Do As I Say, Not As I Do

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Marketing Plan

ALLIED ARTISTS MUSIC GROUP An Allied Artists Int'l Company MARKETING & PROMOTION MARKETING PLAN: ROCKY KRAMER "FIRESTORM" Global Release Germany & Rest of Europe Digital: 3/5/2019 / Street 3/5/2019 North America & Rest of World Digital: 3/19/2019 / Street 3/19/2019 MASTER PROJECT AND MARKETING STRATEGY 1. PROJECT GOAL(S): The main goal is to establish "Firestorm" as an international release and to likewise establish Rocky Kramer's reputation in the USA and throughout the World as a force to be reckoned with in multiple genres, e.g. Heavy Metal, Rock 'n' Roll, Progressive Rock & Neo-Classical Metal, in particular. Servicing and exposure to this product should be geared toward social media, all major radio stations, college radio, university campuses, American and International music cable networks, big box retailers, etc. A Germany based advance release strategy is being employed to establish the Rocky Kramer name and bona fides within the "metal" market, prior to full international release.1 2. OBJECTIVES: Allied Artists Music Group ("AAMG"), in association with Rocky Kramer, will collaborate in an innovative and versatile marketing campaign introducing Rocky and The Rocky Kramer Band (Rocky, Alejandro Mercado, Michael Dwyer & 1 Rocky will begin the European promotional campaign / tour on March 5, 2019 with public appearances, interviews & live performances in Germany, branching out to the rest of Europe, before returning to the U.S. to kick off the global release on March 19, 2019. ALLIED ARTISTS INTERNATIONAL, INC. ALLIED ARTISTS MUSIC GROUP 655 N. Central Ave 17th Floor Glendale California 91203 455 Park Ave 9th Floor New York New York 10022 L.A. -

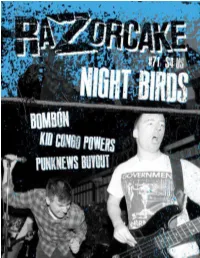

Razorcake Issue

RIP THIS PAGE OUT Curious about how to realistically help Razorcake? If you wish to donate through the mail, please rip this page out and send it to: Razorcake/Gorsky Press, Inc. PO Box 42129 Los Angeles, CA 90042 Just NAME: turn ADDRESS: the EMAIL: page. DONATION AMOUNT: 5D]RUFDNH*RUVN\3UHVV,QFD&DOLIRUQLDQRWIRUSUR¿WFRUSRUDWLRQLVUHJLVWHUHG DVDFKDULWDEOHRUJDQL]DWLRQZLWKWKH6WDWHRI&DOLIRUQLD¶V6HFUHWDU\RI6WDWHDQGKDV EHHQJUDQWHGRI¿FLDOWD[H[HPSWVWDWXV VHFWLRQ F RIWKH,QWHUQDO5HYHQXH &RGH IURPWKH8QLWHG6WDWHV,562XUWD[,'QXPEHULV <RXUJLIWLVWD[GHGXFWLEOHWRWKHIXOOH[WHQWSURYLGHGE\ODZ SUBSCRIBE AND HELP KEEP RAZORCAKE IN BUSINESS Subscription rates for a one year, six-issue subscription: U.S. – bulk: $16.50 • U.S. – 1st class, in envelope: $22.50 Prisoners: $22.50 • Canada: $25.00 • Mexico: $33.00 Anywhere else: $50.00 (U.S. funds: checks, cash, or money order) We Do Our Part www.razorcake.org Name Email Address City State Zip U.S. subscribers (sorry world, int’l postage sucks) will receive either Grabass Charlestons, Dale and the Careeners CD (No Idea) or the Awesome Fest 666 Compilation (courtesy of Awesome Fest). Although it never hurts to circle one, we can’t promise what you’ll get. Return this with your payment to: Razorcake, PO Box 42129, LA, CA 90042 If you want your subscription to start with an issue other than #72, please indicate what number. TEN NEW REASONS TO DONATE TO RAZORCAKE VPDQ\RI\RXSUREDEO\DOUHDG\NQRZRazorcake ALVDERQDILGHQRQSURILWPXVLFPDJD]LQHGHGLFDWHG WRVXSSRUWLQJLQGHSHQGHQWPXVLFFXOWXUH$OOGRQDWLRQV The Donation Incentives are… -

Persatuan Geologi Malaysia

ISSN 0126-5539 PERSATUAN GEOLOGI MALAYSIA NEWSLETTER OF THE GEOLOGICAL SOCIETY OF MALAYSIA KANDUNGAN (Contents) CATATAN GEOLOGI (Geological Notes) Robert B. Tate: A new Earth theory for the new Millennium 73 PERTEMUAN PERSATUAN (Meetings of the Society) Dynamic Stratigraphy & Tectonics of Peninsular Malaysia: Third Seminar 77 - The Mesozoic of Peninsular Malaysia - Report Programme 78 Abstracts of Papers 80 Peter Hobbs: Measurement of shrinkage limit 85 Malam Geologis Muda IIIIYoung Geologist Nite III 86 Abd. Rasid Jaapar: Soil and rock description for civil engineering 88 purposes: overview on current practice in Malaysia and the need for geological institutions involvement Tajul Anuar Jamaluddin and Mogana Sundaram: Excavatability 93 assessment of weathered rock mass - case studies from Ijok, Selangor and Kemaman, Terengganu Laporan Seminar Setengah Hari "Penggunaan Geofizik dalam Kajian 95 Geoteknik" Peter Boles: DLIS and archival of interpreted petrophysical data 97 BERITA-BERITA PERSATUAN (News of the Society) . Keahlian (Membership) 99 Pertukaran Alamat (Change of Address) 99 Current Addresses Wanted 100 Pertambahan Baru Perpustakaan (New Library Additions) 100 BERITA-BERITA LAIN (Other News) Kalendar (Calendar) 105 Majlis (Council) 2000/2001 Presiden (President) Abdul Ghani Rafek N aib Presiden (Vice-President) Mohd. Shafeea Leman Setiausaha (Secretary) Ahmad Tajuddin Ibrahim Penolong Setiausaha (Asst. Secretary) Nik Ramli Nik Hassan Bendahari (Treasurer) Lee Chai Peng Pengarang (Editor) TehGuanHoe Presiden Yang Dahulu (Immediate Past President) : Ibrahim Komoo Ahli-AhliMajli.':(~unciliors) 2000-2002 2000-2001 Abdul Rahim Samsudin Hamdan Hassan Azmi Yakzan Liew Kit Kong M. Selvarajah Mogana Sundaram Tajul Anuar Jamaluddin Tan Boon Kong Jawatankuasa Kecil Pengarang (Editorial Subcommittee) Teh Guan Hoe (Pengerusi/Chairman) Fan Ah Kwai Ng Tham Fatt J.J. -

October 19-25, 2017 FACEBOOK.COM/WHATZUPFTWAYNE • What’S Happening at Sweetwater? Artist Events, Workshops, Camps, and More!

OCTOBER 19-25, 2017 FACEBOOK.COM/WHATZUPFTWAYNE • WWW.WHATZUP.COM What’s happening at Sweetwater? Artist events, workshops, camps, and more! FREE Pro Tools Master Class OPEN MIC Roll up your sleeves and get hands-on as you learn from Pro Tools expert, and NIGHT professional recording engineer, Nathan Heironimus, right here at Sweetwater. 7–8:30PM every third Monday of the month November 9–11 | 9AM–6PM $995 per person This is a free, family-friendly, all ages event. Bring your acoustic instruments, your voice, and plenty of friends to Sweetwater’s Crescendo Club stage for a great night of local music and entertainment. Buy. Sell. Trade. Play. FREE Have some old gear and looking to upgrade? Bring it in to Sweetwater’s Gear Exchange and get 5–8PM every second and your hands on great gear and incredible prices! fourth Tuesday of the month FREE Hurry in, items move fast! Guitars • Pedals • Amps • Keyboards & More* 7–8:30PM every last Check out Gear Exchange, just inside Sweetwater. Thursday of the month DRUM CIRCLE FREE 7–8PM every first Tuesday of the month *While supplies last Don’t miss any of these events! Check out Sweetwater.com/Events to learn more and to register! Music Store Community Events Music Lessons Sweetwater.com • (260) 432-8176 • 5501 US Hwy 30 W • Fort Wayne, IN 2 ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------- www.whatzup.com ------------------------------------------------------------October 19, 2017 whatzup Volume 22, Number 12 s local kids from 8 to 80 gear up for the coming weekend’s big Fright Night activi- ties, there’s much to see and do in and around the Fort Wayne area that has noth- ing at all to do with spooks and goblins and ghouls and jack-o-lanterns. -

Popular Music, Cambridge University Press Review by Dr Andrew Branch, University of East London [email protected] Global

Popular Music, Cambridge University Press Review by Dr Andrew Branch, University of East London [email protected] Global Glam and Popular Music: Style and Spectacle from the 1970s to the 2000s. Edited by Ian Chap- man and Henry Johnson. London: Routledge, 2016. 300pp. ISBN: 978-1-138-82176-7 The cultural theorist, Jon Stratton is a key inspiration in this account of the original British Glam Rock phenomenon and a sample of its global scions since the 1970s. Subsequent to Stratton’s (1986) call for further critical work on this popular music formation, Stuart Hall (1992), in an unconnected piece, speculated on what the future of Cultural Studies, Stratton’s disciplinary home, might look like. Hall’s concern, analogous in some ways to Pierre Bourdieu’s in the context of the contemporaneous French intellectual field, was predicated on a suspicion of what he read, particularly in terms of the North American interpretation of Cultural Studies, as a troubling shift towards theoreticism, the uncoupling of theory from practice in the pursuit of the institutionalization of (sub)fields of scholarly enquiry, to adopt Bourdieu’s spatial metaphor. Hall’s plea was to embrace the ‘danger’ of the paradoxes arising from securing status (publish! career!), thus risking institutionally determined compromise, and main- taining a marginality that afforded greater autonomy - especially in terms of political agency beyond the academy - but necessarily meant forgoing a meaningful resource base, essential for agitating for social change. Popular Music Studies, in one of its intellectual trajectories a disciplinary subfield of Cultural Studies, is now well established and the authors of the 19 essays that form this collection can be forgiven the temptation to see in writing about Glam a way of securing its place within the legitimated subfield, with its attendant experts and gatekeepers, ripe for future revisiting. -

Malaysia 2020 International Religious Freedom Report

MALAYSIA 2020 INTERNATIONAL RELIGIOUS FREEDOM REPORT Executive Summary The constitution states Islam is the “religion of the Federation; but other religions may be practiced in peace and harmony.” Federal and state governments have the power to mandate doctrine for Muslims and promote Sunni Islam above all other religious groups. Other forms of Islam are illegal. Sedition laws criminalize speech that “promotes ill will, hostility, or hatred on the grounds of religion.” The government maintains a parallel legal system, with certain civil matters for Muslims covered by sharia. The relationship between sharia and civil law remains unresolved in the legal system. Individuals diverging from the official interpretation of Islam continued to face adverse government action, including mandatory “rehabilitation” in centers that teach and enforce government-approved Islamic practices. Sources stated that there was some selective persecution of non- Muslim faiths through legal and extralegal means. In February, the human rights commission (SUHAKAM) initiated a public inquiry into the 2016 disappearance of a Christian pastor and his wife. A government-appointed panel formed in 2019 to investigate SUHAKAM’s findings on the enforced disappearances of another Christian pastor and a social activist accused of spreading Shia teachings in 2016 made little progress. In February, the wife of the second Christian pastor initiated legal action against the federal government and senior officials for failing to properly investigate her husband’s disappearance. In July, the High Court convicted a man for training members of a WhatsApp group to commit terrorist acts, including attacks on a Hindu temple and other houses of worship. The Sharia High Court pursued contempt charges against a member of parliament who stated that sharia courts discriminated against women. -

Multilingual Metal Music EMERALD STUDIES in METAL MUSIC and CULTURE

Multilingual Metal Music EMERALD STUDIES IN METAL MUSIC AND CULTURE Series Editors: Rosemary Lucy Hill and Keith Kahn-Harris International Editorial Advisory Board: Andy R. Brown, Bath Spa University, UK; Amber Clifford-Napleone, University of Central Missouri, USA; Kevin Fellezs, Columbia University, USA; Cynthia Grund, University of Southern Denmark, Denmark Gérôme Guibert, Université Sorbonne Nouvelle, France; Catherine Hoad, Macquarie University, Australia; Rosemary Overell, Otago University, New Zealand; Niall Scott, University of Central Lancashire, UK; Karl Sprack- len, Leeds Beckett University, UK; Heather Savigny, De Montfort University, UK; Nelson Varas-Diaz, Florida International University, USA; Deena Wein- stein, DePaul University, USA Metal Music Studies has grown enormously over the last 8 years from a hand- ful of scholars within Sociology and Popular Music Studies, to hundreds of active scholars working across a diverse range of disciplines. The rise of interest in heavy metal academically reflects the growth of the genre as a normal or con- tested part of everyday lives around the globe. The aim of this series is to provide a home and focus for the growing number of monographs and edited collections that analyse heavy metal and other heavy music; to publish work that fits within the emergent subject field of metal music studies; that is, work that is critical and inter-disciplinary across the social sciences and humanities; to publish work that is of interest to and enhances wider disciplines and subject fields across social sciences and the humanities; and to support the development of early career researchers through providing opportunities to convert their doctoral theses into research monographs. -

Underground Power Records Releases

Underground Power Records Releases VINYL AIRCRAFT LP - Maximum Destruktion (LIM.300 - 100 col. + 200 black Vinyl) - Black Vinyl 16 € + RED Vinyl 17 € Brandnew traditional Heavy Metal Killer from Malaysia ! For Fans of NWOBHM + classic 80's Heavy Metal / Speed Metal ! After their Debut Demo in 2015 which was a blast in the Underground Metal Scene - the guys are back with their full length Debut CD in 2017 - now finally available in Vinyl ! This is the real Underground ! For Fans of Ambush, Air Raid, Enforcer, Jaguar, Cloven Hoof, Riot BATTLE AXE (US) - We're on the attack LP (LIM.300 - 100 col. + 200 black Vinyl) - Black Vinyl 16 € + BLUE Vinyl 17 € US Metal Classic from 1985 - originally released as Private Press with prices over 100 USD ! High pitched Vocals, razorsharp Guitars ! For Fans of Malice, Shok Paris, Helix, Accept, Krokus, and early Savatage CARNAGE LP - Massacre (LIM.300 - 100 col. + 200 black Vinyl) - Black Vinyl 16 € + RED Vinyl 17 € One of most wanted US Metal rarities now on high quality re-issue ! Obscure US Speed Metal from 1986 for Fans of Cirith Ungol, Sinister Angel, Brocas Helm CARNAGE from the barren wastelands of South Carolina was cranking out their own brand of speed metal. Perhaps the band where not going for any particular sound or genre, it just came out as it did, It would be raw, aggressive, organic, and totally DIY. The outcome was the bands self-titled full-length in 1986 that featured 7-tracks that could have easily been featured on any of the first five volumes of 'Metal Massacre'. -

GERMAN SCENE Importantly, Macdonald Noted That a Lot Ofnew German Music Was in Germany Until It Found Critical Favour in the UK

278 THE AMBIENT CENTURY AMBIENCE IN THE ROCK ERA 279 was a comparison. 13y 1975 Oldfield had 1973). Moreover most writers accuse the eminent British musicologist Ian returned to form with an elaborate album of instnnnental timbres MacDonald ofinventing the label during the early 19705 when he wrote about featunng Celtic harp and bodhran, Greek synthesizers, Northum German music in the New lvlusical In fact during December of 1972 brian pipes and African drumming. As with Tubular Bells, Ommadawn featured MacDonald published three articles titled 'Germany , two Sally Oldfield 011 backing vocals but expanded the contributors to of them double broadsheet pages. In not one line did he mention the term brass, and the sound of uileann pipes courtesy of The Chieftains' 'krautrock'! Moloney. Even OldfIeld's brother Terry played the pan pipes. The African Instead MacDonald gave a jaw-droppingly accurate description of German drummers ofJabula came into their own on the finale of the nineteen- rock ofthe late 60s and early 70s. For openers he stated that in the UK there was minute 'Part One' would be heard again on Oldfield's 1978 doublc a total ofcontinental rock. Secondly, there was a strong album Incarltatiol1S. 1984 Oldfield was great folk-rock songs with spirit among Germany's youth since 1968. They disliked rich P\fwl,()-I'\ 111 er1elln Reilly such as 'To France' and that year he also scored Roland groups playing in their country and a lot of students demanded free entry. The film The Killing Fields. Yet his first success would not go away concept of 'the revolutionary head' was paramount, a concept which 'chal and in 1992 Warner Bros. -

Rationalizing Culture : IRCAM, Boulez, and the Institutionalization of the Musical Avant-Garde / Georgina Born, P

IRCAM, Boulez, and the Institutionalization of the CULTUR Musical Avant-Garde GEORGINA RATIONALIZING BORN Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2019 with funding from Kahle/Austin Foundation https://archive.org/details/rationalizingculOOOOborn Rationalizing Culture Rationalizing Culture IRC AM, Boulez, and the Institutionalization of the Musical Avant-Garde w II Georgina Born UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PRESS Berkeley • Los Angeles • London This book is a print-on-demand volume. It is manufactured using toner in place of ink. Type and images may be less sharp than the same material seen in traditionally printed University of California Press editions. University of California Press Berkeley and Los Angeles, California University of California Press, Ltd. London, England © 1995 by The Regents of the University of California Born, Georgina, 1955 — Rationalizing culture : IRCAM, Boulez, and the Institutionalization of the Musical Avant-Garde / Georgina Born, p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-510-08507-8 (alk. paper) IRCAM (Research institute : France) 2. Avant- garde (Music) —Social aspects. 3. Research institutes —France— Anthropological aspects. 4. Boulez, Pierre, 1925-Influence. I. Title. ML32.F82I745 1994 3o6.4'84 — ddo 93-39386 CIP MN Printed in the United States of America The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences — Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1984. © For my parents, Andrew, and Irma Modern art as an art of tyrannizing —A coarse and strongly defined logic of delineation; motifs simplified to the point of formulas; the formula tyrannizes. Within the delineations a wild multiplicity, an overwhelming mass, before which the senses become confused; brutality in color, material, desires. -

Hybridity, Or the Cultural Logic of Globalization

P1: OTE TUPB007-Kraidy May 5, 2005 0:9 Hybridity, or the Cultural Logic of Globalization i Hybridity, or the Cultural Logic of Globalization Hybridity, or the Cultural Logic of Globalization MARWAN M. KRAIDY TEMPLE UNIVERSITY PRESS Philadelphia Marwan M. Kraidy is Assistant Professor of International Communication at the School of International Service, American University. He is co-editor of Global Media Studies: Ethnographic Perspectives. Temple University Press 1601 North Broad Street Philadelphia PA 19122 www.temple.edu/tempress Copyright C 2005 by Temple University All rights reserved Published 2005 Printed in the United States of America ∞ The paper used in this publication meets the requirements of the American National Standard for Information Sciences—Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1992 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Kraidy, Marwan, 1972– Hybridity, or the cultural logic of globalization / Marwan M. Kraidy. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 1-59213-143-3 (cloth : alk. paper) – ISBN 1-59213-144-1 (pbk : alk. paper) 1. Hybridity (Social sciences). 2. Hybridity (Social sciences)—Case studies. I. Title. HM1272.K73 2005 306—dc22 2004062108 246897531 Contents Preface vi Acknowledgments xiii 1 Cultural Hybridity and International Communication 1 2 Scenarios of Global Culture 15 3 The Trails and Tales of Hybridity 45 4 Corporate Transculturalism 72 5 The Cultural and Political Economies of Hybrid Media Texts 97 6 Structure, Reception, and Identity: On Arab-Western Dialogism 116 7 Hybridity without Guarantees: Toward Critical Transculturalism 148 Notes 163 Bibliography 177 Index 211 Preface Hybridity is almost a good idea, but not quite. -

ST/LIFE/PAGE<LIF-004>

D4 life happenings | THE STRAITS TIMES | FRIDAY, MAY 11, 2018 | GIGS Valentina Lisitsa Live In Singapore Aureus Productions’ third instalment Picks of the Aureus Great Artists Series features Ukrainian-American pianist Valentina Lisitsa, whose YouTube Gigs channel has more than 160 million views and some 400,000 subscribers. She made her New York debut at the Mostly Mozart Festival at Lincoln Centre in 1995 and has performed at venues such as Carnegie Hall, Vienna’s Musikverein and the Royal Albert Hall in London. WHERE: Esplanade Concert Hall, 1 Esplanade Drive MRT: Esplanade/ City Hall WHEN: May 20, 7.30pm ADMISSION: $48 - $88 TEL: 6348-5555 INFO: www.sistic.com.sg Jo Koy Break The Mold Tour Filipino-American comedian Jo Koy has come a long way from his modest beginnings performing at a Las Vegas coffee house. As one of today’s premiere stand-up comedians, he sells out comedy clubs and theatres across the United States. WHERE: Zepp@BigBox Singapore, 1 Venture Avenue MRT: Jurong East Eddino Abdul Hadi SIFA 2018 | SKY KAVE music and sounds. Titled Sky Kave, it WHERE: Play Den, Festival House, WHEN: June 30, 7pm ADMISSION: $88 Singer, songwriter and composer includes new works by a collaboration 1 Old Parliament Lane - $168 TEL: 6348-5555 Music Correspondent Ferry (above), together with technical between producer and composer MRT: Raffles Place/City Hall/ INFO: www.sistic.com.sg recommends collaborators Rong Zhao and Kelvin Evanturetime and deaf artist and Clarke Quay WHEN: Until tomorrow, Celine Dion Live In Singapore Ang, has created a music and visual photographer Issy.