View on the Mainland That “Global Opinion [Was] Stacked Against Them” 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Uva-DARE (Digital Academic Repository)

UvA-DARE (Digital Academic Repository) Red Sonic Trajectories - Popular Music and Youth in China de Kloet, J. Publication date 2001 Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): de Kloet, J. (2001). Red Sonic Trajectories - Popular Music and Youth in China. General rights It is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), other than for strictly personal, individual use, unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Disclaimer/Complaints regulations If you believe that digital publication of certain material infringes any of your rights or (privacy) interests, please let the Library know, stating your reasons. In case of a legitimate complaint, the Library will make the material inaccessible and/or remove it from the website. Please Ask the Library: https://uba.uva.nl/en/contact, or a letter to: Library of the University of Amsterdam, Secretariat, Singel 425, 1012 WP Amsterdam, The Netherlands. You will be contacted as soon as possible. UvA-DARE is a service provided by the library of the University of Amsterdam (https://dare.uva.nl) Download date:08 Oct 2021 L4Trif iÏLK m BEGINNINGS 0 ne warm summer night in 1991, I was sitting in my apartment on the 11th floor of a gray, rather depressive building on the outskirts of Amsterdam, when a documentary on Chinese rock music came on the TV. I was struck by the provocative poses of Cui Jian, who blindfolded himself with a red scarf - stunned by the images of the crowds attending his performance, images that were juxtaposed with accounts of the student protests of June 1989; and puzzled, as I, a rather distant observer, always imagined China to be a totalitarian regime with little room for dissident voices. -

Pop Songs Between 1930S and 1940S in Shanghai”—Aesthetic Release of Eros Utopia

Journal of Literature and Art Studies, December 2016, Vol. 6, No. 12, 1545-1548 doi: 10.17265/2159-5836/2016.12.010 D DAVID PUBLISHING Behind “Pop Songs Between 1930s and 1940s in Shanghai”—Aesthetic Release of Eros Utopia ZHOU Xiaoyan Yancheng Institute of Technology, Jiangsu, China CANG Kaiyan, ZHOU Hanlu Jiangsu Yancheng Middle School, Jiangsu, China “Pop Songs between 1930s and 1940s in Shanghai” contains the artistic phenomenon with the utopian feature. Its main objective lies in the will instead of hope. The era endows different aesthetic utopian meanings to “Pop Songs between 1930s and 1940s in Shanghai”. After 2010, the utopian change of such songs is closely related to the contradiction between “aesthetic imagination and reality”, and “individual interest and integrated social interest” that are intrinsic in the utopian concept. To sort out the utopian process of those songs, it is helpful for correcting the current status about the weakened critical realism function of the current art, and accelerating the arousal of the literary and artistic creation, and individual consciousness, laying equal stress on and gathering the aesthetic power of these individuals, which provides solid foundation for the generalization of aesthetic utopian significance. Keywords: Shanghai Oldies (Pop Songs between 1930s and 1940s in Shanghai), aesthetic utopia, internal contradiction Introduction “Shanghai Oldies” refers to the pop songs that were produced and popular in Shanghai, sung widely over the country from 1930s to 1940s. It presents the graceful charm related to the south of the Yangtze River between grace and joy feature. It not only shows the memory of metropolis (invested with foreign adventures) in Old Shanghai, but also creates “Eros Utopia” based on presenting the ordinary love, instead of perfect political institution planning. -

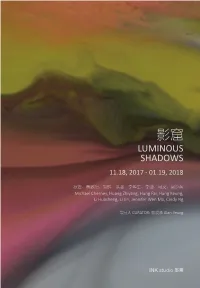

影窟 Luminous Shadows 11.18, 2017 - 01.19, 2018

影窟 LUMINOUS SHADOWS 11.18, 2017 - 01.19, 2018 秋麦、黄致阳、熊辉、洪强、李华生、李津、马文、吴少英 Michael Cherney, Huang Zhiyang, Hung Fai, Hung Keung, Li Huasheng, Li Jin, Jennifer Wen Ma, Cindy Ng 策展人 CURATOR: 杨浚承 Alan Yeung 影窟 LUMINOUS SHADOWS 11.18, 2017 - 01.19, 2018 秋麦、黄致阳、熊辉、洪强、李华生、李津、马文、吴少英 Michael Cherney, Huang Zhiyang, Hung Fai, Hung Keung, Li Huasheng, Li Jin, Jennifer Wen Ma, Cindy Ng 策展人 CURATOR: 杨浚承 Alan Yeung Contents 006 展览介绍 Introduction 006 杨浚承 Alan Yeung 006 作品 Works 010 006 秋麦 Michael Cherney 010 黄致阳 Huang Zhiyang 026 熊辉 Hung Fai 050 洪强 Hung Keung 076 李华生 Li Huasheng 084 李津 Li Jin 112 马文 Jennifer Wen Ma 150 吴少英 Cindy Ng 158 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any other information storage and retrieval system, without written permission from Ink Studio. © 2017 Ink Studio Artworks © 1981-2017 The Artists (Front Cover Image 封面图片 ) 吴少英 Cindy NG | Sea of Flowers 花海 (detail 局部 ) | P116 (Back Cover Image 封底图片 ) 李津 Li Jin | The Hungry Tigress 舍身饲虎 (detail 局部 ) | P162 6 7 INTRODUCTION Alan Yeung A painted rock bleeds as living flesh across sheets of paper. A quivering line In Jennifer Wen Ma’s (b. 1970, Beijing) installation, light and glass repeatedly gives form to the nuances of meditative experience. The veiled light of an coalesce into an illusionary landscape before dissolving in a reflective ink icon radiates through the near-instantaneous marks by a pilgrim’s hand. -

Contemporary China: a Book List

PRINCETON UNIVERSITY: Woodrow Wilson School, Politics Department, East Asian Studies Program CONTEMPORARY CHINA: A BOOK LIST by Lubna Malik and Lynn White Winter 2007-2008 Edition This list is available on the web at: http://www.princeton.edu/~lynn/chinabib.pdf which can be viewed and printed with an Adobe Acrobat Reader. Variation of font sizes may cause pagination to differ slightly in the web and paper editions. No list of books can be totally up-to-date. Please surf to find further items. Also consult http://www.princeton.edu/~lynn/chinawebs.doc for clicable URLs. This list of items in English has several purposes: --to help advise students' course essays, junior papers, policy workshops, and senior theses about contemporary China; --to supplement the required reading lists of courses on "Chinese Development" and "Chinese Politics," for which students may find books to review in this list; --to provide graduate students with a list that may suggest books for paper topics and may slightly help their study for exams in Chinese politics; a few of the compiler's favorite books are starred on the list, but not much should be made of this because such books may be old or the subjects may not meet present interests; --to supplement a bibliography of all Asian serials in the Princeton Libraries that was compiled long ago by Frances Chen and Maureen Donovan; many of these are now available on the web,e.g., from “J-Stor”; --to suggest to book selectors in the Princeton libraries items that are suitable for acquisition; to provide a computerized list on which researchers can search for keywords of interests; and to provide a resource that many teachers at various other universities have also used. -

Cc6fe371d11541538bd242467c

On February 24, 2018, Henan: Home of Chinese Culture—2018 Hong Kong Happy Spring New Year Temple Fair was grandly opened in Kowloon Park in Hong Kong. On February 18, 2018, Home of Panda: Beautiful Sichuan—The Eighth Cross-Straits Spring Festival Folk Temple Fair was grandly opened at the Nantou County Convention and Exhibition Center in Taiwan. On February 2, 2018, Universal Celebrations—the People of China and the Philippines jointly welcome the New Year was held at the Commercial Center in Clarke, the Philippines. On February 22, 2018, the celebration of 2018 EU-China Tourism Year—Chinese Lanterns Light up the heart of Europe was successfully held in the Grand Place in Brussels, Belgium. Contents Express News FOCUS 04 President Li Xiaolin meets with Cambodian group /Wang Bo 04 Vice-President Xie Yuan meets granddaughter of General Chennault /Jin Hanghang 05 Vice-President Hu Sishe attends premiere of documentary film, TCM promotion tour /Yu Xiaodong 05 20th anniversary of China-South Africa diplomatic ties /Zhang Yujun 06 China-Japan friendship concert held in Beijing /Liu Mengyan 04 06 President Li Xiaolin and Secretary-General Li Xikui attend signing ceremony /Jia Ji 07 International sister city exchanges exhibition /Chengdu Friendship Association 07 The Belt and Road: 2018 Walk into Nepal photography competition / Chengdu Friendship Association 21 View 08 Kimiyo Matsuzaki, witness of ping-pong diplomacy between China and Japan /He Yan 12 The legendary life of He Lianxiang, goodwill messenger of Peru-China 36 friendship /Tang Mingxin -

Integrating Chinese and Western Pursuit of Excellence

2021 4th International Workshop on Advances in Social Sciences (IWASS 2021) Integrating Chinese and Western Pursuit of Excellence Jing Zeng1, Huijun Shen2 1Arts College of Sichuan University, PhD student 2College of Forestry, Sichuan Agricultural University, Wenjiang 611130, China Keywords: Shanghai furniture, Chinese and western combination, “innovation and progress” Abstract: “ShangHai furniture” was born under the combined effect of the localization of Western-style furniture and the westernization of faithful furniture. It is the most representative fusion of China and the West. This article analyzes the contribution of “Shanghai style furniture” to the fusion of Chinese and Western furniture and its positive effect on China's modern furniture innovation based on the four stages of “Shanghai style furniture”: “germination”, “development”, “rejuvenation” and “innovation”. 1. Introduction ShangHai furniture is the product of ShangHai culture, which generally refers to the combination of Chinese and Western style furniture. It is a combination of the advantages of Western-style furniture. During the Republic of China, the beach was born and the place where all the nations came together, thus forming this vast and profound furniture. Shanghai style furniture is the product of the collision between Chinese and Western cultures, and it is partially integrated, so it has dual characteristics of Chinese and Western cultures. Although it is ordinary daily necessities, it is the bearer of China's historical culture. Since ancient times, the Chinese nation has firmly believed in the idea of “harmony and difference” and “tolerance is greater”. Among the furniture, no one can better interpret the harmony culture than Shanghai furniture. Therefore, since its birth, it has become the spokesperson for the fusion of Chinese and Western furniture. -

Westernisation, Ideology and National Identity in 20Th-Century Chinese Music

Westernisation, Ideology and National Identity in 20th-Century Chinese Music Yiwen Ouyang PhD Thesis Royal Holloway, University of London DECLARATION OF AUTHORSHIP I, Yiwen Ouyang, hereby declare that this thesis and the work presented in it is entirely my own. Where I have consulted the work of others, this is always clearly stated. Signed: Date: 19 May 2012 I To my newly born baby II ABSTRACT The twentieth century saw the spread of Western art music across the world as Western ideology and values acquired increasing dominance in the global order. How did this process occur in China, what complexities does it display and what are its distinctive features? This thesis aims to provide a detailed and coherent understanding of the Westernisation of Chinese music in the 20th century, focusing on the ever-changing relationship between music and social ideology and the rise and evolution of national identity as expressed in music. This thesis views these issues through three crucial stages: the early period of the 20th century which witnessed the transition of Chinese society from an empire to a republic and included China’s early modernisation; the era from the 1930s to 1940s comprising the Japanese intrusion and the rising of the Communist power; and the decades of economic and social reform from 1978 onwards. The thesis intertwines the concrete analysis of particular pieces of music with social context and demonstrates previously overlooked relationships between these stages. It also seeks to illustrate in the context of the appropriation of Western art music how certain concepts acquired new meanings in their translation from the European to the Chinese context, for example modernity, Marxism, colonialism, nationalism, tradition, liberalism, and so on. -

Shanghai Before Nationalism Yexiaoqing

East Asian History NUMBER 3 . JUNE 1992 THE CONTINUATION OF Papers on Fa r EasternHistory Institute of Advanced Studies Australian National University Editor Geremie Barme Assistant Editor Helen 1.0 Editorial Board John Clark Igor de Rachewiltz Mark Elvin (Convenor) Helen Hardacre John Fincher Colin Jeffcott W.J.F. Jenner 1.0 Hui-min Gavan McCormack David Marr Tessa Morris-Suzuki Michael Underdown Business Manager Marion Weeks Production Oahn Collins & Samson Rivers Design Maureen MacKenzie, Em Squared Typographic Design Printed by Goanna Print, Fyshwick, ACT This is the second issue of EastAsian History in the series previously entitled Papers on Far Eastern History. The journal is published twice a year. Contributions to The Editor, EastAsian History Division of Pacific and Asian History, Research School of Pacific Studies Australian National University, Canberra ACT 2600, Australia Phone +61-6-2493140 Fax +61-6-2571893 Subscription Enquiries Subscription Manager, East Asian History, at the above address Annual Subscription Rates Australia A$45 Overseas US$45 (for two issues) iii CONTENTS 1 Politics and Power in the Tokugawa Period Dani V. Botsman 33 Shanghai Before Nationalism YeXiaoqing 53 'The Luck of a Chinaman' : Images of the Chinese in Popular Australian Sayings Lachlan Strahan 77 The Interactionistic Epistemology ofChang Tung-sun Yap Key-chong 121 Deconstructing Japan' Amino Yoshthtko-translat ed by Gavan McCormack iv Cover calligraphy Yan Zhenqing ���Il/I, Tang calligrapher and statesman Cover illustration Kazai*" -a punishment -

The Politics Underlying the Art Movements in China During Two Key Ten-Year Periods: {1945-1955 Liberation} and {1985-1995 Opening}

The Politics Underlying the Art Movements in China During two key Ten-year Periods: {1945-1955 Liberation} and {1985-1995 Opening} by David Harrison O'Dell [email protected] www.texasdavid.com/export/index.html Under the mentorship of Dr. Janice Leoshko The University of Texas at Austin, Department of Asian Studies Research term: Beijing, CHINA 1995-1997 Written term: Beijing, CHINA 1996-1997 Added revisions / pictures: 2000 to present (Xiao Guo Fu, Morgan) 1 Politics behind the Arts in China – David O’Dell This thesis is divided into two chronological parts that I chose as representing modern Chinese art at its most vibrant. I state now that I don't see the Cultural Revolution as containing much positive influence at all; therefore I saddle my research periods before and after it. In my opinion it seems that more people find the Cultural Revolution, a period of warped societal possession, strikingly interesting, I however do not. I personally find the Liberation period of the 1940's-the spirit that drove a burgeoning young Communist party to fight for China's independence-contrasted with the New Reform period of the 1980's-the time in which the battle for artistic independence is waged while new technologies and new ideas are assimilated into everyday life-to be incredibly insightful and ripe with valuable lessons for tomorrow's China. Part One takes the Chinese art world of the Liberation period, art being a normally "qualitative" entity, and describes it "quantitatively" through the policies issued by the CCP that steered art's path during the years preceding and following Liberation. -

Nations and Art: the Shaping of Art in Communist Regimes

NATIONS AND ART: THE SHAPING OF ART IN COMMUNIST REGIMES Lena Galperina Advisor: Patrick Thaddeus Jackson Fall 09 and Spring 10 General University Honors Galperina 1 Looking back at history, although art is not a necessity like water or food, it has always been an integral part in the development of all civilizations. So what part does it play in society and what is its impact on people? One way to look at art is to look at what guides its development and what are the results that follow. In the case of this paper, I am focusing specifically on how the arts are shaped by the political bodies that govern people, specifically focusing on Communist regimes. This is art of public nature and an integral part of all society, because it is created with the purpose of being seen by many. This of course is not something unique to the Communist regimes, or even their time period. Art has had public function throughout history, all one has to do is look at something like the Renaissance altar pieces, the drawings and carvings on the walls of Egyptian monuments or the murals commissioned in USA through the New Deal. In fact the idea of “art for art’s sake” only developed in the early 19 th century. This means that historically art has been used for a particular function, or to convey a specific idea to the viewers. This does not mean that before the 19 th century art was always done for some grand purpose, private commissions existed too of course; but artists mostly relied on patrons and the art that was available to the public was often commissioned for a purpose, and usually conveyed some sort of message. -

Post-Cold War Experimental Theatre of China: Staging Globalisation and Its Resistance

Post-Cold War Experimental Theatre of China: Staging Globalisation and Its Resistance Zheyu Wei A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The School of Creative Arts The University of Dublin, Trinity College 2017 Declaration I declare that this thesis has not been submitted as an exercise for a degree at this or any other university and it is my own work. I agree to deposit this thesis in the University’s open access institutional repository or allow the library to do so on my behalf, subject to Irish Copyright Legislation and Trinity College Library Conditions of use and acknowledgement. ___________________ Zheyu Wei ii Summary This thesis is a study of Chinese experimental theatre from the year 1990 to the year 2014, to examine the involvement of Chinese theatre in the process of globalisation – the increasingly intensified relationship between places that are far away from one another but that are connected by the movement of flows on a global scale and the consciousness of the world as a whole. The central argument of this thesis is that Chinese post-Cold War experimental theatre has been greatly influenced by the trend of globalisation. This dissertation discusses the work of a number of representative figures in the “Little Theatre Movement” in mainland China since the 1980s, e.g. Lin Zhaohua, Meng Jinghui, Zhang Xian, etc., whose theatrical experiments have had a strong impact on the development of contemporary Chinese theatre, and inspired a younger generation of theatre practitioners. Through both close reading of literary and visual texts, and the inspection of secondary texts such as interviews and commentaries, an overview of performances mirroring the age-old Chinese culture’s struggle under the unprecedented modernising and globalising pressure in the post-Cold War period will be provided. -

Involving the Community in Inner City Renewal: a Case Study of Nanluogu in Beijing

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Zhang, Chun; Lu, Bin; Song, Yan Article Involving the community in inner city renewal: A case study of Nanluogu in Beijing Journal of Urban Management Provided in Cooperation with: Chinese Association of Urban Management (CAUM), Taipei Suggested Citation: Zhang, Chun; Lu, Bin; Song, Yan (2012) : Involving the community in inner city renewal: A case study of Nanluogu in Beijing, Journal of Urban Management, ISSN 2226-5856, Elsevier, Amsterdam, Vol. 1, Iss. 2, pp. 53-71, http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S2226-5856(18)30060-8 This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/194394 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. may exercise further usage rights as specified in the indicated licence.