A Christian Rejection of Capital Punishment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

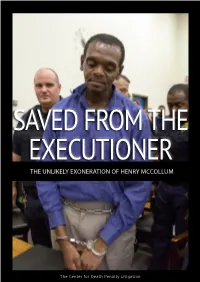

SAVED from the EXECUTIONER: the Unlikely Exoneration of Henry

SAVED FROM THE EXECUTIONER THE UNLIKELY EXONERATION OF HENRY MCCOLLUM The Center for Death Penalty Litigation HENRY MCCOLLUM f all the men and women on death row in North Carolina, Henry McCollum’s guilty verdict looked O airtight. He had signed a confession full of grisly details. Written in crude and unapologetic language, it told the story of four boys, he among them, raping 11-year-old Sabrina Buie, and suffocating her by shoving her own underwear down her throat. He had confessed again in front of television cameras shortly after. His younger brother, Leon Brown, also admitted involvement in the crime. Both were sen- tenced to death in 1984. Leon was later resentenced to life in prison. But Henry remained on death row for 30 years and became Exhibit A in the defense of the death penalty. U.S. Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia pointed to the brutality of Henry’s crime as a reason to continue capital punishment nation- wide. During North Carolina legislative elections in 2010, Henry’s face showed up on political flyers, the example of a brutal rapist and child killer who deserved to be executed. What almost no one saw — not even his top-notch defense attorneys — was that Henry McCollum was inno- cent. He had nothing to do with Sabrina’s murder. Nor did Leon. In 2014, both were exonerated by DNA evidence and, in 2015, then-Gov. Pat McCrory granted them a rare LEON BROWN pardon of innocence. Though Henry insisted on his innocence for decades, the truth was painfully slow to emerge: Two intellectually disabled teenagers – naive, powerless, and intimidated by a cadre of law enforcement officers – had been pres- sured into signing false confessions. -

Prison Guards and the Death Penalty

BRIEFING PAPER Prison guards and the death penalty Introduction and elsewhere.3 In Japan, in the latter stages before execution, all communication between prisoners or When we think about the people affected by the death between guards and prisoners is forbidden.4 penalty, we may not think about guards on death rows. But these officials, whether they oversee prisoners In 2014, the Texas prison guards union appealed for awaiting execution or participate in the execution itself, better death row prisoner conditions, because the can be deeply affected by their role in helping to put a guards faced daily danger from prisoners made mentally person to death. ill by solitary confinement and who had ‘nothing to lose’.5 In this environment, routine safety practices were imposed that dehumanised prisoners and guards alike, Guards on death row such as every exit of a cell requiring a strip search. Persons sentenced to death are usually considered Guards protested that their own dignity was undermined among the most dangerous prisoners and are placed by the obligation to look at ‘one naked inmate after in the highest security conditions. Prison guards are another’6 all day. frequently suspicious of death row prisoners, are particularly vigilant around them,1 and experience death row as a dangerous place. Interactions with prisoners Despite the stark conditions, death rows are still places Harsh prison conditions can make things worse not where human connections form. In all but the most only for prisoners but also for guards. The mental extreme solitary settings, guards engage with prisoners health of death row prisoners frequently deteriorates regularly, bringing them food and accompanying them and they may suffer from ‘death row phenomenon’, the when they leave their cells (for example to exercise, ‘condition of mental and emotional distress brought on receive visits or attend court hearings). -

The Spanish Garrote

he members of parliament, meeting in Cadiz in 1812, to draft the first Spanish os diputados reunidos en Cádiz en 1812 para redactar la primera Constitución Constitution, were sensitive to the irrational torment that those condemned to Española, fueron sensibles a los irracionales padecimientos que hasta entonces capital punishment had up until then suffered when they were punished. In De- the spanish garrote sufrían los condenados a la pena capital en el momento de ser ajusticiados, y cree CXXVIII, of 24 January, they recognized that “no punishment will be trans- en el Decreto CXXVIII, de 24 de enero, reconocieron que “ninguna pena ha ferable to the family of the person that suffers it; and wishing at the same time that Lde ser trascendental a la familia del que la sufre; y queriendo al mismo tiempo Tthe torment of the criminals should not offer too repugnant a spectacle to humanity que el suplicio de los delincuentes no ofrezca un espectáculo demasiado and to the generous nature of the Spanish nation (…) ” they agreed to abolish the repugnante a la humanidad y al carácter generoso de la Nación española transferable punishment of hanging, replacing it with the garrote. (...) ” acordaron abolir la trascendental pena de horca, sustituyéndola por la Some days earlier, on January 10th, the City Council of Toledo, in compliance de garrote. with a decision of the Real Junta Criminal [Royal Criminal Committee] of the city, Ya unos días antes, el 10 de enero, el ayuntamiento de Toledo, en cum- agreed to the construction of two garrotes and approved the regulations for the plimiento de una providencia de la Real Junta Criminal de la ciudad, acordó construction of the platform. -

The Peformative Grotesquerie of the Crucifixion of Jesus

THE GROTESQUE CROSS: THE PERFORMATIVE GROTESQUERIE OF THE CRUCIFIXION OF JESUS Hephzibah Darshni Dutt A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2015 Committee: Jonathan Chambers, Advisor Charles Kanwischer Graduate Faculty Representative Eileen Cherry Chandler Marcus Sherrell © 2015 Hephzibah Dutt All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Jonathan Chambers, Advisor In this study I argue that the crucifixion of Jesus is a performative event and this event is an exemplar of the Grotesque. To this end, I first conduct a dramatistic analysis of the crucifixion of Jesus, working to explicate its performativity. Viewing this performative event through the lens of the Grotesque, I then discuss its various grotesqueries, to propose the concept of the Grotesque Cross. As such, the term “Grotesque Cross” functions as shorthand for the performative event of the crucifixion of Jesus, as it is characterized by various aspects of the Grotesque. I develop the concept of the Grotesque Cross thematically through focused studies of representations of the crucifixion: the film, Jesus of Montreal (Arcand, 1989), Philip Turner’s play, Christ in the Concrete City, and an autoethnographic examination of Cross-wearing as performance. I examine each representation through the lens of the Grotesque to define various facets of the Grotesque Cross. iv For Drs. Chetty and Rukhsana Dutt, beloved holy monsters & Hannah, Abhishek, and Esther, my fellow aliens v ACKNOWLEDGMENTS St. Cyril of Jerusalem, in instructing catechumens, wrote, “The dragon sits by the side of the road, watching those who pass. -

Performative Violence and Judicial Beheadings of Native Americans in Seventeenth-Century New England

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 2014 "Thus Did God Break the Head of that Leviathan": Performative Violence and Judicial Beheadings of Native Americans in Seventeenth-Century New England Ian Edward Tonat College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the Indigenous Studies Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Tonat, Ian Edward, ""Thus Did God Break the Head of that Leviathan": Performative Violence and Judicial Beheadings of Native Americans in Seventeenth-Century New England" (2014). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539626765. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-ycqh-3b72 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “Thus Did God Break the Head of That Leviathan”: Performative Violence and Judicial Beheadings of Native Americans in Seventeenth- Century New England Ian Edward Tonat Gaithersburg, Maryland Bachelor of Arts, Carleton College, 2011 A Thesis presented to the Graduate Faculty of the College of William and Mary in Candidacy for the Degree of Master of Arts Lyon G. Tyler Department of History The College of William and Mary May, 2014 APPROVAL PAGE This Thesis is submitted -

Governor Ryan's Capital Punishment Moratorium and the Executioner's Confession: Views from the Governor's Mansion to Death Row

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by St. John's University School of Law St. John's Law Review Volume 75 Number 3 Volume 75, Summer 2001, Number 3 Article 4 March 2012 Governor Ryan's Capital Punishment Moratorium and the Executioner's Confession: Views from the Governor's Mansion to Death Row Norman L. Greene Governor George H. Ryan Donald Cabana Jim Dwyer Martha Barnett See next page for additional authors Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.stjohns.edu/lawreview Recommended Citation Greene, Norman L.; Ryan, Governor George H.; Cabana, Donald; Dwyer, Jim; Barnett, Martha; and Davis, Evan (2001) "Governor Ryan's Capital Punishment Moratorium and the Executioner's Confession: Views from the Governor's Mansion to Death Row," St. John's Law Review: Vol. 75 : No. 3 , Article 4. Available at: https://scholarship.law.stjohns.edu/lawreview/vol75/iss3/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at St. John's Law Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in St. John's Law Review by an authorized editor of St. John's Law Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Governor Ryan's Capital Punishment Moratorium and the Executioner's Confession: Views from the Governor's Mansion to Death Row Authors Norman L. Greene, Governor George H. Ryan, Donald Cabana, Jim Dwyer, Martha Barnett, and Evan Davis This article is available in St. John's Law Review: https://scholarship.law.stjohns.edu/lawreview/vol75/iss3/4 GOVERNOR RYAN'S CAPITAL PUNISHMENT MORATORIUM AND THE EXECUTIONER'S CONFESSION: VIEWS FROM THE GOVERNOR'S MANSION TO DEATH ROW NORMAN L. -

Death Row Witness Reveals Inmates' Most Chilling Final Moments

From bloodied shirts and shuddering to HEADS on fire: Death Row witness reveals inmates' most chilling final moments By: Chris Kitching - Mirror Online Ron Word has watched more than 60 Death Row inmates die for their brutal crimes - and their chilling final moments are likely to stay with him until he takes his last breath. Twice, he looked on in horror as flames shot out of a prisoner's head - filling the chamber with smoke - when a hooded executioner switched on an electric chair called "Old Sparky". Another time, blood suddenly appeared on a convicted murderer's white shirt, caking along the leather chest strap holding him to the chair, as electricity surged through his body. Mr Word was there for another 'botched' execution, when two full doses of lethal drugs were needed to kill an inmate - who shuddered, blinked and mouthed words for 34 minutes before he finally died. And then there was the case of US serial killer Ted Bundy, whose execution in 1989 drew a "circus" outside Florida State Prison and celebratory fireworks when it was announced that his life had been snuffed out. Inside the execution chamber at the Florida State Prison near Starke (Image: Florida Department of Corrections/Doug Smith) 1 of 19 The electric chair at the prison was called "Old Sparky" (Image: Florida Department of Corrections) Ted Bundy was one of the most notorious serial killers in recent history (Image: www.alamy.com) Mr Word witnessed all of these executions in his role as a journalist. Now retired, the 67-year-old was tasked with serving as an official witness to state executions and reporting what he saw afterwards for the Associated Press in America. -

Capital Punishment in Eighteenth-Century Spain

Capital Punishment in Eighteenth-Century Spain Ruth PIKE The purpose ofthis article is to examine the theory and practice ofcapital punislunenl in eighleenlh-century Spain and to evaluate Spanish justice within the broader framework ofthe European criminal justice system of the time. Spanish penal practices differed widely from English and French ones, and Spanish law was less given to the death penalty. Simple theft or larceny was not punished by the death sentence in Spain, and there was no additional legislation creating more capital offenses as in eighleenlh century England. Spanish law reserved the death penalty for certain categories of crimes and criminals and their number remained the same throughout the early modern period. Preference was given to sentences to penal labor in the presidios. With its emphasis on judicial discretion and its consideration ofextenuating circumstances, the Spanish system ofjustice can best be described as a calculated combination ofpunislunent , utilitarian practices and mercy. The data analyzed in this article are drawn from contemporary writings and judicial records extant in the Madrid archives. Cet article examine Ia theorie et Ia pratique de Ia peine capita/e. dans/' Espagne du XVIII' siecle, en considerant Ia justice espagnole dans un contexte plus large de Ia justice criminelle europeenne de/' epoque. La pratique penale espagnole differait sensiblement de cel/es de l'Angleterre et de Ia France. C' est ainsi qu' elle y etait moins dispasee que dans ces pays aenvisager Ia peine de mort. Et il n'y eut pas de Legislation additionne/le, accroissant le nombre de crimes capitaux, comme dans/' Angletterre du XVIII' siecle. -

Tableaux Morts: Execution, Cinema, and Galvanistic Fantasies Alison Griffiths Baruch College, CUNY

Tableaux Morts: Execution, Cinema, and Galvanistic Fantasies Alison Griffiths Baruch College, CUNY ales of punishment, incarceration, torture, and execution have enthralled audiences since time immemorial; even witnessing actual executions was within the realm of the possible up until the dawn of the twentieth century, as death penalties Twere carried out in public. A rich, macabre visual culture evolved around spectacularized exe- cutions: images of barbaric deaths have been recorded in artworks, woodcuts, paintings, draw- ings, photographs, lithographs, and motion pictures. This essay explores how the invention of cinema responded to the longue durée that is visualized executions. But rather than construct a genealogy of execution on film, I instead want to hone in on a method of execution that is vir- tually isomorphic with cinema’s invention—electrocution. Coming of age at roughly the same time, electrocution and cinema were exemplars of technological modernity and were shaped by shared histories of popular and scientific display.1 Thomas Alva Edison was instrumental in the development of both motion pictures and electrocution. Without his expert testimony in the legal Earlier versions of this essay were presented as invited talks at the “Powers of Display: Cinemas of Investigation” conference at the University of Chicago, at the “Europe on Display” conference at McGill University, and at Utrecht University. I am grateful to William Boddy, Tom Gunning, Frank Kessler, Matthew Solomon, Paul Spehr, Haidee Wasson, and an anonymous reader from the Republics of Letters for assistance preparing this essay for publication. 1 Kristen Whissel, Picturing American Modernity: Traffic, Technology, and the Silent Cinema (Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 2008), 154. -

MEDICAL ACCOUNT of the CRUCIFIXION SIMPLIFIED & AMENDED from Douglas Jacoby and Alex Mnatzaganian*

MEDICAL ACCOUNT OF THE CRUCIFIXION SIMPLIFIED & AMENDED From Douglas Jacoby and Alex Mnatzaganian* Hanging, electrocution, knee-capping, gas chamber: these punishments are feared. They all happen today, and we shudder as we think of the horror and pain. But as we shall see, these ordeals pale into insignificance compare with the bitter fate of Jesus Christ: crucifixion. Few persons are crucified today (except by ISIS and various other terrorists). For us the cross remains confined to ornaments and jewelry, stained-glass windows, romanticized pictures and statues portraying a serene death. Crucifixion was a form of execution refined by the Romans to a precise art. It was carefully conceived to produce a slow death with maximum pain. It was a public spectacle intended to deter other would-be criminals. It was a death to be feared. Sweat like blood Luke 22:24 says of Jesus, “and being in anguish, he prayed more earnestly, and his sweat was like drops of blood falling to the ground.” The sweat was unusually intense because his emotional state was unusually intense. Dehydration coupled with exhaustion further weakened him. (Note: the scriptures nowhere say that Jesus was sweating blood.) Beating It was in this condition that Jesus faced the first physical abuse: punches and slaps to the face and head while blindfolded. Unable to anticipate the blows, Jesus was badly bruised, his mouth and eyes possibly injured. The psychological effects of the false trials should not be underestimated. Consider that Jesus faced them bruised, dehydrated, exhausted, possibly in shock. Flogging In the previous 12 hours Jesus had suffered emotional trauma, rejection by his closest friends, a cruel beating, and a sleepless night during which he had to walk miles between unjust hearings. -

St. Lawrence's Death on a Grill: Fact Or Fiction?

Rev. Lawrence B. Porter St. Lawrence’s Death on a Grill: Fact or Fiction? An Update on the Controversy Lawrence (Latin laurentius, literally “laurelled”) is the name of the archdeacon of the church of Rome who was martyred in Rome in the year 258 during the persecution of Christians ordered by the Emperor Valerian.1 In the century after his martyrdom, devotion to this St. Lawrence developed rapidly and far beyond Rome. More- over, it has continued to grow and spread even up to modern times, finding expression in art, music, literature, geographical exploration, and social life. For example, in the year 1145 the cathedral at Lund, Sweden, was consecrated with Lawrence as its patron. As for the literary influence of the martyrdom of Lawrence, one should note how Lawrence’s steadfast courage in the face of death is celebrated in the fourth canto of Dante’s Paradiso (completed by 1320). And Lawrence’s burning on a grill is the subject of a conversation in one of the tales, the tenth story on the sixth day, in Boccaccio’s collection of short stories called the Decameron (written c. 1348). Too numerous to mention are the representations of Lawrence in the graphic arts. But outstanding among them are the stained glass windows in the cathedral of Bourges, France, which were completed in the year 1230 and illustrate Lawrence’s life as well as his death. logos 20:4 fall 2017 90 logos We should also note the paintings by Fra Angelico and the Venetian painter Titian. More precisely, between 1447 and 1449, Fra Angelico, at the request of Pope Nicholas V, painted for a chapel in the apostolic palace at the Vatican a series of frescoes illustrating the life and death of Lawrence. -

Executioner Identities: Toward Recognizing a Right to Know Who Is Hiding Beneath the Hood

EXECUTIONER IDENTITIES: TOWARD RECOGNIZING A RIGHT TO KNOW WHO IS HIDING BENEATH THE HOOD Ellyde Roko* INTRODUCTION The doctor had more than twenty malpractice suits filed against him.1 Two hospitals had revoked his privileges.2 He testified that he had dyslexia and sometimes confused drug dosages.3 This same doctor also supervised the lethal injections of fifty-four inmates in Missouri over a decade.4 For ten years, the public, the press, and the condemned inmates themselves did not know about the supervising executioner’s qualifications in Missouri.5 In a federal lawsuit challenging the state’s implementation of lethal injection, the Department of Corrections refused to reveal any information about execution team members until a magistrate judge issued a protective order and required team members to answer interrogatories.6 Once the case reached the district court, the judge did not allow testimony because of time constraints.7 The doctor whose problem-plagued history * J.D. Candidate, 2008, Fordham University School of Law; Bachelor of Science in Journalism, 2003, Northwestern University, Medill School of Journalism. I am incredibly grateful to Professor Deborah W. Denno for her invaluable guidance, support, and encouragement on this Note. I also would like to thank Professor Abner Greene and Dr. Mark Heath for their feedback on earlier drafts, and Bill Fish, Karen Kaiser, and Karl Olson for their assistance in obtaining documents. 1. Jeremy Kohler, Behind the Mask of the Execution Doctor: Revelations About Dr. Alan Doerhoff Follow Judge’s Halt of Lethal Injections, St. Louis Post-Dispatch, July 30, 2006, at A1. 2.