Urban Fragment As Collective Memory

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sterling Bank Building, 283 Portage Avenue (1910-1911) Frank S

283 PORTAGE AVENUE STERLING BANK BUILDING City of Winnipeg Historical Buildings & Resources Committee Researcher: M. Peterson November 2016 283 PORTAGE AVENUE – STERLING BANK BUILDING Winnipeg’s first retail district was actually the Hudson’s Bay Company’s (HBC) fur trading post, Upper Fort Garry, at the foot of today’s Main Street and had served as the commercial centre for the small settlement since its construction in the 1830s. By the 1850s and 1860s, the beginnings of a commercial district had begun to develop around the corner of Portage Avenue and Main Street. The HBC finally began selling off its Main Street frontage south of Portage Avenue in the 1870s. It was then that this area began to fill with small- and medium-size commercial enterprises (Plate 1). In 1883, the Clarendon Hotel was built on the northwest corner of Portage Avenue and Donald Street. It was one of early Winnipeg’s best-known buildings, surrounded for many years by bald prairie and small structures. The hotel (Plate 2) was a massive brick and stone structure, five storeys high with retail space on the ground floor of both the Donald Street and Portage Avenue frontages. Built in the Second Empire style, the building was finished with a mansard roof and corner turret. It was, for many years, one of only a handful of significant buildings not located in the Exchange District or on Main Street and virtually the only major building on Portage Avenue’s north side. Soon after the turn-of-the-century, fundamental changes occurred to refocus the retail sector from Main Street onto Portage Avenue. -

President's Message

President’s Message As my first term as President of Heritage Winnipeg draws to a close and I reflect on all that has been accomplished in the past two years, it is truly invigorating. Major challenges have been met and those successes drive the will to continue the effort to pursue new opportunities and to reach for even higher goals. It is a pleasure to be associated with such a hard working team of directors, partners and of course, our dynamic Executive Director, Cindy Tugwell. Many, many years ago Heritage Winnipeg spearheaded a study on the Upper Fort Garry site and today, due to the tremendous effort of The Friends of Upper Fort Garry in which Heritage Winnipeg plays an active part, this very special heritage site has been saved for today and for tomorrow. Much work is still required and many more dollars will need to be raised but the site is now secure and with dedication and hard work, the Upper Fort Garry site will once again come to life. This is a great example of the vision, patience and tenacity that is so often required when one seeks to preserve a small piece of our heritage. Kudos to those with the vision and all those who could understand and support that vision, you can be proud of what has been achieved and look ahead to even more exciting times with what can be achieved. Doors Open continues to be a key public program for Heritage Winnipeg. Thank you to all the volunteers, all the building owners for opening their doors so the building’s stories can be told and all the Winnipeggers who spend the weekend learning more about our great city and its architecture and history. -

U:\HSMBC\Exchange\Exchange District CIS Final January 10, 2001

THE EXCHANGE DISTRICT NATIONAL HISTORIC SITE OF CANADA COMMEMORATIVE INTEGRITY STATEMENT It is not the individual buildings themselves. but the historical process of bringing together large numbers of heritage structures illustrating important themes within a tightly defined area which makes the Exchange District a distinctive place. Block after block of brick warehouses, rows of financial structures, key groupings of skyscrapers - in total, these built resources evoke a sense of the type of place which Winnipeg was during its most formative years, late in the 19th and early in the 20th centuries, when Winnipeg rose to metropolitan status (Dana Johnson 1996 Historic Sites and Monuments Board Agenda paper). January 10, 2001 Page i TABLE OF CONTENTS APPROVAL PAGE ............................................................ i TABLE OF CONTENTS........................................................ii 1 INTRODUCTION ...................................................... 1 1.1 National Historic Sites ................................................... 2 1.2 Historic Districts as National Historic Sites................................... 2 1.3 Commemorative Integrity................................................. 3 1.4 Purpose of the Commemorative Integrity Statement ............................ 4 2 THE EXCHANGE DISTRICT NATIONAL HISTORIC SITE .................... 5 2.1 National Historic Designation of the Exchange District.......................... 5 2.2 The Exchange District: Historical Overview .................................. 6 3 STATEMENT -

Annual Report 2011-2012

INCOPORATED 1978 Annual Report 2011-2012 #509 - 63 Albert Street Winnipeg, MB R3B 1G4 P. 204.942.2663 F. 204.942.2094 [email protected] www.heritagewinnipeg.com Heritage Winnipeg is funded in part by the City of Winnipeg and by the Province of Manitoba 2011-20122011-2012 Annual Annual Report Report 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Program Elements Administration and Planning 1 Education and Information 3 Projects and Fundraising 6 Advocacy and Conservation 8 2011-2012 Board of Directors 15 2011-20122011-2012 Annual Annual Report Report 2 1.0 ADMINISTRATION AND PLANNING: 1.1 Provincial and Municipal Annual Support 2011-12: The application for annual funding from the Province of Manitoba, Department of Culture, Heritage and Tourism was submitted. Included in the proposal were our goals and objectives within our program elements (75%) was received in July and the remaining 25% portion in December. This support is essential in helping to sustain the organization’s projects and programs. Heritage Winnipeg did approach the Province again during the year in hopes of increasing our annual support, and will continue to advocate an increase in order to sustain the current programs. Thank you to the Provincial Historic Resources Department for all their assistance throughout the year. Provincial support goes towards educational projects and programs such as our Educational Outreach Program, Manitoba Day Celebrations, Annual Preservation Awards Program, and Doors Open Winnipeg. Thank you to all the staff at the Historic Resources Branch for all their support throughout the year. Heritage Winnipeg’s annual City of Winnipeg grant was $25,000 in support of our various projects and programs in 2011-12. -

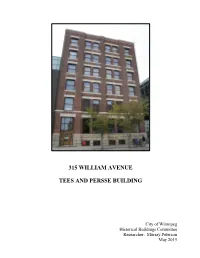

Tees and Persse Building, 315 William Avenue, 6Th Floor Showing Square Beam and Post Structural System, 2001

315 WILLIAM AVENUE TEES AND PERSSE BUILDING City of Winnipeg Historical Buildings Committee Researcher: Murray Peterson May 2015 315 WILLIAM AVENUE – TEES AND PERSSE BUILDING In 1884, these young men [James Tees and John B. Persse] decided to form a partnership and go into business on their own account in the hope of making sufficient money to bring brides to Winnipeg. Considerable discussion ensued as to what line of business to enter and as both had confidence thousands of white people would eventually settle on the prairies and in British Columbia, they decided to enter the Brokerage or Agency business. The partners felt it would be economically impossible for Eastern Manufacturers to individually introduce and promote the sale of their products throughout the vast, sparsely settled territory of the West, whereas under an Agency arrangement, there would be no cost to the Manufacturer until a sale was made and then only brokerage.1 The last sentence of the above quote accurately describes how Winnipeg grew from an outpost of the fur trade into Western Canada’s premier centre in the first decade of the 20th century. The brokerage or warehouse trade became synonymous with Winnipeg. Many fortunes were made from humble beginnings because of the city's location between the growing population centres to the west and established manufacturing centres to the east. The City became known as the “Gateway City” and “The Chicago of the North” because of its heavy reliance on its wholesale sector to provide employment and fuel overall economic growth. In 1905-1906, Tees and Persse Limited, which had been organized in 1902 as a limited liability company,2 constructed its second new warehouse in two years. -

457 Main Street Confederation Life Building

457 MAIN STREET CONFEDERATION LIFE BUILDING City of Winnipeg Historical Buildings & Resources Committee Researcher: M. Peterson April 2020 This building embodies the following heritage values as described in the Historical Resources By-law, 55/2014 (consolidated update July 13, 2016): (a) This building was completed by 1912 during the early years of Winnipeg’s dramatic growth phase that lasted until 1915; (b) It is associated with Confederation Life Association, influential international insurer; (c) It features a wealth of architectural detailing and is an excellent example of the Chicago Style of architecture with Sullivanesque detailing; (d) It is an important example of steel and reinforced concrete construction and and terra cotta cladding; (e) The building stands within the Exchange District National Historic Site and has defined its rounded corner of Main Street since construction; and (f) The building’s exterior has suffered little alteration. 457 MAIN STREET – CONFEDERATION LIFE BUILDING Winnipeg’s Main Street had its beginnings as a winding, approximately 32.0-kilometre trail, 40 metres wide, running north-south along the Red River connecting the Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC) posts of Upper Fort Garry and Lower Fort Garry.1 Referred to as the King’s Highway, the Garry Road and Garry Street, it was used by horses and Red River carts during the fur trade era to automobiles in the 20th century.2 Regardless of the mode of transportation on it, Main Street developed into one of regions most important commercial thoroughfares. Until 1849, the HBC enjoyed a complete monopoly on trade in the region, which prohibited citizens from operating private commercial ventures. -

Heritage District Revitalization

Kevin Complido Sustainable Heritage Case Study CDNS 5003 Class Presentation November 21, 2017 Heritage District Revitalization The Urban Campus Leading Sustainability: Red River College and the Rehabilitation of the Former Union Bank Building in Winnipeg’s Historic Exchange District Heritage District Revitalization 45° Image of Winnipeg’s Exchange District NHS. Red River College Fig.1: owned spaces in red, Paterson GlobalFoods Institute in bright red. Google Maps (n.d.) Heritage District Revitalization Description O B J E C T I V E S • Role in social, cultural, environmental and economic sustainability shaping in downtown revitalization. • Rehabilitation and expansion of Red River College’s Exchange District Campus efforts • Converted to mixed-use Culinary institute, food programs, and student residences (RRC, (n.d., [blogs.rrc.ca/culex/about/pgi]) L A R G E R T H E M E S • Urban conservation and the role of the ‘urban campus’ in shaping city development (Peters, 2017; Rodwell, 2003) • Leading by example in revitalizing a heritage district’s potential through socio-cultural sustainability efforts Heritage District Revitalization View of Paterson in relation to Old Market Square (OMS). Visible are Paterson’s student residences tower, new culinary institute interventions, and building’s relationship to significant surrounding urban + cultural spaces. Fig.2: Merkeley [@gmerk] (2017) Heritage District Revitalization Lessons R O L E O F T H E S T A K E H O L D E R S • Success having much to do with stakeholders’ support and will to see the project done well. S U C C E S S E S • RRC & Paterson GlobalFoods Institute’s contribution to Exchange District revitalization & sustainability. -

283 Portage Avenue Sterling Bank Building

283 PORTAGE AVENUE STERLING BANK BUILDING City of Winnipeg Historical Buildings & Resources Committee Researcher: M. Peterson November 2016 283 PORTAGE AVENUE – STERLING BANK BUILDING Winnipeg’s first retail district was actually the Hudson’s Bay Company’s (HBC) fur trading post, Upper Fort Garry, at the foot of today’s Main Street and had served as the commercial centre for the small settlement since its construction in the 1830s. By the 1850s and 1860s, the beginnings of a commercial district had begun to develop around the corner of Portage Avenue and Main Street. The HBC finally began selling off its Main Street frontage south of Portage Avenue in the 1870s. It was then that this area began to fill with small- and medium-size commercial enterprises (Plate 1). In 1883, the Clarendon Hotel was built on the northwest corner of Portage Avenue and Donald Street. It was one of early Winnipeg’s best-known buildings, surrounded for many years by bald prairie and small structures. The hotel (Plate 2) was a massive brick and stone structure, five storeys high with retail space on the ground floor of both the Donald Street and Portage Avenue frontages. Built in the Second Empire style, the building was finished with a mansard roof and corner turret. It was, for many years, one of only a handful of significant buildings not located in the Exchange District or on Main Street and virtually the only major building on Portage Avenue’s north side. Soon after the turn-of-the-century, fundamental changes occurred to refocus the retail sector from Main Street onto Portage Avenue.