Examining Differences Among Private Schools in British Columbia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cowichan Valley Regional District Sport Hosting Resume

Cowichan Valley Regional District Sport Hosting Resume Cowichan Valley’s enthusiastic sports communities have a proud and very successful history of hosting significant sporting and cultural events, including the 2005 BC Seniors Games and the 2008 North American Indigenous Games, (which have been recognized as the most successful NAIG games ever held) and the 2018 BC Summer Games. Our support of sport events also includes hosting many annual hockey, curling, and golf tournaments. A few of our hosting achievements: 2018 Rogers Hometown Hockey 2018 Men’s Amateur Golf Championship 2008 Senior Women Provincial Curling 2018 BC Summer Games Championships 2018 Box Lacrosse Provincial Championships 2007 Juvenile Provincial Curling Championships 2017 Traveller’s Club South Island Curling 2007 High School Rugby Provincials Challenge 2006 U18 Girls National Field Hockey 2017 National Aboriginal Hockey Championships Championships 2017 BC Scotties Tournament of Hearts 2005 BC Seniors Games 2017 Can Am Ex Rowing Regatta 2016 BC Hockey Female Invitational Selection Annual: Camp Lake to Lake Walk and Marathon 2015 Juvenile Curling Provincial Championships Road and Mountain Cycling Competitions 2014 International Curling Tankard Windfest Windsurfing Festival 2013-2016 Jr. Girls Basketball Provincial Equestrian Shows and Competitions Championships Maple Bay Rowing Regatta 2013 Provincial Wrestling Championships Shawnigan Lake School Rowing Regatta 2013 Provincial Masters Curling Championships Brentwood International Rowing Regatta 2013 Female U16 Hockey -

December 2015 Issue 215 Federation of Independent School Associations in British Federation of Independent School Associations in British Columbia Columbia

December 2015 Issue 215 Federation of Independent School Associations in British Federation of Independent School Associations in British Columbia Columbia Contact Information Website: www.fisabc.ca Email: Coming Soon: Convention 2016! [email protected] FISA BC’s mission is to protect parents’ right to With over 5000 delegates in attendance, we Address: choose the kind of education given to their recommend that each participant select the 4885 St. John Paul II Way children, and to safeguard the autonomy of Session Speakers and Ed Talks from the web- independent schools. FISA BC was formed in site at www.fisabc-convention2016.com/ that Vancouver, BC 1966 after extensive discussion among the di- are of most interest and to be sure to arrive at V5Z 0G3 verse independent schools in BC. Eleven years the selected rooms well in advance of the be- of subsequent political action resulted in 30% ginning of the relevant sessions. Due to the Telephone: funding for operations in 1977. The Sullivan large number of delegates at the Convention 604-684-6023 Commission in 1989 increased government we are unable to offer preregistration for funding from 30% of operating costs to 50% for these sessions, so seating will be awarded on a Executive Director: Group 1 schools and 35% for Group 2 schools. first come, first served basis. Peter Froese In the intervening years, FISA BC has protected independent schools from erosion of govern- We would like to take this opportunity to ex- Executive Assistant: ment funding, procured full funding for special press appreciation to the individuals and com- Magda Hogewoning needs students, initiated Distance Learning, panies that have chosen to support Conven- and strengthened statutory property tax ex- tion 2016 financially and/or contribute door emption for independent schools. -

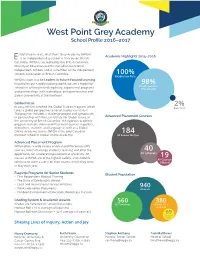

West Point Grey Academy School Profile 2016–2017

West Point Grey Academy School Profile 2016–2017 stablished in 1996, West Point Grey Academy (WPGA) Academic Highlights 2015–2016 E is an independent day school in Vancouver, British Columbia. WPGA is accredited by the British Columbia Ministry of Education and the Canadian Accredited Independent Schools and is a member of the Independent Schools Association of British Columbia. raduation Rate WPGA’s vision is to be Leaders in Future-Focused Learning. Inspired by our rapidly evolving world, we are a model for ostsecondary schools in offering interdisciplinary, experiential programs lacements and partnerships, with technology, entrepreneurship and global connectivity at the forefront. Global Focus In 2014, WPGA launched the Global Studies Program, which ap ear takes a global perspective to social studies curriculum. The program includes a challenge project and symposium in partnership with the Liu Institute for Global Issues at Advanced Placement Courses the University of British Columbia; the rigorous academic program includes Advanced Placement courses in politics, economics, statistics and language as well as a Global Online Academy course (WPGA is the only Canadian 184 member school in Global Online Academy). A ams ritten Advanced Placement Program WPGA offers a wide variety of Advanced Placement (AP) courses, which challenge students’ learning and offer the 40 opportunity for accelerated placement at university. AP A Scholars classes at WPGA are of the highest calibre, and students continue to score a 4 or 5 on their exams, which they write in May each year. Flagship Programs for Senior Students Student Population • First Responders Medical Training • The Duke of Edinburgh’s Award • Local and International Service Initiatives • Work Experience Placements Students • Outdoor Environmental Education; Wilderness Pursuits Grading System & Academic Awards 560 380 Grades are reflected on school transcripts. -

Curriculum Vitae RONALD W. MARX

Curriculum Vitae RONALD W. MARX CONTACT INFORMATION Office College of Education University of Arizona 1430 E. 2nd Street PO Box 210069 Tucson, AZ 85721-0069 (520) 621-9640 (office) (520) 205-0404 (mobile) DEGREES Stanford University 1978 Ph.D, Educational Psychology and Child Development California State University, Northridge 1971 M.A., School Psychology California State University, Northridge 1969 B.A. (cum laude), Psychology CERTIFICATION State of California Life Credential, Pupil Personnel Services: School Psychology Community College Teaching Credential: Psychology Province of British Columbia Licensed Psychologist (lapsed) -2- 2 PROFESSIONAL EMPLOYMENT 2017- Professor of Educational Psychology Dean Emeritus University of Arizona 2003-2017 Dean Professor of Educational Psychology Paul L. Lindsey and Kathy J. Alexander Chair in Education University of Arizona 1990-2003 Professor, Educational Studies Program, School of Education University of Michigan 1984-1990 Professor 1983-1987 Director of Graduate Programs 1979-1988 Senior Researcher, Instructional Psychology Research Group 1979-1984 Associate Professor 1975-1979 Assistant Professor Faculty of Education, Simon Fraser University Burnaby, British Columbia 1987-1988 Director of Research Learner's Group, British Columbia Royal Commission on Education 1982-1983 Visiting Scholar Department of Educational Psychology, University of Arizona 1977, 1979 , 1980, 1981 (Summers) Visiting Member Department of Educational Psychology, Faculty of Education University of British Columbia 1975 Teaching -

2020 Beaver Computing Challenge Results

2020 Beaver Computing Challenge Results Statistics Overall Statistics for Grade 5/6 Number of competitors: 4727 Overall average score: 44.51 Standard deviation: 13.44 Overall percentage score: 74.18 Averages by question Bear Selection: 5.72/6 Moving Packages: 2.75/5 Museum Tour: 2.90/4 Bowls: 4.44/6 Skyline: 3.03/5 Weighing Boxes: 2.83/4 Bird Watching: 4.73/6 Market Exchange: 3.94/5 Jumping Kangaroo: 3.17/4 Rare Mushrooms: 4.55/6 Beaver Homes: 4.00/5 Theatre Performance: 2.58/4 2 Statistics Overall Statistics for Grade 7/8 Number of competitors: 6368 Overall average score: 64.18 Standard deviation: 15.93 Overall percentage score: 71.31 Averages by question Skyline: 5.69/8 Library Books: 4.25/6 Spider Car: 1.88/4 Crypto Keys: 7.66/8 Market Exchange: 5.39/6 Puzzle Pieces: 2.83/4 Cookies: 7.61/8 House Painting: 4.02/6 Spreading the News: 1.34/4 Connect the Dots: 6.20/8 Treasure Hunt: 4.65/6 Book Organizer: 3.18/4 Towns and Highways: 2.37/8 Water Bottles: 4.48/6 Train Trip: 2.72/4 3 Statistics Overall Statistics for Grade 9/10 Number of competitors: 4373 Overall average score: 60.65 Standard deviation: 16.13 Overall percentage score: 67.39 Averages by question Skyline: 6.49/8 Beaver Intelligence Agency: 3.19/6 Craft: 0.48/4 Library Books: 6.08/8 Mountain Climber: 3.27/6 Vegetable Shipment: 2.05/4 Locked Chests: 6.39/8 Image Scanner: 4.21/6 DNA Sequence: 2.07/4 Water Bottles: 6.48/8 Household Appliances: 4.37/6 Mixed Results: 1.97/4 Ancient Texts: 7.56/8 Puzzle Pieces: 4.67/6 Nine Marbles: 1.52/4 4 Honour Roll for Grade 5/6 Each section is sorted by Last Name. -

2019 BCSS AGM Package 2!.Pdf

April 26th - 27th, 2019 BCWhistler, SCHOOL British Columbia SPORTS Annual General Meeting Kelowna, British Columbia MEETING PACKAGE 2 April 2019 The Cove Lakeside Resort Kelowna, BC General Information The Cove Lakeside Resort - West Kelowna Hotel Information The Cove Lakeside Resort is located on the western shore of Okanagan Lake. The Resort features elegantly decorated rooms, stunning views and comfortable in-room amenities. If you have booked a room through BCSS, you will have received a confi rmation email from Karen Hum, please check to make sure the reservation information is correct. Things to do in Kelowna • Visit a Winery - Quail’s Gate Winery & Mission Hill Family Estate Winery are a short distance to from the hotel • Visit Bear Creek Provincial Park - A beautiful Provincial Park on the west side of Okanagan Lake • Relax at Lake Okanagan - Can you spot the Ogopogo? • Enjoy a Round of Golf - Test your skills at one of Kelowna’s 19 exceptional courses • Shopping - Kelowna’s downtown shopping core has a blend of retail shops, galleries, and boutiques to explore. Transportation The Cove Lakeside Resort is located at: 4205 Gellatly Road West Kelowna, BC V4T 2K2 Airport Kelowna International Airport has frequent fl ights in and out daily from around the province. It is a short trip from the Airport to the Resort. If you will be fl ying in to the AGM please let us know and we can help with arrangements for transportation to the hotel. Distance to and from the airport is 29km and approximately 25-40 minutes. Kelowna Weather Kelowna’s weather this time of year ranges from: Average Daily High: 15°C Average Daily Low: 3°C Please keep an eye on the weather closer to the AGM, and pack accordingly. -

Post-Secondary Planning Guide 2020-2021 Changing Destiny by Changing Minds Contents

POST-SECONDARY PLANNING GUIDE 2020-2021 CHANGING DESTINY BY CHANGING MINDS CONTENTS About this Guidebook 02 Graduation Requirements 03 What is the Career Life Connections Program? 04 Current University and College Operations Amid COVID-19 06 Application and Admission Procedures Summary 2020-21 08 Accessibility Services at Post-Secondary Institutions 10 Psychological-Educational Assessments and Post-Secondary Education 11 Self-Advocacy 12 Post-Secondary Checklist for Students with Learning Differences 13 Post-Secondary Education Institutions 14 Volunteer and Travel Programs 22 General Information on Scholarships, Awards, and Financial Aid 24 Canadian Bursaries for Students with Disabilities 26 © Fraser Academy ABOUT THIS GUIDEBOOK This booklet contains important information for your son or daughter’s final year at Fraser Academy. All information is accurate as of September 2020. For those students wanting to attend post-secondary institutions, the program options are practically limitless. As each student has unique needs, preferences and circumstances, finding a good fit is the result of teamwork (student, plus his or her family, teachers and counsellors). Each institution has its own application opening and deadline dates, as well as documentation requirements. Check each individual school online for the most up-to-date information. Please note that admission averages are re-calculated every year, which is often based on the applicant pool for that year. There are also many options for those students taking a year off, including volunteering, working or travelling in Canada or another country. The Post-Secondary Planning Team can help students work on their resume or interviewing skills, and offer information about GAP and other programs. -

ISEA Championships Results

ISEA BC May 22, 2018 OFFICIAL MEET REPORT printed: 2018-05-22 8:27 PM RESULTS #6 Girls 60 Meters (4th Grade A) Pl Name Team Time Note H(Pl) Pts 1 JIANG, Selina Southridge School 9.71 (NW) 2(1) 10 2 WANG, Ann West Point Grey Academy 9.77 (NW) 1(1) 8 3 JEKUBIK, Emily York House School 9.86 (NW) 1(2) 6 4 WAN, Chloe Stratford Hall School 10.33 (NW) 2(2) 5 5 WESTERINGH, Eva Southpointe Academy 10.34 (NW) 2(3) 4 6 MCDONALD, Kate Crofton House School 10.38 (NW) 1(3) 3 7 ALEKSON, Lauren BPS 10.63 (NW) 2(4) 2 8 LINTS, Emily St. John's School 10.88 (NW) 1(4) 1 9 COHEN, Joelle Collingwood School 11.14 (NW) 1(5) 10 ZHOU, Jasmine Meadowridge School 11.59 (NW) 2(5) 11 SHU, Sophie Urban Academy Lions 13.10 (NW) 2(6) SECTION RESULTS Pl Name Team Time Note Section 1 of 2 Wind: (NW) 1 WANG, Ann West Point Grey Academy 9.77 2 JEKUBIK, Emily York House School 9.86 3 MCDONALD, Kate Crofton House School 10.38 4 LINTS, Emily St. John's School 10.88 5 COHEN, Joelle Collingwood School 11.14 Section 2 of 2 Wind: (NW) 1 JIANG, Selina Southridge School 9.71 2 WAN, Chloe Stratford Hall School 10.33 3 WESTERINGH, Eva Southpointe Academy 10.34 4 ALEKSON, Lauren BPS 10.63 5 ZHOU, Jasmine Meadowridge School 11.59 6 SHU, Sophie Urban Academy Lions 13.10 #7 Girls 60 Meters (4th Grade B) Pl Name Team Time Note H(Pl) Pts 1 MILAU, Rachel West Point Grey Academy 9.33 (NW) 2(1) 10 2 HU, Elgina Southridge School 10.02 (NW) 1(1) 8 3 CHAN, Olivia Crofton House School 10.38 (NW) 2(2) 6 4 STEWART, Campbell BPS 10.57 (NW) 1(2) 5 5 SOON, Makaella Stratford Hall School 10.64 (NW) 1(3) 4 6 HERAS , Emma Southpointe Academy 10.71 (NW) 1(4) 3 7 GORDON, Grace York House School 10.76 (NW) 2(3) 2 8 HUTCHINSON, Cecilia Meadowridge School 10.82 (NW) 2(4) 1 9 HUANG, Eva St. -

Head of School Opportunity

HEAD OF SCHOOL OPPORTUNITY WELCOMEWELCOME Founded in 1917, Vancouver Talmud Torah (VTT) is Canada’s largest elementary Jewish day school west of Toronto, serving more than 200 families and 440 students in preschool 3 through grade 7. VTT is an inclusive Jewish day school rooted in Jewish traditions, values and knowledge, and infused with the spirit of chesed and tikkun olam. VTT serves a socially, economically, religiously and academically diverse community through a robust dual-track general and Judaic studies curriculum built upon the principles of 21st century learning. Students are welcomed into a warm, supportive and innovative learning environment, rich with extra-curricular, performing arts, athletic and Jewish values-based programming. MISSION Vancouver Talmud Torah is an inclusive Jewish community day school committed to academic excellence and nurturing lifelong learners who engage the world through Jewish traditions and values. To learn more about VTT’s values, please click here. VISION Families in Greater Vancouver will recognize VTT as the premiere Jewish day school for students from a broad spectrum of Jewish practice and belief. The Jewish community in Vancouver will recognize VTT as a partner in educating Jewish students and an integral part of the fabric of Jewish life in the community. The Greater Vancouver community will recognize the active role VTT plays as a contributor to social justice in the community, across Canada, and around the world. THE OPPORTUNITY VTT presents an exceptional leadership opportunity for the next Head of School. VTT’s next leader will arrive at a particularly exciting time as the school completes the first year of its second century and prepares to appoint its first new HOS in 17 years following the planned retirement of current head, Cathy Lowenstein. -

Smus Sch Ties Summer 13.Pdf

SUMMER 2013 • ST. MICHAELS UNIVERSITY SCHOOL School On the Edge Fashion Online Teaching Technology In an ever-changing Both challenges and The benefits of new industry, four alumni share opportunities can be tools in the classroom how SMUS prepared them found in marketing and and the advent of a new for an unpredictable career. selling apparel online. artistic medium. Thanks to Our Sponsors and Golfers With your help, we raised $14,000 for the Alumni Endowment Fund 1 t the 2012 Annual SMUS Alumni & Friends Golf Invitational, A 112 golfers took to the Victoria Golf Club course in support of the Alumni Endowment Fund. The diverse group, comprised of men, women, parents, staff and alumni, enjoyed a seasonable and sunny afternoon oceanside. As incentives for great play – or great luck – there were opportunities to win big prizes with a hole-in-one, but none were taken home this year. Thanks to Steve Tate ’98 and all our organizers, volunteers and guests who continue to make this event a wonderful success. 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 1. Luke Mills, Colin Brown ’90, Francois Muller, Dave Fracy 2. Cathy Dixon, Kathy Jawl, Rani Singh, Joan Snowden 3. Steve Keeler, Vanessa (Young) Keeler ’84, Tracey Hagkull, Blair Hagkull 4. Dan Matthews, Blane Fowler, Michael Burrows, Jack Foster 5. Lisa Matthews, Allison Fowler 6. Mat Geddes ’93 7. Steve Selina ’81, Jim Brust, Ted Balderson ’82, Jim Taylor 8. Andy Maxwell ’79, Susanna Crofton ’80, Frank Corbett, Danielle Topliss ’91 9. Chuck Hemingway ’88, John Fraser, Travis Lee ’88 10. -

2020-2021 COURSE SELECTION GUIDE in the Coming Weeks

2020-2021 COURSE SELECTION GUIDE Dear Parents ~ Welcome to Shawnigan! In the coming weeks, incoming students for grades 8 through 12 will begin the course selection process for the 2020-2021 school year. The online version of the course selection form will be used by our office to support accuracy, parental involvement and communication among all those involved as we attempt to find the best courses for each individual student. The Academic Office can be contacted in a variety of ways, but for specific course selection questions and to submit your choices, please email [email protected]. To get full course descriptions of the BC curriculum that Shawnigan delivers, please see the curriculum documents on the curriculum.gov.bc.ca website. For descriptions of our AP courses, please visit the apstudent.collegeboard.org website. How the process will work: • Please use this document to inform your course selection. • Please send your choices to [email protected] within the next two weeks. • For all grades, the attached information should answer most questions. • For some grades, there are prescribed courses that all students take, while in others, there are many choices including Honours (denoted with a *) and AP level classes. • It is important that you and your child have the correct information when choosing classes. While changes to courses are possible at a later date, the timetable is staffed and built based on student requests. So we ask that course selection be completed with the intent of staying with the courses chosen. • You will notice that there is no Social Studies 11 course listed. -

Cowichan Region Sport Tourism Guide

Cowichan Region Sport Tourism Guide Ladysmith • Chemainus • Lake Cowichan • Duncan Cowichan Bay • Mill Bay • Shawnigan Lake Vancouver Island, British Columbia For 40 years, the BC Games have brought together British Columbians to this biennial celebration of sport and community. An important sport development opportunity, the BC Winter and BC Summer Games have been the starting point for many athletes who have gone on to international success, including Olympians and Paralympians Brent Hayden (swimming), Carol Huynh (wrestling,) and Richard Peter (wheelchair basketball). As the host for the 2018 BC Summer Games, 3,000 Cowichan area volunteers welcome thousands of athletes, coaches, officials, and spectators from July 19-22. Sport venues and facilities throughout the Cowichan region set the stage for 3,700 participants to compete in 19 sports. The BC Games leave a lasting legacy of economic impact, experienced volunteers, enhanced partnerships and community pride. 2018 marks the 40th anniversary of the BC Games, and Cowichan is a proud host of this milestone celebrating the spirit of competition, pride, inspiration, and excellence that have been the cornerstones of the BC Games since 1978. 2 www.cvrd.bc.ca/sportstourism Table of Contents 4 Why Choose Cowichan? 7 Sports Facilities 9 Multi-Sport Centres 19 Aquatics 14 Arenas 20 Golf 15 Fields 22 Gymnasiums/Indoor Sports 18 Curling Rinks 23 Adventure Sports and Activities 24 Meet our Communities 27 Attractions and Activities 28 Lodging and Eateries 29 Transportation 30 Resources and Contacts Front Cover: Cowichan Sportsplex Ball Fields www.cvrd.bc.ca/sportstourism 3 The Cowichan Region The Cowichan Region is located midway between Victoria and Nanaimo, about an hour’s drive to each, on beautiful Southern Vancouver Island.