Excerpted From

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Eastmont High School Items

TO: Board of Directors FROM: Garn Christensen, Superintendent SUBJECT: Requests for Surplus DATE: June 7, 2021 CATEGORY ☐Informational ☐Discussion Only ☐Discussion & Action ☒Action BACKGROUND INFORMATION AND ADMINISTRATIVE CONSIDERATION Staff from the following buildings have curriculum, furniture, or equipment lists and the Executive Directors have reviewed and approved this as surplus: 1. Cascade Elementary items. 2. Grant Elementary items. 3. Kenroy Elementary items. 4. Lee Elementary items. 5. Rock Island Elementary items. 6. Clovis Point Intermediate School items. 7. Sterling Intermediate School items. 8. Eastmont Junior High School items. 9. Eastmont High School items. 10. Eastmont District Office items. Grant Elementary School Library, Kenroy Elementary School Library, and Lee Elementary School Library staff request the attached lists of library books be declared as surplus. These lists will be posted separately on the website. Sterling Intermediate School Library staff request the attached list of old social studies textbooks be declared as surplus. These lists will be posted separately on the website. Eastmont Junior High School Library staff request the attached lists of library books and textbooks for both EJHS and Clovis Point Intermediate School be declared as surplus. These lists will be posted separately on the website. Eastmont High School Library staff request the attached lists of library books for both EHS and elementary schools be declared as surplus. These lists will be posted separately on the website. ATTACHMENTS FISCAL IMPACT ☒None ☒Revenue, if sold RECOMMENDATION The administration recommends the Board authorize said property as surplus. Eastmont Junior High School Eastmont School District #206 905 8th St. NE • East Wenatchee, WA 98802 • Telephone (509)884-6665 Amy Dorey, Principal Bob Celebrezze, Assistant Principal Holly Cornehl, Asst. -

2012 NHBB Set C Round #2

2012 NHBB Set C Bowl Round 2 First Quarter BOWL ROUND 2 1. This country was granted independence by the 1960 Zurich and London Agreement. Dimitrios Ioannides overthrew its president, Archbishop Makarios III, in 1974, resulting in a Turkish invasion to keep this island from reuniting with Greece. For 10 points, name this still-divided country in the eastern Mediterranean. ANSWER: Republic of Cyprus 003-12-64-02101 2. Dwight Eisenhower accused one leader of this organization of leaving a “legacy of ashes.” It was investigated in the Senate by the Church Committee after a Seymour Hirsch article about its “family jewels.” It was established by the National Security Act in 1947. Under Allen Dulles, it participated in the overthrow of Mohammad Mosaddegh in Iran. For 10 points, name this civilian intelligence agency. ANSWER: Central Intelligence Agency [or CIA] 121-12-64-02102 3. This leader released many of his country's criminals from prison and shipped them off to America in the Mariel Boatlift. An American plan to assassinate this man with an exploding cigar failed. In 1959, this man overthrew Fulgencio Batista with the help of Che Guevara and his brother Raul. For 10 points, name this longtime Communist dictator of Cuba. ANSWER: Fidel Castro 080-12-64-02103 4. This man composed an operetta in which the Viceroy of Peru poses as rebel leader El Capitan. In 1889, he was commissioned to compose a piece for an awards ceremony for The Washington Post. This man composed “Semper Fidelis,” which became the official march of the United States Marine Corps. -

2019 National History Bowl Middle School

Middle School National Bowl 2018-2019 Round 1 Round 1 First Quarter (1) During this battle, fierce fighting took place at the Chateau Hougoumont and La Haye Sainte. Prussian forces under Gebhard von Blucher reinforced British forces during this battle. In the aftermath of this battle one general was exiled to St. Helena having earlier escaped from Elba. The Duke of Wellington defeated the French at, for ten points, what 1815 battle, the final defeat of Napoleon? ANSWER: Battle of Waterloo (2) This man was named Sheltowee after he was captured during a fight with Chief Blackfish, though he returned to being a Fayette County militia colonel in 1778. This man founded a namesake town in Kentucky after blazing the Wilderness Road through the Cumberland Gap. For ten points, name this explorer and frontiersman who became known as a folk hero with a coonskin cap. ANSWER: Colonel Daniel Boone (3) Phidias sculpted this deity as Promachos for a statue that held Nike in its right hand. In another sculpture, this deity holds an owl, and a statue of this goddess as Parthenos that stood in the Acropolis showed her with the Aegis, a shield decorated with the head of Medusa. Pallas is an epithet of, for ten points, what Greek goddess of war and wisdom? ANSWER: Athena (accept Athena Promachos; accept Athena Parthenos; accept Pallas Athena; do not accept or prompt on Minerva) (4) This action occurred to a double portrait by Rembrandt that was housed in Boston in 1990. This action was undertaken by two men posing as police officers, resulting in the loss of Vermeer's The Concert. -

Spreading the Light of Hanukkah Amidst This

As a teenager, I loved classic science-fiction television shows like Star Trek and The Twilight Zone . I remember countless late nights glued to the TV, listening to Rod Serling open the show: “ It is a dimension as vast as space and as timeless as infinity. It is the middle ground between light and shadow, between science and superstition, and it lies between the pit of man's fears and the summit of his knowledge. This is the dimension of imagination. It is an area which we call the T wilight Zone .” Its episodes were clever and engaging. Imagine a world, where the beauty standards were reversed and what we think of as ugly and disfigured is the normative standard and someone whom we think of as gorgeous is deemed horrific. Or the classic episode the Odyssey of Flight 33 where a plane somehow gets sucked into a time vortex and instead of being in the year 1961 when they took off, it is 1940 and there is no runway long enough to land on, no way to get back to the future…. (You could see where later 80s movie writers, like Robert Zemeckis and Bob Gale , found their inspiration!) This was a show that pushed the limits of our imagination and like all great literature allowed for the “willing suspension of disbelief,” as Aristotle first explained it. This allows for the audience watching a play (or reading a novel or seeing a show or a movie) to enter into a space where we can leave reality behind, and enjoy the stimulation of the art. -

Cigar Aficionado Miami Herald

U.S.-Cuba Trade and Economic Council, Inc. New York, New York Telephone (917) 453-6726 • E-mail: [email protected] Internet: http://www.cubatrade.org • Twitter: @CubaCouncil Facebook: www.facebook.com/uscubatradeandeconomiccouncil LinkedIn: www.linkedin.com/company/u-s--cuba-trade-and-economic-council-inc- Cigar Aficionado New York, New York 21 October 2016 Havana’s Sheraton Four Points To Accept MasterCard, But There’s A Catch By Gordon Mott Starwood Hotels has announced that the Sheraton Four Points hotel in Havana, Cuba will begin accepting U.S.-issued MasterCards for payment of guest rooms, according to a report by the U.S.–Cuba Trade and Economic Council. (Starwood took over operations of the hotel in late June.) The change puts the hotel in agreement with regulations that went into effect in January 2015. There’s a major catch, however. To date, the Office of Foreign Assets Control and Cuba’s Central Bank have only authorized MasterCards issued by three banks to make charges in Cuba: Stonegate, Natbank (both based in Florida) and Banco Popular de Puerto Rico. For Americans who do not have a MasterCard issued by one of those banks, or a foreign bank-issued credit card, you must pay all your expenses with cash. Therefore, cards from the three largest U.S banks that issue MasterCard and Visa—JPMorgan Chase & Co., Citibank and Bank of America—will not work in Cuba. American Express, the largest credit card issuer in the United States, has said it is working on having its cards accepted in Cuba, but to date, nothing has come of those efforts. -

The Poetry Lady of Del

Alexandria Times Vol. 15, No. 14 Alexandria’s only independent hometown newspaper. APRIL 4, 2019 The poetry lady of Del Ray The giving Renée season Renée Adams celebrates 10 Adams years of her poetry fence began Alexandria businesses put pinning the “community” in “busi- BY MISSY SCHROTT poetry, ness community” pictures, To know Renée Adams is to know comics BY CODY MELLO-KLEIN her love of poetry, and in Del Ray, and her name is inextricably linked with quotes Thousands of residents donate on the mention of her poetry fence. to local nonprofits both during fence This month, Adams is celebrating border- ACT for Alexandria’s Spring2AC- the 10-year anniversary of the land- ing her Tion – for which early giving is mark poetry fence. But in the past yard in already underway leading up to decade, she’s done more than pro- 2009. the April 10 day of giving – and vide neighbors and passersby with a PHOTO/ throughout the year. MISSY But philanthropy in Alexan- SEE POETRY | 12 SCHROTT dria is not limited to individuals and families; many of the city’s businesses are integrated into Al- exandria’s fabric and give back to Murder case Mirror, Mirror the community in ways both big and small. Alexandria’s thriving, hyper- mistrial local community of restaurants, Defendant thought victim was werewolf SEE GIVING | 16 BY CODY MELLO-KLEIN INSIDE An Alexandria judge de- Parks clared a mistrial on March 27 in Angel Park has lengthy past, the murder case of a man who soggy present. claimed he thought his victim Page 6 was a werewolf, according to Commonwealth’s Attorney Bryan Business Porter. -

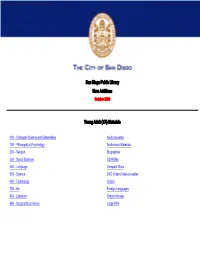

San Diego Public Library New Additions October 2009

San Diego Public Library New Additions October 2009 Young Adult (YA) Materials 000 - Computer Science and Generalities Audiocassettes 100 - Philosophy & Psychology Audiovisual Materials 200 - Religion Biographies 300 - Social Sciences CD-ROMs 400 - Language Compact Discs 500 - Science DVD Videos/Videocassettes 600 - Technology Fiction 700 - Art Foreign Languages 800 - Literature Graphic Novels 900 - Geography & History Large Print Fiction Call # Author Title YA FIC/ALEXANDER Alexander, Alma. Spellspam YA FIC/BARNHOLDT Barnholdt, Lauren. Reality chick YA FIC/BASKIN Baskin, Nora Raleigh. Anything but typical YA FIC/BERRY Berry, Julie, 1974- The Amaranth enchantment YA FIC/BLOOR Bloor, Edward, 1950- Taken YA FIC/BRASHARES Brashares, Ann. 3 willows : the sisterhood grows YA FIC/BRIAN Brian, Kate, 1974- Confessions : a novel YA FIC/BRIAN Brian, Kate, 1974- Inner circle : a novel YA FIC/BRIAN Brian, Kate, 1974- Invitation only : a novel YA FIC/BRIAN Brian, Kate, 1974- Legacy : novel YA FIC/BRIAN Brian, Kate, 1974- Private : a novel YA FIC/BRIAN Brian, Kate, 1974- Untouchable : a novel YA FIC/CALAME Calame, Don. Swim the fly YA FIC/CANTOR Cantor, Jillian. The September sisters YA FIC/CARDENAS Cárdenas Angulo, Teresa, 1970- Old dog YA FIC/CARMODY Carmody, Isobelle. Wavesong YA FIC/CARRILLO Carrillo, P. S. Desert passage YA FIC/CAST Cast, P. C. Hunted : a house of night novel YA FIC/CAST Cast, P. C. Marked YA FIC/CATANESE Catanese, P. W. Happenstance found YA FIC/CAVENEY Caveney, Philip. Sebastian Darke : Prince of Pirates YA FIC/COCKCROFT Cockcroft, Jason. CounterClockwise YA FIC/COLLARD Collard, Sneed B. Double eagle YA FIC/COLLINS Collins, Suzanne. Catching fire YA FIC/CONRAD Conrad, Lauren. -

Living in the Twilight Zone

NWAnews.com :: Northwest Arkansas' News Source 3/4/09 12:28 AM In the Zone BY RON WOLFE Posted on Saturday, February 28, 2009 URL: http://www.nwanews.com/adg/Style/253699/ You open this door with the key of imagination. But what if you've lost the key? Keys disappear, and even stranger things happen at home. Rod Serling knew. His classic TV series, The Twilight Zone, claimed to be set in the fifth dimension. But some of the creepiest episodes deal with things commonly found around the house: mirrors (that show something out of place), telephones (that speak for themselves), children's toys (that come to life). "I believe Serling himself thought of home as a haven," says Andrew Polak of the Rod Serling Memorial Foundation in Serling's hometown of Binghamton, N.Y. But in many of the stories that Serling and other writers imagined for The Twilight Zone, the house "was a convenient place for things to go wrong." Serling generally set his stories in the most ordinary circumstances. Home, especially, made the unexpected all the more, well - Twilight Zone-ish. "The strangeness of the known, rather than the unknown, can be very effective," Polak says. Viewers "could put themselves in the situation, driving the impact home." In "The Monsters Are Due on Maple Street," for example, good neighbors turn against each other when the electricity goes on and off at random. One house has lights, but the place next door doesn't. The power company might explain what happened: houses on different circuits, repair crews doing the best they can. -

Philosophy in the Twilight Zone

9781405149044_1_pre.qxd 10/2/09 10:49 AM Page iii Philosophy in The Twilight Zone edited by Noël Carroll and Lester H. Hunt A John Wiley & Sons, Ltd., Publication 9781405149044_1_pre.qxd 10/2/09 10:49 AM Page iv 9781405149044_1_pre.qxd 10/2/09 10:48 AM Page i Philosophy in The Twilight Zone 9781405149044_1_pre.qxd 10/2/09 10:48 AM Page ii 9781405149044_1_pre.qxd 10/2/09 10:48 AM Page iii Philosophy in The Twilight Zone edited by Noël Carroll and Lester H. Hunt A John Wiley & Sons, Ltd., Publication 9781405149044_1_pre.qxd 10/2/09 10:48 AM Page iv This edition first published 2009 © 2009 Blackwell Publishing Ltd Blackwell Publishing was acquired by John Wiley & Sons in February 2007. Blackwell’s publishing program has been merged with Wiley’s global Scientific, Technical, and Medical business to form Wiley-Blackwell. Registered Office John Wiley & Sons Ltd, The Atrium, Southern Gate, Chichester, West Sussex, PO19 8SQ, United Kingdom Editorial Offices 350 Main Street, Malden, MA 02148-5020, USA 9600 Garsington Road, Oxford, OX4 2DQ, UK The Atrium, Southern Gate, Chichester, West Sussex, PO19 8SQ, UK For details of our global editorial offices, for customer services, and for information about how to apply for permission to reuse the copyright material in this book please see our website at www.wiley.com/wiley-blackwell. The right of Noël Carroll and Lester Hunt to be identified as the authors of the editorial material in this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. -

The Twilight Zone: Complete Stories the Twilight Zone: Complete Stories

(Mobile book) The Twilight Zone: Complete Stories The Twilight Zone: Complete Stories Moxi2wexe The Twilight Zone: Complete Stories VfP26Oki5 YA-42753 ZY4x4WN0P US/Data/Literature-Fiction 1V0KVgmYy 3.5/5 From 626 Reviews xcCWlGYZY Rod Serling WfPQxnjSl DOC | *audiobook | ebooks | Download PDF | ePub ywKZh5F7S N8ZXh16fe mZ7hwFhmi hCZtqLb70 RikWgV4bZ TERRkfuhS 0qi1qXSy7 ZkDupmMEz 6 of 6 people found the following review helpful. For everyoneBy Anthony LWr6yRPYp IozzoThis is truly a great collection of stories. I am a fan of the Twilight Zone QgwFREwc0 and have read Richard Matheson, Charles Beaumont, Damon Knight and ObBtBRj1v others who have contributed to the series. This anthology is by far the best. I SBFBCo74P enjoyed Serling's clear and fluid style. Images of the episodes they were based IkQHJRTD3 on constantly entered my mind.However the stories themselves went beyong the 5VofD76gl television series and could very well stand on there own. Anyone not familiar nAImQXiVn with the series could enjoy this collection. An absolute must have for fans and IOHWGW4tK sci-fi/fantasy lovers.0 of 0 people found the following review helpful. Great wAlm6eBJx Book!By CustomerRod Serling never disappoints with his masterful story lzPwyZv1y telling.23 of 27 people found the following review helpful. Coming from a big zAMLUIBGI TZ fan, this is an EXCELLENT bookBy A CustomerIt's difficult to write a n8wDVwc0h review on the whole book, so I would like to cut it into pieces.~The Mighty pisllPRDB Casey- I must say that I hate baseball and baseball stories, but the way Rod kGCwOJi5m Serling brought the Mighty Casey together just made it an instant favorite. -

SHSU Video Archive Basic Inventory List Department of Library Science

SHSU Video Archive Basic Inventory List Department of Library Science A & E: The Songmakers Collection, Volume One – Hitmakers: The Teens Who Stole Pop Music. c2001. A & E: The Songmakers Collection, Volume One – Dionne Warwick: Don’t Make Me Over. c2001. A & E: The Songmakers Collection, Volume Two – Bobby Darin. c2001. A & E: The Songmakers Collection, Volume Two – [1] Leiber & Stoller; [2] Burt Bacharach. c2001. A & E Top 10. Show #109 – Fads, with commercial blacks. Broadcast 11/18/99. (Weller Grossman Productions) A & E, USA, Channel 13-Houston Segments. Sally Cruikshank cartoon, Jukeboxes, Popular Culture Collection – Jesse Jones Library Abbott & Costello In Hollywood. c1945. ABC News Nightline: John Lennon Murdered; Tuesday, December 9, 1980. (MPI Home Video) ABC News Nightline: Porn Rock; September 14, 1985. Interview with Frank Zappa and Donny Osmond. Abe Lincoln In Illinois. 1939. Raymond Massey, Gene Lockhart, Ruth Gordon. John Ford, director. (Nostalgia Merchant) The Abominable Dr. Phibes. 1971. Vincent Price, Joseph Cotton. Above The Rim. 1994. Duane Martin, Tupac Shakur, Leon. (New Line) Abraham Lincoln. 1930. Walter Huston, Una Merkel. D.W. Griffith, director. (KVC Entertaiment) Absolute Power. 1996. Clint Eastwood, Gene Hackman, Laura Linney. (Castle Rock Entertainment) The Abyss, Part 1 [Wide Screen Edition]. 1989. Ed Harris. (20th Century Fox) The Abyss, Part 2 [Wide Screen Edition]. 1989. Ed Harris. (20th Century Fox) The Abyss. 1989. (20th Century Fox) Includes: [1] documentary; [2] scripts. The Abyss. 1989. (20th Century Fox) Includes: scripts; special materials. The Abyss. 1989. (20th Century Fox) Includes: special features – I. The Abyss. 1989. (20th Century Fox) Includes: special features – II. Academy Award Winners: Animated Short Films. -

Uncivil Obedience Lowell Darling Follows the Law

Uncivil Obedience Lowell Darling Follows the Law Monica Steinberg My tax problem is my work. I have always considered bureaucracy one of contemporary society’s highest art forms; and being an artist I naturally turned to red tape for material.1 —Lowell Darling The Gubernatorial Campaign “Let me be your governor, Darling.”2 On Valentine’s Day, 1978, artist Lowell Darling (b. 1942), speaking from a podium in the sculpture garden of the Berkeley Art Museum (fig. 1), announced his intent to seek the Democratic Party’s nomination for governor of California, challenging then incumbent Governor Edmund Gerald “Jerry” Brown—a Democrat who entered office in 1975. Here, Darling presented his political platform, “The Inevitable Campaign Slogans & Promises.”3 He vowed to solve unem- ployment by hiring state residents “to be themselves for the state of California,” such that Governor Brown would be hired to be himself and continue to perform his guber- natorial duties; and since everyone would be employed “to be themselves” (i.e., “self-employed”), all expenses would be tax deductible.4 Darling even pledged to abolish taxation altogether by turning the state budget over to Reverend Ike, a promi- nent televangelist who preached the blessings of material prosperity and was credited with performing monetary miracles (taxes would be unnecessary if one could manifest money out of thin air). Pollution would be solved by converting parking meters into slot machines (paying motorists to park their cars instead of drive them) and by replac- ing internal combustion engine cars with psychic-powered vehicles. To ensure political transparency and lawful practices at the highest level, Darling promised to establish a Presidential Television Network (PTN).