LPSC 41-M3 Orientale-Volcanic Vents-Final(O)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

TRANSIENT LUNAR PHENOMENA: REGULARITY and REALITY Arlin P

The Astrophysical Journal, 697:1–15, 2009 May 20 doi:10.1088/0004-637X/697/1/1 C 2009. The American Astronomical Society. All rights reserved. Printed in the U.S.A. TRANSIENT LUNAR PHENOMENA: REGULARITY AND REALITY Arlin P. S. Crotts Department of Astronomy, Columbia University, Columbia Astrophysics Laboratory, 550 West 120th Street, New York, NY 10027, USA Received 2007 June 27; accepted 2009 February 20; published 2009 April 30 ABSTRACT Transient lunar phenomena (TLPs) have been reported for centuries, but their nature is largely unsettled, and even their existence as a coherent phenomenon is controversial. Nonetheless, TLP data show regularities in the observations; a key question is whether this structure is imposed by processes tied to the lunar surface, or by terrestrial atmospheric or human observer effects. I interrogate an extensive catalog of TLPs to gauge how human factors determine the distribution of TLP reports. The sample is grouped according to variables which should produce differing results if determining factors involve humans, and not reflecting phenomena tied to the lunar surface. Features dependent on human factors can then be excluded. Regardless of how the sample is split, the results are similar: ∼50% of reports originate from near Aristarchus, ∼16% from Plato, ∼6% from recent, major impacts (Copernicus, Kepler, Tycho, and Aristarchus), plus several at Grimaldi. Mare Crisium produces a robust signal in some cases (however, Crisium is too large for a “feature” as defined). TLP count consistency for these features indicates that ∼80% of these may be real. Some commonly reported sites disappear from the robust averages, including Alphonsus, Ross D, and Gassendi. -

Special Catalogue Milestones of Lunar Mapping and Photography Four Centuries of Selenography on the Occasion of the 50Th Anniversary of Apollo 11 Moon Landing

Special Catalogue Milestones of Lunar Mapping and Photography Four Centuries of Selenography On the occasion of the 50th anniversary of Apollo 11 moon landing Please note: A specific item in this catalogue may be sold or is on hold if the provided link to our online inventory (by clicking on the blue-highlighted author name) doesn't work! Milestones of Science Books phone +49 (0) 177 – 2 41 0006 www.milestone-books.de [email protected] Member of ILAB and VDA Catalogue 07-2019 Copyright © 2019 Milestones of Science Books. All rights reserved Page 2 of 71 Authors in Chronological Order Author Year No. Author Year No. BIRT, William 1869 7 SCHEINER, Christoph 1614 72 PROCTOR, Richard 1873 66 WILKINS, John 1640 87 NASMYTH, James 1874 58, 59, 60, 61 SCHYRLEUS DE RHEITA, Anton 1645 77 NEISON, Edmund 1876 62, 63 HEVELIUS, Johannes 1647 29 LOHRMANN, Wilhelm 1878 42, 43, 44 RICCIOLI, Giambattista 1651 67 SCHMIDT, Johann 1878 75 GALILEI, Galileo 1653 22 WEINEK, Ladislaus 1885 84 KIRCHER, Athanasius 1660 31 PRINZ, Wilhelm 1894 65 CHERUBIN D'ORLEANS, Capuchin 1671 8 ELGER, Thomas Gwyn 1895 15 EIMMART, Georg Christoph 1696 14 FAUTH, Philipp 1895 17 KEILL, John 1718 30 KRIEGER, Johann 1898 33 BIANCHINI, Francesco 1728 6 LOEWY, Maurice 1899 39, 40 DOPPELMAYR, Johann Gabriel 1730 11 FRANZ, Julius Heinrich 1901 21 MAUPERTUIS, Pierre Louis 1741 50 PICKERING, William 1904 64 WOLFF, Christian von 1747 88 FAUTH, Philipp 1907 18 CLAIRAUT, Alexis-Claude 1765 9 GOODACRE, Walter 1910 23 MAYER, Johann Tobias 1770 51 KRIEGER, Johann 1912 34 SAVOY, Gaspare 1770 71 LE MORVAN, Charles 1914 37 EULER, Leonhard 1772 16 WEGENER, Alfred 1921 83 MAYER, Johann Tobias 1775 52 GOODACRE, Walter 1931 24 SCHRÖTER, Johann Hieronymus 1791 76 FAUTH, Philipp 1932 19 GRUITHUISEN, Franz von Paula 1825 25 WILKINS, Hugh Percy 1937 86 LOHRMANN, Wilhelm Gotthelf 1824 41 USSR ACADEMY 1959 1 BEER, Wilhelm 1834 4 ARTHUR, David 1960 3 BEER, Wilhelm 1837 5 HACKMAN, Robert 1960 27 MÄDLER, Johann Heinrich 1837 49 KUIPER Gerard P. -

Table of Exposures

Table of Exposures Dole UT Focal Emulsion Exposure Moon's age Plate Nos. ralio sec. days 08.11.65 2132· f/29 Kodak 0.250 Plole 0.4 15.3 7e/2 08.01.66 2228 f/24 Kodak 0.250 Plate 0.31 17.0 3b, 15e 31.01.66 1947 1/24 Kodak 0.250 Plale 0.3 10.1 5b 02.02.66 1944 f/24 Kodak 0.250 Plote 0.25 12.1 7b, 8b 06.02.66 2326 1/24 Kodak 0.250 Plole 0.2 16.3 14c,16b 05.03.66 2259 1/41 IIford Zenith Plole 0.1 13 .5 lOe/l 27.04.66 2152 1/24 lIford G.30 Plate 0.5 6.9 150 28.04.66 2046 f/30 lIford G.30 Pia Ie 0.8 7.9 10,130 23.05.66 2033 f/24 Kodak 0.250 Plole 0.7 3.4 15e/2 23.05,66 2034 f/24 Kodak 0.250 Plate 0.7 3.4 3e/2,4b 23.05.66 2036 1/24 Kodak 0.250 Plate 0.7 3.4 16e 28.05.66 2122 1/30 IIford G.30 Plole 0.8 8.4 140 29.05.66 2103 1/30 IIford G.30 Plate 0.8 9.4 2e 23.06.66 2109 f/24 lIford G.30 Pia Ie 1.0 5.0 160 06.08.66 0211 f/30 Illord G.30 Pia Ie 0.7 18.9 2b 06.08.66 0215 1/30 IIford G.30 Plale 0.7 18.9 lb, 13b 09.08.66 0315 1/30 IIlord G.30 Plate 1.1 23.8 50,60 09.08.66 03 17 1/30 Ilford G.30 Plate 1.1 23.8 90, 91/2, 11 b, 12e/l 06. -

Highresolution Local Gravity Model of the South Pole of the Moon From

GeophysicalResearchLetters RESEARCH LETTER High-resolution local gravity model of the south pole 10.1002/2014GL060178 of the Moon from GRAIL extended mission data 1,2 2 2,3 2 Key Points: Sander Goossens , Terence J. Sabaka , Joseph B. Nicholas , Frank G. Lemoine , • We present a high-resolution gravity David D. Rowlands2, Erwan Mazarico2,4, Gregory A. Neumann2, model of the south pole of the Moon David E. Smith4, and Maria T. Zuber4 • Improved correlations with topography to higher degrees than 1CRESST, University of Maryland Baltimore County, Baltimore, Maryland, USA, 2NASA Goddard Space Flight Center, global models 3 4 • Improved fits to the data and Greenbelt, Maryland, USA, Emergent Space Technologies, Greenbelt, Maryland, USA, Department of Earth, Atmospheric reduced striping that is present in and Planetary Sciences, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, Massachusetts, USA global models Abstract We estimated a high-resolution local gravity field model over the south pole of the Moon Supporting Information: using data from the Gravity Recovery and Interior Laboratory’s extended mission. Our solution consists of • Readme • Figures S1 adjustments with respect to a global model expressed in spherical harmonics. The adjustments are • Figures S2 expressed as gridded gravity anomalies with a resolution of 1/6◦ by 1/6◦ (equivalent to that of a degree • Figures S3 and order 1080 model in spherical harmonics), covering a cap over the south pole with a radius of 40◦.The • Figures S4 • Figures S5 gravity anomalies have been estimated from a short-arc analysis using only Ka-band range-rate (KBRR) • Figures S6 data over the area of interest. -

10Great Features for Moon Watchers

Sinus Aestuum is a lava pond hemming the Imbrium debris. Mare Orientale is another of the Moon’s large impact basins, Beginning observing On its eastern edge, dark volcanic material erupted explosively and possibly the youngest. Lunar scientists think it formed 170 along a rille. Although this region at first appears featureless, million years after Mare Imbrium. And although “Mare Orien- observe it at several different lunar phases and you’ll see the tale” translates to “Eastern Sea,” in 1961, the International dark area grow more apparent as the Sun climbs higher. Astronomical Union changed the way astronomers denote great features for Occupying a region below and a bit left of the Moon’s dead lunar directions. The result is that Mare Orientale now sits on center, Mare Nubium lies far from many lunar showpiece sites. the Moon’s western limb. From Earth we never see most of it. Look for it as the dark region above magnificent Tycho Crater. When you observe the Cauchy Domes, you’ll be looking at Yet this small region, where lava plains meet highlands, con- shield volcanoes that erupted from lunar vents. The lava cooled Moon watchers tains a variety of interesting geologic features — impact craters, slowly, so it had a chance to spread and form gentle slopes. 10Our natural satellite offers plenty of targets you can spot through any size telescope. lava-flooded plains, tectonic faulting, and debris from distant In a geologic sense, our Moon is now quiet. The only events by Michael E. Bakich impacts — that are great for telescopic exploring. -

Composition of the Deposits of the Lunar Orientale Basin P.D. Spudis1 and D.J.P

45th Lunar and Planetary Science Conference (2014) 1469.pdf Composition of the Deposits of the Lunar Orientale Basin P.D. Spudis1 and D.J.P. Martin2 1. Lunar and Plane- tary Institute, Houston TX 77058 [email protected] 2. School of Earth, Atmospheric and Environmental Sci- ences, University of Manchester, Oxford Road, Manchester, United Kingdom, M13 9PL Introduction. Orientale is the youngest and best- must constitute some fraction of the subsurface materi- preserved multi-ring impact basin on the Moon and has als of the inner basin as their presence is evident as a long been studied for clues to the processes and histo- mixing component in the ejecta of Maunder crater, the ries of older, more degraded features [1-4]. We have largest post-basin impact crater within Orientale. recently completed a new geological map derived from These basalts probably make up feeder dikes and vent LRO image and topographic data that show the distri- deposits associated with the emplacement of Mare bution and relations of the geological units of the basin Orientale. The other significant departure from the [5]. Using this new map as template, we can isolate feldspathic highlands composition comes in the form individual basin units and study their composition to of numerous basin ring massifs that appear to be com- the exclusion of adjacent and overlying units [6]. Us- posed of pure anorthosite [9, 10]. Anorthosite massifs ing this approach, we have studied the impact melt are most abundant in the Inner Rook ring, suggesting sheet of the Orientale basin and concluded that it has the presence of a regionally contiguous sub-layer of not been differentiated [6] as had been proposed [7]. -

Water on the Moon, III. Volatiles & Activity

Water on The Moon, III. Volatiles & Activity Arlin Crotts (Columbia University) For centuries some scientists have argued that there is activity on the Moon (or water, as recounted in Parts I & II), while others have thought the Moon is simply a dead, inactive world. [1] The question comes in several forms: is there a detectable atmosphere? Does the surface of the Moon change? What causes interior seismic activity? From a more modern viewpoint, we now know that as much carbon monoxide as water was excavated during the LCROSS impact, as detailed in Part I, and a comparable amount of other volatiles were found. At one time the Moon outgassed prodigious amounts of water and hydrogen in volcanic fire fountains, but released similar amounts of volatile sulfur (or SO2), and presumably large amounts of carbon dioxide or monoxide, if theory is to be believed. So water on the Moon is associated with other gases. Astronomers have agreed for centuries that there is no firm evidence for “weather” on the Moon visible from Earth, and little evidence of thick atmosphere. [2] How would one detect the Moon’s atmosphere from Earth? An obvious means is atmospheric refraction. As you watch the Sun set, its image is displaced by Earth’s atmospheric refraction at the horizon from the position it would have if there were no atmosphere, by roughly 0.6 degree (a bit more than the Sun’s angular diameter). On the Moon, any atmosphere would cause an analogous effect for a star passing behind the Moon during an occultation (multiplied by two since the light travels both into and out of the lunar atmosphere). -

PROJECT PENGUIN Robotic Lunar Crater Resource Prospecting VIRGINIA POLYTECHNIC INSTITUTE & STATE UNIVERSITY Kevin T

PROJECT PENGUIN Robotic Lunar Crater Resource Prospecting VIRGINIA POLYTECHNIC INSTITUTE & STATE UNIVERSITY Kevin T. Crofton Department of Aerospace & Ocean Engineering TEAM LEAD Allison Quinn STUDENT MEMBERS Ethan LeBoeuf Brian McLemore Peter Bradley Smith Amanda Swanson Michael Valosin III Vidya Vishwanathan FACULTY SUPERVISOR AIAA 2018 Undergraduate Spacecraft Design Dr. Kevin Shinpaugh Competition Submission i AIAA Member Numbers and Signatures Ethan LeBoeuf Brian McLemore Member Number: 918782 Member Number: 908372 Allison Quinn Peter Bradley Smith Member Number: 920552 Member Number: 530342 Amanda Swanson Michael Valosin III Member Number: 920793 Member Number: 908465 Vidya Vishwanathan Dr. Kevin Shinpaugh Member Number: 608701 Member Number: 25807 ii Table of Contents List of Figures ................................................................................................................................................................ v List of Tables ................................................................................................................................................................vi List of Symbols ........................................................................................................................................................... vii I. Team Structure ........................................................................................................................................................... 1 II. Introduction .............................................................................................................................................................. -

Glossary of Lunar Terminology

Glossary of Lunar Terminology albedo A measure of the reflectivity of the Moon's gabbro A coarse crystalline rock, often found in the visible surface. The Moon's albedo averages 0.07, which lunar highlands, containing plagioclase and pyroxene. means that its surface reflects, on average, 7% of the Anorthositic gabbros contain 65-78% calcium feldspar. light falling on it. gardening The process by which the Moon's surface is anorthosite A coarse-grained rock, largely composed of mixed with deeper layers, mainly as a result of meteor calcium feldspar, common on the Moon. itic bombardment. basalt A type of fine-grained volcanic rock containing ghost crater (ruined crater) The faint outline that remains the minerals pyroxene and plagioclase (calcium of a lunar crater that has been largely erased by some feldspar). Mare basalts are rich in iron and titanium, later action, usually lava flooding. while highland basalts are high in aluminum. glacis A gently sloping bank; an old term for the outer breccia A rock composed of a matrix oflarger, angular slope of a crater's walls. stony fragments and a finer, binding component. graben A sunken area between faults. caldera A type of volcanic crater formed primarily by a highlands The Moon's lighter-colored regions, which sinking of its floor rather than by the ejection of lava. are higher than their surroundings and thus not central peak A mountainous landform at or near the covered by dark lavas. Most highland features are the center of certain lunar craters, possibly formed by an rims or central peaks of impact sites. -

Similarity Laws of Lunar and Terrestrial Volcanic Flows*

General Disclaimer One or more of the Following Statements may affect this Document This document has been reproduced from the best copy furnished by the organizational source. It is being released in the interest of making available as much information as possible. This document may contain data, which exceeds the sheet parameters. It was furnished in this condition by the organizational source and is the best copy available. This document may contain tone-on-tone or color graphs, charts and/or pictures, which have been reproduced in black and white. This document is paginated as submitted by the original source. Portions of this document are not fully legible due to the historical nature of some of the material. However, it is the best reproduction available from the original submission. Produced by the NASA Center for Aerospace Information (CASI) SIMILARITY LAWS OF LUNAR AND TERRESTRIAL VOLCANIC FLOWS* S. I. Pai and Y. Hsu Institute for Physical Science and Technology and Aerospace Engineering Department, University of Maryland, College Park Maryland 20742, and ^g15Z021.^,, ^.^,121319 7 ^t , John A. O'Keefe Goddard Space Flight Center, Greenbelt, Maryland 204T° JUN 1977 LP '' RECEIVED ^n NASA STI FACILITY INPUT BRANCH \c. STRACT Alt! ; \Z 1Z A mathematical model for the volcanic flow in planets is proposed.^^ This mathematical model, which is one-dimensional, steady duct flow of a mixture of a gas and small solid particles ( rock), has been analyzed. We v+ 0 apply this model to the lunar and the terrestrial volcanic flows under geo- +oN m U co metrically and dynamically similar conditions. -

INTERAGENCY REPORT: ASTROGEOLOGY 7 ADVANCED SYSTEMS TRAVERSE RESEARCH PROJECT REPORT by G

INTERAGENCY REPORT: ASTROGEOLOGY 7 ADVANCED SYSTEMS TRAVERSE RESEARCH PROJECT REPORT By G. E. Ulrich With a Section on Problems for Geologic Investigations of the Orientale Region of the Moon By R. S. Saunders July 1968 CONTENTS Page Abs tract . ............. 1 Introduct ion . •• # • ••• ••• .' • 2 Physiographic subdivision of the lunar surface 3 Site selection and preliminary traverse research. 8 Lunar topographic data •••••••.•.•••••• 17 Objectives and evaluation of traverse concepts • 20 Recommendations for continued traverse research .••• 26 Problems for geologic investigations of the Orientale region of the Moon, by R. S. Saunders 30 Introduct ion •.•• •••. 30 Physiography 30 Pre-Orbiter observations and i~terpretations 35 Geologic interpretations based on Orbiter photography ••••••••• 38 Conelusions •••• .•••. 54 References 56 ILLUSTRATIONS Figure 1. Map and index to photographs of Orientale basin region ••••.•••••• 4 2. Crater-size frequency distributions of Orientale basin terrain units •••••• 11 3. Orientale basin region showing pre- liminary traverse evaluation areas ••••• 14 4. Effect of photographic exposure on shadow measurements 15 5. Alternate traverse areas for short and intermediate duration missions. North eastern sector of central Orientale basin ................... 24 6. Preliminary photogeologic map of the Orientale basin region. .•• .. .. 32 iii Page Figure 7. Sketch map of Mare Orientale region prepared from Earth-based telescopic photography • 36 8-21. Orbiter IV photographs of Orientale basin region showing-- . 8. Part of wr{nk1e ridge . 41 9. Slump scarps around steptoe and collapse depression . 44 10. Slump scarps along margin of central mare basin outlining collapse depression • • . • 44 11. Possible caldera 45 12. Northeast quadrant of inner ring showing central basin material and mare units 45 13. -

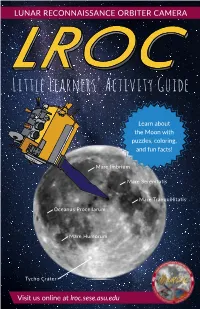

Little Learners' Activity Guide

LUNAR RECONNAISSANCE ORBITER CAMERA Little Learners’ Activity Guide Learn about the Moon with puzzles, coloring, and fun facts! Mare Imbrium Mare Serenitatis Mare Tranquillitatis Oceanus Procellarum Mare Humorum Tycho Crater Visit us online at lroc.sese.asu.edu Online resources Additional information and content, including supplemental learning activities, can be accessed at the following online locations: 1. Little Learners’ Activity Guide: lroc.sese.asu.edu/littlelearners 2. LROC website: lroc.sese.asu.edu 3. Resources for teachers: lroc.sese.asu.edu/teach 4. Learn about the Moon’s history: lroc.sese.asu.edu/learn 5. LROC Lunar Quickmap 3D: quickmap.lroc.asu.edu Copyright 2018, Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter Camera i Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter Camera Fun Facts for Beginners • The Moon is 363,301 kilometers (225,745 miles) from the Earth. • The surface area of the Moon is almost as large as the continent of Africa. • It takes 27 days for the Moon to orbit around the Earth. • The farside is the side of the Moon we cannot see from Earth. • South Pole Aitken is the largest impact basin on the lunar farside. • Impact basins are formed as the result of impacts from asteroids or comets and are larger than craters. • Regolith is a layer of loose dust, dirt, soil, and broken rock deposits that cover solid rock. • The two main types of rock that make up the Moon’s crust are anorthosite and basalt. • A person weighing 120 lbs on Earth weighs 20 lbs on the Moon because gravity on the Moon is 1/6 as strong as on Earth.