Shackleton's Geologist

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Navigation on Shackleton's Voyage to Antarctica

Records of the Canterbury Museum, 2019 Vol. 33: 5–22 © Canterbury Museum 2019 5 Navigation on Shackleton’s voyage to Antarctica Lars Bergman1 and Robin G Stuart2 1Saltsjöbaden, Sweden 2Valhalla, New York, USA Email: [email protected] On 19 January 1915, the Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition, under the leadership of Sir Ernest Shackleton, became trapped in their vessel Endurance in the ice pack of the Weddell Sea. The subsequent ordeal and efforts that lead to the successful rescue of all expedition members are the stuff of legend and have been extensively discussed elsewhere. Prior to that time, however, the voyage had proceeded relatively uneventfully and was dutifully recorded in Captain Frank Worsley’s log and work book. This provides a window into the navigational methods used in the day-to- day running of the ship by a master mariner under normal circumstances in the early twentieth century. The conclusions that can be gleaned from a careful inspection of the log book over this period are described here. Keywords: celestial navigation, dead reckoning, double altitudes, Ernest Shackleton, Frank Worsley, Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition, Mercator sailing, time sight Introduction On 8 August 1914, the Imperial Trans-Antarctic passage in the 22½ foot (6.9 m) James Caird to Expedition under the leadership of Sir Ernest seek rescue from South Georgia. It is ultimately Shackleton set sail aboard their vessel the steam a tribute to Shackleton’s leadership and Worsley’s yacht (S.Y.) Endurance from Plymouth, England, navigational skills that all survived their ordeal. with the goal of traversing the Antarctic Captain Frank Worsley’s original log books continent from the Weddell to Ross Seas. -

Antarctic Peninsula

Hucke-Gaete, R, Torres, D. & Vallejos, V. 1997c. Entanglement of Antarctic fur seals, Arctocephalus gazella, by marine debris at Cape Shirreff and San Telmo Islets, Livingston Island, Antarctica: 1998-1997. Serie Científica Instituto Antártico Chileno 47: 123-135. Hucke-Gaete, R., Osman, L.P., Moreno, C.A. & Torres, D. 2004. Examining natural population growth from near extinction: the case of the Antarctic fur seal at the South Shetlands, Antarctica. Polar Biology 27 (5): 304–311 Huckstadt, L., Costa, D. P., McDonald, B. I., Tremblay, Y., Crocker, D. E., Goebel, M. E. & Fedak, M. E. 2006. Habitat Selection and Foraging Behavior of Southern Elephant Seals in the Western Antarctic Peninsula. American Geophysical Union, Fall Meeting 2006, abstract #OS33A-1684. INACH (Instituto Antártico Chileno) 2010. Chilean Antarctic Program of Scientific Research 2009-2010. Chilean Antarctic Institute Research Projects Department. Santiago, Chile. Kawaguchi, S., Nicol, S., Taki, K. & Naganobu, M. 2006. Fishing ground selection in the Antarctic krill fishery: Trends in patterns across years, seasons and nations. CCAMLR Science, 13: 117–141. Krause, D. J., Goebel, M. E., Marshall, G. J., & Abernathy, K. (2015). Novel foraging strategies observed in a growing leopard seal (Hydrurga leptonyx) population at Livingston Island, Antarctic Peninsula. Animal Biotelemetry, 3:24. Krause, D.J., Goebel, M.E., Marshall. G.J. & Abernathy, K. In Press. Summer diving and haul-out behavior of leopard seals (Hydrurga leptonyx) near mesopredator breeding colonies at Livingston Island, Antarctic Peninsula. Marine Mammal Science.Leppe, M., Fernandoy, F., Palma-Heldt, S. & Moisan, P 2004. Flora mesozoica en los depósitos morrénicos de cabo Shirreff, isla Livingston, Shetland del Sur, Península Antártica, in Actas del 10º Congreso Geológico Chileno. -

2. Disc Resources

An early map of the world Resource D1 A map of the world drawn in 1570 shows ‘Terra Australis Nondum Cognita’ (the unknown south land). National Library of Australia Expeditions to Antarctica 1770 –1830 and 1910 –1913 Resource D2 Voyages to Antarctica 1770–1830 1772–75 1819–20 1820–21 Cook (Britain) Bransfield (Britain) Palmer (United States) ▼ ▼ ▼ ▼ ▼ Resolution and Adventure Williams Hero 1819 1819–21 1820–21 Smith (Britain) ▼ Bellingshausen (Russia) Davis (United States) ▼ ▼ ▼ Williams Vostok and Mirnyi Cecilia 1822–24 Weddell (Britain) ▼ Jane and Beaufoy 1830–32 Biscoe (Britain) ★ ▼ Tula and Lively South Pole expeditions 1910–13 1910–12 1910–13 Amundsen (Norway) Scott (Britain) sledge ▼ ▼ ship ▼ Source: Both maps American Geographical Society Source: Major voyages to Antarctica during the 19th century Resource D3 Voyage leader Date Nationality Ships Most southerly Achievements latitude reached Bellingshausen 1819–21 Russian Vostok and Mirnyi 69˚53’S Circumnavigated Antarctica. Discovered Peter Iøy and Alexander Island. Charted the coast round South Georgia, the South Shetland Islands and the South Sandwich Islands. Made the earliest sighting of the Antarctic continent. Dumont d’Urville 1837–40 French Astrolabe and Zeelée 66°S Discovered Terre Adélie in 1840. The expedition made extensive natural history collections. Wilkes 1838–42 United States Vincennes and Followed the edge of the East Antarctic pack ice for 2400 km, 6 other vessels confirming the existence of the Antarctic continent. Ross 1839–43 British Erebus and Terror 78°17’S Discovered the Transantarctic Mountains, Ross Ice Shelf, Ross Island and the volcanoes Erebus and Terror. The expedition made comprehensive magnetic measurements and natural history collections. -

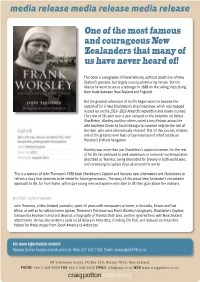

One of the Most Famous and Courageous New Zealanders That Many of Us Have Never Heard Of!

One of the most famous and courageous New Zealanders that many of us have never heard of! This book is a biography of Frank Worsley, without doubt one of New Zealand’s greatest, but largely unsung adventuring heroes. Born in Akaroa he went to sea as a teenager in 1888 on the sailing ships plying their trade between New Zealand and England. But the greatest adventure of his life began when he became the captain of Sir Ernest Shackleton’s ship Endurance, which was trapped in pack ice on the 1914–1916 Antarctic expedition and slowly crushed. The crew of 28 spent over a year camped on the Antarctic ice before Shackleton, Worsley and four others sailed a tiny lifeboat across the wild Southern Ocean to South Georgia to summon help for the rest of the men, who were all eventually rescued. This 17-day journey remains one of the greatest ever feats of seamanship and relied totally on Worsley’s brilliant navigation. Worsley was more than just Shackleton’s captain however. For the rest of his life he continued to seek adventures in a manner contemporaries described as ‘fearless’, being decorated for bravery in both world wars, and continuing to captain ships all around the world. This is a revision of John Thomson’s 1998 book Shackleton’s Captain and features new information and illustrations to refresh a story that deserves to be retold for future generations. The story of this proud New Zealander’s remarkable approach to life, far from home, will inspire young men and women who dare to lift their gaze above the ordinary. -

Antarctic Primer

Antarctic Primer By Nigel Sitwell, Tom Ritchie & Gary Miller By Nigel Sitwell, Tom Ritchie & Gary Miller Designed by: Olivia Young, Aurora Expeditions October 2018 Cover image © I.Tortosa Morgan Suite 12, Level 2 35 Buckingham Street Surry Hills, Sydney NSW 2010, Australia To anyone who goes to the Antarctic, there is a tremendous appeal, an unparalleled combination of grandeur, beauty, vastness, loneliness, and malevolence —all of which sound terribly melodramatic — but which truly convey the actual feeling of Antarctica. Where else in the world are all of these descriptions really true? —Captain T.L.M. Sunter, ‘The Antarctic Century Newsletter ANTARCTIC PRIMER 2018 | 3 CONTENTS I. CONSERVING ANTARCTICA Guidance for Visitors to the Antarctic Antarctica’s Historic Heritage South Georgia Biosecurity II. THE PHYSICAL ENVIRONMENT Antarctica The Southern Ocean The Continent Climate Atmospheric Phenomena The Ozone Hole Climate Change Sea Ice The Antarctic Ice Cap Icebergs A Short Glossary of Ice Terms III. THE BIOLOGICAL ENVIRONMENT Life in Antarctica Adapting to the Cold The Kingdom of Krill IV. THE WILDLIFE Antarctic Squids Antarctic Fishes Antarctic Birds Antarctic Seals Antarctic Whales 4 AURORA EXPEDITIONS | Pioneering expedition travel to the heart of nature. CONTENTS V. EXPLORERS AND SCIENTISTS The Exploration of Antarctica The Antarctic Treaty VI. PLACES YOU MAY VISIT South Shetland Islands Antarctic Peninsula Weddell Sea South Orkney Islands South Georgia The Falkland Islands South Sandwich Islands The Historic Ross Sea Sector Commonwealth Bay VII. FURTHER READING VIII. WILDLIFE CHECKLISTS ANTARCTIC PRIMER 2018 | 5 Adélie penguins in the Antarctic Peninsula I. CONSERVING ANTARCTICA Antarctica is the largest wilderness area on earth, a place that must be preserved in its present, virtually pristine state. -

THE PUBLICATION of the NEW ZEALAND ANTARCTIC SOCIETY Vol 34, No

THE PUBLICATION OF THE NEW ZEALAND ANTARCTIC SOCIETY Vol 34, No. 3, 2016 34, No. Vol 03 9 770003 532006 Vol 34, No. 3, 2016 Issue 237 Contents www.antarctic.org.nz is published quarterly by the New Zealand Antarctic Society Inc. ISSN 0003-5327 30 The New Zealand Antarctic Society is a Registered Charity CC27118 EDITOR: Lester Chaplow ASSISTANT EDITOR: Janet Bray New Zealand Antarctic Society PO Box 404, Christchurch 8140, New Zealand Email: [email protected] INDEXER: Mike Wing The deadlines for submissions to future issues are 1 November, 1 February, 1 May and 1 August. News 25 Shackleton’s Bad Lads 26 PATRON OF THE NEW ZEALAND ANTARCTIC SOCIETY: From Gateway City to Volunteer Duty at Scott Base 30 Professor Peter Barrett, 2008 NEW ZEALAND ANTARCTIC SOCIETY How You Can Help Us Save Sir Ed’s Antarctic Legacy 33 LIFE MEMBERS The Society recognises with life membership, First at Arrival Heights 34 those people who excel in furthering the aims and objectives of the Society or who have given outstanding service in Antarctica. They are Conservation Trophy 2016 36 elected by vote at the Annual General Meeting. The number of life members can be no more Auckland Branch Midwinter Celebration 37 than 15 at any one time. Current Life Members by the year elected: Wellington Branch – 2016 Midwinter Event 37 1. Jim Lowery (Wellington), 1982 2. Robin Ormerod (Wellington), 1996 3. Baden Norris (Canterbury), 2003 Travelling with the Huskies Through 4. Bill Cranfield (Canterbury), 2003 the Transantarctic Mountains 38 5. Randal Heke (Wellington), 2003 6. Bill Hopper (Wellington), 2004 Hillary’s TAE/IGY Hut: Calling all stories 40 7. -

Scott Polar Research Institute 100 Years Charlotte Connelly Tells Us About the History of SPRI

landmark Summer 2020 I Edition 8 Scott Polar Research Institute 100 years Charlotte Connelly tells us about the history of SPRI Geographies of Health Alice Reid on geographies of health and demography The Department of Geography alumni magazine ©Sir Cam Inside Scott Polar Research Institute 100 years 4 Geographies of Health 6 Alumni views 8 A more diverse future for Geography 9 Conservation Leadership 10 Managing disasters 12 Welcome to the 2020 edition of landmark e always expected 2020 to delivered remotely during the Easter Term, and be a memorable year at the undergraduate examinations moved online. It is Department, but perhaps not for testimony to the extraordinary commitment of W the reasons that have dominated colleagues that we were able to manage all these the last few months, during which coping with changes reasonably well, while still delivering Covid-19 has overshadowed all our activities. In this the best possible experiences for students, and edition of Landmark, we celebrate the centenary of being mindful of the wellbeing and health of all the founding of the Scott Polar Research Institute concerned. I am very fortunate to be surrounded and a decade since the launch of the flagship by people who care, and who have worked MPhil programme in Conservation Leadership. tirelessly to support the Department through this We look forward to welcoming the first cohorts of period. students for our two new Masters programmes in Anthropocene Studies and Holocene Climates with We have seen other creative ways to adapt to the a feature on our colleague, Amy Donovan, who new challenges that we all face. -

The Centenary of the Scott Expedition to Antarctica and of the United Kingdom’S Enduring Scientific Legacy and Ongoing Presence There”

Debate on 18 October: Scott Expedition to Antarctica and Scientific Legacy This Library Note provides background reading for the debate to be held on Thursday, 18 October: “the centenary of the Scott Expedition to Antarctica and of the United Kingdom’s enduring scientific legacy and ongoing presence there” The Note provides information on Antarctica’s geography and environment; provides a history of its exploration; outlines the international agreements that govern the territory; and summarises international scientific cooperation and the UK’s continuing role and presence. Ian Cruse 15 October 2012 LLN 2012/034 House of Lords Library Notes are compiled for the benefit of Members of the House of Lords and their personal staff, to provide impartial, politically balanced briefing on subjects likely to be of interest to Members of the Lords. Authors are available to discuss the contents of the Notes with the Members and their staff but cannot advise members of the general public. Any comments on Library Notes should be sent to the Head of Research Services, House of Lords Library, London SW1A 0PW or emailed to [email protected]. Table of Contents 1.1 Geophysics of Antarctica ....................................................................................... 1 1.2 Environmental Concerns about the Antarctic ......................................................... 2 2.1 Britain’s Early Interest in the Antarctic .................................................................... 4 2.2 Heroic Age of Antarctic Exploration ....................................................................... -

In Shackleton's Footsteps

In Shackleton’s Footsteps 20 March – 06 April 2019 | Polar Pioneer About Us Aurora Expeditions embodies the spirit of adventure, travelling to some of the most wild and adventure and discovery. Our highly experienced expedition team of naturalists, historians and remote places on our planet. With over 27 years’ experience, our small group voyages allow for destination specialists are passionate and knowledgeable – they are the secret to a fulfilling a truly intimate experience with nature. and successful voyage. Our expeditions push the boundaries with flexible and innovative itineraries, exciting wildlife Whilst we are dedicated to providing a ‘trip of a lifetime’, we are also deeply committed to experiences and fascinating lectures. You’ll share your adventure with a group of like-minded education and preservation of the environment. Our aim is to travel respectfully, creating souls in a relaxed, casual atmosphere while making the most of every opportunity for lifelong ambassadors for the protection of our destinations. DAY 1 | Wednesday 20 March 2019 Ushuaia, Beagle Channel Position: 21:50 hours Course: 84° Wind Speed: 5 knots Barometer: 1007.9 hPa & falling Latitude: 54°55’ S Speed: 9.4 knots Wind Direction: E Air Temp: 11°C Longitude: 67°26’ W Sea Temp: 9°C Finally, we were here, in Ushuaia aboard a sturdy ice-strengthened vessel. At the wharf Gary Our Argentinian pilot climbed aboard and at 1900 we cast off lines and eased away from the and Robyn ticked off names, nabbed our passports and sent us off to Kathrine and Scott for a wharf. What a feeling! The thriving city of Ushuaia receded as we motored eastward down the quick photo before boarding Polar Pioneer. -

On 8 August 1914, Ernest Shackleton and His Brave Crew Set out to Cross the Vast South Polar Continent, Antarctica

Born on 15 February 1874, Shackleton was the second of ten children. From a young age, Shackleton complained about teachers, but he had a keen interest in books, especially poetry – years later, on expeditions, he would read to his crew to lift their spirits. Always restless, the young Ernest left school at 16 to go to sea. After working his way up the ranks, he told his friends, “I think I can do something better, I want to make a name for myself.” Shackleton was a member of Captain Scott’s famous Discovery expedition (1901-1904), and told reporters that he had always been “strangely drawn to the mysterious south” and that unexplored parts of the world “held a strong fascination for me from my earliest memories”. Once Amundsen reached the South Pole ahead of Scott, Shackleton realised that there was only one great challenge left. He wrote: “The first crossing of the Antarctic continent, from sea to sea, via the Pole, apart from its historic value, will be a journey of great scientific importance.” On 8 August 1914, Ernest Shackleton and his brave crew set out to cross the vast south polar continent, Antarctica. Shackleton’s epic journey would be the last expedition of the Heroic Age of Antarctic Exploration (1888-1914). His story is one fraught with unimaginable peril, adventure and, above all, endurance. 1 2 JAMES WORDIE TIMOTHY McCARTHY ALFRED CHEETHAM Expedition geologist. Able seaman. Third officer. FRANK WORSLEY ERNEST SHACKLETON FRANK WILD FRANK HURLEY DR. JAMES McILROY DR. ALEXANDER MACKLIN Ship’s captain. Expedition leader. Second-in-command. -

THE DEVELOPMENT of LANDFORM STUDIES in AUSTRALIA by H.I

THE DEVELOPMENT OF LANDFORM STUDIES IN AUSTRALIA by H.I. Scott, B.A.Qld.,M.Sc.Macq. Submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Geography, August 1976 University of New South Wales UNIVERSITY OF N.S.W., 27922 T3.DEC.77 LIBRARY ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Directly and indirectly, I am indebted to many people. Many of those whose writing has stimulated me are mentioned in the Bibliography, but I wish to thank the following in particular: My Supervisor, Professor J.A. Mabbutt, Head, School of Geography, University of New South Wales, for his helpful criticisms, suggestions and financial assis tance by way of my appointment as part-time tutor in the Department; Dr. G. Seddon, Director, Centre for Environmental Studies, University of Melbourne, previously Professor and Head of the School of The History and Philosophy of Science, University of New South Wales, and my Co-Supervisor during Professor Mabbutt's Sabbatical Leave, for his helpful cri ticisms of the early drafts of the various Chapters; Professor J.N. Jennings, Professorial Fellow, Department of Biogeography and Geomorphology; Research School of Pacific Studies, Australian National University, Canberra, for his helpful comments on the last five Chapters, his discussion concerning the development of Australian geomorphology since 1945 , and related matters by way of Correspondence. \ Emeritus Professor E.S. Hills, Department of Geology, University of Melbourne, for his helpful comments on Chapters Eight, Nine, and Eleven, and for his time in dis cussing the role which he and his Department played in the development of geomorphology in Victoria during the pre- and post-war periods; Dr. -

The Scott Polar Research Institute Was Established

THESCOTT POLAR RESEARCH INSTITUTE G. C. L. Bertram* UST forty years have passed since Captain Robert Falcon Scott and his four J companions died while returning from the South Pole. The journey and end of these men is a story which has probably stirred Britons more than any other peacetime event in centuries. They rallied nobly to Scott’s last appeal to “see that those who are dependent on us are properly provided for”, and theCaptain Scott Memorial Mansion HouseFund soon reached a total of A;76,500 for disposal by its trustees. When the Mansion House Fund had fulfilled its dual task of providing for dependents and of publishing the scientific reports, there still remained a sum of 13,000 set aside as a “PolarResearch Fund’’. It was at thistime, in the early ’twenties, that Frank Debenham, later Professor of Geography in the University of Cambridge, put forward proposals which sprang from discussions towards the end of 1912 with two other members of the Antarctic Expedition: Raymond Priestley, until recently Vice-Chancellor of Birmingham University, and Charles Wright, who later became Chief of the Royal Naval Scientific Service. Debenham showed convincingly that often the hard-won experience of polar expeditions in the past had been lost when their members dispersed, and that the techniques of life and travel in cold regions had been inadequately ‘Director, Scott Polar Research Institute, Cambridge, England. 153 154 THERESEARCHPOLAR SCOTT INSTITUTE recorded.Each expedition had had to learn these techniquesanew, rarely profiting from the experience of others,and in this way valuable time and even lives had been lost.