The Construction of Dependency: the Case of the Grand Rapids Hydro Project

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chapter 4 – Project Setting

Chapter 4 – Project Setting MINAGO PROJECT i Environmental Impact Statement TABLE OF CONTENTS 4. PROJECT SETTING 4-1 4.1 Project Location 4-1 4.2 Physical Environment 4-2 4.3 Ecological Characterization 4-3 4.4 Social and Cultural Environment 4-5 LIST OF FIGURES Figure 4.1-1 Property Location Map ......................................................................................................... 4-1 Figure 4.4-1 Communities of Interest Surveyed ....................................................................................... 4-6 MINAGO PROJECT ii Environmental Impact Statement VICTORY NICKEL INC. 4. PROJECT SETTING 4.1 Project Location The Minago Nickel Property (Property) is located 485 km north-northwest of Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada and 225 km south of Thompson, Manitoba on NTS map sheet 63J/3. The property is approximately 100 km north of Grand Rapids off Provincial Highway 6 in Manitoba. Provincial Highway 6 is a paved two-lane highway that serves as a major transportation route to northern Manitoba. The site location is shown in Figure 4.1-1. Source: Wardrop, 2006 Figure 4.1-1 Property Location Map MINAGO PROJECT 4-1 Environmental Impact Statement VICTORY NICKEL INC. 4.2 Physical Environment The Minago Project is located within the Nelson River sub-basin, which drains northeast into the southern end of the Hudson Bay. The Minago River and Hargrave River catchments, surrounding the Minago Project Site to the north, occur within the Nelson River sub-basin. The William River and Oakley Creek catchments at or surrounding the Minago Project Site to the south, occur within the Lake Winnipeg sub-basin, which flows northward into the Nelson River sub-basin. The topography in these watersheds varies between elevation 210 and 300 m.a.s.l. -

Origin of the Name Manitoba

On May 2, 1870, Sir John A. Macdonald The Origin of the Name The Narrows of Lake Manitoba (on PTH 68, 60 km west of the junction of announced that a new province was to enter Manitoba PTHs 6 and 68) Confederation under The Manitoba Act. He said the province’s name had been chosen for its pleasant sound and its associations with the The name Manitoba originated in the languages original inhabitants of the area. of the Aboriginal people who lived on the Prairies and travelled the waters of Lake Both the Cree and Assiniboin terms, and the Manitoba. legends and events associated with their use, are preserved forever in the name Manitoba. A These people, the Cree and Assiniboin First plaque commemorating its origin is located on Nations, introduced European explorers, traders the east side of the Lake Manitoba Narrows. and settlers to the region and its waterways. They also passed on to the newcomers the ancient names and poetic legends associated with the places they inhabited. More than two centuries of contact and trade between the Europeans and First Nations produced a blending of their languages. From Aboriginal name and legend to official title of the province, the evolution of the name Manitoba mirrors the history of the region. At the Lake Manitoba Narrows a strong wind can send waves washing against the limestone During the Red River Resistance of 1869-70, rocks of an offshore island. The unique sound Spence joined Louis Riel’s Métis Council. In from the waves is said to be the Manitou, or the spring of 1870, delegates from this council Great Spirit (in Ojibway, “Manito-bau”). -

New the Pas Bridge Key to North Roads

Manitoba Government NEWS Public Information Branch Legislative Bldg., Winnipeg SERVICE MANITOBA Phone 946-7439 Date: October 25, 1968. NEW THh PAS BKIMit KEY TO NORTH ROADS Number 10 highway in northern Manitoba is undergoing a major facelifting. Included are a new bridge at The Pas, re-location of the roadway in the vicinity of Flin Flon, and paving and improvement programs in the vicinity of The Pas. Latest step in this development was the ceremony held Saturda71 October 19, to mark the start of work on the bridge over the Saskatchewan River at The Pas. Transportation Minister Stewart E. McLean referred to the bridge as a "new and vital link" in the northern road system of the province. Participating in the ceremony were Minister of Consumer and Corporate Affairs John B. Carroll, Minister of Labour C.H. Witney, Mayor Harry Trager of The Pas, and Chief Gordon Lathlin of The Pas Indian band. The $1.63 million bridge is to be made of steel and re-inforced concrete and will be about 1,200 feet long. The new bridge is to be finished in the late fall of 1969, and will improve truck service into the north, which is now handicapped by load restrictions on the present obsolete bridge. Tenders have been opened for the grading of the last portion of the re-location of No. 10 highway at Flin Flon. Low bid of the six submitted is $259,746 from Pneumatic Drilling and Blasting Limited of St. James. This covers 1.5 miles and includes blasting and removal of 47,000 cubic yards of rock, with work to be completed by next summer. -

Grand Rapids GS Short Term Extension Licence Request (2014

360 Portage Ave (16) Winnipeg Manitoba Canada R3C 0G8 Telephone / No de téléphone : 204-360-3018 Fax / No de télécopieur : 204-360-6136 [email protected] 2014 10 30 Mr. Rob Matthews Manager, Water Use Licensing Manitoba Conservation and Water Stewardship Box 16 - 200 Saulteaux Crescent Winnipeg MANITOBA R3J 3W3 Dear Mr. Matthews: GRAND RAPIDS WATER POWER SHORT-TERM EXTENSION LICENCE REQUEST We request a five year short-term extension licence for the Grand Rapids Generating Station under the provisions of Section 92(1) of Water Power Regulation 25/88R. We have included a Short Term Extension Report as supporting documentation and will continue to work with your Section to address this Water Power licence. Manitoba Hydro continues to operate the Grand Rapids Generating Station in accordance with the Final Licence issued on May 30, 1975 under the Water Power Act. The Final Licence expires on January 2, 2015. Manitoba Hydro requested a renewal licence on December 17, 2010. However, due to licensing requirements for other projects, Manitoba Hydro is requesting a short-term extension licence to allow the licence renewal to occur at a later date. Please call me at 204-360-3018 if you need additional information. Yours truly, pp: Brian Giesbrecht W.V. Penner, P. Eng. Manager Hydraulic Operations Department Encl. MJD/sl/ 00112-07311-0014_00 WATER POWER ACT LICENCES GRAND RAPIDS GENERATING STATION SHORT TERM LICENCE EXTENSION APPLICATION SUPPORTING DOCUMENTATION Prepared for: Manitoba Water Stewardship 200 Saulteaux Crescent Winnipeg MB R3J 3W3 Prepared by: Manitoba Hydro 360 Portage Avenue Winnipeg MB R3C 0G8 October 29, 2014 Report No: PS&O – 14/08 HYDRAULIC OPERATIONS DEPARTMENT POWER SALES & OPERATIONS DIVISION GENERATION OPERATIONS WATER POWER ACT LICENCES GRAND RAPIDS SHORT TERM LICENCE EXTENSION APPLICATION SUPPORTING DOCUMENTATION Originally signed by P.Chanel Originally signed by PREPARED BY: P.Chanel P. -

TRAPPERS' FESTIVAL OFFERS the Pas, Manitoba

Bureau of Travel and Publicity partirtent of Industry and CoMmerce. WinniPeg, Manitoba Release Date: Dote of Issue: -TRAPPERS' FESTIVAL OFFERS Immediately -RICH SLICE OF NORTHERN LIFE January 12, 1954. The Pas, Manitoba:- All the color and adventure of Canada's northland will be wrapped into a four-day package of fun and furor for the Seventh Annual Northern Manitoba Trappers' Festival at The Pas February 2 to 5. Traders, trappers, eskimos and Indian Chiefs will flock to the festival to take part in the 200-mile dog derby, the goose-calling, bannock-baking and scores of other "frontier" contests. The Pas, a small town of big contrasts, is perched on the fringe of North America's last pioneer area and provides a suitably rough-hewn background for the snow-show which annually attracts visitors from far and near. The local citizenry, 4,000 brisk fn busy people are always parka-ed and mukluked and beaded-for-bear during the festival week and riotous fever of gaiety rocks the tom from the Indian reservation on the outskirts to the sedate and proper homes in the best residential areas. This is a "souped-up" offering of the northerners' famous spirit and friendliness that never fails to impress visiting spectators who are wide-eyed and eager to make use of the "dog-team taxis", wear the uninhibited headgear made of foxtails, dine on beaver-tail soup, buffalo steaks, caribou tongues, porcupine roasts and join in the dancing in the streets. - more - For further information) and photographs write to the Bureau of Travel and Room 25-4 Legislative Buildings, Winnipeg Manitoba - 2 - From the official start of the 200-mile Championship dog derby which gets the festival underway to the gala Fur Queen's Ball and the last hectic session at the Mad Trappers' Rendezvous there is something happening all the time ice- fishing contests, snow-shoe marathons dog-handling displays, Indian jigging, stage- shows, trap-setting, rat-skinning, fish-eating, fireworks and dancing for young and old. -

Physician Directory

Physician Directory, Currently Practicing in the Province Information is accurate as of: 9/24/2021 8:00:12 AM Page 1 of 97 Name Office Address City Prov Postal Code CCFP Specialty Abara, Chukwuma Solomon Thompson Clinic, 50 Selkirk Avenue Thompson MB R8N 0M7 CCFP Abazid, Nizar Rizk Health Sciences Centre, Section of Neonatology, 665 William Avenue Winnipeg MB R3E 0L8 Abbott, Burton Bjorn Seven Oaks General Hospital, 2300 McPhillips Street Winnipeg MB R2V 3M3 CCFP Abbu, Ganesan Palani C.W. Wiebe Medical Centre, 385 Main Street Winkler MB R6W 1J2 CCFP Abbu, Kavithan Ganesan C.W. Wiebe Medical Centre, 385 Main Street Winkler MB R6W 1J2 CCFP Abdallateef, Yossra Virden Health Centre, 480 King Street, Box 400 Virden MB R0M 2C0 Abdelgadir, Ibrahim Mohamed Ali Manitoba Clinic, 790 Sherbrook Street Winnipeg MB R3A 1M3 Internal Medicine, Gastroenterology Abdelmalek, Abeer Kamal Ghobrial The Pas Clinic, Box 240 The Pas MB R9A 1K4 Abdulrahman, Suleiman Yinka St. Boniface Hospital, Room M5038, 409 Tache Avenue Winnipeg MB R2H 2A6 Psychiatry Abdulrehman, Abdulhamid Suleman 200 Ste. Anne's Road Winnipeg MB R2M 3A1 Abej, Esmail Ahmad Abdullah Winnipeg Clinic, 425 St. Mary Ave Winnipeg MB R3C 0N2 CCFP Gastroenterology, Internal Medicine Abell, Margaret Elaine 134 First Street, Box 70 Wawanesa MB R0K 2G0 Abell, William Robert Rosser Avenue Medical Clinic, 841 Rosser Avenue Brandon MB R7A 0L1 Abidullah, Mohammad Westman Regional Laboratory, Rm 146 L, 150 McTavish Avenue Brandon MB R7A 7H8 Anatomical Pathology Abisheva, Gulniyaz Nurlanbekovna Pine Falls Health Complex, 37 Maple Street, Box 1500 Pine Falls MB R0E 1M0 CCFP Abo Alhayjaa, Sahar C W Wiebe Medical Centre, 385 Main Street Winkler MB R6W 1J2 Obstetrics & Gynecology Abou-Khamis, Rami Ahmad Northern Regional Health, 867 Thompson Drive South Thompson MB R8N 1Z4 Internal Medicine Aboulhoda, Alaa Samir The Pas Clinic, Box 240 The Pas MB R9A 1K4 General Surgery Abrams, Elissa Michele Meadowwood Medical Centre, 1555 St. -

The Arctic Gateway Group Is Owned by First Nations and Bayline Communities, Fairfax and Agt Foods, Building a Natural Resources

THE ARCTIC GATEWAY GROUP IS OWNED BY FIRST NATIONS AND BAYLINE COMMUNITIES, FAIRFAX AND AGT FOODS, BUILDING A NATURAL RESOURCES GATEWAY THROUGH THE ARCTIC TO THE WORLD. Arctic Gateway Group LP Arctic_Gateway ArcticGateway 728 Bignell Ave. ArcticGateway The Pas, MB R9A 1L8 1-888-445-1112 [email protected] www.arcticgateway.com ABOUT THE GATEWAY The Arctic Gateway Group LP owns and operates the Port of Churchill, Canada’s only Arctic seaport serviced by rail, on the Hudson Bay Railway, running from The Pas to Churchill, Manitoba. Strategically located on the west coast of Hudson Bay, the Arctic Gateway is the front door to Western Canada, linking Canadian trade in resources to the global marketplace. The Arctic Gateway’s logistical advantage, rail assets and unique location provide direct and efficient routes to markets for Canada’s abundant natural resources and manufactured products, while connecting Canadian consumers and importers to the world marketplace via the North. Hudson Bay Railway (CN, KRC) port of The Hudson Bay Railway is made up of 627 miles port location interchange churchill hudson bay railroad (hbr) agg HBR operating of former Canadian National (CN) trackage, with a agg railroad agreement network that connects with CN in The Pas, running north through Manitoba to the Hudson Bay at the lynn lake kelsey gillam Port of Churchill. The Hudson Bay Railway is a vital transportation pukatawagan thompson link in northern Manitoba, hauling perishables, automobiles, frac ilford sherridon thicket Flin Flon sand, construction material, heavy and dimensional equipment, sherritt jct wabowden scrap, hazardous materials, kraft paper, concentrates, containers, Cranberry portage the pas the pas jct fertilizer, wheat and other grain products. -

Wallace Mining and Mineral Prospects in Northern

r Geology V f .ibrary TN 27 7A3V/1 WALLACE MINING AND MINERAL PROSPECTS IN NORTHERN MANITOBA THE LIBRARY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA LOS ANGELES University of British Columbia D. REED LIBRARY The RALPH o DEPARTMENT OF GEOLOGY UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA LOS ,-XGELES, CALIF. Northern Manitoba Bulletins Mining and Mineral Prospects in Northern Manitoba BY R. C. WALLACE PUBLISHED BY AUTHORITY OF GOVERNMENT OP MANITOBA OFFICE OF COMMISSIONER OF NORTHERN MANITOBA The Pas, Manitoba Northern Manitoba Bulletins Mining and Mineral Prospects in Northern Manitoba BY R. C. WALLACE PUBLISHED BY AUTHORITY OF GOVERNMENT OF MANITOBA OFFICE OF COMMISSIONER OF NORTHERN MANITOBA The Pas, Manitoba CONTENTS Chapter Page I. Introductory 5 II. Geological features ... 7 III. History of Mining Development 12 IV. Metallic Deposits: (A) Mineral belt north of The Pas .... 20 (1) Flin Flon and Schist Lake Districts. .... ....20 (2) Athapapuskow Lake District ..... ....27 (3) Copper and Brunne Lake Districts .....30 (4) Herb and Little Herb Lake Districts .... .....31 (5) Pipe Lake, Wintering Lake and Hudson Bay Railway District... 37 (B) Other mineral areas .... .....37 V. Non-metallic Deposits 38 (a) Structural materials 38 (ft) Fuels 38 (c) Other deposits. 39 VI. The Economic Situatior 40 VII. Bibliography 42 Appendix: Synopsis of Regulations governing the granting of mineral rights.. ..44 NORTHERN MANITOBA NORTHERN MANITOBA Geology Library INTRODUCTORY CHAPTER I. INTRODUCTORY Scope of Bulletin The purpose of this bulletin is to give a short description of the mineral deposits, in so far as they have been discovered and developed, in the territory which was added to the Province of Manitoba in the year 1912. -

Geomorphic and Sedimentological History of the Central Lake Agassiz Basin

Electronic Capture, 2008 The PDF file from which this document was printed was generated by scanning an original copy of the publication. Because the capture method used was 'Searchable Image (Exact)', it was not possible to proofread the resulting file to remove errors resulting from the capture process. Users should therefore verify critical information in an original copy of the publication. Recommended citation: J.T. Teller, L.H. Thorleifson, G. Matile and W.C. Brisbin, 1996. Sedimentology, Geomorphology and History of the Central Lake Agassiz Basin Field Trip Guidebook B2; Geological Association of CanadalMineralogical Association of Canada Annual Meeting, Winnipeg, Manitoba, May 27-29, 1996. © 1996: This book, orportions ofit, may not be reproduced in any form without written permission ofthe Geological Association ofCanada, Winnipeg Section. Additional copies can be purchased from the Geological Association of Canada, Winnipeg Section. Details are given on the back cover. SEDIMENTOLOGY, GEOMORPHOLOGY, AND HISTORY OF THE CENTRAL LAKE AGASSIZ BASIN TABLE OF CONTENTS The Winnipeg Area 1 General Introduction to Lake Agassiz 4 DAY 1: Winnipeg to Delta Marsh Field Station 6 STOP 1: Delta Marsh Field Station. ...................... .. 10 DAY2: Delta Marsh Field Station to Brandon to Bruxelles, Return En Route to Next Stop 14 STOP 2: Campbell Beach Ridge at Arden 14 En Route to Next Stop 18 STOP 3: Distal Sediments of Assiniboine Fan-Delta 18 En Route to Next Stop 19 STOP 4: Flood Gravels at Head of Assiniboine Fan-Delta 24 En Route to Next Stop 24 STOP 5: Stott Buffalo Jump and Assiniboine Spillway - LUNCH 28 En Route to Next Stop 28 STOP 6: Spruce Woods 29 En Route to Next Stop 31 STOP 7: Bruxelles Glaciotectonic Cut 34 STOP 8: Pembina Spillway View 34 DAY 3: Delta Marsh Field Station to Latimer Gully to Winnipeg En Route to Next Stop 36 STOP 9: Distal Fan Sediment , 36 STOP 10: Valley Fill Sediments (Latimer Gully) 36 STOP 11: Deep Basin Landforms of Lake Agassiz 42 References Cited 49 Appendix "Review of Lake Agassiz history" (L.H. -

Lake Manitoba and Lake St. Martin Outlet Channels

Project Description Lake Manitoba and Lake St. Martin Outlet Channels Prepared for: Canadian Environmental Assessment Agency Submitted by: Manitoba Infrastructure January 2018 Project Description – January 2018 Table of Contents 1 GENERAL INFORMATION AND CONTACTS ................................................... 1 1.1 Nature of the Project and Proposed Location ..................................................... 1 1.2 Proponent Information ........................................................................................ 3 1.2.1 Name of the Project ......................................................................................... 3 1.2.2 Name of the Proponent ................................................................................... 3 1.2.3 Address of the Proponent ................................................................................ 3 1.2.4 Chief Executive Officer .................................................................................... 3 1.2.5 Principal Contact Person ................................................................................. 3 1.3 Jurisdictions and Other Parties Consulted .......................................................... 6 1.4 Environmental Assessment Requirements ......................................................... 7 1.4.1 Canadian Environmental Assessment Act, 2012 (Canada) ............................ 7 1.4.2 The Environment Act (Manitoba) ..................................................................... 8 1.5 Other Regulatory Requirements ........................................................................ -

Large Area Planning in the Nelson-Churchill River Basin (NCRB): Laying a Foundation in Northern Manitoba

Large Area Planning in the Nelson-Churchill River Basin (NCRB): Laying a foundation in northern Manitoba Karla Zubrycki Dimple Roy Hisham Osman Kimberly Lewtas Geoffrey Gunn Richard Grosshans © 2014 The International Institute for Sustainable Development © 2016 International Institute for Sustainable Development | IISD.org November 2016 Large Area Planning in the Nelson-Churchill River Basin (NCRB): Laying a foundation in northern Manitoba © 2016 International Institute for Sustainable Development Published by the International Institute for Sustainable Development International Institute for Sustainable Development The International Institute for Sustainable Development (IISD) is one Head Office of the world’s leading centres of research and innovation. The Institute provides practical solutions to the growing challenges and opportunities of 111 Lombard Avenue, Suite 325 integrating environmental and social priorities with economic development. Winnipeg, Manitoba We report on international negotiations and share knowledge gained Canada R3B 0T4 through collaborative projects, resulting in more rigorous research, stronger global networks, and better engagement among researchers, citizens, Tel: +1 (204) 958-7700 businesses and policy-makers. Website: www.iisd.org Twitter: @IISD_news IISD is registered as a charitable organization in Canada and has 501(c)(3) status in the United States. IISD receives core operating support from the Government of Canada, provided through the International Development Research Centre (IDRC) and from the Province -

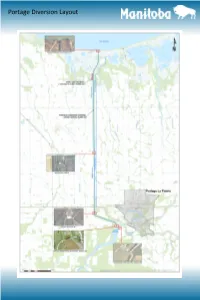

Portage Diversion Layout Recent and Future Projects

Portage Diversion Layout Recent and Future Projects Assiniboine River Control Structure Public and worker safety improvements Completed in 2015 Works include fencing, signage, and safety boom Electrical and mechanical upgrades Ongoing Works include upgrades to 600V electrical distribution system, replacement of gate control system and mo- tor control center, new bulkhead gate hoist, new stand-by diesel generator fuel/piping system and new ex- terior diesel generator Portage Diversion East Outside Drain Reconstruction of 18 km of drain Completed in 2013 Replacement of culverts beneath three (3) railway crossings Completed in 2018 Recent and Future Projects Portage Diversion Outlet Structure Construction of temporary rock apron to stabilize outlet structure Completed in 2018 Conceptual Design for options to repair or replace structure Completed in 2018 Outlet structure major repair or replacement prioritized over next few years Portage Diversion Channel Removal of sedimentation within channel Completed in 2017 Groundwater/soil salinity study for the Portage Diversion Ongoing—commenced in 2016 Enhancement of East Dike north of PR 227 to address freeboard is- sues at design capacity of 25,000 cfs Proposed to commence in 2018 Multi-phase over the next couple of years Failsafe assessment and potential enhancement of West Dike to han- dle design capacity of 25,000 cfs Prioritized for future years—yet to be approved Historical Operating Guidelines Portage Diversion Operating Guidelines 1984 Red River Floodway Program of Operation Operation Objectives The Portage Diversion will be operated to meet these objectives: 1. To provide maximum benefits to the City of Winnipeg and areas along the Assiniboine River downstream of Portage la Prairie.