285(1) a Contribution to the Morphology and Phylogeny

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Disaggregation of Bird Families Listed on Cms Appendix Ii

Convention on the Conservation of Migratory Species of Wild Animals 2nd Meeting of the Sessional Committee of the CMS Scientific Council (ScC-SC2) Bonn, Germany, 10 – 14 July 2017 UNEP/CMS/ScC-SC2/Inf.3 DISAGGREGATION OF BIRD FAMILIES LISTED ON CMS APPENDIX II (Prepared by the Appointed Councillors for Birds) Summary: The first meeting of the Sessional Committee of the Scientific Council identified the adoption of a new standard reference for avian taxonomy as an opportunity to disaggregate the higher-level taxa listed on Appendix II and to identify those that are considered to be migratory species and that have an unfavourable conservation status. The current paper presents an initial analysis of the higher-level disaggregation using the Handbook of the Birds of the World/BirdLife International Illustrated Checklist of the Birds of the World Volumes 1 and 2 taxonomy, and identifies the challenges in completing the analysis to identify all of the migratory species and the corresponding Range States. The document has been prepared by the COP Appointed Scientific Councilors for Birds. This is a supplementary paper to COP document UNEP/CMS/COP12/Doc.25.3 on Taxonomy and Nomenclature UNEP/CMS/ScC-Sc2/Inf.3 DISAGGREGATION OF BIRD FAMILIES LISTED ON CMS APPENDIX II 1. Through Resolution 11.19, the Conference of Parties adopted as the standard reference for bird taxonomy and nomenclature for Non-Passerine species the Handbook of the Birds of the World/BirdLife International Illustrated Checklist of the Birds of the World, Volume 1: Non-Passerines, by Josep del Hoyo and Nigel J. Collar (2014); 2. -

A Multi-Gene Phylogeny of Aquiline Eagles (Aves: Accipitriformes) Reveals Extensive Paraphyly at the Genus Level

Available online at www.sciencedirect.com MOLECULAR SCIENCE•NCE /W\/Q^DIRI DIRECT® PHYLOGENETICS AND EVOLUTION ELSEVIER Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 35 (2005) 147-164 www.elsevier.com/locate/ympev A multi-gene phylogeny of aquiline eagles (Aves: Accipitriformes) reveals extensive paraphyly at the genus level Andreas J. Helbig'^*, Annett Kocum'^, Ingrid Seibold^, Michael J. Braun^ '^ Institute of Zoology, University of Greifswald, Vogelwarte Hiddensee, D-18565 Kloster, Germany Department of Zoology, National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution, 4210 Silver Hill Rd., Suitland, MD 20746, USA Received 19 March 2004; revised 21 September 2004 Available online 24 December 2004 Abstract The phylogeny of the tribe Aquilini (eagles with fully feathered tarsi) was investigated using 4.2 kb of DNA sequence of one mito- chondrial (cyt b) and three nuclear loci (RAG-1 coding region, LDH intron 3, and adenylate-kinase intron 5). Phylogenetic signal was highly congruent and complementary between mtDNA and nuclear genes. In addition to single-nucleotide variation, shared deletions in nuclear introns supported one basal and two peripheral clades within the Aquilini. Monophyly of the Aquilini relative to other birds of prey was confirmed. However, all polytypic genera within the tribe, Spizaetus, Aquila, Hieraaetus, turned out to be non-monophyletic. Old World Spizaetus and Stephanoaetus together appear to be the sister group of the rest of the Aquilini. Spiza- stur melanoleucus and Oroaetus isidori axe nested among the New World Spizaetus species and should be merged with that genus. The Old World 'Spizaetus' species should be assigned to the genus Nisaetus (Hodgson, 1836). The sister species of the two spotted eagles (Aquila clanga and Aquila pomarina) is the African Long-crested Eagle (Lophaetus occipitalis). -

Life History Account for Peregrine Falcon

California Wildlife Habitat Relationships System California Department of Fish and Wildlife California Interagency Wildlife Task Group PEREGRINE FALCON Falco peregrinus Family: FALCONIDAE Order: FALCONIFORMES Class: AVES B129 Written by: C. Polite, J. Pratt Reviewed by: L. Kiff Edited by: L. Kiff DISTRIBUTION, ABUNDANCE, AND SEASONALITY Very uncommon breeding resident, and uncommon as a migrant. Active nesting sites are known along the coast north of Santa Barbara, in the Sierra Nevada, and in other mountains of northern California. In winter, found inland throughout the Central Valley, and occasionally on the Channel Islands. Migrants occur along the coast, and in the western Sierra Nevada in spring and fall. Breeds mostly in woodland, forest, and coastal habitats. Riparian areas and coastal and inland wetlands are important habitats yearlong, especially in nonbreeding seasons. Population has declined drastically in recent years (Thelander 1975,1976); 39 breeding pairs were known in California in 1981 (Monk 1981). Decline associated mostly with DDE contamination. Coastal population apparently reproducing poorly, perhaps because of heavier DDE load received from migrant prey. The State has established 2 ecological reserves to protect nesting sites. A captive rearing program has been established to augment the wild population, and numbers are increasing (Monk 1981). SPECIFIC HABITAT REQUIREMENTS Feeding: Swoops from flight onto flying prey, chases in flight, rarely hunts from a perch. Takes a variety of birds up to ducks in size; occasionally takes mammals, insects, and fish. In Utah, Porter and White (1973) reported that 19 nests averaged 5.3 km (3.3 mi) from the nearest foraging marsh, and 12.2 km (7.6 mi) from the nearest marsh over 130 ha (320 ac) in area. -

Tinamiformes – Falconiformes

LIST OF THE 2,008 BIRD SPECIES (WITH SCIENTIFIC AND ENGLISH NAMES) KNOWN FROM THE A.O.U. CHECK-LIST AREA. Notes: "(A)" = accidental/casualin A.O.U. area; "(H)" -- recordedin A.O.U. area only from Hawaii; "(I)" = introducedinto A.O.U. area; "(N)" = has not bred in A.O.U. area but occursregularly as nonbreedingvisitor; "?" precedingname = extinct. TINAMIFORMES TINAMIDAE Tinamus major Great Tinamou. Nothocercusbonapartei Highland Tinamou. Crypturellus soui Little Tinamou. Crypturelluscinnamomeus Thicket Tinamou. Crypturellusboucardi Slaty-breastedTinamou. Crypturellus kerriae Choco Tinamou. GAVIIFORMES GAVIIDAE Gavia stellata Red-throated Loon. Gavia arctica Arctic Loon. Gavia pacifica Pacific Loon. Gavia immer Common Loon. Gavia adamsii Yellow-billed Loon. PODICIPEDIFORMES PODICIPEDIDAE Tachybaptusdominicus Least Grebe. Podilymbuspodiceps Pied-billed Grebe. ?Podilymbusgigas Atitlan Grebe. Podicepsauritus Horned Grebe. Podicepsgrisegena Red-neckedGrebe. Podicepsnigricollis Eared Grebe. Aechmophorusoccidentalis Western Grebe. Aechmophorusclarkii Clark's Grebe. PROCELLARIIFORMES DIOMEDEIDAE Thalassarchechlororhynchos Yellow-nosed Albatross. (A) Thalassarchecauta Shy Albatross.(A) Thalassarchemelanophris Black-browed Albatross. (A) Phoebetriapalpebrata Light-mantled Albatross. (A) Diomedea exulans WanderingAlbatross. (A) Phoebastriaimmutabilis Laysan Albatross. Phoebastrianigripes Black-lootedAlbatross. Phoebastriaalbatrus Short-tailedAlbatross. (N) PROCELLARIIDAE Fulmarus glacialis Northern Fulmar. Pterodroma neglecta KermadecPetrel. (A) Pterodroma -

Systematics and Conservation of the Hook-Billed Kite Including the Island Taxa from Cuba and Grenada J

Animal Conservation. Print ISSN 1367-9430 Systematics and conservation of the hook-billed kite including the island taxa from Cuba and Grenada J. A. Johnson1,2, R. Thorstrom1 & D. P. Mindell2 1 The Peregrine Fund, Boise, ID, USA 2 Department of Ecology & Evolutionary Biology, University of Michigan Museum of Zoology, Ann Arbor, MI, USA Keywords Abstract phylogenetics; coalescence; divergence; conservation; cryptic species; Chondrohierax. Taxonomic uncertainties within the genus Chondrohierax stem from the high degree of variation in bill size and plumage coloration throughout the geographic Correspondence range of the single recognized species, hook-billed kite Chondrohierax uncinatus. Jeff A. Johnson, Department of Ecology & These uncertainties impede conservation efforts as local populations have declined Evolutionary Biology, University of Michigan throughout much of its geographic range from the Neotropics in Central America Museum of Zoology, 1109 Geddes Avenue, to northern Argentina and Paraguay, including two island populations on Cuba Ann Arbor, MI 48109, USA. and Grenada, and it is not known whether barriers to dispersal exist between any Email: [email protected] of these areas. Here, we present mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA; cytochrome B and NADH dehydrogenase subunit 2) phylogenetic analyses of Chondrohierax, with Received 2 December 2006; accepted particular emphasis on the two island taxa (from Cuba, Chondrohierax uncinatus 20 April 2007 wilsonii and from Grenada, Chondrohierax uncinatus mirus). The mtDNA phylo- genetic results suggest that hook-billed kites on both islands are unique; however, doi:10.1111/j.1469-1795.2007.00118.x the Cuban kite has much greater divergence estimates (1.8–2.0% corrected sequence divergence) when compared with the mainland populations than does the Grenada hook-billed kite (0.1–0.3%). -

Birds of Prey (Accipitriformes and Falconiformes) of Serra De Itabaiana National Park, Northeastern Brazil

Acta Brasiliensis 4(3): 156-160, 2020 Original Article http://revistas.ufcg.edu.br/ActaBra http://dx.doi.org/10.22571/2526-4338416 Birds of prey (Accipitriformes and Falconiformes) of Serra de Itabaiana National Park, Northeastern Brazil Cleverton da Silvaa* i , Cristiano Schetini de Azevedob i , Juan Ruiz-Esparzac i , Adauto de Souza d i Ribeiro h a Programa de Pós-Graduação em Desenvolvimento e Meio Ambiente, Universidade Federal de Sergipe, Aracajú, São Cristóvão, 49100-100, Sergipe, Brasil. *[email protected] b Programa de Pós-Graduação em Ecologia de Biomas Tropicais, Universidade Federal de Ouro Preto, Ouro Preto, 35400-000, Minas Gerais, Brasil. c Universidade Federal de Sergipe, Nossa Senhora da Glória, 49680-000, Sergipe, Brasil. d Universidade Federal de Sergipe, Aracajú, São Cristóvão, 49100-100, Sergipe, Brasil. Received: June 20, 2020 / Accepted: August 27, 2020/ Published online: September 28, 2020 Abstract Birds of prey are important for maintaining ecosystems, since they can regulate the populations of vertebrates and invertebrates. However, anthropic activities, like habitat fragmentation, have been decreasing the number of birds of prey, affecting the habitat ecological relations and, decreasing biodiversity. Our objective was to evaluate species of birds of prey (Accipitriformes and Falconiformes) in a protected area of the Atlantic forest in northeastern Brazil. The area was sampled for 17 months using fixed points and walking along a pre-existing trail. Birds of prey were classified by their Punctual Abundance Index, threat status and forest dependence. Sixteen birds of prey were recorded, being the most common Rupornis magnirostris and Caracara plancus. Most species were considered rare in the area and not dependent of forest vegetation. -

An Early Pleistocene Eagle from Nebraska

248 SHORT COMMUNICATIONS kunthii blossoms by Bombus queens occurred and depend on many factors. That hummingbirds and the workers were unable to secure nectar while positioned ancestor of P. kunthii co-existed may be assumed; within the floral tube, probably as much as lo-20 otherwise its adaptation to hummingbird pollination per cent more nectar was available to Bombus p&her would make little sense. Thus it is possible that P. and Bombus trinominatus populations during this kunthii could have undergone much of its development period due to the feeding activity of Diglossa. under selective pressure from hummingbirds; still, it is clear that Diglossa baritula has co-existed with DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSIONS hummingbirds throughout New World montane hab- Grant and Grant (1968) have proposed an explanation itats for some time and therefore an earlier and more for the reciprocal evolution of hummingbirds and the important role in the evolution of P. kunthii would plants upon which they feed. According to this inter- not be unexpected. This is not to suggest that exploita- pretation most hummingbird-pollinated flowers, espe- tion late in the evolutionary development of P. kunthii cially temperate species, have evolved from bee flowers would be insignificant. Even at present, given the (Grant 1961; Grant and Grant 1965). The process potential counter-selection pressures on P. kunthii involves an incipient stage during which a primitive from bees, the presence of Dglossa perforations un- hummingbird or progenitor already “preadapted” to doubtedly precludes a certain amount of bee pollina- feed on a particular bee flower (in the sense of tion which would probably otherwise occur, helping securing insects within the corolla, or nectar, or both), to maintain the selection pressures on P. -

Olfactory Sensitivity of the Turkey Vulture (Cathartes Aura) to Three Carrion-Associated Odorants

OLFACTORY SENSITIVITY OF THE TURKEY VULTURE (CATHARTES AURA) TO THREE CARRION-ASSOCIATED ODORANTS STEVEN A. SMITH • AND RICHARD A. PASELK Departmentsof BiologicalSciences and Chemistry, Humboldt State University, Arcata,California 95523 USA ABSTRACT.--TheTurkey Vulture (Cathartesaura) is generally thought to rely on olfactory cuesto locate carrion. Becausevertically rising odorantsare dispersedrapidly by wind tur- bulence, we predict that Turkey Vultures should be highly sensitive to these chemicalsto detect them at foraging altitudes. Olfactory thresholdsto three by-productsof animal decomposition(1 x 10-6 M for buta- noic acid and ethanethiol, and 1 x 10-5 M for trimethylamine) were determined from heart- rate responses.These relatively high thresholds indicate that these odorantsare probably not cuesfor foraging Turkey Vultures. Odorant thresholds,food habits of Turkey Vultures, and the theoretical properties of odorant dispersion cast some doubt on the general impor- tanceof olfaction in food locationby this species.Received 23 September1985, accepted 3 March 1986. THEsensory modality by which Turkey Vul- Companydiscovered that natural gas leaks could tures (Cathartes aura) locate carrion has been be tracedby injectingethanethiol into gaslines debatedby naturalistsfor nearly 140 years(see and patrolling the lines for Turkey Vultures Stager1964 for review). Most of the controver- that, ostensibly,were attractedto the metcap- sy concernedwhether olfaction or vision was tan (Stager 1964). Stager (1964: 56) concluded the more important sense,although other the- from anatomical examinations and field tests ories included an "occult" sense (Beck 1920), that the Turkey Vulture "possessesand utilizes the noiseof carrion-eatingrodents, or the noise a well developedolfactory food locatingmech- of carrion-eatinginsects (Taber 1928, Darling- anism." ton 1930) as attractingTurkey Vultures to their If Turkey Vulturesrely on olfactorycues to prey. -

Visual Adaptations of Diurnal and Nocturnal Raptors

Seminars in Cell and Developmental Biology 106 (2020) 116–126 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Seminars in Cell & Developmental Biology journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/semcdb Review Visual adaptations of diurnal and nocturnal raptors T Simon Potiera, Mindaugas Mitkusb, Almut Kelbera,* a Lund Vision Group, Department of Biology, Lund University, Sölvegatan 34, S-22362 Lund, Sweden b Institute of Biosciences, Life Sciences Center, Vilnius University, Saulėtekio Av 7, LT-10257 Vilnius, Lithuania HIGHLIGHTS • Raptors have large eyes allowing for high absolute sensitivity in nocturnal and high acuity in diurnal species. • Diurnal hunters have a deep central and a shallow temporal fovea, scavengers only a central and owls only a temporal fovea. • The spatial resolution of some large raptor species is the highest known among animals, but differs highly among species. • Visual fields of raptors reflect foraging strategies and depend on the divergence of optical axes and on headstructures • More comparative studies on raptor retinae (preferably with non-invasive methods) and on visual pathways are desirable. ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Keywords: Raptors have always fascinated mankind, owls for their highly sensitive vision, and eagles for their high visual Pecten acuity. We summarize what is presently known about the eyes as well as the visual abilities of these birds, and Fovea point out knowledge gaps. We discuss visual fields, eye movements, accommodation, ocular media transmit- Resolution tance, spectral sensitivity, retinal anatomy and what is known about visual pathways. The specific adaptations of Sensitivity owls to dim-light vision include large corneal diameters compared to axial (and focal) length, a rod-dominated Visual field retina and low spatial and temporal resolution of vision. -

Uncorrected Proof

Policy and Practice UNCORRECTED PROOF BBarney_C011.inddarney_C011.indd 117979 99/13/2008/13/2008 44:11:24:11:24 PPMM UNCORRECTED PROOF BBarney_C011.inddarney_C011.indd 118080 99/13/2008/13/2008 44:11:24:11:24 PPMM Copy edited by Richard Beatty 11 Conservation Values from Falconry Robert E. Kenward Anatrack Ltd and IUCN-SSC European Sustainable Use Specialist Group, Wareham, UK Introduction Falconry is a type of recreational hunting. This chapter considers the conser- vation issues surrounding this practice. It provides a historical background and then discusses how falconry’s role in conservation has developed and how it could grow in the future. Falconry, as defi ned by the International Association for Falconry and Conservation of Birds of Prey (IAF), is the hunting art of taking quarry in its natural state and habitat with birds of prey. Species commonly used for hunt- ing include eagles of the genera Aquila and Hieraëtus, other ‘broad-winged’ members of the Accipitrinae including the more aggressive buzzards and their relatives, ‘short-winged’ hawks of the genus Accipiter and ‘long-winged’ falcons (genus Falco). Falconers occur in more than 60 countries worldwide, mostly in North America, the Middle East, Europe, Central Asia, Japan and southern Africa. Of these countries, 48 are members of the IAF. In the European Union falconry Recreational Hunting, Conservation and Rural Livelihoods: Science and Practice, 1st edition. Edited by B. Dickson, J. Hutton and B. Adams. © 2009 Blackwell Publishing, UNCORRECTEDISBN 978-1-4051-6785-7 (pb) and 978-1-4051-9142-5 (hb). PROOF BBarney_C011.inddarney_C011.indd 118181 99/13/2008/13/2008 44:11:24:11:24 PPMM Copy edited by Richard Beatty 182 ROBERT E. -

Avian Taxonomy

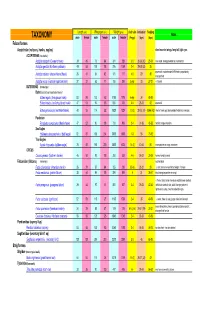

Length (cm) Wing span (cm) Weight (gms) cluch size incubation fledging Notes TAXONOMY male female male female male female (# eggs) (days) (days) Falconiformes Accipitridae (vultures, hawks, eagles) short rounded wings; long tail; light eyes ACCIPITRINAE (true hawks) Accipiter cooperii (Cooper's hawk) 39 45 73 84 341 528 3-5 30-36 (30) 25-34 crow sized; strongly banded tail; rounded tail Accipiter gentilis (Northern goshawk) 49 58 101 108 816 1059 2-4 28-38 (33) 35 square tail; most abundant NAM hawk; proportionaly 26 31 54 62 101 177 4-5 29 30 Accipiter striatus (sharp-shinned hawk) strongest foot Accipiter nisus (Eurasian sparrowhawk ) 37 37 62 77 150 290 5-Apr 33 27-31 Musket BUTEONINAE (broadwings) Buteo (buzzards or broad tailed hawks) Buteo regalis (ferruginous hawk) 53 59 132 143 1180 1578 6-Apr 34 45-50 Buteo lineatus (red-shouldered hawk) 47 53 96 105 550 700 3-4 28-33 42 square tail Buteo jamaicensis (red-tailed hawk) 48 55 114 122 1028 1224 1-3 (3) 28-35 (34) 42-46 (42) (Harlan' hawk spp); dark patagial featehres: immature; Parabuteo Parabuteo cuncincutus (Harris hawk) 47 52 90 108 710 890 2-4 31-36 45-50 reddish orange shoulders Sea Eagles Haliaeetus leucocephalus (bald eagle) 82 87 185 244 3000 6300 1-3 35 70-92 True Eagles Aquila chrysaetos (golden eagle) 78 82 185 220 3000 6125 1-4 (2) 40-45 50 white patches on wings: immature; CIRCUS Circus cyaneus (Northern harrier) 46 50 93 108 350 530 4-6 26-32 30-35 hovers; hunts by sound Falconidae (falcons) (longwings) notched beak Falco columbarius (American merlin) 26 29 57 64 -

Birds of Gus Engeling Wildlife Management Area

TEXAS PARKS AND WILDLIFE BIRDS OF G U S E N G E L I N G WILDLIFE MANAGEMENT AREA A FIELD CHECKLIST “Act Natural” Visit a Wildlife Management Area at our Web site: http://www.tpwd.state.tx.us Cover: Illustration of Pileated Woodpecker by Rob Fleming. HABITAT DESCRIPTION he Gus Engeling Wildlife Management Area is located in the northwest corner of Anderson County, 20 miles Tnorthwest of Palestine, Texas, on U.S. Highway 287. The management area contains 10,958 acres of land owned by the Texas Parks and Wildlife Department. Most of the land was purchased in 1950 and 1951, with the addition of several smaller tracts through 1960. It was originally called the Derden Wildlife Management Area, but was later changed to the Engeling Wildlife Management Area in honor of Biologist Gus A. Engeling, who was killed by a poacher on the area in December 1951. The area is drained by Catfish Creek which is a tributary of the Trinity River. The topography is gently rolling to hilly, with a well-defined drainage system that empties into Catfish Creek. Most of the small streams are spring fed and normally flow year-round. The soils are mostly light colored, rapidly permeable sands on the upland, and moderately permeable, gray-brown, sandy loams in the bottomland along Catfish Creek. The climate is classified as moist, sub-humid, with an annual rainfall of about 40 inches. The vegetation consists of deciduous forest with an overstory made up of oak, hickory, sweetgum and elm; with associated understory species of dogwood, American beautyberry, huckleberry, greenbrier, etc.