Thesis , with Minor Corrections Submitted to Research Degrees

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

No. 14 LAGOS- 7Thmarch,1963 Vol. 50

Ed mG i fe a Giooh te No. 14 LAGOS- 7th March,1963 Vol. 50 ‘CONTENTS we. / Page . Page Movethents of Officers - 270-7 Disposal of Unclaimed Firearms i .. 283 Appointment of Acting Chief Justice of the : 3 " Treasury Statements Nos..3-5 . 284-8 : Federation of Nigeria .. 277- List of Registered Contractors—Building, Probate Notice : 278 CivilEngineering and Electrical * 289-319 Delegation of Powers Notice, 1963 .. .. 279 List of Registered Chemists and Druggists 320-29 Grantof PioneerCertificate .. | 279 Paim Oil and Palm Kernels Purchasesiin the Federation of Nigeria 329 Appointment of Parliamentary Secretary 279 Awards for Undergraduate Studies and . Ministry of Communications Notices +279 Technical Training, 1963 .. .. 329-31 Loss ofLocal Purchase Orders,etc. 279-81 University of Nigeria—Applications for ss Admission 1963-4 . 331 Cancellation of Certificate of Registration of Trade Unions. 281 Tenders . tees . «. 332-3 Licensed Commercial Banks’ Analysisof . “Vacancies «» 333-9 Loans and Advances . 281 UNESCO Vacancies .. oe «awe 83339 Lagos Consumer Price Index—Lower Income Group - -. 281 -3 Board of Customs and Excise Sales Notices 339-40 Lagos Consumer Price Index—Middle . ' Application to operate ScheduledAir Services Income Group* . 282 340 ~ ‘Training of Nigerians as Commercial Pilots 282 Inpex To Lecan Notices n SUPPLEMENT ‘Teachers’ Grade III Certificate Examination, . 1956—-Supplementary Pass List -. 283 LN. No. Short Title Page Teachers’ Grade .II Certificate Examination, 983 - 27 Tin (Research tevy) Regulations, -1956—Supplementary Pass List — , : 1963 . os -- B73 270 (OFFICIAL ‘GAZETTE No. 14, Vol. 50 Guzernment Notice No, 429 + ~ NEW APPOINTMENTS AND OTHER STAFF CHANGES The following are notified for general information :— NEWAPPOINTMENTS Tv Depariment Name Appointment Date of Date of, Appointment Arrival Administration Adelaja, A. -

Othering Terrorism: a Rhetorical Strategy of Strategic Labeling

Genocide Studies and Prevention: An International Journal Volume 13 Issue 2 Rethinking Genocide, Mass Atrocities, and Political Violence in Africa: New Directions, Article 9 New Inquiries, and Global Perspectives 6-2019 Othering Terrorism: A Rhetorical Strategy of Strategic Labeling Michael Loadenthal Miami University of Oxford Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/gsp Recommended Citation Loadenthal, Michael (2019) "Othering Terrorism: A Rhetorical Strategy of Strategic Labeling," Genocide Studies and Prevention: An International Journal: Vol. 13: Iss. 2: 74-105. DOI: https://doi.org/10.5038/1911-9933.13.2.1704 Available at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/gsp/vol13/iss2/9 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Open Access Journals at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Genocide Studies and Prevention: An International Journal by an authorized editor of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Othering Terrorism: A Rhetorical Strategy of Strategic Labeling Michael Loadenthal Miami University of Oxford Oxford, Ohio, USA Reel Bad Africans1 & the Cinema of Terrorism Throughout Ridley Scott’s 2002 film Black Hawk Down, Orientalist “othering” abounds, mirroring the simplistic political narrative of the film at large. In this tired script, we (the West) are fighting to help them (the East Africans) escape the grip of warlordism, tribalism, and failed states through the deployment of brute counterinsurgency and policing strategies. In the film, the US soldiers enter the hostile zone of Mogadishu, Somalia, while attempting to arrest the very militia leaders thought to be benefitting from the disorder of armed conflict. -

Assessment of States' Response to the September

i ASSESSMENT OF STATES’ RESPONSE TO THE SEPTEMBER 11, 2001TERROR ATTACK IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA AND THE NIGERIAN PERSPECTIVE BY EMEKA C. ADIBE REG NO: PG/Ph.D/13/66801 UNIVERSITY OF NIGERIA FACULTY OF LAW DEPARMENT OF INTERNATIONAL LAW AND JURISPRUDENCE AUGUST, 2018 ii TITLE PAGE ASSESSMENT OF STATES’ RESPONSETO THE SEPTEMBER 11, 2001TERROR ATTACK IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA AND THE NIGERIAN PERSPECTIVE BY EMEKA C. ADIBE REG. NO: PG/Ph.D/13/66801 SUBMITTED IN FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE AWARD OF THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN LAW IN THE DEPARMENT OF INTERNATIONAL LAW AND JURISPRUDENCE, FACULTY OF LAW, UNIVERSITY OF NIGERIA SUPERVISOR: PROF JOY NGOZI EZEILO (OON) AUGUST, 2018 iii CERTIFICATION This is to certify that this research was carried out by Emeka C. Adibe, a post graduate student in Department of International law and Jurisprudence with registration number PG/Ph.D/13/66801. This work is original and has not been submitted in part or full for the award of any degree in this or any other institution. ---------------------------------- ------------------------------- ADIBE, Emeka C. Date (Student) --------------------------------- ------------------------------- Prof. Joy Ngozi Ezeilo (OON) Date (Supervisor) ------------------------------- ------------------------------- Dr. Emmanuel Onyeabor Date (Head of Department) ------------------------------------- ------------------------------- Prof. Joy Ngozi Ezeilo (OON) Date (Dean, Faculty of Law) iv DEDICATION To all Victims of Terrorism all over the World. v ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Gratitude is owned to God in and out of season and especially on the completion of such a project as this, bearing in mind that a Ph.D. research is a preserve of only those privileged by God who alone makes it possible by his gift of good health, perseverance and analytic skills. -

The Impact of Transportation Infrastructure on Nigeria's Economic Developmeny

Walden University ScholarWorks Walden Dissertations and Doctoral Studies Walden Dissertations and Doctoral Studies Collection 2016 The mpI act of Transportation Infrastructure on Nigeria's Economic Developmeny William A. Agbigbe Walden University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.waldenu.edu/dissertations Part of the Business Administration, Management, and Operations Commons, Databases and Information Systems Commons, and the Management Sciences and Quantitative Methods Commons This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Walden Dissertations and Doctoral Studies Collection at ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Walden Dissertations and Doctoral Studies by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Walden University College of Management and Technology This is to certify that the doctoral dissertation by William A. Agbigbe Sr. has been found to be complete and satisfactory in all respects, and that any and all revisions required by the review committee have been made. Review Committee Dr. Robert DeYoung, Committee Chairperson, Management Faculty Dr. Godwin Igein, Committee Member, Management Faculty Dr. Salvatore Sinatra, University Reviewer, Management Faculty Chief Academic Officer Eric Riedel, Ph.D. Walden University 2016 Abstract The Impact of Transportation Infrastructure on Nigeria’s Economic Development by William A. Agbigbe, Sr. MA, Southern Illinois University, 1981 BSBA, University of Missouri, 1976 Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Management Walden University August 2016 Abstract The United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) described Nigeria’s road networks as one of the poorest and deadliest transportation infrastructural systems in the world. -

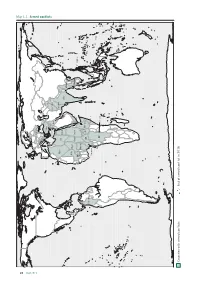

Armed Conflicts

Map 22 1 . 1. Armed conicts Ukraine Turkey Syria Palestine Afghanistan Iraq Israel Algeria Pakistan Libya Egypt India Myanmar Mali Niger Chad Sudan Thailand Yemen Burkina Philippines Faso Nigeria South Ethiopia CAR Sudan Colombia Somalia Cameroon DRC Burundi Countries with armed conflicts End2018 of armed conflict in Alert 2019 1. Armed conflicts • 34 armed conflicts were reported in 2018, 33 of them remained active at end of the year. Most of the conflicts occurred in Africa (16), followed by Asia (nine), the Middle East (six), Europe (two) and America (one). • The violence affecting Cameroon’s English-speaking majority regions since 2016 escalated during the year, becoming a war scenario with serious consequences for the civilian population. • In an atmosphere characterised by systematic ceasefire violations and the imposition of international sanctions, South Sudan reached a new peace agreement, though there was scepticism about its viability. • The increase and spread of violence in the CAR plunged it into the third most serious humanitarian crisis in the world, according to the United Nations. • The situation in Colombia deteriorated as a result of the fragility of the peace process and the finalisation of the ceasefire agreement between the government and the ELN guerrilla group. • High-intensity violence persisted in Afghanistan, but significant progress was made in the exploratory peace process. • The levels of violence in southern Thailand were the lowest since the conflict began in 2004. • There were less deaths linked to the conflict with the PKK in Turkey, but repression continued against Kurdish civilians and the risk of destabilisation grew due to the repercussions of the conflict in Syria. -

Examining the Boko Haram Insurgency in Northern

Global Journal of Arts, Humanities and Social Sciences Vol.3, No.8, pp.32-45, August 2015 ___Published by European Centre for Research Training and Development UK (www.eajournals.org) EXAMINING THE BOKO HARAM INSURGENCY IN NORTHERN NIGERIA AND THE QUEST FOR A PERMANENT RESOLUTION OF THE CRISIS Joseph Olukayode Akinbi (Ph.D) Department of History, Adeyemi Federal University of Education P.M.B 520, Ondo, Ondo State, Nigeria ABSTRACT: The state of insecurity engendered by Boko Haram insurgency in Nigeria, especially in the North-Eastern part of the country is quiet worrisome, disheartening and alarming. Terrorist attacks of the Boko Haram sect have resulted in the killing of countless number of innocent people and wanton destruction of properties that worth billions of naira through bombings. More worrisome however, is the fact that all the efforts of the Nigerian government to curtail the activities of the sect have not yielded any meaningful positive result. Thus, the Boko Haram scourge remains intractable to the government who appears helpless in curtailing/curbing their activities. The dynamics and sophistication of the Boko Haram operations have raised fundamental questions about national security, governance issue and Nigeria’s corporate existence. The major thrust of this paper is to investigate the Boko Haram insurgency in Northern Nigeria and to underscore the urgent need for a permanent resolution of the crisis. The paper argues that most of the circumstances that led to this insurgency are not unconnected with frustration caused by high rate of poverty, unemployment, weak governance, religious fanaticism among others. It also addresses the effects of the insurgency which among others include serious threat to national interest, peace and security, internal population displacement, violation of fundamental human rights, debilitating effects on the entrenchment of democratic principles in Nigeria among others. -

The Age of Hyperconflict and the Globalization-Terrorism Nexus: a Comparative Study of Al Shabaab in Somalia and Boko Haram in Nigeria

The Age of Hyperconflict and the Globalization-Terrorism Nexus: A Comparative Study of Al Shabaab in Somalia and Boko Haram in Nigeria By Vasti Botma Thesis presented in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts (Political Science) in the Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences at Stellenbosch University Supervisor: Mr. Gerrie Swart December 2015 The financial assistance of the National Research Foundation (NRF) towards this research is hereby acknowledged. Opinions expressed and conclusions arrived at, are those of the author and are not necessarily to be attributed to the NRF. Stellenbosch University https://scholar.sun.ac.za Declaration By submitting this thesis electronically, I declare that the entirety of the work contained therein is my own original work, that I am the authorship owner thereof (unless to the extent explicitly otherwise stated) and that I have not previously in its entirety or in part submitted it for obtaining any qualification. December 2015 Copyright © 2015 Stellenbosch University of Stellenbosch All rights reserved i Stellenbosch University https://scholar.sun.ac.za Abstract Globalization has radically changed the world we live in; it has enabled the easy movement of people, goods and money across borders, and has facilitated improved communication. In a sense it has made our lives easier, however the same facets that have improved the lives of citizens across the globe now threatens them. Terrorist organizations now make use of these same facets of globalization in order to facilitate terrorist activity. This thesis set out to examine the extent to which globalization has contributed to the creation of a permissive environment in which terrorism has flourished in Somalia and northern Nigeria respectively, and how it has done so. -

Role of Transportation and Marketing in Enhancing Agricultural Production in Ikwo Local Government Area of Ebonyi State, Nigeria

Sustainability, Agri, Food and Environmental Research, (ISSN: 0719-3726), 6(4), 2018: 22-39 22 http://dx.doi.org/10.7770/safer-V0N0-art1353 ROLE OF TRANSPORTATION AND MARKETING IN ENHANCING AGRICULTURAL PRODUCTION IN IKWO LOCAL GOVERNMENT AREA OF EBONYI STATE, NIGERIA. ROL DEL TRANSPORTE Y MERCADO EN ESTIMULACIÓN DE LA PRODUCCIÓN AGRICOLA EN EL GOBIERNO LOCAL DEL AREA DEL ESTADO DE EBONYI, NIGERIA. Ume Smiles Ifeanyichukwu*, K.O. knadosie, C Kadurumba Agricultural Extension and Management.Federal College of Agriculture Ishiagu, Ebonyi State, Nigeria. Department of Agricultural Economics and Extension, Nnamdi Azikiwe University, Awka, Anambra State, Nigeria. * Corresponding Author; [email protected] ABSTRACT Role of transport and marketing in enhancing agricultural production in Ikwo Local Government Area of Ebonyi State, Nigeria was studied. A multi stage sampling procedure was used to select 300 respondents for the detailed study. A structured questionnaire was used to elicit information from the respondents. Data collected were analyzed using of chi-square. The results show that head carrying, use of wheel barrows, bicycles, motor van, keke, donkeys, and motor cycles were various traditional modes of transportation for inter local transport of agricultural products. Furthermore, the result reveals that producers, retailers, consumers, wholesalers and processors were the marketing channels in the study area. Additionally, transportation and marketing have greatly enhanced the growth of agricultural production in the study area, despite existing problems such as bad roads, high cost of transport, few vehicles, poor drainage channels, culverts, few bridges and poverty. Also, the solutions to the identified problems were giving out loans to farmers, construction and repairs of roads, use of rail, mass transit, encouraging farmers’ cooperative societies and processing centres. -

Fragility and Climate Risks in Nigeria

FRAGILITY AND CLIMATE RISKS IN NIGERIA SEPTEMBER 2018 This publication was produced for review by the United States Agency for International Development. It was prepared by Ashley Moran, Clionadh Raleigh, Joshua W. Busby, Charles Wight, and Management Systems International, A Tetra Tech Company. FRAGILITY AND CLIMATE RISKS IN NIGERIA Contracted under IQC No. AID-OAA-I-13-00042; Task Order No. AID-OAA-TO-14-00022 Fragility and Conflict Technical and Research Services (FACTRS) DISCLAIMER The author’s views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views of the United States Agency for International Development or the United States Government. TABLE OF CONTENTS Acronyms...................................................................................................................... iv Executive Summary ...................................................................................................... 1 Introduction ................................................................................................................... 3 Climate Risks ................................................................................................................. 3 Fragility Risks ................................................................................................................. 7 Key Areas of Concern ........................................................................................................................ 8 Key Area of Improvement ................................................................................................................ -

Genocide Or Terrorism?

Genocide Studies and Prevention: An International Journal Volume 13 Issue 2 Rethinking Genocide, Mass Atrocities, and Political Violence in Africa: New Directions, Article 2 New Inquiries, and Global Perspectives 6-2019 Full Issue 13.2 Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/gsp Recommended Citation (2019) "Full Issue 13.2," Genocide Studies and Prevention: An International Journal: Vol. 13: Iss. 2: 1-173. DOI: https://doi.org/10.5038/1911-9933.13.2 Available at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/gsp/vol13/iss2/2 This Front Matter is brought to you for free and open access by the Open Access Journals at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Genocide Studies and Prevention: An International Journal by an authorized editor of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ISSN 1911-0359 eISSN 1911-9933 Genocide Studies and Prevention: An International Journal Volume 13.2 - 2019 ii ©2019 Genocide Studies and Prevention 13, no. 2 iii Genocide Studies and Prevention: An International Journal http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/gsp/ Volume 13.2 - 2019 Editorials Christian Gudehus, Susan Braden, Douglas Irvin-Erickson, JoAnn DiGeorgio-Lutz, Lior Zylberman, Fiza Lee, and Brian Kritz Editors’ Introduction ................................................................................................................1 Laura Collins Guest Editorial: Rethinking Genocide, Mass Atrocities, and Political Violence in Africa .......2 State of the Field Terrence Lyons Transnational Advocacy: -

Extremism & Terrorism

Chad: Extremism & Terrorism On April 20, 2021, President Idriss Deby—Chad’s president for more than 30 years—died due to injuries sustained in battle fighting against the Libya-based Islamist rebel group, Front for Change and Concord in Chad (FACT), in northern Chad. Deby, who was declared the winner of the presidential election the day prior, often joined soldiers on the battlefront. On April 11, 2021, hundreds of FACT forces launched an incursion into the north of Chad to protest the April 11th presidential election. The group attacked a border post at Zouarke. However, no casualties were reported. Following the Zouarke ambush, Deby joined Chadian soldiers to repel FACT forces from advancing on N’Djamena. On April 17, two FACT convoys clashed with government forces on the way to N’Djamena, killing five Chadian soldiers and injuring 36 others. Among those injured was Deby. Deby’s son, Mahamat Kaka, was named interim president by a transitional council of military officers on April 20. (Sources: Reuters, France 24, Al Jazeera, Reuters, Bloomberg) On February 15, 2021, leaders of the G5 Sahel—Chad, Burkina Faso, Mali, Mauritania, and Niger—attended a two-day summit in N’Djamena. At the summit, Deby announced that more than 1,200 troops would be deployed to combat extremist groups on the Sahel border zone between Niger, Mali, and Burkina Faso. Deby urged the international community to increase its funds for development to prevent the continued rise of terrorism and reasons for radicalization in Chad. Chad’s increase in deployment comes a month after French President Emmanuel Macron suggested that France may “adjust” its military commitment in the Sahel following attacks that increased the number of French combat deaths to 50 in Mali. -

The Third Wave of Historical Scholarship on Nigeria

CHAPTER ONE THE THIRD WAVE OF HISTORICAL SCHOLARSHIP ON NIGERIA SAHEED ADERINTO AND PAUL OSIFODUNRIN The significant place of Nigeria in Africanist studies is indisputable— it is one of the birthplaces of academic historical research on Africa. Nigeria is also one of the most studied countries in Africa.1 Academic writings on the country date back to the 1950s when scholars at the University College Ibadan (later the University of Ibadan) launched serious investigations into the nation’s precolonial and colonial past. The ideology of this first wave of academic history was well laid out—guarded and propagated from the 1950s through the 1970s. Scholars were convinced that research into the precolonial histories of state and empire formation and the sophistication of political structures before the advent of imperialism would supply the evidence needed to counteract the notion— obnoxious to Africans—that they needed external political overlords because of their inability to govern themselves. Historical research was therefore pivoted toward restoring Nigerian peoples into history. This brand of academic tradition, widely called “nationalist historiography,” supplied the much needed ideological tools for decolonization through its deployment of oral history, archaeology, and linguistic evidence. But like any school of thought, nationalist historiography had to adapt to new ideas and respond to changing events; unfortunately its failure to reshape its research agenda and inability to reinvent itself, coupled with several developments outside academia, made it an anachronism and set in motion its demise from the 1980s or earlier.2 However, the story of nationalist historiography transcends its “rise” and “fall.” Indeed, without nationalist historiography, historical research Copyright © 2012.