Celebrating the Women's Building

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ART on the WALLS ARTISTS RIGHTS of INTEGRITY & ATTRIBUTION in MURALS & SCULPTURES Brooke Oliver, Attorney Brooke Oliver Law Group, P.C

ART ON THE WALLS ARTISTS RIGHTS OF INTEGRITY & ATTRIBUTION IN MURALS & SCULPTURES Brooke Oliver, Attorney Brooke Oliver Law Group, P.C. 50 Balmy Alley San Francisco, CA 94110 415/641-1116 www.artemama.com BIO: BROOKE OLIVER represents artists, activists, and entrepreneurs. She founded Brooke Oliver Law Group, P.C., an art, entertainment and business law firm. She has been called a “folk hero of copyright law” for her work in protecting muralists and activists’ intellectual property and murals. Her business practice helps creative entrepreneurs establish and grow companies and protect their intellectual property. The firm’s litigation practice emphasizes copyright and trademark. Clients include the Jerry Garcia Estate LLC, artists Michael Parkes, Eyvind Earle, Judy Baca, and Juana Alicia, and photographers on behalf of Corbis. She is intellectual property counsel for Dolores Huerta, the Cesar E. Chavez Foundation, the United Farm Workers Union/A.F.L.-C.I.O, the Mexican Museum, Swell Cinema, and many graphic designers, photographers, and filmmakers. She is general counsel for San Francisco Pride Celebration, and the San Francisco World Music Festival. Business clients include Rocket Science, Chi Living, Toys in Babeland, Fattoush and La Posta restaurants, EcoRep, Pyramind, Mayacama Golf Club, Varnish Fine Art Gallery, and Herter Studio. CAUTIONARY NOTE: This article is for research and reference purposes only. It does not constitute and should not be considered to be legal advice. Every effort has been made to assure its accuracy as of the date it was written, but the law constantly evolves and changes. Artists and others with a specific legal question or problem should retain a knowledgeable attorney to advise them. -

ON AIR, ONLINE, on the GO JANUARY 2018 | MEMBER GUIDE ADVERTISEMENTS from the President Where to Tune In

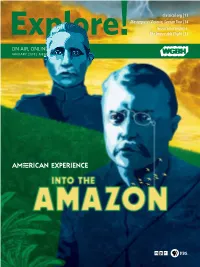

Classical.org | 13 Masterpiece/Victoria, Season Two | 14 Nova/Solar Impulse: The Impossible Flight | 21 ON AIR, ONLINE, ON THE GO JANUARY 2018 | MEMBER GUIDE ADVERTISEMENTS From the President Where to Tune in In with the New! TV We begin the new year in a spirit of exploration and adventure as we head into a new season of programming at WGBH. This month, WGBH brings you a host of inspiring, Digital broadcast FiOS RCN Cox Charter (Canada) Bell ExpressVu entertaining and educational premieres from Masterpiece, American Comcast Experience, Nova, Antiques Roadshow and more! WGBH 2 2.1 2 2 2 2 2 284 American Experience’s Into the Amazon (pg. 12) tells the remarkable WGBH 2 HD 2.1 802 502 602 1002 782 819 story of the 1914 journey taken by President Theodore Roosevelt (left) and WGBX 44 44.1 16 44 14 804 21 n/a Brazilian explorer Candido Rondon into the heart of the South American rainforest. With a crew of more than WGBX 44 HD 44.1 801 544 n/a n/a n/a n/a 140 Brazilians, Roosevelt and Rondon World 2.2 956 473 94 807 181 n/a set out to explore an uncharted Create 44.3 959 474 95 805 182 n/a Amazon tributary, along the way WGBH Kids 44.4 958 472 93 n/a 180 n/a battling the unforgiving landscape, Boston Kids & n/a 22 n/a 3 n/a n/a n/a disease and countless other dangers. Family (Boston only) “Like all great journeys, the story Channel numbers and availability may vary by community. -

Wilkinson College of Arts, Humanities, & Social Sciences

2019–2020 WILKINSON COLLEGE OF ARTS, HUMANITIES, & SOCIAL SCIENCES Annual Report Table of Contents Greetings ............................................................................................................................ 2-3 2019–2020 Highlights .......................................................................................................... 4-5 Wilkinson College Travel Courses ........................................................................................... 6-7 La Frontera/The Border Series ................................................................................................ 8-9 Engaging the World: Significance of Race Film Series ............................................................ 10 -11 Wilkinson College Sponsored Projects ................................................................................. 12-13 Wilkinson College Career Advisor ....................................................................................... 14-15 Wilkinson College Presidential Fellows ................................................................................. 16 -17 Wilkinson College Departments ............... .............................................................................18-37 Art .......................................................................................................................20-21 English ..................................................................................................................22-23 History ................................................................................................................ -

Black LGBTQ People

GLBT Historical Society Dr. John P. De Cecco Archives and Special Collections Holdings Related to Black LGBTQ People Last edited: March 2020 Prepared by: Marjorie Bryer This research guide is intended to help users locate holdings related to Black people and collections that document the Black experience at the GLBT Historical Society. It highlights holdings in the following areas: ● Organizational records and personal papers ● Periodicals ● Oral Histories While this guide was carefully curated, it should not be taken as comprehensive. Other collections may contain materials and/or discuss issues related to the Black experience or, more broadly, race and racial justice. Please note that many large collections of photographs, papers, and audiovisual materials will contain relevant materials – even if their focus is not specifically on Black people. Researchers are encouraged to conduct their own searches of the catalog and finding aids. Please contact the GLBT Historical Society Archives ([email protected]) with any questions or comments and for more information on how to access digitized audiovisual holdings – which are not covered extensively here. Organizational records and personal papers (listed alphabetically): Bay Area Women of Color BDSM Photo Project collection (#2004-07) dates: 2004 – 2019, size: 0.4 linear feet This collection contains materials that document the photo exhibition and panel discussion held at the San Francisco Citadel in 2004, entitled “Bay Area Women of Color BDSM Photo Project.” The Project later changed its name to the Bay Area Women of Color Photo Project, and there are news clippings about later exhibits. The mission was to expand the aesthetic and cultural perception promoting artistically tasteful photographic images of Women of Color in the fine arts and elegant lifestyles. -

Reevaluating Community Murals and Existing Practices

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Theses (Historic Preservation) Graduate Program in Historic Preservation 2016 Balancing Past and Present: Reevaluating Community Murals and Existing Practices Sang Weon Bae Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/hp_theses Bae, Sang Weon, "Balancing Past and Present: Reevaluating Community Murals and Existing Practices" (2016). Theses (Historic Preservation). 600. https://repository.upenn.edu/hp_theses/600 Suggested Citation: Bae, Sang (2016). Balancing Past and Present: Reevaluating Community Murals and Existing Practices. (Masters Thesis). University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA. This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/hp_theses/600 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Balancing Past and Present: Reevaluating Community Murals and Existing Practices Abstract In the late 1960s, mural painting was adopted as a channel of social expression for those who felt that they did not possess the agency to establish their own cultural representation and identity. These people, usually from ethnic enclaves and disenfranchised urban areas, painted on walls combining imageries adopted from their cultural roots with contemporary styles and inspiration to visually communicate their concerns, hopes, and culture as a collective community. This practice of community muralism has continued in various areas to present. However, these community murals are quickly and consistently disappearing from the built environment today, despite the conservation efforts by various organizations and professionals. Within this context, this study reevaluates the murals as a cultural resource and the existing practices in which they are addressed to reveal the challenges at the root of the problem. Introducing the often neglected concept of ephemerality to the discussion of these murals, this study determines that the resource is more complicated than is regarded by the preservation field. -

02/01/21 Special Meeting

MEASURE O BOND OVERSIGHT COMMITTEE AGENDA Measure O Bond Oversight Committee Special Meeting Acting Secretary Jenny Wyant Monday, February 1, 2021 [email protected] 6:00 pm PUBLIC ADVISORY: THIS MEETING WILL BE CONDUCTED EXCLUSIVELY THROUGH VIDEOCONFERENCE AND TELECONFERENCE Pursuant to Section 3 of Executive Order N-29-20, issued by Governor Newsom on March 17, 2020, this meeting of the Measure O Bond Oversight Committee will be conducted exclusively through teleconference and Zoom videoconference. Please be advised that pursuant to the Executive Order, and to ensure the health and safety of the public by limiting human contact that could spread the COVID-19 virus, there will not be a physical meeting location available. To access the meeting remotely using the internet: Join from a PC, Mac, iPad, iPhone, or Android device: Use URL - https://zoom.us/j/93950296629 . If you do not wish for your name to appear on the screen, then use the drop down menu and click on "rename" to rename yourself to be anonymous. To request to speak, use the “raise hand” icon on the screen. To join by phone: Dial +1 669 900 6833 and Enter Meeting ID: 939 5029 6629. If you wish to comment during the public comment portion of the agenda, press *9 and wait to be recognized by the Chair. Written communications submitted by mail or e-mail to the Measure O Bond Oversight Committee by 5:00 p.m. the business day before the Committee meeting will be distributed to the members of the Committee in advance of the meeting and retained as part of the official record. -

2020 Candidate Statements

Candidate for MAYOR I, JESSE ARREGUIN, hereby declare that I am a candidate for an elective office in the City of Berkeley, and make the following statement: 1. That my name is Jesse Arreguín 2. The office for which I am a candidate is Mayor 3. That my residence is 1528 Henry Street, Berkeley, CA 94709 4. The place of my birth is Fresno, CA 5. My present occupation is Mayor, City of Berkeley 6. I have held the following public offices: Mayor, City of Berkeley; President, Association of Bay Area Governments (ABAG); Chair, ABAG Housing Methodology Committee; Joint ABAG-MTC Governance Committee; Bay Area Regional Collaborative; Alternate Commissioner, San Francisco Bay Conservation and Development Commission; Commissioner, Alameda County Transportation Commission; East Bay Community Energy Board of Directors, Alameda County Waste Management Authority; East Bay Regional Sports Fields JPA; 2x2 Committee of the City Council and Board of Education; 4x4 Committee on Housing, City Council/Rent Stabilization Board; 3x3 Committee of the Berkeley City Council and Berkeley Housing Authority; Councilmember, City of Berkeley, District 4; Commissioner, Rent Stabilization Board; Zoning Adjustments Board; Planning Commission; Housing Advisory Commission; Downtown Area Plan Advisory Committee. 7. Record of community service: Bernie Sanders Delegate to the DNC; Berkeley Tenants Union, Berkeley Progressive Alliance, Sierra Club Northern Alameda County Group. 8. I am a taxpayer in the City of Berkeley. 9. In 2016 you entrusted me to be Mayor of this exceptional city. It's an honor to lead a community that always stands for democracy, equity, and justice. Nobody could have imagined the challenges we've faced. -

A NEW COLOR: the ART of BEING EDYTHE BOONE to Premiere on AMERICA REFRAMED a Film by Marlene “Mo” Morris

A NEW COLOR: THE ART OF BEING EDYTHE BOONE To Premiere on AMERICA REFRAMED A film by Marlene “Mo” Morris Tuesday, February 14, 2017 at 8 p.m. on WORLD Channel “Art and activism often go hand in hand, yet, even among artists whose work is oriented toward social justice, it’s rare to find someone whose creativity and community-building work are as naturally entwined as Berkeley’s Edythe Boone.” – Jessica Zack, San Francisco Chronicle January 7, 2017 – (New York, NY) – Marlene “Mo” Morris’ debut documentary feature A NEW COLOR: THE ART OF BEING EDYTHE BOONE will have its U.S. MEDIA RELATIONS television premiere Tuesday, February 14, 2017 at 8 p.m. on WORLD Channel Neyda Martinez 917 656 7846 (check local listings), as part of the new season of public media’s AMERICA [email protected] REFRAMED. The documentary series is dedicated to highlighting intimate stories by AMERICA emerging and veteran filmmakers who are chronicling an ever-changing America. REFRAMED The broadcast will be followed by free streaming for audiences across the U.S. at 20 Jay Street Suite 940 www.worldchannel.org/americareframed starting on February 15th. Brooklyn, NY 11201 P: 212-989-8121 A New Color focuses on the life and work of muralist, activist and educator, Edythe F: 212-989-8230 americareframed.com (Edy) Boone, a self-taught artist from East Harlem who moved to the San Francisco Bay Area in search of a safe environment for her children. Filmed over five years, Morris follows Boone, the spirited and captivating septuagenarian who became an artist/activist simply because empowering and building community is “the right thing to do.” Concerned about the exceedingly high number of senseless deaths amongst young Black men in the U.S., Boone uses these injustices as part of the narrative in her murals. -

AGENDA SPECIAL MEETING of the PLANNING COMMISSION Click Here to View the Entire Agenda Packet

Planning Commission AGENDA SPECIAL MEETING OF THE PLANNING COMMISSION Click here to view the entire Agenda Packet Wednesday, September 30, 2020 7:00 PM PUBLIC ADVISORY: THIS MEETING WILL BE CONDUCTED EXCLUSIVELY THROUGH VIDEOCONFERENCE AND TELECONFERENCE Pursuant to Section 3 of Executive Order N- 29-20, issued by Governor Newsom on March 17, 2020, this meeting of the Planning Commission (PC) will be conducted exclusively through teleconference and Zoom videoconference. Please be advised that pursuant to the Executive Order and the Shelter-in-Place Order, and to ensure the health and safety of the public by limiting human contact that could spread the COVID19 virus, there will not be a physical meeting location available. To access the meeting remotely: Join from a PC, Mac, iPad, iPhone, or Android device: Please use this URL https://zoom.us/j/97055841131. If you do not wish for your name to appear on the screen, then use the drop down menu and click on "rename" to rename yourself to be anonymous. To request to speak, use the “raise hand” icon by rolling over the bottom of the screen. To join by phone: Dial 1 669 900 6833 and enter Meeting ID: 970 5584 1131. If you wish to comment during the public comment portion of the agenda, Press *9 and wait to be recognized by the Chair. Please be mindful that the video conference and teleconference will be recorded. All rules of procedure and decorum that apply for in-person Planning Commission meetings apply for Planning Commission meetings conducted by teleconference or videoconference. See “MEETING PROCEDURES” below. -

LGBTQ America: a Theme Study of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, and Queer History Is a Publication of the National Park Foundation and the National Park Service

Published online 2016 www.nps.gov/subjects/tellingallamericansstories/lgbtqthemestudy.htm LGBTQ America: A Theme Study of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, and Queer History is a publication of the National Park Foundation and the National Park Service. We are very grateful for the generous support of the Gill Foundation, which has made this publication possible. The views and conclusions contained in the essays are those of the authors and should not be interpreted as representing the opinions or policies of the U.S. Government. Mention of trade names or commercial products does not constitute their endorsement by the U.S. Government. © 2016 National Park Foundation Washington, DC All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reprinted or reproduced without permission from the publishers. Links (URLs) to websites referenced in this document were accurate at the time of publication. PLACES Unlike the Themes section of the theme study, this Places section looks at LGBTQ history and heritage at specific locations across the United States. While a broad LGBTQ American history is presented in the Introduction section, these chapters document the regional, and often quite different, histories across the country. In addition to New York City and San Francisco, often considered the epicenters of LGBTQ experience, the queer histories of Chicago, Miami, and Reno are also presented. SAN FRANCISCO:25 PLACING LGBTQ HISTORIES IN THE CITY BY THE BAY Donna J. Graves and Shayne E. Watson Introduction San Francisco is internationally recognized as a magnet and place of pilgrimage for LGBTQ people and a critical proving ground for advancements in queer culture, politics, and civil rights. -

Je Suis… I Am… Motivated to Create VSA International Art Program for CHILDREN with DISABILITIES a Jean Kennedy Smith Arts and Disability Program

Yo soy… Je suis… I am… Motivated to Create VSA International Art Program FOR CHILDREN WITH DISABILITIES A Jean Kennedy Smith Arts and Disability Program Teacher Resource Guide EDITION 2017-18 A series of visual art lesson plans designed to engage students with disabilities. Yo Soy… Je Suis… I am… Motivated to Create VSA International Art Program for Children with Disabilities A Jean Kennedy Smith Arts and Disability Program Teacher Resource Guide Edition 2017-2018 Office of VSA and Accessibility Betty Siegel, Director, VSA and Accessibility Stephanie Litvak, Manager, VSA Affiliates Jessica Swanson, Manager, Accessibility Jenna Gabriel, Manager, Special Education The John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts 2700 F Street, NW Washington, DC 20566 (202) 416-8898 [email protected] http://education.kennedy-center.org/education/vsa/programs/vsa_iap.cfm Lesson plans by: Shannon Hayes, M.Ed. Jenna Gabriel, Ed.M., Editor Funding for the VSA International Art Program for Children with Disabilities is provided by the U.S. Department of Education. Kennedy Center education and related artistic programming is made possible through the generosity of the National Committee for the Performing Arts and the President’s Advisory Committee on the Arts. International Programming at the Kennedy Center is made possible through the generosity of the Kennedy Center International Committee on the Arts. The contents of this publication may have been developed under a grant from the U.S. Department of Education, but do not necessarily represent the policy of the U.S. Department of Education. You should not assume endorsement by the federal government. UBUNTU Yo soy… Je suis… I am… Motivated to Create Table of Contents INTRODUCTION . -

Juana Alicia: a Case Study of the Artist As Critical Muralist Allison Ann Connor San Jose State University

San Jose State University SJSU ScholarWorks Master's Theses Master's Theses and Graduate Research Spring 2016 Juana Alicia: a Case Study of the Artist as Critical Muralist Allison Ann Connor San Jose State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.sjsu.edu/etd_theses Recommended Citation Connor, Allison Ann, "Juana Alicia: a Case Study of the Artist as Critical Muralist" (2016). Master's Theses. 4684. DOI: https://doi.org/10.31979/etd.u3wr-h2z2 https://scholarworks.sjsu.edu/etd_theses/4684 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Master's Theses and Graduate Research at SJSU ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of SJSU ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. JUANA ALICIA: A CASE STUDY OF THE ARTIST AS CRITICAL MURALIST A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Department of Art History and Visual Culture San José State University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts by Allison Connor May 2016 © 2016 Allison Connor ALL RIGHTS RESERVED The Designated Thesis Committee Approves the Thesis Titled JUANA ALICIA: A CASE STUDY OF THE ARTIST AS ACTIVIST by Allison Connor APPROVED FOR THE DEPARTMENT OF ART AND ART HISTORY SAN JOSÉ STATE UNIVERSITY March 2016 Dr. Anne Simonson Department of Art History and Visual Culture Professor Patricia Albers Department of Art History and Visual Culture Dr. Johanna Movassat Department of Art History and Visual Culture ABSTRACT JUANA ALICIA: A CASE STUDY OF THE ARTIST AS CRITICAL MURALIST Much has been written on Mexican Muralism and on the resurgence of mural art in the United States, and Chicana/o murals in San Francisco in particular, but very little has been written about mural artist Juana Alicia specifically, and none of this material has been gathered into one document.