Full Text in Pdf Format

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Oil, Gas & Energy Sector

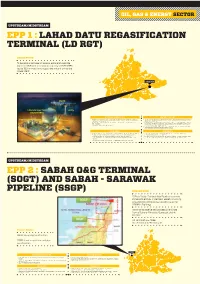

OIL, GAS & ENERGY SECTOR UPSTREAM/MIDSTREAM EPP 1 : LAHAD DATU REGASIFICATION TERMINAL (LD RGT) DESCRIPTION To develop a facilities to receive, store and vaporize imported LNG with a maximum capacity of 0.76 MTPA (up to 100 mmscfd) and supply the natural gas to the Power Plant lahad datu Berth LNG Storage Tank Jetty (0.76 MTPA) Key outcomes of the EPP / KPIs What needs to be done? Vaporization Station • Availability of natural gas supply at east coast of Sabah including Sandakan, Lahad Datu • Construction period of LNG Storage Tank which is the critical path of the project (normally and Tawau (also along the route) will take up to 24 months) • Transfer of technology and knowledge to local manpower and contractors who are involved • Front End phase of a project, where activities are mainly focused towards project planning with this project and contracting/bidding activities for the appointment of Frond End Engineering Design • Spurring the economy along the pipeline Consultant expected in mid-October 2011 • Evaluate and finalize the land lease of the reclaimed land of the proposed site with POIC. • Site Reclamation works is expected to start by Q1 2012 Key Challenges Mitigation Plan • Transporting major equipment and bulk materials from Sandakan to Lahad Datu (~200km) • Improvement of the road condition from Sandakan to Lahad Datu or consider for • Shortage of capable manpower due to simultaneous construction of LD power plant permanent/temporary jetty at Lahad Datu • Available manpower are lack of re-gas terminal construction skills (special) -

Conserving the Vulnerable Dugong Dugong Dugon in the Sulu Sea, Malaysia

Short Communication Using community knowledge in data-deficient regions: conserving the Vulnerable dugong Dugong dugon in the Sulu Sea, Malaysia L EELA R AJAMANI Abstract Community knowledge of the status, threats and the dugong Dugong dugon, a rare species of marine mammal conservation issues affecting the dugong Dugong dugon was that is categorized as Vulnerable on the IUCN Red List investigated in the Sulu Sea, Malaysia. Interviews with local (Marsh, 2008). In Malaysia the dugong is protected by the fishermen were conducted in 12 villages from the tip of Wildlife Conservation Enactment 1997 (Sabah) and Tanjung Inaruntung to Jambongan Island, in northern Fisheries Act 1985, which includes the Federal Territories Sabah, Malaysia. According to the respondents dugong and the Exclusive Economic Zone. numbers are low and sightings are rare. Dugongs have been There has been limited research on this mammal on sighted around Jambongan, Tigabu, Mandidarah and the Malaysian side of the Sulu Sea, which is also part of Malawali Islands. The apparent decline of the dugong in the biodiverse Coral Triangle. Dugongs have been sighted this area is possibly because of incidental entanglement in at Banggi, Balambangan and Jambongan Islands, and nets, and opportunistic hunting. Seagrasses are present and Sandakan (Dolar et al., 1997; Jaaman & Lah-Anyi, 2003; have economic importance to the community. The fisher- Rajamani & Marsh, 2010). There have been incidences of men have difficulty in understanding issues of conservation dugongs harvested in Tambisan, in Sandakan district, and in relation to dugongs. I recommend that conservation init- sold in the Sandakan market (Dolar et al., 1997). It is iatives begin with dialogue and an education programme, generally believed that dugong numbers are low in East followed by incentives for development of alternative liveli- Malaysia (Jaaman & Lah-Anyi, 2003; Rajamani & Marsh, hoods. -

Sabah REDD+ Roadmap Is a Guidance to Press Forward the REDD+ Implementation in the State, in Line with the National Development

Study on Economics of River Basin Management for Sustainable Development on Biodiversity and Ecosystems Conservation in Sabah (SDBEC) Final Report Contents P The roject for Develop for roject Chapter 1 Introduction ............................................................................................................. 1 1.1 Background of the Study .............................................................................................. 1 1.2 Objectives of the Study ................................................................................................ 1 1.3 Detailed Work Plan ...................................................................................................... 1 ing 1.4 Implementation Schedule ............................................................................................. 3 Inclusive 1.5 Expected Outputs ......................................................................................................... 4 Government for for Government Chapter 2 Rural Development and poverty in Sabah ........................................................... 5 2.1 Poverty in Sabah and Malaysia .................................................................................... 5 2.2 Policy and Institution for Rural Development and Poverty Eradication in Sabah ............................................................................................................................ 7 2.3 Issues in the Rural Development and Poverty Alleviation from Perspective of Bangladesh in Corporation City Biodiversity -

Plate Tectonics and Seismic Activities in Sabah Area

Plate Tectonics and Seismic Activities in Sabah Area Kuei-hsiang CHENG* Kao Yuan University, 1821 Zhongshan Road, Luzhu District, Kaohsiung, Taiwan. *Corresponding author: [email protected]; Tel: 886-7-6077750; Fax: 886-7-6077762 A b s t r a c t Received: 27 November 2015 Ever since the Pliocene which was 1.6 million years ago, the structural Revised: 25 December 2015 geology of Sabah is already formed; it is mainly influenced by the early Accepted: 7 January 2016 South China Sea Plate, which is subducted into the Sunda Plate. However, In press: 8 January 2016 since the Cenozoic, the Sunda Plate is mainly influenced by the western and Online: 1 April 2016 southern of the Sunda-Java Arc and Trench system, and the eastern side of Luzon Arc and Trench system which has an overall impact on the tectonic Keywords: and seismic activity of Sunda plate. Despite the increasing tectonic activities Arc and Trench System, of Sunda-Java Arc and Trench System, and of Luzon Arc and Trench Tectonic earthquake, Seismic System since the Quaternary, which cause many large and frequent zoning, GM(1,1)model, earthquakes. One particular big earthquake is the M9.0 one in Indian Ocean Seismic potential assessment in 2004, leading to more than two hundred and ninety thousand deaths or missing by the tsunami caused by the earthquake. As for Borneo island which is located in residual arc, the impact of tectonic earthquake is trivial; on the other hand, the Celebes Sea which belongs to the back-arc basin is influenced by the collision of small plates, North Sulawesi, which leads to two M≧7 earthquakes (1996 M7.9 and 1999 M7.1) in the 20th century. -

“Fractured Basement” Play in the Sabah Basin? – the Crocker and Kudat Formations As Hydrocarbon Reservoirs and Their Risk Factors Mazlan Madon1,*, Franz L

Bulletin of the Geological Society of Malaysia, Volume 69, May 2020, pp. 157 - 171 DOI: https://doi.org/10.7186/bgsm69202014 “Fractured basement” play in the Sabah Basin? – the Crocker and Kudat formations as hydrocarbon reservoirs and their risk factors Mazlan Madon1,*, Franz L. Kessler2, John Jong3, Mohd Khairil Azrafy Amin4 1 Advisor, Malaysian Continental Shelf Project, National Security Council, Malaysia 2 Goldbach Geoconsultants O&G and Lithium Exploration, Germany 3 A26-05, One Residences, 6 Jalan Satu, Chan Sow Lin, KL, Malaysia 4 Malaysia Petroleum Management, PETRONAS, Malaysia * Corresponding author email address: [email protected] Abstract: Exploration activities in the Sabah Basin, offshore western Sabah, had increased tremendously since the discovery of oil and gas fields in the deepwater area during the early 2000s. However, the discovery rates in the shelfal area have decreased over the years, indicating that the Inboard Belt of the Sabah Basin may be approaching exploration maturity. Thus, investigation of new play concepts is needed to spur new exploration activity on the Sabah shelf. The sedimentary formations below the Deep Regional Unconformity in the Sabah Basin are generally considered part of the economic basement which is seismically opaque in seismic sections. Stratigraphically, they are assigned to the offshore Sabah “Stages” I, II, and III which are believed to be the lateral equivalents of the pre-Middle Miocene clastic formations outcropping in western Sabah, such as the Crocker and Kudat formations and some surface hydrocarbon seeps have been reported from Klias and Kudat peninsulas. A number of wells in the inboard area have found hydrocarbons, indicating that these rocks are viable drilling targets if the charge and trapping mechanisms are properly understood. -

Concern of Veterinary Authorities with Respect to Borders Crossing

Concern of Veterinary Authorities With Respect to Borders Crossing NURUL HUSNA ZULKIFLI DEPARTMENT OF VETERINARY SERVICES MALAYSIA 19 FEBRUARY 2019 DEPARTMENT OF VETERINARY SERVICES MALAYSIA 01 Overview Under the Ministry of Agriculture and Agro-Based Industries (MOA) Malaysia 02 Responsibility Veterinary competent authority of Malaysia 03 Scope Responsible in performing risk analysis as well as development of import requirements and for issuance of veterinary health certificate (as stated under the Provisions of Animals Act 1953, Section 16. DEPARTMENT OF QUARANTINE & INSPECTION SERVICES MALAYSIA (MAQIS) 01 Overview Under the Ministry of Agriculture and Agro-Based Industries (MOA) Malaysia 02 Responsibility One stop centre for quarantine and inspection services 03 Scope Responsible in the enforcement of written laws at entry point, quarantine stations and quarantine premises as well as in the issuance of permits, licenses and certificates of import and export DVS as a competent authority responsible in the approval of animal and animal products movement STATE DVS IN MALAYSIA 1. Perlis 2. Kedah 3. Pulau Pinang 4. Kelantan 5. Terengganu 6. Perak 7. Pahang 8. Selangor 9. Putrajaya (Headquarters) 10. Negeri Sembilan 11. Melaka 12. Johor 13. Labuan MAQIS as main agency responsible in quarantine, inspection and enforcement STATE MAQIS IN MALAYSIA 1. Selangor/Negeri Sembilan 2. Johor/Melaka 3. Pulau Pinang 4. Kedah 5. Kelantan 6. Perlis 7. Perak 8. Labuan 9. Pahang/Terengganu MAQIS Quarantine Station Labuan KLIA • KLIA Quarantine Station • Padang -

Prk Kerusi Parlimen Pasca Pru-14 Di Sabah: P186- Sandakan, P176-Kimanis, P185-Batu Sapi Dan Darurat

Volume 6 Issue 23 (April 2021) PP. 200-214 DOI 10.35631/IJLGC.6230014 INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF LAW, GOVERNMENT AND COMMUNICATION (IJLGC) www.ijlgc.com PRK KERUSI PARLIMEN PASCA PRU-14 DI SABAH: P186- SANDAKAN, P176-KIMANIS, P185-BATU SAPI DAN DARURAT THE POST GE-14 PARLIAMENTARY SEAT BY-ELECTIONS IN SABAH: P186- SANDAKAN, P176-KIMANIS, P185-BATU SAPI AND THE EMERGENCY Mohd Azri Ibrahim1*, Romzi Ationg2*, Mohd Sohaimi Esa3*, Irma Wani Othman4*, Saifulazry Mokhtar5 & Abang Mohd Razif Abang Muis6 1 Centre for the Promotion of Knowledge and Language Learning, Universiti Malaysia Sabah Email: [email protected] 2 Centre for the Promotion of Knowledge and Language Learning, Universiti Malaysia Sabah Email: [email protected] 3 Centre for the Promotion of Knowledge and Language Learning, Universiti Malaysia Sabah Email: [email protected] 4 Centre for the Promotion of Knowledge and Language Learning, Universiti Malaysia Sabah Email: [email protected] 5 Centre for the Promotion of Knowledge and Language Learning, Universiti Malaysia Sabah Email: [email protected] 6 Centre for the Promotion of Knowledge and Language Learning, Universiti Malaysia Sabah Email: [email protected] * Corresponding Author Article Info: Abstrak: Article history: Kertas kerja ini mengetengahkan perbincangan tentang pelaksanaan mahupun Received date: 15.01.2021 penangguhan Pilihanraya Kecil (PRK) di Sabah dalam era pasca Pilihanraya Revised date: 15.02.2021 Umum ke-14 (PRU-14) dan kaitannya dengan pelaksanaan Perintah Kawalan Accepted date: 15.03.2021 Pergerakan (PKP) serta darurat. Secara khusus, kertas kerja ini Published date: 30.04.2021 membincangkan secara mendalam pelaksanaan PRK di P186 Sandakan dan To cite this document: P176 Kimanis. -

Mantle Structure and Tectonic History of SE Asia

Nature and Demise of the Proto-South China Sea ROBERT HALL, H. TIM BREITFELD SE Asia Research Group, Department of Earth Sciences, Royal Holloway University of London, Egham, Surrey, TW20 0EX, United Kingdom Abstract: The term Proto-South China Sea has been used in a number of different ways. It was originally introduced to describe oceanic crust that formerly occupied the region north of Borneo where the modern South China Sea is situated. This oceanic crust was inferred to have been Mesozoic, and to have been eliminated by subduction beneath Borneo. Subduction was interpreted to have begun in Early Cenozoic and terminated in the Miocene. Subsequently the term was also used for inferred oceanic crust, now disappeared, of quite different age, notably that interpreted to have been subducted during the Late Cretaceous below Sarawak. More recently, some authors have considered that southeast-directed subduction continued until much later in the Neogene than originally proposed, based on the supposition that the NW Borneo Trough and Palawan Trough are, or were recently, sites of subduction. Others have challenged the existence of the Proto-South China Sea completely, or suggested it was much smaller than envisaged when the term was introduced. We review the different usage of the term and the evidence for subduction, particularly under Sabah. We suggest that the term Proto-South China Sea should be used only for the slab subducted beneath Sabah and Cagayan between the Eocene and Early Miocene. Oceanic crust subducted during earlier episodes of subduction in other areas should be named differently and we use the term Paleo- Pacific Ocean for lithosphere subducted under Borneo in the Cretaceous. -

A Gravity High in Darvel Bay

Ceol. Soc. MaLaYJia, BulLetill 59, July 1996,. pp. 1lJ-122 A gravity high in Darvel Bay PATRICK J.e. RYALL! AND DWAYNE BEATTIE2 1 Department of Geology Dalhousie University Halifax, Nova Scotia Canada B3H 3J5 2Geoterrex Ltd. 2060 Walkley Road Ottawa, Ontario Canada K1 G 3P5 Abstract: A gravity survey was carried out along the coastlines of Darvel Bay and many of the islands (e.g. Sakar, Tabauwan, Silumpat) in the Bay. In addition stations were located along the road from Kunak to Lahad Datu. The resulting Bouguer anomaly map shows a broad gravity high of at least 60 mgal which strikes west northwest with its maximum on the southern coast of Pulau Sakar. The anomaly narrows and decreases where it comes ashore and may continue along the Silam-Beeston Complex. This large positive anomaly suggests that there is an extensive ultramafic body beneath Darvel Bay. The gravity anomaly can best be modelled as a 3 to 5 km thick slab of ultramafic rock under the Bay with amphibolites on its northern and southern edges dipping away from the Bay. This model is consistent with a folded structure which brings upper mantle rocks to the surface. It is unlikely that there is a significant thickness of Chert-Spilite Formation beneath Darvel Bay, although the gravity data w.ould permit a thickness of up to a few hundred metres. INTRODUCTION Hutchison (1968,1975) considers the ophiolitic rocks of Darvel Bay as part of a strongly arcuate Borneo line which runs from the Sulu Archipelago in the northeast, through Darvel Bay and northwestern The island of Borneo is located in a complex Sabah and along Palawan (Fig. -

Geological Mapping of Sabah, Malaysia, Using Airborne Gravity Survey

Downloaded from orbit.dtu.dk on: Oct 05, 2021 Geological Mapping of Sabah, Malaysia, Using Airborne Gravity Survey Fauzi Nordin, Ahmad; Jamil, Hassan; Noor Isa, Mohd; Mohamed, Azhari; Hj. Tahir, Sanudin; Musta, Baba ; Forsberg, René; Olesen, Arne Vestergaard; Nielsen, Jens Emil; Majid A. Kadir, Abd Total number of authors: 13 Published in: Borneo Science, The Journal of Science and Technology Publication date: 2016 Document Version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Link back to DTU Orbit Citation (APA): Fauzi Nordin, A., Jamil, H., Noor Isa, M., Mohamed, A., Hj. Tahir, S., Musta, B., Forsberg, R., Olesen, A. V., Nielsen, J. E., Majid A. Kadir, A., Fahmi Abd Majid, A., Talib, K., & Aman Sulaiman, S. (2016). Geological Mapping of Sabah, Malaysia, Using Airborne Gravity Survey. Borneo Science, The Journal of Science and Technology, 37(2), 14-27. General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. -

M.V. Solita's Passage Notes

M.V. SOLITA’S PASSAGE NOTES SABAH BORNEO, MALAYSIA Updated August 2014 1 CONTENTS General comments Visas 4 Access to overseas funds 4 Phone and Internet 4 Weather 5 Navigation 5 Geographical Observations 6 Flags 10 Town information Kota Kinabalu 11 Sandakan 22 Tawau 25 Kudat 27 Labuan 31 Sabah Rivers Kinabatangan 34 Klias 37 Tadian 39 Pura Pura 40 Maraup 41 Anchorages 42 2 Sabah is one of the 13 Malaysian states and with Sarawak, lies on the northern side of the island of Borneo, between the Sulu and South China Seas. Sabah and Sarawak cover the northern coast of the island. The lower two‐thirds of Borneo is Kalimantan, which belongs to Indonesia. The area has a fascinating history, and probably because it is on one of the main trade routes through South East Asia, Borneo has had many masters. Sabah and Sarawak were incorporated into the Federation of Malaysia in 1963 and Malaysia is now regarded a safe and orderly Islamic country. Sabah has a diverse ethnic population of just over 3 million people with 32 recognised ethnic groups. The largest of these is the Malays (these include the many different cultural groups that originally existed in their own homeland within Sabah), Chinese and “non‐official immigrants” (mainly Filipino and Indonesian). In recent centuries piracy was common here, but it is now generally considered relatively safe for cruising. However, the nearby islands of Southern Philippines have had some problems with militant fundamentalist Muslim groups – there have been riots and violence on Mindanao and the Tawi Tawi Islands and isolated episodes of kidnapping of people from Sabah in the past 10 years or so. -

East Malaysia Immigration Requirements and Practices

Insights from Global Mobility Malaysia: East Malaysia immigration requirements and practices January 20, 2017 In brief Immigration laws in Malaysia are governed under the Immigration Act, 1959/63 and apply to both West and East Malaysia that together form the Federation of Malaysia. Nevertheless, to protect the rights and interests of its people, the state governments in the East Malaysian states of Sabah, Sarawak, and the Federal Territory of Labuan retain a relatively higher degree of local government autonomy, resulting in the adoption of different immigration requirements and practices by the immigration authorities. The purpose of this Insight is to highlight current immigration practices in the East Malaysian states and how companies can ensure compliance and avoid unnecessary deployment delays of employees/ assignees to these states. In detail formation of Malaysia as a by the immigration department Background means of ensuring that the of the respective state. In most rights of East Malaysians are cases, an individual must not Malaysian immigration rules protected after the formation of hold more than one Malaysian differ between four territories, Malaysia. work permit issued by any namely West Malaysia, and the territory, at any one time. East Malaysian territories of With the differences in Sabah, Sarawak, and the Federal requirements, a West Malaysian Comparison of requirements Territory of Labuan. The company will need to ensure The requirements imposed by differences in the requirements that its employees, including the respective state in the East Malaysian territories Malaysian employees, who governments in the East are the result of an agreement intend to perform work in the Malaysia states, as compared to between West Malaysia and East Malaysian states, hold West Malaysia, are summarised East Malaysia during the appropriate work permits issued in the following table: www.pwc.com Insights Requirements West Sabah Sarawak Labuan (Federal Malaysia Territory) 1.