Bali Hai and Wala Island

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Vanuatu Mission, Nambatu, Vila, Vanuatu

Vanuatu Mission, Nambatu, Vila, Vanuatu. Photo courtesy of Nos Terry. Vanuatu Mission BARRY OLIVER Barry Oliver, Ph.D., retired in 2015 as president of the South Pacific Division of Seventh-day Adventists, Sydney, Australia. An Australian by birth Oliver has served the Church as a pastor, evangelist, college teacher, and administrator. In retirement, he is a conjoint associate professor at Avondale College of Higher Education. He has authored over 106 significant publications and 192 magazine articles. He is married to Julie with three adult sons and three grandchildren. The Vanuatu Mission is a growing mission in the territory of the Trans-Pacific Union Mission of the South Pacific Division. Its headquarters are in Port Vila, Vanuatu. Before independence the mission was known as the New Hebrides Mission. The Territory and Statistics of the Vanuatu Mission The territory of the Vanuatu Mission is “Vanuatu.”1 It is a part of, and reports to the Trans Pacific Union Mission which is based in Tamavua, Suva, Fiji Islands. The Trans Pacific Union comprises the Seventh-day Adventist Church entities in the countries of American Samoa, Fiji, Kiribati, Nauru, Niue, Samoa, Solomon Islands, Tokelau, Tonga, Tuvalu, and Vanuatu. The administrative office of the Vanuatu Mission is located on Maine Street, Nambatu, Vila, Vanuatu. The postal address is P.O. Box 85, Vila Vanuatu.2 Its real and intellectual property is held in trust by the Seventh-day Adventist Church (Vanuatu) Limited, an incorporated entity based at the headquarters office of the Vanuatu Mission Vila, Vanuatu. The mission operates under General Conference and South Pacific Division (SPD) operating policies. -

The Status of the Dugong (Dugon Dugon) in Vanuatu

ORIGINAL: ENGLISH SOUTH PACIFIC REGIONAL ENVIRONMENT PROGRAMME TOPIC REVIEW No. 37 THE STATUS OF THE DUGONG (DUGON DUGON) IN VANUATU M.R. Chambers, E.Bani and B.E.T. Barker-Hudson O.,;^, /ZO. ^ ll pUG-^Y^ South Pacific Commission Noumea, New Caledonia April 1989 UBHArt/ SOUTH PACIFIC COMMISSION EXECUTIVE SUMMARY This project was carried out to assess the distribution, abundance, cultural importance and threats to the dugong in Vanuatu. The study was carried out by a postal questionnaire survey and an aerial survey, commencing in October 1987. About 600 copies of the questionnaire were circulated in Vanuatu, and about 1000 kilometres of coastline surveyed from the air. Dugongs were reported or seen to occur in nearly 100 localities, including all the major islands and island groups of Vanuatu. The animals were generally reported to occur in small groups; only in three instances were groups of more than 10 animals reported. Most people reported that dugong numbers were either unchanged or were increasing. There was no evidence that dugongs migrate large distances or between islands in the archipelago, although movements may occur along the coasts of islands and between closely associated islands. Dugong hunting was reported from only a few localities, although it is caught in more areas if the chance occurs. Most hunting methods use traditional means, mainly the spear. Overall, hunting mortality is low, even in areas reported to regularly hunt dugongs. Accordingly, the dugong does not seem to be an important component of the subsistence diet in any part of Vanuatu, even though it is killed mainly for food. -

Subject/ Area: Vanuatu at the Speed We Cruise, It Will Take Us More Than

Subject/ Area: Vanuatu At the speed we cruise, it will take us more than one season to cover Vanuatu! During this past 4 months, we explored the Southern part of Vanuatu: Tanna, Aniwa, Erromango and Efate. The ultimate cruising guide for Vanuatu is the Rocket Guide (nicknamed Tusker guide, from the first sponsor - www.cruising-vanuatu.com). With charts, aerial photos and sailing directions to most anchorages, you will have no problem making landings. We also used Bob Tiews & Thalia Hearns Vanuatu cruising guide and Miz Mae’s Vanuatu guide. Those 3 reference guides and previous letters in the SSCA bulletins will help you planning a great time in Vanuatu! CM 93 electronic charts are slightly off so do not rely blindly on them! At time of writing, 100 vatu (vt) was about $1 US. Tanna: Having an official port of entry, this island was our first landfall, as cruising NW to see the Northern islands will be easier than the other way around! Port Resolution: We arrived in Port Resolution early on Lucky Thursday…lucky because that is the day of the week that the Customs and Immigration officials come the 2 1/2 hour, 4-wheel drive across from Lenakel. We checked in at no extra cost, and avoided the expense of hiring a transport (2000 vatu RT). We met Werry, the caretaker of the Port Resolution “yacht club”, donated a weary Belgian flag for his collection, and found out about the volcano visit, tours, and activities. Stanley, the son of the Chief, is responsible for relations with the yachts, and he is the tour guide or coordinator of the tours that yachties decide to do. -

Re-Membering Quirós, Bougainville and Cook in Vanuatu

Chapter 3 The Sediment of Voyages: Re-membering Quirós, Bougainville and Cook in Vanuatu Margaret Jolly Introduction: An Archipelago of Names This chapter juxtaposes the voyages of Quirós in 1606 and those eighteenth-century explorations of Bougainville and Cook in the archipelago we now call Vanuatu.1 In an early and influential work Johannes Fabian (1983) suggested that, during the period which separates these voyages, European constructions of the ªotherº underwent a profound transformation. How far do the materials of these voyages support such a view? Here I consider the traces of these journeys through the lens of this vaunted transformation and in relation to local sedimentations (and vaporisations) of memory. Vanuatu is the name of this archipelago of islands declared at independence in 1980 ± vanua ªlandº and tu ªto stand up, endure; be independentº (see figure 3.1). Both words are drawn from one of the 110 vernacular languages still spoken in the group. But, alongside this indigenous name, there are many foreign place names, the perduring traces of the movement of early European voyagers: Espiritu Santo ± the contraction of Terra Austrialia del Espiritu Santo, the name given by Quirós in 1606;2 Pentecost ± the Anglicisation of Île de Pentecôte, conferred by Bougainville, who sighted this island on Whitsunday, 22 May 1768; Malakula, Erromango and Tanna ± the contemporary spellings of the Mallicollo, Erromanga and Tanna conferred by Cook who named the archipelago the New Hebrides in 1774, a name which, for foreigners at least, lasted from that date till 1980.3 Fortunately, some of these foreign names proved more ephemeral: the island we now know as Ambae, Bougainville called Île des Lepreux (Isle of Lepers), apparently because he mistook the pandemic skin conditions of tinea imbricata or leucodermia for signs of leprosy. -

The Performance of Customary Marine Tenure in the Management of Community Fishery Resources in Melanesia

The Performance of Customary Marine Tenure in the Management of Community Fishery Resources in Melanesia VOLUME 1 Project Background & Research Methods Oakerson’s Framework for the analysis of the commons July 1999 Acknowledgements This project was funded through the UK Department for International Development (DFID) Fisheries Management Science Programme (FMSP), which is managed by MRAG Ltd. Throughout the project, MRAG enjoyed excellent collaboration with: University of the South Pacific, Marine Studies Programme Government of Vanuatu, Fisheries Department Government of Fiji, Fisheries Division (MAFF) In particular the project would like to acknowledge Professor Robin South (Marine Studies Programe, USP), Mr Moses Amos (Director, Vanuatu Fisheries Department), Mr Maciu Lagibalavu (Director, Fiji Fisheries Division), Mr Vinal Singh and Ms Nettie Moerman (Bursar’s Office, USP).The project would also like to thank Ms Doresthy Kenneth (Vanuatu Fisheries Department), Mr Francis Hickey and Mr Ralph Regenvanu (Vanuatu Cultural Centre), Mr Krishna Swamy (Fiji Fisheries Division), Mr Gene Wong (Vanuatu), Mr Felix Poni and Ms Frances Osbourne (Lautoka, Fiji), and Mr Paul Geraghty (Fijian Cultural Affairs). Last, but certainly not least, we wish to thank the field staff in Fiji and Vanuatu for their hard work and dedication. In the UK the project would like to thank colleagues at MRAG for useful advice and assistance, in particular Dr Caroline Garaway, Ms Vicki Cowan, Ms Nicola Erridge and Mr John Pearce. MRAG The Performance of Customary Marine Tenure - Volume 1 - Project Background and Research Methods Page i Table of Contents Acknowledgements ........................................................ iii List of Tables ..............................................................v List of Figures............................................................. vii 1 Project Background and Research Methods .............................. -

3. Quaternary Vertical Tectonics of the Central New Hebrides Island Arc1

Collot, J.-Y., Greene, H. G., Stokking, L. B., et al., 1992 Proceedings of the Ocean Drilling Program, Initial Reports, Vol. 134 3. QUATERNARY VERTICAL TECTONICS OF THE CENTRAL NEW HEBRIDES ISLAND ARC1 Frederick W. Taylor2 ABSTRACT Hundreds of meters of uplift of both the frontal arc and backarc characterize the late Quaternary vertical tectonic history of the central New Hebrides Island Arc. This vertical deformation is directly related to large, shallow earthquakes on the interplate thrust zone postulated on the basis of coral emergence data. This chapter presents evidence from the best documented and illustrated examples of uplifted coral reefs from the central New Hebrides Island Arc for the pattern and rates of vertical deformation caused by subduction of the d'Entrecasteaux Zone and the West Torres Massif over the past few 100 k.y. The pattern of vertical movement based on upper Quaternary coral reef terraces documents that the islands of Espiritu Santo, Malakula, Pentecost, and Maewo have risen hundreds of meters during the late Quaternary. This history suggests that the present pattern and rates of vertical deformation should be extrapolated back to at least 1 Ma, which would indicate that the total amount of structural and morphological modification of the arc during the present phase of deformation is more significant than previously assumed. The morphology of the central New Hebrides Island Arc may have resembled a more typical arc-trench area only 1-2 Ma. If the late Quaternary patterns and rates of vertical deformation have affected the central New Hebrides Island Arc since 1-2 Ma, then virtually all of the anomalous morphology that characterizes the central New Hebrides Island Arc can be attributed to the subduction of the d'Entrecasteaux Zone and the West Torres Massif. -

VANUATU \ A.A A

MAY 1999 : :w- 22257 _~~~ / Public Disclosure Authorized _. PACIFIC ISLANDS : -s,STAKEHOLDER Public Disclosure Authorized PARTICIPATION ] . ~~~-4 £\ / IN DEVELOPMENT: VANUATU \ A.A a - N ~~~DarrylTyron Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized PACIFIC ISLANDs DISCUSSION PAPER SERIES _ MBEASTASIA AND PACIFIC REGION PAPUA NEW GUINEAAND PACIFIC ISLANDS COUNTRYMANAGEMENT UNIT DISCUSSION PAPERS PRESENT RESULTS OF COUNTRYANALYSES UNDERTAKENBY THE DEPARTMENTAS PART OF ITS NORMAL WORK PROGRAM. To PRESENTTHESE RESULTS WITH THE LEAST POSSIBLE DELAY, THE TYPESCRIPTOF THIS PAPER HAS NOT BEEN PREPARED IN ACCORDANCEWITH THE PROCEDURES APPROPRIATE FOR FORMAL PRINTED TEXTS, AND THE WORLD BANK ACCEPTS NO RESPONSIBILITY FOR ERRORS. SOME SOURCES CITED IN THIS PAPER MAY BE INFORMAL DOCUMENTS THAT ARE NOT READILYAVAILABLE. THE WORLD BANK DOES NOT GUARANTEETHE ACCURACY OF THE DATA INCLUDED IN THIS PUBLICATION AND ACCEPTS NO RESPONSIBILITY FOR ANY CONSEQUENCESOF ITS USE. PACIFIC ISLANDS STAKEHOLDER PARTICIPATION IN DEVELOPMENT: VANUATU MAY, 1999 A Report for the World Bank Prepared by: Darryl Tyron Funded by the Government of Australia under the AusAID/World Bank Pacific Facility The views, interpretations and conclusions expressed in this study are the result of research supported by the World Bank, but they are entirely those of the author and should not be attributed in any manner to the World Bank, to its affiliated organisations, or to members of its Board of Executive Directors or the countries they represent. For further copies of the report, please contact: Mr. David Colbert Papua New Guinea and Pacific Islands Country Management Unit East Asia and Pacific Region The World Bank 1818 H Street, NW Washington, DC, U.S.A. -

New Larvae of Baetidae (Insecta: Ephemeroptera) from Espiritu Santo, Vanuatu

Stuttgarter Beiträge zur Naturkunde A, Neue Serie 4: 75–82; Stuttgart, 30.IV.2011. 75 New larvae of Baetidae (Insecta: Ephemeroptera) from Espiritu Santo, Vanuatu JEAN-LUC GATTOLLIAT & ARNOLD H. STANICZEK Abstract During the Global Biodiversity Survey “Santo 2006” conducted in Espiritu Santo, Vanuatu, mayfl y larvae were collected in several streams of the island. This contribution deals with the larvae of Baetidae (Insecta: Ephemerop- tera) that are represented by two species: Labiobaetis paradisus n. sp. and Cloeon sp. The presence of these two genera is not surprising as they both possess almost a worldwide distribution and constitute a great part of Austral- asian Baetidae diversity. Diagnoses of these two species are provided and their affi nities are discussed. K e y w o r d s : Australasia, Cloeon erromangense, Labiobaetis paradisus, mayfl ies, new species, Santo 2006, taxonomy. Zusammenfassung Im Rahmen der auf Espiritu Santo, Vanuatu, durchgeführten Biodiversitätserfassung “Santo 2006” wurden Eintagsfl iegenlarven in verschiedenen Fließgewässern der Insel gesammelt. Der vorliegende Beitrag behandelt die Larven der Baetidae (Insecta: Ephemeroptera), die mit zwei Arten vertreten sind: Labiobaetis paradisus n. sp. and Cloeon sp. Der Nachweis beider Gattungen ist nicht überraschend, da diese eine nahezu weltweite Verbreitung be- sitzen und einen großen Anteil der Diversität australasiatischer Baetidae ausmachen. Die beiden Arten werden be- schrieben, beziehungsweise eine Diagnose gegeben, und Unterschiede zu anderen Formen werden diskutiert. -

IHO Report on Hydrography and Nautical Charting in the Republic

IIHHOO CCaappaacciittyy BBuuiillddiinngg PPrrooggrraammmmee IIHHOO RReeppoorrtt oonn HHyyddrrooggrraapphhyy aanndd NNaauuttiiccaall CChhaarrttiinngg iinn TThhee RReeppuubblliicc ooff VVaannuuaattuu December 2011 (publliished 4 Apriill 2012) This work is copyright. Apart from any use permitted in accordance with the Berne Convention for the Protection of Literary and Artistic Works (1886), and except in the circumstances described below, no part may be translated, reproduced by any process, adapted, communicated or commercially exploited without prior written permission from the International Hydrographic Bureau (IHB). Copyright in some of the material in this publication may be owned by another party and permission for the translation and/or reproduction of that material must be obtained from the owner. This document or partial material from this document may be translated, reproduced or distributed for general information, on no more than a cost recovery basis. Copies may not be sold or distributed for profit or gain without prior written agreement of the IHB and any other copyright holders. In the event that this document or partial material from this document is reproduced, translated or distributed under the terms described above, the following statements are to be included: “Material from IHO publication [reference to extract: Title, Edition] is reproduced with the permission of the International Hydrographic Bureau (IHB) (Permission No ……./…) acting for the International Hydrographic Organization (IHO), which does not accept responsibility for the correctness of the material as reproduced: in case of doubt, the IHO’s authentic text shall prevail. The incorporation of material sourced from IHO shall not be construed as constituting an endorsement by IHO of this product.” “This [document/publication] is a translation of IHO [document/publication] [name]. -

89 the DISCOVERY of TORRES STRAIT by C.APT.AIN

89 THE DISCOVERY OF TORRES STRAIT By C.APT.AIN BRETT HILDER, M.B.E. (Presented to a meeting of the Royal Historical Society of Queensland on 26 June 1975) The whole area of Torres Strait is part of the continental shelf which joins Australia and New Guinea over hundreds of miles. The shelf rises to a shallower bank of nine fathoms and less, extending north from Cape York Peninsula, where it is about 60 miles wide, to a long stretch of the New Guinea coastline. This bank is no doubt mainly of coral, but the larger islands on it are of rock, indicating a soUd foundation. Owing to the large area of the Strait, only the regular shipping tracks are well charted, leaving large areas blank except for warnings of unknown shoals and reefs. The tidal streams in the passages are very strong, reaching speeds up to eight knots in some places. Navigation in the Strait is therefore hazardous, requiring the use of pilots for all except local vessels. The pilots, all experienced Master Mariners, also take ships through the Great Barrier Reef, and form an elite corps named the Queensland Coast and Torres Strait Pilot Service. The first Europeans to sight any part of the Strait were the Dutch, under Willem Janszoon in the small vessel Dyfken, some time in the months of March and April 1606. They made a very fine chart of the western side of the Strait and its islands, but they regarded the area as a bight of shallow water in the coastline of New Guinea, and therefore thought that Cape York Peninsula was an extension of the New Guinea coastline. -

V07VUGO04 Project Officer

Project Officer - Language & Culture Malakula Kaljorol Senta (MKS) Lakatoro, Malakula Island, Vanuatu 24 months September 2008 - September 2010 The Malakula Kaljorol Senta (Malakula Cultural Centre) MKS is the only provincial branch of the main Vanuatu Cultural Centre based in Port Vila. Situated at the Provincial Centre at Lakatoro, Central Malekula the centre is very important and plays a very important role in preventing and preserving the cultures of the people of Malekula. It was established in 1991 to be the doorway and also, preserve and promote the cultures of Malekula. The main objectives for the Malakula Cultural Centre (MKS) are to: upgrade the custom and cultures of Malekula for the attraction of visitors and interested custom role from Malekula advertise the section headings based on MCC attach with the Vanuatu National Museum. collect and preserve artifacts of historical, customary and cultural importance used and practiced on the island of Malakula provide temperature and humidity control for the audio visual equipment. Tasks carried out by the Malakula Cultural Centre include: Carry out primary and secondary school visits Officer giving talks representing cultures in developing the Malampa REDI (5 years development plan). Page 1 of 4 Give assistance to researchers and other people sent by the Vanuatu Cultural Centre to do work on Malekula. To learn more visit the website at: http://www.vanuatuculture.org/ Need of language documentation and orthography development in communities in Malakula where there are not yet agreed orthographies Development of additional vernacular literacy materials and assistance in training teachers Support the Malakula Kaljoral Senta in the development of work plans and long-term plans Literacy manuals developed Establishment of vernacular literacy programs in Grade 1 in as many schools as possible in the Malampa province as per the Ministry of Education policy. -

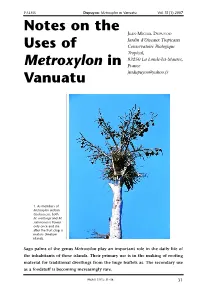

Notes on the Uses of Metroxylon in Vanuatu

PALMS Dupuyoo: Metroxylon in Vanuatu Vol. 51(1) 2007 Notes on the JEAN-MICHEL DUPUYOO Jardin d’Oiseaux Tropicaux Uses of Conservatoire Biologique Tropical, 83250 La Londe-les-Maures, Metroxylon in France Vanuatu [email protected] 1. As members of Metroxylon section Coelococcus, both M. warburgii and M. salomonense flower only once and die after the fruit crop is mature (Anatom island). Sago palms of the genus Metroxylon play an important role in the daily life of the inhabitants of these islands. Their primary use is in the making of roofing material for traditional dwellings from the huge leaflets as. The secondary use as a foodstuff is becoming increasingly rare. PALMS 51(1): 31–38 31 PALMS Dupuyoo: Metroxylon in Vanuatu Vol. 51(1) 2007 Vanuatu is an archipelago composed of more 60–80 cm at chest height (Fig. 3). The leaves than 80 islands, stretching over 850 kilometers can be more than 6 meters long with leaflets on a southeast to northwest line. Situated in 100–190 cm long and 14–19 cm wide. The the southwestern Pacific Ocean, Vanuatu is a petioles have long and flexible spines (Fig. 4). neighbor of the Solomon Islands to the northwest, New Caledonia to the southwest Varieties of Natangura Palms and Fiji to the east. Its total surface area is Metroxylon warburgii is known as Natangura 12,189 km2, and the eight biggest islands throughout the archipelago. This palm is represent 87% of that surface (Weightman highly polymorphic and inhabitants 1989). differentiate and name several varieties. The The Genus Metroxylon in Vanuatu variety Ato, indigenous to the south of Espiritu Santo, is often taller than 15 meters (Fig.