Sedimentary Rocks, Stratigraphy, and Geologic Time

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bedrock Geology Glossary from the Roadside Geology of Minnesota, Richard W

Minnesota Bedrock Geology Glossary From the Roadside Geology of Minnesota, Richard W. Ojakangas Sedimentary Rock Types in Minnesota Rocks that formed from the consolidation of loose sediment Conglomerate: A coarse-grained sedimentary rock composed of pebbles, cobbles, or boul- ders set in a fine-grained matrix of silt and sand. Dolostone: A sedimentary rock composed of the mineral dolomite, a calcium magnesium car- bonate. Graywacke: A sedimentary rock made primarily of mud and sand, often deposited by turbidi- ty currents. Iron-formation: A thinly bedded sedimentary rock containing more than 15 percent iron. Limestone: A sedimentary rock composed of calcium carbonate. Mudstone: A sedimentary rock composed of mud. Sandstone: A sedimentary rock made primarily of sand. Shale: A deposit of clay, silt, or mud solidified into more or less a solid rock. Siltstone: A sedimentary rock made primarily of sand. Igneous and Volcanic Rock Types in Minnesota Rocks that solidified from cooling of molten magma Basalt: A black or dark grey volcanic rock that consists mainly of microscopic crystals of pla- gioclase feldspar, pyroxene, and perhaps olivine. Diorite: A plutonic igneous rock intermediate in composition between granite and gabbro. Gabbro: A dark igneous rock consisting mainly of plagioclase and pyroxene in crystals large enough to see with a simple magnifier. Gabbro has the same composition as basalt but contains much larger mineral grains because it cooled at depth over a longer period of time. Granite: An igneous rock composed mostly of orthoclase feldspar and quartz in grains large enough to see without using a magnifier. Most granites also contain mica and amphibole Rhyolite: A felsic (light-colored) volcanic rock, the extrusive equivalent of granite. -

Sediment and Sedimentary Rocks

Sediment and sedimentary rocks • Sediment • From sediments to sedimentary rocks (transportation, deposition, preservation and lithification) • Types of sedimentary rocks (clastic, chemical and organic) • Sedimentary structures (bedding, cross-bedding, graded bedding, mud cracks, ripple marks) • Interpretation of sedimentary rocks Sediment • Sediment - loose, solid particles originating from: – Weathering and erosion of pre- existing rocks – Chemical precipitation from solution, including secretion by organisms in water Relationship to Earth’s Systems • Atmosphere – Most sediments produced by weathering in air – Sand and dust transported by wind • Hydrosphere – Water is a primary agent in sediment production, transportation, deposition, cementation, and formation of sedimentary rocks • Biosphere – Oil , the product of partial decay of organic materials , is found in sedimentary rocks Sediment • Classified by particle size – Boulder - >256 mm – Cobble - 64 to 256 mm – Pebble - 2 to 64 mm – Sand - 1/16 to 2 mm – Silt - 1/256 to 1/16 mm – Clay - <1/256 mm From Sediment to Sedimentary Rock • Transportation – Movement of sediment away from its source, typically by water, wind, or ice – Rounding of particles occurs due to abrasion during transport – Sorting occurs as sediment is separated according to grain size by transport agents, especially running water – Sediment size decreases with increased transport distance From Sediment to Sedimentary Rock • Deposition – Settling and coming to rest of transported material – Accumulation of chemical -

Part 629 – Glossary of Landform and Geologic Terms

Title 430 – National Soil Survey Handbook Part 629 – Glossary of Landform and Geologic Terms Subpart A – General Information 629.0 Definition and Purpose This glossary provides the NCSS soil survey program, soil scientists, and natural resource specialists with landform, geologic, and related terms and their definitions to— (1) Improve soil landscape description with a standard, single source landform and geologic glossary. (2) Enhance geomorphic content and clarity of soil map unit descriptions by use of accurate, defined terms. (3) Establish consistent geomorphic term usage in soil science and the National Cooperative Soil Survey (NCSS). (4) Provide standard geomorphic definitions for databases and soil survey technical publications. (5) Train soil scientists and related professionals in soils as landscape and geomorphic entities. 629.1 Responsibilities This glossary serves as the official NCSS reference for landform, geologic, and related terms. The staff of the National Soil Survey Center, located in Lincoln, NE, is responsible for maintaining and updating this glossary. Soil Science Division staff and NCSS participants are encouraged to propose additions and changes to the glossary for use in pedon descriptions, soil map unit descriptions, and soil survey publications. The Glossary of Geology (GG, 2005) serves as a major source for many glossary terms. The American Geologic Institute (AGI) granted the USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service (formerly the Soil Conservation Service) permission (in letters dated September 11, 1985, and September 22, 1993) to use existing definitions. Sources of, and modifications to, original definitions are explained immediately below. 629.2 Definitions A. Reference Codes Sources from which definitions were taken, whole or in part, are identified by a code (e.g., GG) following each definition. -

Beachrock, in Schwartz, ML, Ed., Encyclopedia of Coastal Science

Turner, RJ. 2005. Beachrock, in Schwartz, ML, ed., Encyclopedia of Coastal Science. Kluwer Academic Publishers, The Netherlands. Pp. 183-186. BEACHROCK Formation and Distribution of Beachrock Beachrock is defined by Scoffin and Stoddart (1987, 401) as "the consolidated deposit that results from lithification by calcium carbonate of sediment in the intertidal and spray zones of mainly tropical coasts." Beachrock units form under a thin cover of sediment and generally overlie unconsolidated sand, although they may rest on any type of foundation. Maximum rates of subsurface beachrock cementation are thought to occur in the area of the beach that experiences the most wetting and drying - below the foreshore in the area of water table excursion between the neap low and high tide levels (Amieux et al, 1989; Higgins, 1994). Figure B49 shows a beachrock formation displaying typical attributes. Figure B49 Multiple unit beachrock exposure at barrio Rio Grande de Aguada, Puerto Rico. The sculpted morphology, development of a nearly vertical landward edge, and dark staining of outer surface by cyanobacteria indicate that this beachrock has experience extended exposure. Landward relief and imbricate morphology of beachrock units define shore- parallel runnels that impound seawater (photo R. Turner). There are a number of theories regarding the process of beach sand cementation. Different mechanisms of cementation appear to be responsible at different localities. The primary mechanisms proposed for the origin of beachrock cements are as follows: 1) -

Rocks and Soil Materials

Science Benchmark: 04:03 Earth materials include rocks, soils, water, and gases. Rock is composed of minerals. Earth materials change over time from one form to another. These changes require energy. Erosion is the movement of materials and weathering is the breakage of bedrock and larger rocks into smaller rocks and soil materials. Soil is continually being formed from weathered rock and plant remains. Soil contains many living organisms. Plants generally get water and minerals from soil. Standard III: Students will understand the basic properties of rocks, the processes involved in the formation of soils, and the needs of plants provided by soil. Shared Reading Getting to Know Rocks and Soil We live on a rocky world! Rocks are all around us. We live on rocks even though we can’t always see them. These rocks are sometimes hidden deeply beneath our feet, and sometimes they are exposed on Earth’s surface so we can see them. On mountaintops, where the soil is very thin, rocks often poke through. All rocks are made of mixtures of different minerals. Minerals are the building blocks from which rocks are made. People who study rocks make observations of rocks they discover. They identify the different minerals in the rocks they find. How can they do this? Each mineral has a certain color (or colors), appearance, shape, hardness, texture, crystal pattern, and possibly a smell that sets it apart from another. As scientists test each mineral's characteristics, they are able to tell which minerals are in the rocks. Rocks can change over a period of time. -

Sedimentary Rock Formation Models

Sedimentary Rock Formation Models 5.7 A Explore the processes that led to the formation of sedimentary rock and fossil fuels. The Formation Process Explained • Formation of these rocks is one of the important parts of the rock cycle. For millions of years, the process of deposition and formation of these rocks has been operational in changing the geological structure of earth and enriching it. Let us now see how sedimentary rocks are formed. Weathering The formation process begins with weathering of existent rock exposed to the elements of nature. Wind and water are the chisels and hammers that carve and sculpt the face of the Earth through the process of weathering. The igneous and metamorphic rocks are subjected to constant weathering by wind and water. These two elements of nature wear out rocks over a period of millions of years creating sediments and soil from weathered rocks. Other than this, sedimentation material is generated from the remnants of dying organisms. Transport of Sediments and Deposition These sediments generated through weathering are transported by the wind, rivers, glaciers and seas (in suspended form) to other places in the course of flow. They are finally deposited, layer over layer by these elements in some other place. Gravity, topographical structure and fluid forces decide the resting place of these sediments. Many layers of mineral, organics and chemical deposits accumulate together for years. Layers of different deposits called bedding features are created from them. Crystal formation may also occur in these conditions. Lithification (Compaction and Cementation) Over a period of time, as more and more layers are deposited, the process of lithification begins. -

Weathering Transportation Deposition Sediments Sedimantary Rocks

Weathering Transportation Deposition Uplift & exposure Sediments Igneous rocks (extrusive) Lithification Pyroclastic (Compaction and material Cementation) Consolidation Sedimantary rocks Igneous rocks (ıntrusion) Metamorphic Crystallization rocks Melting Prof.Dr.Kadir Dirik Lecture Notes Prof.Dr.Kadir Dirik Lecture Notes Sediment and Sedimentary Rocks The term sediment refers to (1) all solid particles of preexisting rocks yielded by mechanical and chemical weathering, (2) minerals derived from solutions containing materials dissolved during chemical weathering and (3) minerals extracted from sea water by organisms to build their shell. Sedimentary rock is simply any rock composed of sediments. 2 Prof.Dr.Kadir Dirik Lecture Notes Sedimentary rocks cover about two thirds of the continents and most of the seafloor, except spreading ridges. All rocks are important to understand the Earth history, but sedimentary rocks play a special role because they preserve evidence of surface processes responsible for them.By studying sedimentary rocks we can determine past distribution of streams, lakes, deserts, glaciers, and shorelines. They also make interferences about ancient climates and biosphere. In adition, some sediments and sedimentary rocks are themselves natural resources, or they are the host for resources such as petroleum and natural gas. Depositional Processes (Çökelme Süreçleri) Weathering & Erosion, Transportation, Deposition / Sedimentation and Diagenesis. Weathering & Erosion Weathering and erosion are the fundamental processes in the origin of sediment. During this process two types of sediments are produced: detrital sediments and chemical sediments. 3 Prof.Dr.Kadir Dirik Lecture Notes Ayrışma/bozunma erozyon Taşınma ve Çökelme/depolanma Gömülme ve taşlaşma 4 Prof.Dr.Kadir Dirik Lecture Notes Detrital Sediments. are all particles derived from any type of weathering. -

Concretions, Nodules and Weathering Features of the Carmelo Formation

Concretions, nodules and weathering features of the Carmelo Formation The features that characterize a sedimentary rock can form at chemical origin and include nodules and concretions. diverse times and under very different conditions. Geologists Deformational features result from the bending, buckling, or divide these features into four classes. Depositional features breaking of sedimentary strata by external forces. Surficial form while the sediment is accumulating. They can tell a much (weathering) features develop in a rock at or near the about the ancient environment of deposition and include many surface where it is subject to groundwater percolation. These examples in the Carmelo Formation. Diagenetic features features can reflect both physical and chemical processes. a develop after the sediment has accumulated and can include number of examples exist in the rocks of Point Lobos. (See link the transition from sediment to rock. They typically have a to The Rocks of Point Lobos for further descriptions). Depositional Diagenetic Deformational Surficial Features that form as Features that form after Features that develop Features that form while the the sediment the sediment was anytime after deposition rock is exposed at or near accumulates deposited until it becomes and reflect the bending, the present-day land surface a rock swirling, or breaking of the stratification Examples: Examples: Examples: Examples: Bedding (layering, Nodules “Convolute lamination” Iron banding stratification) Concretions Slump structure Honeycomb Grain size Lithification (rock Tilting weathering Grain organization formation) Folds Color change (grading, pebble Faults orientation, imbrication) Ripple marks Ripple lamination Trace fossils Erosional scours Channels Features of a sedimentary rock sorted according to their origin. -

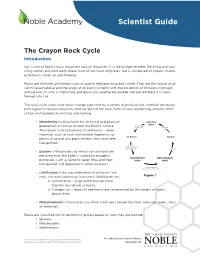

Scientist Guide the Crayon Rock Cycle

Scientist Guide The Crayon Rock Cycle Introduction Soil is one of Earth’s most important natural resources. It is the bridge between the living and non- living worlds and ultimately where most of our food originates. Soil is composed of organic materi- al (humus), water, air and minerals. Rocks are mixtures of minerals such as quartz, feldspar, mica and calcite. They are the source of all soil mineral material and the origin of all plant nutrients with the exception of nitrogen, hydrogen and carbon. As rock is chemically and physically weathered, eroded and precipitated, it is trans- formed into soil. The rock cycle shows how rocks change over time by a variety of physical and chemical processes (see Figure 1). Natural processes that are part of the rock cycle include weathering, erosion, lithifi- cation, metamorphism, melting and cooling. • Weathering involves both the chemical and physical IGNEOUS ROCK Weathering breakdown of rock at or near the Earth’s surface. and Erosion Cooling This results in accumulation of sediments – loose materials, such as rock and mineral fragments, or Sediment Magma pieces of animal and plant remains that have been transported. Lithification (Compaction and Cementation) Melting • Erosion is the process by which soil and rock are removed from the Earth’s surface by exogenic SEDIMENTARY METAMORPHIC processes, such as wind or water flow, and then ROCK ROCK transported and deposited in other locations. Metamorphism (Heat and/or Pressure) • Lithification is the transformation of sediment into rock. The main processes involved in lithification are: Figure 1. o Cementation – large sediments are held together by natural cements. -

Sedimentary Rocks and Sedimentary Basins

Reading Sedimentary • Stanley, S.M., 2015, Sedimentary Environments, – Ch. 5. Earth Systems History Rocks and • On Ecampus Sedimentary Basins What is a Sedimentary Basin? Sedimentary Rocks – A thick accumulation of sediment – Necessary conditions: •Intro 1. A depression (subsidence) • Origin of sedimentary rocks 2. Sediment Supply – Clastic Rocks – Carbonate Sedimentary Rocks • Interpreting Sedimentary Rocks – Environment of deposition • Implications for the Petroleum System World Map of Sedimentary Basins Where are the Sedimentary Basins? 6 A B Watts Our Peculiar Planet: The Rock Cycle Liquid Water and Plate Tectonics Hydrologic Cycle Tectonics http://www.dnr.sc.gov/geology/images/Rockcycle-pg.pdf 8 SEDIMENT 3 Basic Types of Sedimentary Rocks • Unconsolidated products of Weathering & Erosion • Detrital ( = Clastic) – Loose sand, gravel, silt, mud, etc. – Made of Rock Fragments – Transported by rivers, wind, glaciers, currents, etc. • Biochemical – Formed by Organisms • Sedimentary Rock: – Consolidated sediment • Chemical – Lithified sediment – Precipitated from Chemical Solution Detrital Material Transported by a River Formation of a Sedimentary Rocks 1. Weathering – mechanical & chemical 2. Transport – by river, wind, glacier, ocean, etc. 3. Deposition – in a point bar, moraine, beach, ocean basin, etc 4. Lithification – loose sediment turns to solid rock Processes during Transport • 1. Sorting – Grain size is related to energy of transport – Boulders high energy environment – Mud low energy Facies: Rock unit characteristic of a depositional -

Ecological Succession and Biogeochemical Cycles

Chapter 10: Changes in Ecosystems Lesson 10.1: Ecological Succession and Biogeochemical Cycles Can a plant really grow in hardened lava? It can if it is very hardy and tenacious. And that is how succession starts. It begins with a plant that must be able to grow on new land with minimal soil or nutrients. Lesson Objectives ● Outline primary and secondary succession, and define climax community. ● Define biogeochemical cycles. ● Describe the water cycle and its processes. ● Give an overview of the carbon cycle. ● Outline the steps of the nitrogen cycle. ● Understand the phosphorus cycle. ● Describe the ecological importance of the oxygen cycle. Vocabulary ● biogeochemical cycle ● groundwater ● primary succession ● carbon cycle ● nitrogen cycle ● runoff ● climax community ● nitrogen fixation ● secondary succession ● condensation ● phosphorus cycle ● sublimation ● ecological succession ● pioneer species ● transpiration ● evaporation ● precipitation ● water cycle Introduction Communities are not usually static. The numbers and types of species that live in them generally change over time. This is called ecological succession. Important cases of succession are primary and secondary succession. In Earth science, a biogeochemical cycle or substance turnover or cycling of substances is a pathway by which a chemical substance moves through both biotic (biosphere) and abiotic (lithosphere, atmosphere, and hydrosphere) compartments of Earth. A cycle is a series of change which comes back to the starting point and which can be repeated. The term "biogeochemical" tells us that biological, geological and chemical factors are all involved. The circulation of chemical nutrients like carbon, oxygen, nitrogen, phosphorus, calcium, and water etc. through the biological and physical world are known as biogeochemical cycles. In effect, the element is recycled, although in some cycles there may be places (called reservoirs) where the element is accumulated or held for a long period of time (such as an ocean or lake for water). -

How Fast Do Rocks Form?

The Proceedings of the International Conference on Creationism Volume 1 Print Reference: Volume 1:II, Page 197-204 Article 44 1986 How Fast Do Rocks Form? Kurt Wise Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.cedarville.edu/icc_proceedings DigitalCommons@Cedarville provides a publication platform for fully open access journals, which means that all articles are available on the Internet to all users immediately upon publication. However, the opinions and sentiments expressed by the authors of articles published in our journals do not necessarily indicate the endorsement or reflect the views of DigitalCommons@Cedarville, the Centennial Library, or Cedarville University and its employees. The authors are solely responsible for the content of their work. Please address questions to [email protected]. Browse the contents of this volume of The Proceedings of the International Conference on Creationism. Recommended Citation Wise, Kurt (1986) "How Fast Do Rocks Form?," The Proceedings of the International Conference on Creationism: Vol. 1 , Article 44. Available at: https://digitalcommons.cedarville.edu/icc_proceedings/vol1/iss1/44 HOW FAST DO ROCKS FORM? Kurt Wise ABSTRACT Geologists typically maintain that the crustal rocks cannot be formed in less than millions of years. Creationists typically maintain that at catastrophic rates, all the earth's surface rocks could form rapidly. Several rock types are studied to test the validity of the creationist claim. Examples include basalts, granites, metamorphic rocks, shales, limestones and sandstones. Non-creationist geologists typically maintain that the rocks on the earth's surface could only be created over long periods of time. It is claimed that it would be quite impossi ble to form all the rocks of the earth in a 6,000 year history.