Report from Interagency Post Drought Assessment in Papua New Guinea

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Promoting Skill Transfer for Human Capacity Development in Papua New Guinea the Role of Externally Financed Infrastructure Projects

PROMOTING SKILL TRANSFER FOR HUMAN CAPACITY DEVELOPMENT IN PAPUA NEW GUINEA THE ROLE OF EXTERNALLY FINANCED INFRASTRUCTURE PROJECTS ASIAN DEVELOPMENT BANK PROMOTING SKILL TRANSFER FOR HUMAN CAPACITY DEVELOPMENT IN PAPUA NEW GUINEA THE ROLE OF EXTERNALLY FINANCED INFRASTRUCTURE PROJECTS ASIAN DEVELOPMENT BANK Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 IGO license (CC BY 3.0 IGO) © 2017 Asian Development Bank 6 ADB Avenue, Mandaluyong City, 1550 Metro Manila, Philippines Tel +63 2 632 4444; Fax +63 2 636 2444 www.adb.org Some rights reserved. Published in 2017. Printed in the Philippines. ISBN 978-92-9257-807-7 (Print), 978-92-9257-808-4 (e-ISBN) Publication Stock No. TCS178751-2 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.22617/TCS178751-2 Cataloging-In-Publication Data Asian Development Bank. Promoting skill transfer for human capacity development in Papua New Guinea: The role of externally financed infrastructure projects. Mandaluyong City, Philippines: Asian Development Bank, 2017. 1. Skill transfer. 2. Human capacity development. 3. Papua New Guinea. 4. Infrastructure. I. Asian Development Bank. The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views and policies of the Asian Development Bank (ADB) or its Board of Governors or the governments they represent. ADB does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this publication and accepts no responsibility for any consequence of their use. The mention of specific companies or products of manufacturers does not imply that they are endorsed or recommended by ADB in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. By making any designation of or reference to a particular territory or geographic area, or by using the term “country” in this document, ADB does not intend to make any judgments as to the legal or other status of any territory or area. -

Papua New Guinea

PAPUA NEW GUINEA EMERGENCY PREPAREDNESS OPERATIONAL LOGISTICS CONTINGENCY PLAN PART 2 –EXISTING RESPONSE CAPACITY & OVERVIEW OF LOGISTICS SITUATION GLOBAL LOGISTICS CLUSTER – WFP FEBRUARY – MARCH 2011 1 | P a g e A. Summary A. SUMMARY 2 B. EXISTING RESPONSE CAPACITIES 4 C. LOGISTICS ACTORS 6 A. THE LOGISTICS COORDINATION GROUP 6 B. PAPUA NEW GUINEAN ACTORS 6 AT NATIONAL LEVEL 6 AT PROVINCIAL LEVEL 9 C. INTERNATIONAL COORDINATION BODIES 10 DMT 10 THE INTERNATIONAL DEVELOPMENT COUNCIL 10 D. OVERVIEW OF LOGISTICS INFRASTRUCTURE, SERVICES & STOCKS 11 A. LOGISTICS INFRASTRUCTURES OF PNG 11 PORTS 11 AIRPORTS 14 ROADS 15 WATERWAYS 17 STORAGE 18 MILLING CAPACITIES 19 B. LOGISTICS SERVICES OF PNG 20 GENERAL CONSIDERATIONS 20 FUEL SUPPLY 20 TRANSPORTERS 21 HEAVY HANDLING AND POWER EQUIPMENT 21 POWER SUPPLY 21 TELECOMS 22 LOCAL SUPPLIES MARKETS 22 C. CUSTOMS CLEARANCE 23 IMPORT CLEARANCE PROCEDURES 23 TAX EXEMPTION PROCESS 24 THE IMPORTING PROCESS FOR EXEMPTIONS 25 D. REGULATORY DEPARTMENTS 26 CASA 26 DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH 26 NATIONAL INFORMATION AND COMMUNICATIONS TECHNOLOGY AUTHORITY (NICTA) 27 2 | P a g e MARITIME AUTHORITIES 28 1. NATIONAL MARITIME SAFETY AUTHORITY 28 2. TECHNICAL DEPARTMENTS DEPENDING FROM THE NATIONAL PORT CORPORATION LTD 30 E. PNG GLOBAL LOGISTICS CONCEPT OF OPERATIONS 34 A. CHALLENGES AND SOLUTIONS PROPOSED 34 MAJOR PROBLEMS/BOTTLENECKS IDENTIFIED: 34 SOLUTIONS PROPOSED 34 B. EXISTING OPERATIONAL CORRIDORS IN PNG 35 MAIN ENTRY POINTS: 35 SECONDARY ENTRY POINTS: 35 EXISTING CORRIDORS: 36 LOGISTICS HUBS: 39 C. STORAGE: 41 CURRENT SITUATION: 41 PROPOSED LONG TERM SOLUTION 41 DURING EMERGENCIES 41 D. DELIVERIES: 41 3 | P a g e B. Existing response capacities Here under is an updated list of the main response capacities currently present in the country. -

Wanbel: Conflict, Reconciliation and Personhood Among the Sam People, Madang Province

Wanbel: Conflict, Reconciliation and Personhood among the Sam People, Madang Province David Eric Troolin Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy In the Discipline of Anthropology, School of Social Sciences University of Adelaide May 2018 Contents Figures ........................................................................................................................................ 5 Abstract ...................................................................................................................................... 6 Declaration ................................................................................................................................. 8 Acknowledgements .................................................................................................................... 9 Glossary.................................................................................................................................... 10 Chapter 1: Wanbel among the Sam people ............................................................................... 16 A glimpse of wanbel ......................................................................................................... 16 The Sam people and the researcher ................................................................................ 17 Wanbel in Papua New Guinea ......................................................................................... 27 Problematising wanbel ................................................................................................... -

Health&Medicalinfoupdate8/10/2017 Page 1 HEALTH and MEDICAL

HEALTH AND MEDICAL INFORMATION The American Embassy assumes no responsibility for the professional ability or integrity of the persons, centers, or hospitals appearing on this list. The names of doctors are listed in alphabetical, specialty and regional order. The order in which this information appears has no other significance. Routine care is generally available from general practitioners or family practice professionals. Care from specialists is by referral only, which means you first visit the general practitioner before seeing the specialist. Most specialists have private offices (called “surgeries” or “clinic”), as well as consulting and treatment rooms located in Medical Centers attached to the main teaching hospitals. Residential areas are served by a large number of general practitioners who can take care of most general illnesses The U.S Government assumes no responsibility for payment of medical expenses for private individuals. The Social Security Medicare Program does not provide coverage for hospital or medical outside the U.S.A. For further information please see our information sheet entitled “Medical Information for American Traveling Abroad.” IMPORTANT EMERGENCY NUMBERS AMBULANCE/EMERGENCY SERVICES (National Capital District only) Police: 112 / (675) 324-4200 Fire: 110 St John Ambulance: 111 Life-line: 326-0011 / 326-1680 Mental Health Services: 301-3694 HIV/AIDS info: 323-6161 MEDEVAC Niugini Air Rescue Tel (675) 323-2033 Fax (675) 323-5244 Airport (675) 323-4700; A/H Mobile (675) 683-0305 Toll free: 0561293722468 - 24hrs Medevac Pacific Services: Tel (675) 323-5626; 325-6633 Mobile (675) 683-8767 PNG Wide Toll free: 1801 911 / 76835227 – 24hrs Health&MedicalInfoupdate8/10/2017 Page 1 AMR Air Ambulance 8001 South InterPort Blvd Ste. -

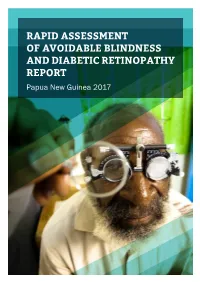

RAPID ASSESSMENT of AVOIDABLE BLINDNESS and DIABETIC RETINOPATHY REPORT Papua New Guinea 2017

RAPID ASSESSMENT OF AVOIDABLE BLINDNESS AND DIABETIC RETINOPATHY REPORT Papua New Guinea 2017 RAPID ASSESSMENT OF AVOIDABLE BLINDNESS AND DIABETIC RETINOPATHY PAPUA NEW GUINEA, 2017 1 Acknowledgements The Rapid Assessment of Avoidable Blindness (RAAB) + Diabetic Retinopathy (DR) was a Brien Holden Vision Institute (the Institute) project, conducted in cooperation with the Institute’s partner in Papua New Guinea (PNG) – PNG Eye Care. We would like to sincerely thank the Fred Hollows Foundation, Australia for providing project funding, PNG Eye Care for managing the field work logistics, Fred Hollows New Zealand for providing expertise to the steering committee, Dr Hans Limburg and Dr Ana Cama for providing the RAAB training. We also wish to acknowledge the National Prevention of Blindness Committee in PNG and the following individuals for their tremendous contributions: Dr Jambi Garap – President of National Prevention of Blindness Committee PNG, Board President of PNG Eye Care Dr Simon Melengas – Chief Ophthalmologist PNG Dr Geoffrey Wabulembo - Paediatric ophthalmologist, University of PNG and CBM Mr Samuel Koim – General Manager, PNG Eye Care Dr Georgia Guldan – Professor of Public Health, Acting Head of Division of Public Health, School of Medical and Health Services, University of PNG Dr Apisai Kerek – Ophthalmologist, Port Moresby General Hospital Dr Robert Ko – Ophthalmologist, Port Moresby General Hospital Dr David Pahau – Ophthalmologist, Boram General Hospital Dr Waimbe Wahamu – Ophthalmologist, Mt Hagen Hospital Ms Theresa Gende -

2021 Budget Volume 1.Pdf

2021 NATIONAL BUDGET VOLUME 1 ECONOMIC AND DEVELOPMENT POLICIES For the year ending 31st December 2021 PRESENTED BY HON. IAN LING-STUCKEY, CMG, MP MINISTER FOR TREASURY ON THE OCCASION OF THE PRESENTATION OF THE 2021 NATIONAL BUDGET i 2021 National Budget, Volume 1 Contents CHAPTER 1: ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENTS AND OUTLOOK ..................................................... 7 1.1 WORLD ECONOMIC GROWTH AND OUTLOOK – DRASTIC ECONOMIC DETERIORATION, SLOW AND UNCERTAIN RECOVERY PROSPECTS DURING THE GREAT LOCKDOWN ................................................................................................... 7 1.2 EXCHANGE RATE DEVELOPMENTS .................................................................... 17 1.3 DOMESTIC ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENTS AND OUTLOOK ................................. 18 1.4 2021 ECONOMIC OUTLOOK ........................................................................................... 22 1.5 LABOUR MARKET .................................................................................................. 26 1.6 MONETARY DEVELOPMENTS .................................................................................. 29 1.7 CONSUMER PRICE INDEX ....................................................................................... 30 1.8 BALANCE OF PAYMENTS AND INTERNATIONAL RESERVES..................................... 34 1.9 RISKS TO MACROECONOMIC STABILITY ................................................................. 36 CHAPTER 2: FISCAL STRATEGY AND OUTLOOK ................................................................. -

Papua New Guinea: Featuring the Kenu & Kundu Festival

Papua New Guinea: Featuring the Kenu & Kundu Festival 11 Days Papua New Guinea: Featuring the Kenu & Kundu Festival Experience the energy of Papua New Guinea on this spectacular 11-day trip that includes the vibrant Kenu and Kundu Festival — one of the country's top cultural highlights! Once a year in November over 40 tribes paddle from their remote island homes to Alotau, where they gather to celebrate the region's drums and canoes. Hear the traditional beats of PNG as you witness canoe races, sing-sings, ritual exchanges, and vivid performances that combine ritual and revelry. This special departure also explores tropical Tufi and the scenic Western Highlands — home to the famous Asaro Mudmen. Details Testimonials Arrive: Brisbane, Australia "We experienced great adventures in this seldom visited and wonderful land." Depart: Brisbane, Australia John P. Duration: 11 Days "This was my 10th trip with MT Sobek and I hope to Group Size: 6–16 Guests do more!" Maria B. Minimum Age: 13 Years Old Activity Level: . REASON #01 REASON #02 REASON #03 MT Sobek has been offering unique Our itinerary has been crafted in This itinerary is one of the few to and immersive adventures in Papua consultation with expert local guides include access to the amazing New Guinea for 3 years — with who understand the complexities Kenu and Kundu festival, an every departure a sell-out success. of traveling in Papua New Guinea. annual event with over 600 tribes. ACTIVITIES LODGING CLIMATE Immersive cultural encounters, Enjoy stays in comfortable hotels, In the lowland and coastal areas fjord cruising with opportunities rated among Papua New Guinea's it will be hot with high humidity. -

Annex 4 Inception Report

ANNEX 4 INCEPTION REPORT TRAINING COURSE TITLE: Intellectual & Developmental Disabilities in Community Activities: 201984534J002 1 General Information 1 Name of Country : Papua New Guinea 2 Area (sq, km) : 462.84Km2 3 Life Expectancy : 65.54 years 4 Infant Mortality Rate : 43.222 deaths per 1000 lifes 5 Maternal Mortality Rate: Papua New Guinea (PNG) is a low–middle-income country located immediately to the north of Australia where the estimated maternal mortality rate is 215 per 100,000 live births: 6 Literacy Rate: Papua New Guinea Literacy Rate 2000-2019. Adult literacy rate is the percentage of people ages 15 and above who can both read and write with understanding a short simple statement about their everyday life. Papua New Guinea literacy rate for 2010 was 61.60%, a 4.26% increase from 2000 7 Population Broken down by: District Age (10 years) Income Level (Rich, Middle, Poor, Poorest) 8 Education System (Number of schools students in each District) At present, there were more than 1 million students and over 32,000 teachers in more than 6,100 institutions in the national education system of Papua New Guinea. There had been tremendous progress in increasing access to education since the educational reforms began in 1993. There are 12 years of school education comprising six years of primary and six of secondary, with cycles of four and two years. The school year starts in January. The International Education Agency of Papua New Guinea is responsible for about 20 private schools that operate all around Papua New Guinea 9 Health System -

Papua New Guinea: Tufi, New Ireland & Milne Bay | X-Ray Mag Issue #50

Tufi, New Ireland & Milne Bay PapuaText and photos by Chritopher New Bartlett Guinea 35 X-RAY MAG : 50 : 2012 EDITORIAL FEATURES TRAVEL NEWS WRECKS EQUIPMENT BOOKS SCIENCE & ECOLOGY TECH EDUCATION PROFILES PHOTO & VIDEO PORTFOLIO travel PNG Is there another country Located just south of the Equator anywhere with so much and to the north of Australia, Papua New Guinea (PNG) is a diversity? The six million diver’s paradise with the fourth inhabitants of this nation of largest surface area of coral reef mountains and islands are ecosystem in the world (40,000km2 spread over 463,000km2 of of reefs, seagrass beds and man- groves in 250,000km2 of seas), and mountainous tropical for- underwater diversity with 2,500 ests and speak over 800 species of fish, corals and mol- different languages (12 luscs. There are more dive sites percent of the world total). than you can shake a stick at with many more to be discovered and Papua New Guinea occu- barely a diver on them. The dive pies half of the third largest centres are so far apart that there island in the world as well is only ever one boat at any dive site. as 160 other islands and It is one of the few places left in Moorish idoll (above); There are colorful cor- 500 named cays. the world where a diver can see als everywhere (left); Schools of fish under the dive boat in the harbor (top). PREVIOUS PAGE: Clown anemonefish on sea anemone 36 X-RAY MAG : 50 : 2012 EDITORIAL FEATURES TRAVEL NEWS WRECKS EQUIPMENT BOOKS SCIENCE & ECOLOGY TECH EDUCATION PROFILES PHOTO & VIDEO PORTFOLIO CLOCKWISE FROM LEFT: Diver and whip corals on reef; Beach view at Tufi; View of the fjords of travel PNG from the air PNG the misty clouds at the swath of trees below, occasionally cut by the hairline crack of a path or the meandering swirls of a river. -

Provincial Scoping Review Report Enga Province November 2020

Provincial Scoping Review Report Enga Province November 2020 Dendrobium engae 1 | Page Disclaimer Copyright © 2020 Global Green Growth Institute Jeongdong Building 19F 21-15 Jeongdong-gil Jung-gu, Seoul 04518 Republic of Korea This report was produced as part of a scoping review exercise conducted in three provinces: Enga, Milne Bay and New Ireland. Sections 1-4 of all three reports are similar as they contain information that is common to all three provinces. The Global Green Growth Institute does not make any warranty, either express or implied, or assumes any legal liability or responsibility for the accuracy, completeness, or any third party’s use or the results of such use of any information, apparatus, product, or process disclosed of the information contained herein or represents that its use would not infringe privately owned rights. The text of this publication may be reproduced in whole or in part and in any form for educational or non-profit uses, provided that acknowledgement of the source is made. The views and opinions of the authors expressed herein do not necessarily state or reflect those of the Global Green Growth Institute. 2 | Page Description of image on the front page Dendrobium engae, commonly known as the Enga Dendrobium, is a rare orchid that is endemic to the highlands of Papua New Guinea. It is a medium-sized epiphyte that grows on large tree branches at elevations of 1800 to 3500 meters in cool to cold climates. It is more commonly found in Enga Province, as compared to other highlands provinces, and therefore, is depicted on the Enga Provincial Flag. -

ROAD MANAGEMENT in PAPUA NEW GUINEA: an EVALUATION of a DECADE of AUSTRALIAN SUPPORT 2007–2017 February 2018

ROAD MANAGEMENT IN PAPUA NEW GUINEA: AN EVALUATION OF A DECADE OF AUSTRALIAN SUPPORT 2007–2017 February 2018 OFFICE OF DEVELOPMENT EFFECTIVENESS dfat.gov.au/ode © Commonwealth of Australia 2018 ISBN 978-0-9954465-2-6 Authors: David Slattery, Matthew Dornan, John Lee. Published by the Australian Government Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade, Canberra, 2018. Disclaimer: The views contained in this report do not necessarily represent those of the Australian Government. With the exception of the Commonwealth Coat of Arms and where otherwise noted all material presented in this document is provided under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Australia (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/au/) licence. The details of the relevant licence conditions are available on the Creative Commons website (accessible using the links provided) as is the full legal code for the CC BY 3.0 AU licence (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/au/ legalcode). The document must be attributed as Office of Development Effectiveness, Road Management in Papua New Guinea: An Evaluation of a Decade of Australian Support 2007–2017, Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade, Canberra, 2018. This document is online at: dfat.gov.au/ode For further information, contact: Office of Development Effectiveness Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade GPO Box 887 Canberra ACT 2601 Phone: (02) 6178 4000 Facsimile: (02) 6178 6076 Internet: dfat.gov.au/ode Cover photo: Kassam Pass, Highlands Highway, Eastern Highlands Province. At the time of evaluation fieldwork, a landslip was threatening to cut off access to the Highlands region at this pass. The Office of Development Effectiveness (ODE) The Office of Development Effectiveness (ODE) is a unit within the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade which monitors the quality and assesses the impact of the Australian aid program. -

Dilemmas of Development

Dilemmas of Development Published by ANU E Press The Australian National University Canberra ACT 0200, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at http://epress.anu.edu.au National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Title: Dilemmas of development : the social and economic impact of the Porgera gold mine, 1989-1994 / Colin Filer, editor. ISBN: 9781922144416 (pbk.) 9781922144423 (ebook) Notes: Includes bibliographical references and index. Subjects: Gold mines and mining--Social aspects--Papua New Guinea--Porgera. Gold mines and mining--Economic aspects--Papua New Guinea--Porgera. Porgera (Papua New Guinea)--Social conditions. Porgera (Papua New Guinea)--Economic conditions. Other Authors/Contributors: Filer, Colin. National Research Institute (Papua New Guinea) Economics and Management. Dewey Number: 338.274109953 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. This edition © 2012 ANU E Press Contents Tables, figures and maps vi Contributors ix Abbreviations x Acknowledgments xi 1. Introduction 1 Colm Filer 2. Social change in the Porgera Valley 19 Susanne Bonnell 3. The economic impact of the mine 88 GlennBanks 4. The landowner relocation programme 128 Susanne Bonnell 5. Gardens and wantoks 160 GlennBanks 6. The next round of relocation 191 GlennBanks 7. Business as unusual 222 Glenn Banks 8. Porgera-whence