John Eliot and the Algonquins of Eastern Massachusetts, 1646–90

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gookin's History of the Christian Indians

AN HISTORICAL ACCOUNT OF THE DOINGS AND SUFFERINGS OF THE CHRISTIAN INDIANS IN NEW ENGLAND, IN THE YEARS 1675, 1676, 1677 IMPARTIALLY DRAWN BY ONE WELL ACQUAINTED WITH THAT AFFAIR, A ND PRESENTED UNTO THE RIGHT HONOURABLE THE CORPORATION RESIDING IN LONDON, APPOINTED BY THE KING'S MOST EXCELLENT MAJESTY FOR PROMOTING THE GOSPEL AMONG THE INDIANS IN AMERICA. PRELIMINARY NOTICE. IN preparing the following brief sketch of the principal incidents in the life of the author of “The History of the Christian Indians,” the Publishing Committee have consulted the original authorities cited by the -American biographical writers, and such other sources of information as were known to them, for the purpose of insuring greater accuracy; but the account is almost wholly confined to the period of his residence in New England, and is necessarily given in the most concise manner. They trust, that more ample justice will yet be done to his memory by the biographer and the historian. DANIEL GOOKIN was born in England, about A. D. 1612. As he is termed “a Kentish soldier” by one of his contemporaries, who was himself from the County of Kent, 1 it has been inferred, with good reason, that Gookin was a native of that county. In what year he emigrated to America, does not clearly appear; but he is supposed to have first settled in the southern colony of Virginia, from whence he removed to New England. Cotton Mather, in his memoir of Thompson, a nonconformist divine of Virginia, has the following quaint allusion to our author “A constellation of great converts there Shone round him, and his heavenly glory were. -

The Autobiography of Increase Mather

The Autobiography of Increase Mather I-DÎTED BY M. G. HALL j^ STRETCH a point to call this maTiuscript an W autobiography. Actually it i.s a combinatioa of aiito- biograpliy and political tract and journal, in which the most formal part comes first and the rest was added on lo it as occasion offered. But, the whole is certainly auto- biographical and covers Increase Mather's life faithfull}'. It was tlie mainstay of Cotton Mather's famous biograpliy Pareniator, which appeared in 1724, and of Kenneth Mur- dock's Increase Miiîher, whicli was published two liundred and one years later.^ Printing the autobiography Jiere is in no way designed to improve or correct Mather's biog- raphers. They have done well by him. But their premises and purposes were inevitabiy different from liis. I'he present undertaking is to let Increase Matlier also be lieard on tlie subject of himself. Readers who wish to do so are invited to turn witliout more ado to page 277, where tliey may read the rjriginal without interruption. For tjiose who want to look before they leap, let me remind tliem of tlie place Increase Mather occu[!Íes in tlie chronology of his family. Three generations made a dy- nasty extraordhiary in any country; colossal in the frame of ' Cotton Msther, Pami'.at'^r. Mnnoirs if Remarkables in the Life and Death o/ the F.vtr- MemorahU Dr. Increase Múíker (Boston, 1724). Kenneth B. Murdock, Incrfasr Mathfr, the Foremost .Imerican Puritan (Cambridge, 1925)- Since 1925 three books bearing importantly on hicrcase Mather have been published: Thomas J. -

The Word of God in Puritan New England: Seventeenth-Century Perspectives on the Nature and Authority of the Bible

Andrews University Seminay Studies, Spring 1980, Vol. XVIII, No. 1, 1-16 Copyright O 1980 by Andrews University Press. THE WORD OF GOD IN PURITAN NEW ENGLAND: SEVENTEENTH-CENTURY PERSPECTIVES ON THE NATURE AND AUTHORITY OF THE BIBLE ALLENCARDEN Biola College La Mirada, California Those who would truly understand what American Puritanism was all about would do well to give heed to the sources from which the Puritans drew their ideas. It should come as no surprise that the principal source of Puritan ideology was the Bible itself. What is sur- prising is the way in which some historians, most notably the late Perry Miller, have ignored or minimized the Puritans' biblicism while attempting to unearth non-biblical roots for Puritan concepts. Instead of accepting the Puritans' own statements about their reliance on Scripture, Miller turned to more humanistic sources. In his massive work The New England Mind: The 17th Century, he makes passing comments about the Puritan acceptance of Scripture, but his emphasis is on "the four quarries from which the Puritan scholars carved out their principal ideas and doctrines"-European Protestantism, special interests and preoccupations of the seven- teenth century, humanism, and medieval scholasticism. ' The Puritans obviously did not operate in a cultural vacuum; they could not help but be influenced by the intellectual and cultural climate of their day. Miller, however, apparently ignored their own appraisal of the role of Scripture in their lives and 'For the quotations in this and the following introductory paragraph, plus other related concepts, see Perry Miller, The New England Mind: The 17th Centuy, 2d ed. -

The Legacies of King Philip's War in the Massachusetts Bay Colony

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 1987 The legacies of King Philip's War in the Massachusetts Bay Colony Michael J. Puglisi College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Puglisi, Michael J., "The legacies of King Philip's War in the Massachusetts Bay Colony" (1987). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539623769. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-f5eh-p644 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS While the most advanced technology has been used to photograph and reproduce this manuscript, the quality of the reproduction is heavily dependent upon the quality of the material submitted. For example: • Manuscript pages may have indistinct print. In such cases, the best available copy has been filmed. • Manuscripts may not always be complete. In such cases, a note will indicate that it is not possible to obtain missing pages. • Copyrighted material may have been removed from the manuscript. In such cases, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, and charts) are photographed by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each oversize page is also filmed as one exposure and is available, for an additional charge, as a standard 35mm slide or as a 17”x 23” black and white photographic print. -

The Tribal Warriors; and the Powwows, Who Were Wise Men and Shamans

63 A TRIPARTITE POLITICAL SYSTEM AMONG CHRISTIAN INDIANS OF EARLY MASSACHUSETTS Susan L. MacCulloch University of California, Berkeley In seventeenth century colonial Massachusetts there existed for a brief but memorable period about twenty towns of various size and success inhabited entirely by Christian Indians. These towns of converts were islands in a sea of opposing currents, for unconverted Indians scorned them, and un- trusting English opposed them. The towns and their inception is a story in itself (see Harvey [MacCulloch] 1965:M.A. thesis); but it will suffice here to note that in the established Indian towns the inhabitants dressed in English clothes, were learning or already practicing their "callings" or trades, and were earnest Puritan churchgoers. They were able to read and write in Indian (and some in English), took logic and theology courses from Rev. John Eliot in the summer, and sent their promising young men to the Indian College at Harvard. Furthermore, they had extensive farmed land, live- stock, and orchards, and participated in a market economy with the somewhat incredulous colonists. The picture, in short, was not the one usually de- scribed in grammar school history books of the red savage faced by the colonists. One of the most interesting aspects of the Praying Towns, as they were called, was their unique political system, made up of the English colonial and the traditional tribal systems; and superimposed on both of these was a biblical arrangement straight out of Moses. In order to fully appreciate this tripartite political system some background information about the native and colonial systems is helpful. -

Proceedings of the Semi-Annual Meeting

Proceedings of the Semi-annual Meeting APRIL iS, I95I AT THE CLUB OV ODD VOLUMES, BOSTON HE semi-annual meeting of the Anieric^in Antiquarian TSociety was held at the Club of Odd Volumes, jj Mount \'ernon Street, Boston, Massachusetts, April 18, 1951, at io.45 o'clock. Samuei Eliot Morison, President of the Society, presided at the meeting. The following members were present; John MeKinstry Mcrriam, George Parker Winship, Clarence Saunders Brigham, Samuel Eliot Morison, Daniel Waldo Lincoln, Mark Antony DeWolfe Howe, Russeil Sturgis i^aine, James Melville Hunnewcll, Stephen Willard Phillips, Stewart Mitchell, Edward Larocque Tinker, Claude Moore I'\icss, Foster Stearns, CiifTord Kenyon Shipton, Theron Johnson Damon, Keyes DeWitt Melcalf, Albert White Rice, Hamilton \'aughan Bail, William Greene Roelker, Henry Rouse V'iets, Walter Muir Whitehiil, Samuel Eoster Damon, William Alexander Jackson, Roger Woicott, Ernest Caulfield, George Russeli Stobbs, Arthur Adams, Richard LeBaron Bowen, Bertram Kimball Little, Caricton Rubira Richmond, Philip Howard Cook, Theodore Bolton, L Bernard Coiien, Harris Dunscombe Colt, Jr., Elmer Tindall Hutchinson. The Secretary read the calí for the meeting, and it was voted to dispense with the reading of the records of the Annual Meeting of October, 1950. 2 AMERICAN ANTIQUARIAN SOCIETY [April, The Director read the report of the Council. It was voted to accept the report and refer it to the Committee on Publications. The election of new members being in order, the President announced the following recommendations by the Council for membership in the Society: Lyman Henry Butterfield, Princeton, N. J. Arthur Harrison Cole, Cambridge, Mass. George Talbot Goodspeed, Boston, Mass. -

Early Puritanism in the Southern and Island Colonies

Early Puritanism in the Southern and Island Colonies BY BABETTE M. LEVY Preface NE of the pleasant by-products of doing research O work is the realization of how generously help has been given when it was needed. The author owes much to many people who proved their interest in this attempt to see America's past a little more clearly. The Institute of Early American History and Culture gave two grants that enabled me to devote a sabbatical leave and a summer to direct searching of colony and church records. Librarians and archivists have been cooperative beyond the call of regular duty. Not a few scholars have read the study in whole or part to give me the benefit of their knowledge and judgment. I must mention among them Professor Josephine W, Bennett of the Hunter College English Department; Miss Madge McLain, formerly of the Hunter College Classics Department; the late Dr. William W. Rockwell, Librarian Emeritus of Union Theological Seminary, whose vast scholarship and his willingness to share it will remain with all who knew him as long as they have memories; Professor Matthew Spinka of the Hartford Theological Sem- inary; and my mother, who did not allow illness to keep her from listening attentively and critically as I read to her chapter after chapter. All students who are interested 7O AMERICAN ANTIQUARIAN SOCIETY in problems concerning the early churches along the Atlantic seaboard and the occupants of their pulpits are indebted to the labors of Dr. Frederick Lewis Weis and his invaluable compendiums on the clergymen and parishes of the various colonies. -

The Beginning of Winchester on Massachusett Land

Posted at www.winchester.us/480/Winchester-History-Online THE BEGINNING OF WINCHESTER ON MASSACHUSETT LAND By Ellen Knight1 ENGLISH SETTLEMENT BEGINS The land on which the town of Winchester was built was once SECTIONS populated by members of the Massachusett tribe. The first Europeans to interact with the indigenous people in the New Settlement Begins England area were some traders, trappers, fishermen, and Terminology explorers. But once the English merchant companies decided to The Sachem Nanepashemet establish permanent settlements in the early 17th century, Sagamore John - English Puritans who believed the land belonged to their king Wonohaquaham and held a charter from that king empowering them to colonize The Squaw Sachem began arriving to establish the Massachusetts Bay Colony. Local Tradition Sagamore George - For a short time, natives and colonists shared the land. The two Wenepoykin peoples were allies, perhaps uneasy and suspicious, but they Visits to Winchester were people who learned from and helped each other. There Memorials & Relics were kindnesses on both sides, but there were also animosities and acts of violence. Ultimately, since the English leaders wanted to take over the land, co- existence failed. Many sachems (the native leaders), including the chief of what became Winchester, deeded land to the Europeans and their people were forced to leave. Whether they understood the impact of their deeds or not, it is to the sachems of the Massachusetts Bay that Winchester owes its beginning as a colonized community and subsequent town. What follows is a review of written documentation KEY EVENTS IN EARLY pertinent to the cultural interaction and the land ENGLISH COLONIZATION transfers as they pertain to Winchester, with a particular focus on the native leaders, the sachems, and how they 1620 Pilgrims land at Plymouth have been remembered in local history. -

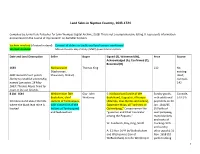

Land Sales in Nipmuc Country.Pdf

Land Sales in Nipmuc Country, 1643-1724 Compiled by Jenny Hale Pulsipher for John Wompas Digital Archive, 2018. This is not a comprehensive listing. It represents information encountered in the course of my research on Swindler Sachem. Sachem involved (if noted in deed) Consent of elders or traditional land owners mentioned Woman involved Massachusetts Bay Colony (MBC) government actions Date and Land Description Seller Buyer Signed (S), Witnessed (W), Price Source Acknowledged (A), ConFirmed (C), Recorded (R) 1643 Nashacowam Thomas King £12 No [Nashoonan, existing MBC General Court grants Shawanon, Sholan] deed; liberty to establish a township, Connole, named Lancaster, 18 May 142 1653; Thomas Noyes hired by town to lay out bounds. 8 Oct. 1644 Webomscom [We Gov. John S: Nodowahunt [uncle of We Sundry goods, Connole, Bucksham, chief Winthrop Bucksham], Itaguatiis, Alhumpis with additional 143-145 10 miles round about the hills sachem of Tantiusques, [Allumps, alias Hyems and James], payments on 20 where the black lead mine is with consent of all the Sagamore Moas, all “sachems of Jan. 1644/45 located Indians at Tantiusques] Quinnebaug,” Cassacinamon the (10 belts of and Nodowahunt “governor and Chief Councelor wampampeeg, among the Pequots.” many blankets and coats of W: Sundanch, Day, King, Smith trucking cloth and sundry A: 11 Nov. 1644 by WeBucksham other goods); 16 and Washcomos (son of Nov. 1658 (10 WeBucksham) to John Winthrop Jr. yards trucking 1 cloth); 1 March C: 20 Jan. 1644/45 by Washcomos 1658/59 to Amos Richardson, agent for John Winthrop Jr. (JWJr); 16 Nov. 1658 by Washcomos to JWJr.; 1 March 1658/59 by Washcomos to JWJr 22 May 1650 Connole, 149; MD, MBC General Court grants 7:194- 3200 acres in the vicinity of 195; MCR, LaKe Quinsigamond to Thomas 4:2:111- Dudley, esq of Boston and 112 Increase Nowell of Charleston [see 6 May and 28 July 1657, 18 April 1664, 9 June 1665]. -

Vital Allies: the Colonial Militia's Use of Indians in King Philip's War, 1675--1676

University of New Hampshire University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository Master's Theses and Capstones Student Scholarship Spring 2011 Vital allies: The colonial militia's use of Indians in King Philip's War, 1675--1676 Shawn Eric Pirelli University of New Hampshire, Durham Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.unh.edu/thesis Recommended Citation Pirelli, Shawn Eric, "Vital allies: The colonial militia's use of Indians in King Philip's War, 1675--1676" (2011). Master's Theses and Capstones. 146. https://scholars.unh.edu/thesis/146 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Scholarship at University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses and Capstones by an authorized administrator of University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. VITAL ALLIES: THE COLONIAL MILITIA'S USE OF iNDIANS IN KING PHILIP'S WAR, 1675-1676 By Shawn Eric Pirelli BA, University of Massachusetts, Boston, 2008 THESIS Submitted to the University of New Hampshire in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts In History May, 2011 UMI Number: 1498967 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. UMT Dissertation Publishing UMI 1498967 Copyright 2011 by ProQuest LLC. -

Wampanoag, Tribespeople “Of the Dawn”

THE WAMPANOAG, TRIBESPEOPLE “OF THE DAWN” “Ye see, Hinnissy, th’ Indyun is bound f’r to give way to th’ onward march iv white civilization. You ’an me, Hinnissy, is th’ white civilization... The’ on’y hope f’r th’ Indyun is to put his house on rollers, an’ keep a team hitched to it, an’, whin he sees a white man, to start f’r th’ settin’ sun.” — Finley Peter Dunne, OBSERVATIONS BY MR. DOOLEY, New York, 1902 HDT WHAT? INDEX WAMPANOAG WAMPANOAG When the English settlements first commenced in New England, that part of its territory, which lies south of New Hampshire, was inhabited by five principal nations of Indians: the Pequots, who lived in Connecticut; the Narragansets, in Rhode Island; the Pawkunnawkuts, or Womponoags, east of the Narragansets and to the north as far as Charles river;1 the Massachusetts, north of Charles river and west of Massachusetts Bay; and the Pawtuckets, north of the Massachusetts. The boundaries and rights of these nations appear not to have been sufficiently definite to be now clearly known. They had within their jurisdiction many subordinate tribes, governed by sachems, or sagamores, subject, in some respects, to the principal sachem. At the commencement of the seventeenth century, they were able to bring into the field more than 18,000 warriors; but about the year 1612, they were visited with a pestilential disease, whose horrible ravages reduced their number to about 1800.2 Some of their villages were entirely depopulated. This great mortality was viewed by the first Pilgrims, as the accomplishment of one of the purposes of Divine Providence, by making room for the settlement of civilized man, and by preparing a peaceful asylum for the persecuted Christians of the old world. -

Calvin Theological Seminary Covenant In

CALVIN THEOLOGICAL SEMINARY COVENANT IN CONFLICT: THE CONTROVERSY OVER THE CHURCH COVENANT BETWEEN SAMUEL RUTHERFORD AND THOMAS HOOKER A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF CALVIN THEOLOGICAL SEMINARY IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY BY SANG HYUCK AHN GRAND RAPIDS, MICHIGAN MAY 2011 CALVIN THEOLOGICAL SEMINARY 3233 Burton SE • Grand Rapids, Michigan. 49546-4301 800388-6034 Jax: 616957-8621 [email protected] www.calvinserninary.edu This dissertation entitled COVENANT IN CONFLICT: THE CONTROVERSY OVER THE CHURCH COVENANT BETWEEN SAMUEL RUTHERFORD AND THOMAS HOOKER written by SANG HYUCK AHN and submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy has been accepted by the faculty of Calvin Theological Seminary upon the recommendation ofthe undersigned readers: Carl R Trueman, Ph.D. David M. Rylaarsda h.D. Date Acting Vice President for Academic Affairs Copyright © 2011 by Sang Hyuck Ahn All rights reserved To my Lord, the Head of the Church Soli Deo Gloria! CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ix ABSTRACT xi CHAPTER 1. INTRODUCTION 1 I. Statement of the Thesis 1 II. Statement of the Problem 2 III. Survey of Scholarship 6 IV. Sources and Outline 10 CHAPTER 2. THE HISTORICAL CONTEXT OF THE RUTHERFORD-HOOKER DISPUTE ABOUT CHURCH COVENANT 15 I. The Church Covenant in New England 15 1. Definitions 15 1) Church Covenant as a Document 15 2) Church Covenant as a Ceremony 20 3) Church Covenant as a Doctrine 22 2. Secondary Scholarship on the Church Covenant 24 II. Thomas Hooker and New England Congregationalism 31 1. A Short Biography 31 2. Thomas Hooker’s Life and His Congregationalism 33 1) The England Period, 1586-1630 33 2) The Holland Period, 1630-1633: Paget, Forbes, and Ames 34 3) The New England Period, 1633-1647 37 III.