Some Notes on Merlin 87

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Queen Guinevere

Ingvarsdóttir 1 Hugvísindasvið Queen Guinevere: A queen through time B.A. Thesis Marie Helga Ingvarsdóttir June 2011 Ingvarsdóttir 2 Háskóli Íslands Hugvísindasvið Enskudeild Queen Guinevere: A queen through time B.A. Thesis Marie Helga Ingvarsdóttir Kt.: 060389-3309 Supervisor: Ingibjörg Ágústsdóttir June 2011 Ingvarsdóttir 3 Abstract This essay is an attempt to recollect and analyze the character of Queen Guinevere in Arthurian literature and movies through time. The sources involved here are Welsh and other Celtic tradition, Latin texts, French romances and other works from the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, Malory’s and Tennyson’s representation of the Queen, and finally Guinevere in the twentieth century in Bradley’s and Miles’s novels as well as in movies. The main sources in the first three chapters are of European origins; however, there is a focus on French and British works. There is a lack of study of German sources, which could bring different insights into the character of Guinevere. The purpose of this essay is to analyze the evolution of Queen Guinevere and to point out that through the works of Malory and Tennyson, she has been misrepresented and there is more to her than her adulterous relation with Lancelot. This essay is exclusively focused on Queen Guinevere and her analysis involves other characters like Arthur, Lancelot, Merlin, Enide, and more. First the Queen is only represented as Arthur’s unfaithful wife, and her abduction is narrated. We have here the basis of her character. Chrétien de Troyes develops this basic character into a woman of important values about love and chivalry. -

The Character Model in Le Morte Darthur

The Character Model in Le Morte Darthur Anat Koplowitz-Breier ([email protected]) BAR-ILAN UNIVERSITY (RAMAT-GAN) Resumen Palabras clave Los personajes de La muerte de Arturo, La muerte de Arturo de Sir Thomas Malory, no se ajustan a la Malory definición estándar típica de los Caracterización personajes del romance. De hecho, Tipo pueden ser ubicados en una especie de Modelo de personaje estado transitorio que ha sido La dama denominado modelo de personaje. Tras La mujer con poderes mágicos dilucidar la naturaleza de tal concepto, este artículo procede a investigar dos modelos relativos a mujeres en La Muerte de Arturo: «La Dama» y «La Mujer con Poderes Mágicos». Abstract Key words The characters in Sir Thomas ’ Le Morte Darthur La Morte ’ do not conform to Malory the standard definition of Romance Characterization personae. In fact, they can be placed in Type a kind of transitional stage which has ’Model been called a ’ Model. After The Lady elucidating the nature of such a The Woman with Magical Power concept, this paper goes on to investigate two ’ Models of women in the Le Morte Darthur: «The Lady» and «The Woman with Magical AnMal Electrónica 25 (2008) Powers». ISSN 1697-4239 In the memory of my beloved teacher Prof. Ruth Reichelberg, who taught me what it means to be an academic person and a true Character Sir Thomas Malory's Morte is a mixture of at least two genres, Romance and Chronicle (Pochoda 1971). As McCarthy writes, his style is not of one piece: «’ matière is the matière of romance, but the sens, the ‘’ is perhaps not» (1988: 148). -

How Geoffrey of Monmouth Influenced the Story of King Arthur

Western Oregon University Digital Commons@WOU Student Theses, Papers and Projects (History) Department of History 6-10-2019 The Creation of a King: How Geoffrey of Monmouth Influenced the Story of King Arthur Marcos Morales II [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.wou.edu/his Part of the Cultural History Commons, Medieval History Commons, and the Medieval Studies Commons Recommended Citation Morales II, Marcos, "The Creation of a King: How Geoffrey of Monmouth Influenced the Story of King Arthur" (2019). Student Theses, Papers and Projects (History). 276. https://digitalcommons.wou.edu/his/276 This Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of History at Digital Commons@WOU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Student Theses, Papers and Projects (History) by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@WOU. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected], [email protected]. The Creation of a King: How Geoffrey of Monmouth Influenced the Story of King Arthur. By: Marcos Morales II Senior Seminar: HST 499 Professor David Doellinger Western Oregon University June 05, 2019 Readers Professor Elizabeth Swedo Professor Bau Hwa Hsieh Copyright © Marcos Morales II Arthur, with a single division in which he had posted six thousand, six hundred, and sixty-six men, charged at the squadron where he knew Mordred was. They hacked a way through with their swords and Arthur continued to advance, inflicting terrible slaughter as he went. It was at this point that the accursed traitor was killed and many thousands of his men with him.1 With the inclusion of this feat between King Arthur and his enemies, Geoffrey of Monmouth shows Arthur as a mighty warrior, one who stops at nothing to defeat his foes. -

Echoes of Legend: Magic As the Bridge Between a Pagan Past And

Winthrop University Digital Commons @ Winthrop University Graduate Theses The Graduate School 5-2018 Echoes of Legend: Magic as the Bridge Between a Pagan Past and a Christian Future in Sir Thomas Malory's Le Morte Darthur Josh Mangle Winthrop University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.winthrop.edu/graduatetheses Part of the Literature in English, British Isles Commons Recommended Citation Mangle, Josh, "Echoes of Legend: Magic as the Bridge Between a Pagan Past and a Christian Future in Sir Thomas Malory's Le Morte Darthur" (2018). Graduate Theses. 84. https://digitalcommons.winthrop.edu/graduatetheses/84 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the The Graduate School at Digital Commons @ Winthrop University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Winthrop University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ECHOES OF LEGEND: MAGIC AS THE BRIDGE BETWEEN A PAGAN PAST AND A CHRISTIAN FUTURE IN SIR THOMAS MALORY’S LE MORTE DARTHUR A Thesis Presented to the Faculty Of the College of Arts and Sciences In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree Of Master of Arts In English Winthrop University May 2018 By Josh Mangle ii Abstract Sir Thomas Malory’s Le Morte Darthur is a text that tells the story of King Arthur and his Knights of the Round Table. Malory wrote this tale by synthesizing various Arthurian sources, the most important of which being the Post-Vulgate cycle. Malory’s work features a division between the Christian realm of Camelot and the pagan forces trying to destroy it. -

Tara Stud's Homecoming King

TUESDAY, 15 DECEMBER 2020 DEIRDRE TO VISIT GALILEO IN 2021 TARA STUD'S A new direction in the extraordinary odyssey of the Japanese HOMECOMING KING mare Deirdre (Jpn) (Harbinger {GB}BReizend {Jpn, by Special Week {Jpn}) began on Monday when the 6-year-old left her adopted home of Newmarket to begin her stud career in Ireland. Her first mating is planned to be with Coolmore's champion sire Galileo (Ire). Bred by Northern Farm and raced by Toji Morita, Deirdre's first three seasons of racing were restricted largely to Japan, where she won five races, including the G1 Shuka Sho. She also took third in the G1 Dubai Turf on her first start outside her native country. Following her return visit to the Dubai World Cup meeting in 2019, Deirdre travelled on to Hong Kong and then to Newmarket, which has subsequently remained her base for an ambitious international campaign. Cont. p6 River Boyne | Benoit photo IN TDN AMERICA TODAY VOLATILE SETTLING IN AT THREE CHIMNEYS By Emma Berry and Alayna Cullen GI Alfred G. Vanderbilt H. winner Volatile (Violence) is new to On part of its 70-mile journey across Ireland, the River Boyne Three Chimneys Farm in 2021. The TDN’s Katie Ritz caught up flows not far from Tara Stud in County Meath, but the stallion with Three Chimneys’ Tom Hamm regarding the new recruit. named in its honour has taken a far more meandering course Click or tap here to go straight to TDN America. simply to return to source. Approaching his sixth birthday, River Boyne (Ire) (Dandy Man {Ire}) is back home from America and about to embark on a stallion career five years after he was sold by his breeder Derek Iceton at the Goffs November Foal Sale. -

Summary of the Perlesvaus Or the High History of the Grail (Probably First Decade of 13Th Century, Certainly Before 1225, Author Unknown)

Summary of the Perlesvaus or The High History of the Grail (probably first decade of 13th century, certainly before 1225, author unknown). Survives in 3 manuscripts, 2 partial copies, and one early print edition Percival starts out as the young adventurous knight who did not fulfill his destiny of achieving the Holy Grail because he failed to ask the Fisher King the question that would heal him, events related in Chrétien's work. The author soon digresses into the adventures of knights like Lancelot and Gawain, many of which have no analogue in other Arthurian literature. Often events and depictions of characters in the Perlesvaus differ greatly from other versions of the story. For instance, while later literature depicts Loholt as a good knight and illegitimate son of King Arthur, in Perlesvaus he is apparently the legitimate son of Arthur and Guinevere, and he is slain treacherously by Arthur's seneschal Kay, who is elsewhere portrayed as a boor and a braggart but always as Arthur's loyal servant (and often, foster brother. Kay is jealous when Loholt kills a giant, so he murders him to take the credit. This backfires when Loholt's head is sent to Arthur's court in a box that can only be opened by his murderer. Kay is banished, and joins with Arthur's enemies, Brian of the Isles and Meliant. Guinevere expires upon seeing her son dead, which alters Arthur and Lancelot's actions substantially from what is found in later works. Though its plot is frequently at variance with the standard Arthurian outline, Perlesvaus did have an effect on subsequent literature. -

Lancelot - the Truth Behind the Legend by Rupert Matthews

Lancelot - The Truth behind the Legend by Rupert Matthews Published by Bretwalda Books at Smashwords Website : Facebook : Twitter This ebook is licensed for your personal enjoyment only. This ebook may not be re-sold or given away to other people. If you would like to share this book with another person, please purchase an additional copy for each person. If you're reading this book and did not purchase it, or it was not purchased for your use only, then please purchase your own copy. Thank you for respecting the hard work of this author. First Published 2013 Copyright © Rupert Matthews 2013 Rupert Matthews asserts his moral rights to be regarded as the author of this book. ISBN 978-1-909698-64-2 CONTENTS Introduction Chapter 1 - Lancelot the Legend Chapter 2 - Lancelot in France Chapter 3 - Lancelot in Britain Conclusion Introduction Of all the Knights of the Round Table, none is so famous as Sir Lancelot. He is both the finest of the Arthurian knights, and the worst. He is the champion of the Round Table, and the reason for its destruction. He is loyal, yet treacherous. Noble, but base. His is a complex character that combines the best and worst of the world of chivalry in one person. It is Sir Lancelot who features in every modern adaptation of the old stories. Be it an historical novel, a Hollywood movie or a British TV series, Lancelot is centre stage. He is usually shown as a romantically flawed hero doomed to eventual disgrace by the same talents and skills that earn him fame in the first place. -

Actions Héroïques

Shadows over Camelot FAQ 1.0 Oct 12, 2005 The following FAQ lists some of the most frequently asked questions surrounding the Shadows over Camelot boardgame. This list will be revised and expanded by the Authors as required. Many of the points below are simply a repetition of some easily overlooked rules, while a few others offer clarifications or provide a definitive interpretation of rules. For your convenience, they have been regrouped and classified by general subject. I. The Heroic Actions A Knight may only do multiple actions during his turn if each of these actions is of a DIFFERENT nature. For memory, the 5 possible action types are: A. Moving to a new place B. Performing a Quest-specific action C. Playing a Special White card D. Healing yourself E. Accusing another Knight of being the Traitor. Example: It is Sir Tristan's turn, and he is on the Black Knight Quest. He plays the last Fight card required to end the Quest (action of type B). He thus automatically returns to Camelot at no cost. This move does not count as an action, since it was automatically triggered by the completion of the Quest. Once in Camelot, Tristan will neither be able to draw White cards nor fight the Siege Engines, if he chooses to perform a second Heroic Action. This is because this would be a second Quest-specific (Action of type B) action! On the other hand, he could immediately move to another new Quest (because he hasn't chosen a Move action (Action of type A.) yet. -

Sir Gawain and the Green Knight As a Loathly Lady Tale by Lauren Chochinov a Thesis Submitted to the Facult

Distressing Damsels: Sir Gawain and the Green Knight as a Loathly Lady Tale By Lauren Chochinov A Thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies of The University of Manitoba In partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of MASTER OF ARTS Department of English University of Manitoba Winnipeg, Manitoba Copyright © 2010 by Lauren Chochinov Library and Archives Bibliothèque et Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de l’édition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre référence ISBN: 978-0-494-70110-2 Our file Notre référence ISBN: 978-0-494-70110-2 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non- L’auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library and permettant à la Bibliothèque et Archives Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par télécommunication ou par l’Internet, prêter, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des thèses partout dans le loan, distribute and sell theses monde, à des fins commerciales ou autres, sur worldwide, for commercial or non- support microforme, papier, électronique et/ou commercial purposes, in microform, autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L’auteur conserve la propriété du droit d’auteur ownership and moral rights in this et des droits moraux qui protège cette thèse. Ni thesis. Neither the thesis nor la thèse ni des extraits substantiels de celle-ci substantial extracts from it may be ne doivent être imprimés ou autrement printed or otherwise reproduced reproduits sans son autorisation. -

Monty Python's SPAMALOT

Monty Python’s Spamalot CHARACTERS Please note that the ages listed just serve as a guide. All roles are available and casting is open, and newcomers are welcome and encouraged. Also, character doublings are only suggested here and may be changed based on audition results and production needs. KING ARTHUR (Baritone, Late 30s-60s) – The King of England, who sets out on a quest to form the Knights of the Round Table and find the Holy Grail. Great humor. Good singer. THE LADY OF THE LAKE (Alto with large range, 20s-40s) – A Diva. Strong, beautiful, possesses mystical powers. The leading lady of the show. Great singing voice is essential, as she must be able to sing effortlessly in many styles and vocal registers. Sings everything from opera to pop to scatting. Gets angry easily. SIR ROBIN (Tenor/Baritone, 30s-40s) – A Knight of the Round Table. Ironically called "Sir Robin the Brave," though he couldn't be more cowardly. Joins the Knights for the singing and dancing. Also plays GUARD 1 and BROTHER MAYNARD, a long-winded monk. A good mover. SIR LANCELOT (Tenor/Baritone, 30s-40s) – A Knight of the Round Table. He is fearless to a bloody fault but through a twist of fate discovers his "softer side." This actor MUST be great with character voices and accents, as he also plays THE FRENCH TAUNTER, an arrogant, condescending, over-the-top Frenchman; the KNIGHT OF NI, an absurd, cartoonish leader of a peculiar group of Knights; and TIM THE ENCHANTER, a ghostly being with a Scottish accent. -

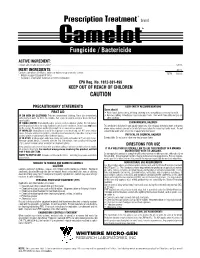

Camelot* Fungicide / Bactericide

® Prescription Treatment brand Camelot* Fungicide / Bactericide ACTIVE INGREDIENT: Copper salts of fatty and rosin acids† . 58.0% INERT INGREDIENTS: . 42.0% Contains petroleum distillates, xylene or xylene range aromatic solvent. TOTAL 100.0% † Metallic Copper Equivalent 5.14%) * Camelot is a registered Trademark of Griffin Corporation. EPA Reg. No. 1812-381-499 KEEP OUT OF REACH OF CHILDREN CAUTION PRECAUTIONARY STATEMENTS USER SAFETY RECOMMENDATIONS Users should: FIRST AID • Wash hands before eating, drinking, chewing gum, using tobacco or using the toilet. IF ON SKIN OR CLOTHING: Take off contaminated clothing. Rinse skin immediately • Remove clothing immediately if pesticide gets inside. Then wash thoroughly and put on with plenty of water for 15 to 20 minutes. Call a poison control center or doctor for treat- clean clothing. ment advice. IF SWALLOWED: Immediately call a poison control center or doctor. Do not induce ENVIRONMENTAL HAZARDS vomiting unless told to do so by a poison control center or doctor. Do not give any liquid This pesticide is toxic to fish and aquatic organisms. Do not apply directly to water, or to areas to the person. Do not give anything by mouth to an unconscious person. where surface water is present or to intertidal areas below the mean high water mark. Do not IF INHALED: Move person to fresh air. If person is not breathing, call 911 or an ambu- contaminate water when disposing of equipment washwaters. lance, then give artificial respiration, preferably mouth-to-mouth, if possible. Call a poison control center or doctor for further treatment advice. PHYSICAL OR CHEMICAL HAZARDS IF IN EYES: Hold eye open and rinse slowly and gently with water for 15 to 20 minutes. -

The Duke: Arthurian Legends Expansion Pack

™ Arthurian Legends Expansion Pack The politics of the high courts are elegant, shadowy, and subtle. Fort Tile: Players can use the Fort Tile as shown on pages 7-8 of Not so in the outlying duchies. Rival dukes contend for unclaimed the rulebook for any game with these tiles. However, they can also lands far from the king’s reach, and possession is the law in these play with the reverse side of the Fort, Camelot. Camelot is an Ex- lands. Use your forces to adapt to your opponent’s strategies, cap- panded Play tile (see p. 6 of the rulebook) and so both players should turing enemy troops, before you lose your opportunity to seize these agree to its use before play begins. lands for your good. Randomly place Camelot in any square in one of the two middle In The Duke, players move their troops (tiles) around the board rows of the board. and flip them over after each move. Each tile’s side shows a different For the Arthur player, if one of his Arthurian Legends’ tiles is in- movement pattern. If you end your movement in a square occupied side Camelot (King Arthur, Lancelot, Guinevere, Percival, or Merlin), by an opponent’s tile, you capture that tile. Capture your opponent’s then the Camelot Tile gains Command ability in all eight squares Duke to win! surrounding Camelot. On his turn, any time those conditions are met, the player may use the Command ability of Camelot; the Troop ARTHurIan leGenDS EXPanSIon PacK RULES Tile on Camelot does not flip, but the Camelot Tile DOES flip over to Arthur, Guineviere, Merlin, Lancelot and Perceval replace the light the Fort side; as long as it’s on the Fort side, the Command ability no stained Duke, Duchess, Wizard, Champion and Assassin Tiles.