Mckenzie 1 “The Shaft Is in the Stone”: the Emergence of Confederate Memory Through Early Monumentation in South Carolina

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Wine Stroll Sept

THE Inman Park Advocator Atlanta’s Small Town Downtown News • Newsletter of the Inman Park Neighborhood Association September 2017 [email protected] • inmanpark.org • 245 North Highland Avenue NE • Suite 230-401 • Atlanta 30307 Volume 45 • Issue 9 The Wisdom of Our Crowd Springvale Park is on the Mend BY NEIL KINKOPF • [email protected] BY SANDY HOKE • SPRINGVALE PARK COMMITTEE It is offi cial: we live in the weirdest of times. Need proof? [email protected] The weekly Creative Loafi ng is now being printed monthly. It turns out that “News of the Weird” cannot compete with the weirdness of the news. Maybe that is why our President recently returned the nation to Sesame Street for a game of “One of These Things (Is Not Like the Others).” I’m pretty sure even Mr. Noodle wouldn’t be stumped picking the odd man out President’s Message when confronted with Robert E. Lee, Stonewall Jackson, and George Washington. In these troubled and troubling times, perhaps it is wise to shift our focus to our happy place, our comfort zone, our own Sesame Street. For me that’s our neighborhood. Sure, we may be home to an Oscar the Grouch (Chris Coffee, I’m looking at you), and we may have reason to wonder whether Snuffl eupaGrolsch is as benign as he seems. On the whole, though, things here are pretty good. I am especially comfortable that we as a neighborhood care about one another, mostly play nicely together, and clean up even when we didn’t make the mess. -

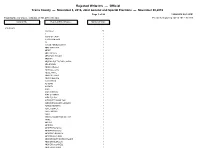

Rejected Write-Ins

Rejected Write-Ins — Official Travis County — November 8, 2016, Joint General and Special Elections — November 08,2016 Page 1 of 28 12/08/2016 02:12 PM Total Number of Voters : 496,044 of 761,470 = 65.14% Precincts Reporting 247 of 268 = 92.16% Contest Title Rejected Write-In Names Number of Votes PRESIDENT <no name> 58 A 2 A BAG OF CRAP 1 A GIANT METEOR 1 AA 1 AARON ABRIEL MORRIS 1 ABBY MANICCIA 1 ABDEF 1 ABE LINCOLN 3 ABRAHAM LINCOLN 3 ABSTAIN 3 ABSTAIN DUE TO BAD CANDIA 1 ADA BROWN 1 ADAM CAROLLA 2 ADAM LEE CATE 1 ADELE WHITE 1 ADOLPH HITLER 2 ADRIAN BELTRE 1 AJANI WHITE 1 AL GORE 1 AL SMITH 1 ALAN 1 ALAN CARSON 1 ALEX OLIVARES 1 ALEX PULIDO 1 ALEXANDER HAMILTON 1 ALEXANDRA BLAKE GILMOUR 1 ALFRED NEWMAN 1 ALICE COOPER 1 ALICE IWINSKI 1 ALIEN 1 AMERICA DESERVES BETTER 1 AMINE 1 AMY IVY 1 ANDREW 1 ANDREW BASAIGO 1 ANDREW BASIAGO 1 ANDREW D BASIAGO 1 ANDREW JACKSON 1 ANDREW MARTIN ERIK BROOKS 1 ANDREW MCMULLIN 1 ANDREW OCONNELL 1 ANDREW W HAMPF 1 Rejected Write-Ins — Official Travis County — November 8, 2016, Joint General and Special Elections — November 08,2016 Page 2 of 28 12/08/2016 02:12 PM Total Number of Voters : 496,044 of 761,470 = 65.14% Precincts Reporting 247 of 268 = 92.16% Contest Title Rejected Write-In Names Number of Votes PRESIDENT Continued.. ANN WU 1 ANNA 1 ANNEMARIE 1 ANONOMOUS 1 ANONYMAS 1 ANONYMOS 1 ANONYMOUS 1 ANTHONY AMATO 1 ANTONIO FIERROS 1 ANYONE ELSE 7 ARI SHAFFIR 1 ARNOLD WEISS 1 ASHLEY MCNEILL 2 ASIKILIZAYE 1 AUSTIN PETERSEN 1 AUSTIN PETERSON 1 AZIZI WESTMILLER 1 B SANDERS 2 BABA BOOEY 1 BARACK OBAMA 5 BARAK -

EXTENSIONS of REMARKS September 11, 1991 EXTENSIONS of REMARKS JOE BARTLETT's MEMORIES of Now Mrs

22684 EXTENSIONS OF REMARKS September 11, 1991 EXTENSIONS OF REMARKS JOE BARTLETT'S MEMORIES OF Now Mrs. Patman had sent word that her Prayer was offered by the Rev. Bernard THE HOUSE son, Bill, a Page in the House, was going Braskamp, a Presbyterian minister with a home to Texas for the month of August and strong Dutch influence. Later, he was to be needed a replacement for that period. The come Chaplain of the House and my very HON. WM. S. BROOMF1EID question being conveyed was, "Would Joe good friend. OF MICHIGAN Bartlett be interested in the appointment?" Visiting in the Gallery that day was Ser IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES Not only was I not prepared for this ques geant York. Not Gary Cooper, but the real Wednesday, September 11, 1991 tion, but my parents were taken completely war hero! He was there to have lunch with aback. They learned it even after everyone the Tennessee delegation, and his congress Mr. BROOMFIELD. Mr. Speaker, some of on our country party line had heard the man made a speech calling for York to be my fellow Members may fondly remember Joe news! made a colonel in the Army, with some none Bartlett, once the minority clerk of the House Sure I was interested! But I did some quick too-kind comparisons to Charles Lindbergh and always a wonderful raconteur with a great calculations, and I did not see how it could who had recently resigned his colonel's com institutional memory. be possible. I told Mrs. Brase I would call her mission in a dispute over preparedness. -

Poets of the South

Poets of the South F.V.N. Painter Poets of the South Table of Contents Poets of the South......................................................................................................................................................1 F.V.N. Painter................................................................................................................................................1 PREFACE......................................................................................................................................................2 CHAPTER I. MINOR POETS OF THE SOUTH.........................................................................................2 CHAPTER II. EDGAR ALLAN POE.........................................................................................................12 CHAPTER III. PAUL HAMILTON HAYNE.............................................................................................18 CHAPTER IV. HENRY TIMROD..............................................................................................................25 CHAPTER V. SIDNEY LANIER...............................................................................................................31 CHAPTER VI. ABRAM J. RYAN..............................................................................................................38 ILLUSTRATIVE SELECTIONS WITH NOTES.......................................................................................45 SELECTION FROM FRANCIS SCOTT KEY...........................................................................................45 -

The Rifle Clubs of Columbia, South Carolina

University of South Carolina Scholar Commons Theses and Dissertations 8-9-2014 Before They Were Red Shirts: The Rifle lubC s of Columbia, South Carolina Andrew Abeyounis University of South Carolina - Columbia Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Abeyounis, A.(2014). Before They Were Red Shirts: The Rifle lC ubs of Columbia, South Carolina. (Master's thesis). Retrieved from https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd/2786 This Open Access Thesis is brought to you by Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Before They Were Red Shirts: The Rifle Clubs of Columbia, South Carolina By Andrew Abeyounis Bachelor of Arts College of William and Mary, 2012 ___________________________________________ Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Master of Arts in Public History College of Arts and Sciences University of South Carolina 2014 Accepted by: Thomas Brown, Director of Thesis Lana Burgess, Reader Lacy Ford, Vice Provost and Dean of Graduate Studies © Copyright by Andrew Abeyounis, 2014 All Rights Reserved. ii DEDICATION This thesis is dedicated to my parents and family who have supported me throughout my time in graduate school. Thank you for reading multiple drafts and encouraging me to complete this project. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS As with every thesis, I would like to thank all the people who helped me finish. I would like to thank my academic advisors including Thomas Brown whose Hist. 800 class provided the foundation for my thesis. -

2010 Arts Advocacy Handbook

2010 ARTS ADVOCACY HANDBOOK Celebrating 30 Years of Service to the Arts January 2010 Dear Arts Leader: As we celebrate our 30th year of service to the arts, we know that “Art Works in South Carolina” – in our classrooms and in our communities. We also know that effective advocacy must take place every day! And there has never been a more important time to advocate for the arts than NOW. With drastic funding reductions to the South Carolina Arts Commission and arts education programs within the S. C. Department of Education, state arts funding has never been more in jeopardy. On February 2nd, the South Carolina Arts Alliance will host Arts Advocacy Day – a special opportunity to celebrate the arts – to gather with colleagues and legislators – and to express support for state funding of the arts and arts education! Meet us at the Statehouse, 1st floor lobby (enter at the Sumter Street side) by 11:30 AM, to pick up one of our ART WORKS IN SOUTH CAROLINA “hard-hats” and advocacy buttons to wear. If you already have a hat or button, please bring them! We’ll greet Legislators as they arrive on the 1st floor and 2nd floors. From the chamber galleries, you can view the arts being recognized on the House and Senate floors. You may want to “call out” your legislator to let him or her know you are at the Statehouse and plan to attend the Legislative Appreciation Luncheon. Then join arts leaders and legislators at the Legislative Appreciation Luncheon honoring the Legislative Arts Caucus. -

South Carolina

Government Relations South Carolina David Wilkins was the long-time Speaker of the South Carolina House of Representatives, until appointed by President George W. Bush to serve as Ambassador to Canada, and is an invaluable resource with his relationships and strategic counsel. He led the transition team for Governor Nikki Haley and serves on the leadership board of the Republican State Leadership Committee (RSLC), which leads GOP efforts in non-federal races. He is joined on the team by Senior Advisor Christy Cox and Special Advisor Ashley Martin Aldebol. David Wilkins Dwight Drake and Ed Poliakoff together have more than 40 years experience lobbying for clients before the South Carolina General Assembly. Mr. Poliakoff is the author of the South Carolina chapter in Lobbying, PACs and Campaign Finance, 50-State Handbook, published annually by Thomson/Reuters. Mr. Drake served as executive assistant for legislative and political affairs for Dwight Drake Governor Richard W. Riley and as legal counsel to Governor John C. West. He has litigated sensitive, high-profile court cases and is recognized as one of the state’s leading political and legislative strategists. George Wolfe was a senior U.S. Treasury Department official during the first term of the Bush Administration and served two tours in the senior leadership of the Coalition Provisional Authority in Iraq. Ed Poliakoff James Burns served as S.C. Gov. Nikki Haley’s chief of staff during the start of her second term and coordinated with legislators and state agencies in carrying out the governor’s agenda. In addition to his experience as the governor’s chief of staff, Mr. -

The Honorable Nikki Haley Governor, State of South Carolina State House, 15T Floor Columbia, South Carolina 29201

ROBERT FORD COMMITTEES: SENATOR, CHARLESTON COUNTY BANKING AND INSURANCE SENATORIAL DISTRICT No. 42 CHAIRPERSON CIVIL RIGHTS AND AFFIRMATIVE ACTION HOME ADDRESS: CORRECTIONS AND PENOLOGY PO. Box 2] 302 JUDICIARY CHARLESTON, SOUTH CAROLINA 29413 LABOR, COMMERCE AND INDUSTRY TELEPHONE: (843) 852-0777 MEDICAL AFFAIRS EMAIL: [email protected] S.c. LEGISLATIVE BLACK CAUCUS WEBSITE: HTTP://SENATORFORD.NET/ INVITATIONS COMMITTEE April 13, 2011 The Honorable Nikki Haley Governor, State of South Carolina State House, 15t Floor Columbia, South Carolina 29201 RE: A Celebration to Put an End to Racial Bitterness in the United States Dear Governor Haley: For you to replace the only African-American on the Medical University of South Carolina (MUSC) Board of Trustees is unbelievable. This action is not accepted by 80% of the state. From April 12, 2011 through April 1, 2015 it is estimated that over two million people will visit South Carolina for the Sesquicentennial celebration & commemoration of the War Between the States. On April 12, 2011, I was at activities at White Pointe Garden. As you know, this is the park adjacent to the Battery. There were thousands of people in attendance to celebrate the 150th anniversary of the War Between the States. Every speaker concluded their remarks by indicating the purpose of the celebration is to unite the south and United States by putting an end to racial bitterness. Governor, you are a part of the smallest minority group ever to be elected Governor, in any state, in United States history. In the general election, led by Maurice Washington of Charleston, South Carolina, several thousand African-Americans, particularly females, voted for you. -

Haley up Big, Sheheen Narrowly in SC Governor Primaries

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE May 25, 2010 INTERVIEWS: DEAN DEBNAM 888-621-6988 / 919-880-4888 (serious media inquiries only please, other questions can be directed to Tom Jensen) QUESTIONS ABOUT THE POLL: TOM JENSEN 919-744-6312 Haley Up Big, Sheheen Narrowly in SC Governor Primaries Raleigh, N.C. – Polled over the weekend, before news broke of possible marital infidelity by gubernatorial candidate Nikki Haley, South Carolina Republicans favor her by a wide margin over her primary opponents to replace outgoing governor Mark Sanford. Meanwhile, Jim Rex and Vincent Sheheen are in a tight battle for the Democratic nomination heading into the June 8th vote. Haley leads at 39%, with the other three contenders grappling for traction in the teens, Henry McMaster at 18, Gresham Barrett at 16, and Andre Bauer at 13. About as many, 14%, are undecided as favor the latter three. Haley and McMaster are both very well liked, with 47-13 and 43-22 favorability marks, while views on Bauer are decidedly negative, at 26-49. Barrett comes in at 28-18. Sheheen tops Rex 36 to 30, with Robert Ford at 11% and 23% still undecided. Over half of Democratic primary voters still have no opinion of Sheheen and Rex, but Sheheen is more popular, with a 31-11 favorability margin to Rex’s 29-19. Sanford still gets a 51% job approval rating among his base electorate, to 36% who disapprove. That is similar to December’s 50-34 margin among all Republican voters. Brought back to the fore with the recent comments by Kentucky Republican Senate nominee Rand Paul, the Civil Rights Act of 1964 is supported by 58% of South Carolina Republican primary voters and opposed by only 15%, with 27% unsure. -

Wardlaw Family

GENEALOGY OF THE WARDLAW FAMILY WITH SOME ACCOUNT OF OTHER FAMILIES WITH WHICH IT IS CONNECTED DATE MICROFILM GENEALOGICAL DEPARTMENT ITEM ON ROLL CAMERA NO CHURCH OF JESUS CHRIST OF LATTER-DAY SAINTS CATALOGUE NO. iKJJr/? 7-/02 ^s<m BY JOSEPH G. WARDLAW EXPLANATION OF CHARACTERS The letters A, B, C, D, E, F, G, H denote the generations beginning with Robert (Al). The large figures indicate the heads of families, or those especially mentioned in their generation. Each generation begins with 1 and continues in regular sequence. The small figures show number, according to birth, in each particular family. Children dying in infancy or early youth are not mentioned again in line with their brothers and sisters. As the work progressed, new material was received, which, in some measure, interfered with the plan above outlined. Many families named in the early generations have been lost in subsequent tracing, no information being available. By a little examination or study of the system, it will be found possible to trace the lineage of any person named in the book, through all generations back to Robert (Al). PREFACE For a number of years I mave been collecting data con cerning the Wardlaw and allied families. The work was un dertaken for my own satisfaction and pleasure, without thought of publication, but others learning of the material in my hands have urged that it be put into book form. I have had access to MSS. of my father and his brothers, Lewis, Frank and Robert, all practically one account, and presumably obtained from their father, James Wardlaw, who in turn doubtless received it from his father, Hugh. -

THE COLLECTED POEMS of HENRIK IBSEN Translated by John Northam

1 THE COLLECTED POEMS OF HENRIK IBSEN Translated by John Northam 2 PREFACE With the exception of a relatively small number of pieces, Ibsen’s copious output as a poet has been little regarded, even in Norway. The English-reading public has been denied access to the whole corpus. That is regrettable, because in it can be traced interesting developments, in style, material and ideas related to the later prose works, and there are several poems, witty, moving, thought provoking, that are attractive in their own right. The earliest poems, written in Grimstad, where Ibsen worked as an assistant to the local apothecary, are what one would expect of a novice. Resignation, Doubt and Hope, Moonlight Voyage on the Sea are, as their titles suggest, exercises in the conventional, introverted melancholy of the unrecognised young poet. Moonlight Mood, To the Star express a yearning for the typically ethereal, unattainable beloved. In The Giant Oak and To Hungary Ibsen exhorts Norway and Hungary to resist the actual and immediate threat of Prussian aggression, but does so in the entirely conventional imagery of the heroic Viking past. From early on, however, signs begin to appear of a more personal and immediate engagement with real life. There is, for instance, a telling juxtaposition of two poems, each of them inspired by a female visitation. It is Over is undeviatingly an exercise in romantic glamour: the poet, wandering by moonlight mid the ruins of a great palace, is visited by the wraith of the noble lady once its occupant; whereupon the ruins are restored to their old splendour. -

Atlanta Heritage Trails 2.3 Miles, Easy–Moderate

4th Edition AtlantaAtlanta WalksWalks 4th Edition AtlantaAtlanta WalksWalks A Comprehensive Guide to Walking, Running, and Bicycling the Area’s Scenic and Historic Locales Ren and Helen Davis Published by PEACHTREE PUBLISHERS 1700 Chattahoochee Avenue Atlanta, Georgia 30318-2112 www.peachtree-online.com Copyright © 1988, 1993, 1998, 2003, 2011 by Render S. Davis and Helen E. Davis All photos © 1998, 2003, 2011 by Render S. Davis and Helen E. Davis All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means—electronic, mechanical, photocopy, recording, or any other—except for brief quotations in printed reviews, without prior permission of the publisher. This book is a revised edition of Atlanta’s Urban Trails.Vol. 1, City Tours.Vol. 2, Country Tours. Atlanta: Susan Hunter Publishing, 1988. Maps by Twin Studios and XNR Productions Book design by Loraine M. Joyner Cover design by Maureen Withee Composition by Robin Sherman Fourth Edition 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Manufactured in August 2011 in Harrisonburg, Virgina, by RR Donnelley & Sons in the United States of America Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Davis, Ren, 1951- Atlanta walks : a comprehensive guide to walking, running, and bicycling the area’s scenic and historic locales / written by Ren and Helen Davis. -- 4th ed. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-1-56145-584-3 (alk. paper) 1. Atlanta (Ga.)--Tours. 2. Atlanta Region (Ga.)--Tours. 3. Walking--Georgia--Atlanta-- Guidebooks. 4. Walking--Georgia--Atlanta Region--Guidebooks. 5.