the (often quite esoteric) Chinese to English translations. To my family, friends and colleagues, I thank you for being a constant source of comfort and advice when the light at the end of the tunnel seemed to have vanished. Special thanks go to Laura and Céline, for their support and encouragement during the long writing hours. Finally, to Juan and Mani, whose love and support means the world to me, I am eternally grateful to have had you both by my side on this journey. -

SEXUAL ORIENTATION and GENDER IDENTITY October 2, 2019 10336 ICLE: State Bar Series

SEXUAL ORIENTATION AND GENDER IDENTITY October 2, 2019 10336 ICLE: State Bar Series Wednesday, October 2, 2019 SEXUAL ORIENTATION AND GENDER IDENTITY 6 CLE Hours Including | 1 Professionalism Hour Copyright © 2019 by the Institute of Continuing Legal Education of the State Bar of Georgia. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form by any means, electronic, mechanical photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of ICLE. The Institute of Continuing Legal Education’s publications are intended to provide current and accurate information on designated subject matter. They are off ered as an aid to practicing attorneys to help them maintain professional competence with the understanding that the publisher is not rendering legal, accounting, or other professional advice. Attorneys should not rely solely on ICLE publications. Attorneys should research original and current sources of authority and take any other measures that are necessary and appropriate to ensure that they are in compliance with the pertinent rules of professional conduct for their jurisdiction. ICLE gratefully acknowledges the eff orts of the faculty in the preparation of this publication and the presentation of information on their designated subjects at the seminar. The opinions expressed by the faculty in their papers and presentations are their own and do not necessarily refl ect the opinions of the Institute of Continuing Legal Education, its offi cers, or employees. The faculty is not engaged in rendering legal or other professional advice and this publication is not a substitute for the advice of an attorney. -

The Equal Rights Review

The Equal Rights Review Promoting equality as a fundamental human right and a basic principle of social justice In this issue: ■ Special: Detention and discrimination ■ Gender identity jurisprudence in Europe ■ The work of the South African Equality Courts ■ Homophobic discourses in Serbia ■ Testimony from Malaysian mak nyahs The Equal Rights Review Volume Seven (2011) Seven Volume Review Rights The Equal Biannual publication of The Equal Rights Trust Volume Seven (2011) Contents 5 Editorial Detained but Equal Articles 11 Lauri Sivonen Gender Identity Discrimination in European Judicial Discourse 27 Rosaan Krüger Small Steps to Equal Dignity: The Work of the South African Equality Courts 44 Isidora Stakić Homophobia and Hate Speech in Serbian Public Discourse: How Nationalist Myths and Stereotypes Influence Prejudices against the LGBT Minority Special 69 Stefanie Grant Immigration Detention: Some Issues of Inequality 83 Amal de Chickera Draft Guidelines on the Detention of Stateless Persons: An Introductory Note 105 The Equal Rights Trust Guidelines on the Detention of Stateless Persons: Consultation Draft 117 Alice Edwards Measures of First Resort: Alternatives to Immigration Detention in Comparative Perspective Testimony 145 The Mak Nyah of Malaysia: Testimony of Four Transgender Women Interview 157 Equality and Detention: Experts’ Perspectives: ERT talks with Mads Andenas and Wilder Tayler Activities 179 The Equal Rights Trust Advocacy 186 Update on Current ERT Projects 198 ERT Work Itinerary: January – June 2011 4 The Equal Rights -

Nonbinary Gender Identities in Media: an Annotated Bibliography

Nonbinary Gender Identities in Media: An Annotated Bibliography Table of Contents Introduction-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------1 Glossary------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------2 Adult and Young Adult Materials----------------------------------------------------------------------------------6 Nonfiction-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------6 Articles (Scholarly and Popular)------------------------------------------------------------------------14 Fiction---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------19 Comics (Print and Web)----------------------------------------------------------------------------------28 Film and Television----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------31 Web Resources---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------37 Children’s Materials-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------41 Nonfiction----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------41 Fiction---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------41 Film and Television----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------42 -

A Manifesto for Trans Inclusion in the Indian Workplace

A Manifesto for Trans Inclusion in the Indian Workplace BY NAYANIKA NAMBIAR WITH PARMESH SHAHANI December 2018 Research & text: Nayanika Nambiar with Parmesh Shahani Design: Mukta Pai Special thanks: Nisaba Godrej, all our wonderful colleagues at the Culture Lab and Godrej at large especially the D&I, Corporate Communication and GCPL Design teams; and to all those we interviewed for this paper and who shared their thoughts and resources with us so generously 2 Table of Contents I) Introduction and scope of this paper..................................................................................5 II) A manifesto for trans inclusion in the Indian workplace................................................9 PART 1: BACKGROUND: CULTURE, STATE, SOCIETY AND THE LAW................................9 a. What is trans – meaning and cultural background in India.................................................10 b. Legal and social context................................................................................................................13 c. Work on trans inclusion at the state level across India........................................................17 PART 2: THE BUSINESS CASE FOR LGBTQ INCLUSION AT INDIAN COMPANIES...........................................................................................................21 a. LGBTQ inclusion can make you money.....................................................................................22 b. Innovation and talent are found in inclusive workplaces....................................................23 -

Logging Into Horror's Closet

Logging into Horror’s Closet: Gay Fans, the Horror Film and Online Culture Adam Christopher Scales Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of East Anglia School of Art, Media and American Studies September 2015 © This copy of the thesis has been supplied on condition that anyone who consults it is understood to recognise that its copyright rests with the author and that use of any information derived there from must be in accordance with current UK Copyright Law. In addition, any quotation or extract must include full attribution. Abstract Harry Benshoff has boldly proclaimed that ‘horror stories and monster movies, perhaps more than any other genre, actively invoke queer readings’ (1997, p. 6). For Benshoff, gay audiences have forged cultural identifications with the counter-hegemonic figure of the ‘monster queer’ who disrupts the heterosexual status quo. However, beyond identification with the monstrous outsider, there is at present little understanding of the interpretations that gay fans mobilise around different forms and features of horror and the cultural connections they establish with other horror fans online. In addressing this gap, this thesis employs a multi-sited netnographic method to study gay horror fandom. This holistic approach seeks to investigate spaces created by and for gay horror fans, in addition to their presence on a mainstream horror site and a gay online forum. In doing so, this study argues that gay fans forge deep emotional connections with horror that links particular textual features to the construction and articulation of their sexual and fannish identities. In developing the concept of ‘emotional capital’ that establishes intersubjective recognition between gay fans, this thesis argues that this capital is destabilised in much larger spaces of fandom where gay fans perform the successful ‘doing of being’ a horror fan (Hills, 2005). -

A Critical Evaluation of the Rights, Status and Capacity of Distinct Categories of Individuals in Underdeveloped and Emerging Areas of Law

A Critical Evaluation of the Rights, Status and Capacity of Distinct Categories of Individuals in Underdeveloped and Emerging Areas of Law Lesley-Anne Barnes Macfarlane LLB (Hons), Dip LP, PGCE, LLM A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of Edinburgh Napier University, for the award of Doctor of Philosophy May 2014 1 Acknowledgements I would like to express my sincere gratitude to my supervisors, Dr Richard Whitecross and Dr Sandra Watson, for giving me their time, guidance and assistance in the writing up of my PhD Critical Appraisal of published works. I am indebted to my parents, Irene and Dennis, for a lifetime of love and support. Many thanks are also due to my family and friends for their ongoing care and companionship. In particular, I am very grateful to Professors Elaine E Sutherland and John P Grant for reading through and commenting on my section on Traditional Legal Research Methods. My deepest thanks are owed to my husband, Ross, who never fails in his love, encouragement and practical kindness. I confirm that the published work submitted has not been submitted for another award. ………………………………………… Lesley-Anne Barnes Macfarlane Citations and references have been drafted with reference to the University’s Research Degree Reference Guide 2 CONTENTS VOLUME I Abstract: PhD by Published Works Page 8 List of Evidence in Support of Thesis Page 9 Thesis Introduction Page 10 (I) An Era of Change in the Individual’s Rights, Status and Capacity in Scots Law (II) Conceptual Framework of Critical Analysis: Rights, -

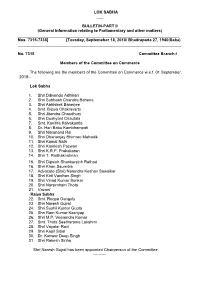

LOK SABHA ___ BULLETIN-PART II (General Information Relating To

LOK SABHA ___ BULLETIN-PART II (General Information relating to Parliamentary and other matters) ________________________________________________________________________ Nos. 7315-7338] [Tuesday, Septemeber 18, 2018/ Bhadrapada 27, 1940(Saka) _________________________________________________________________________ No. 7315 Committee Branch-I Members of the Committee on Commerce The following are the members of the Committee on Commerce w.e.f. 01 September, 2018:- Lok Sabha 1. Shri Dibyendu Adhikari 2. Shri Subhash Chandra Baheria 3. Shri Abhishek Banerjee 4. Smt. Bijoya Chakravarty 5. Shri Jitendra Chaudhury 6. Shri Dushyant Chautala 7. Smt. Kavitha Kalvakuntla 8. Dr. Hari Babu Kambhampati 9. Shri Nityanand Rai 10. Shri Dhananjay Bhimrao Mahadik 11. Shri Kamal Nath 12. Shri Kamlesh Paswan 13. Shri K.R.P. Prabakaran 14. Shri T. Radhakrishnan 15. Shri Dipsinh Shankarsinh Rathod 16. Shri Khan Saumitra 17. Advocate (Shri) Narendra Keshav Sawaikar 18. Shri Kirti Vardhan Singh 19. Shri Vinod Kumar Sonkar 20. Shri Narsimham Thota 21. Vacant Rajya Sabha 22. Smt. Roopa Ganguly 23. Shri Naresh Gujral 24. Shri Sushil Kumar Gupta 25. Shri Ram Kumar Kashyap 26. Shri M.P. Veerendra Kumar 27. Smt. Thota Seetharama Lakshmi 28. Shri Vayalar Ravi 29. Shri Kapil Sibal 30. Dr. Kanwar Deep Singh 31. Shri Rakesh Sinha Shri Naresh Gujral has been appointed Chairperson of the Committee. ---------- No.7316 Committee Branch-I Members of the Committee on Home Affairs The following are the members of the Committee on Home Affairs w.e.f. 01 September, 2018:- Lok Sabha 1. Dr. Sanjeev Kumar Balyan 2. Shri Prem Singh Chandumajra 3. Shri Adhir Ranjan Chowdhury 4. Dr. (Smt.) Kakoli Ghosh Dastidar 5. Shri Ramen Deka 6.