An Island Between’: Multiple Migrations and the Repertoires of a St Helenian Identity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

St Helena Celebrates Cultural Diversity on St Helena's

www.sams.sh THE South Atlantic Media Services, Ltd. Vol. 9,SENTINEL Issue 10 - Price: £1 “serving St Helena and her community worldwide” Thursday 27 May 2021 St Helena celebrates Cultural Diversity on St Helena’s Day Proposals to allow wealthy people purchase Permanent Residency “well received” say SHG The Global Saint Community New Burial Ground identified for Map by Saint Cooks “Liberated Africans” 2 www.sams.sh Thursday 27 May 2021 | THE SENTINEL THE SENTINEL | Thursday 27 May 2021 www.sams.sh 3 OPINION YOUR LETTERS ST HELENA NEWS SENTINEL Quiet Magistrate’s Court £2m under spend in SHG budget session predicted COMMENT Andrew Turner, SAMS Andrew Turner, SAMS Andrew Turner, SAMS overseas medical referral budget St Helena’s future is now resting and the TC budget not being fully in the hands of the UK Governments utilised. Privy Council who will decide on There was also an over collection the constitutional amendments of customs duties and an under needed to change St Helena from its collection in revenue in the Children current system of Governance to the and Adults Social Care Directorate Ministerial System. of £54k because fewer individuals Amendments to St Helena’s are eligible/able to pay for care constitution can only be made by services. a UK Order in Council which is an Order made by the Queen acting on According to the report of the the advice of the Privy Council. meeting, “Deputy Financial But what is the Privy Council and Secretary explained that there is this really the right group to be might be further changes to the deciding our fate? It was a comparatively quiet Thomas “in a hostile manner.” SHG is predicting an under spend of £2m was indicated, which was final outturn position as year-end Essentially the Privy Council is an session of the St Helena Magistrates According to the Magistrates of £2m for this financial year. -

Cultural Ecosystem Services in St Helena

South Atlantic Natural Capital Project; Cultural ecosystem services in St Helena. Dimitrios Bormpoudakis Robert Fish Dennis Leo Ness Smith April 2019 Review table Name Reviewed by Date Version 1 Ness Smith 17/04/19 Version 2 Tara Pelembe and Paul 30/04/19 Brickle Version 3 SHG 16/05/19 Version 4 Acknowledgements: We would like to thank the NCA project St Helena Advisory Group and everyone who took part in the survey. This research was funded by The UK Government via the Conflict, Security and Stability Fund. Suggested citation: Bormpoudakis, D., Fish, R., Leo, D., Smith, N. (2019). Cultural Ecosystem Services in St Helena. Final Report for the South Atlantic Overseas Territories Natural Capital Assessment For more information, please contact the South Atlantic Environmental Research Institute (SAERI) at [email protected] or visit http://south-atlantic-research.org PO Box 609, Stanley Cottage Stanley FIQQ 1ZZ Falkland Islands Tel: +500 27374 www.south-atlantic-research.org SAERI is a registered Charity in England and Wales (#1173105) and is also on the register of approved Charities in the Falkland Islands (C47). SAERI also has a wholly-owned trading subsidiary – SAERI (Falklands) Ltd – registered in the Falkland Islands. CULTURAL ECOSYSTEM SERVICES IN THE ISLAND OF ST HELENA Dimitrios Bormpoudakis & Robert Fish, School of Anthropology and Conservation, University of Kent Dennis Leo, St Helena National Trust Ness Smith, South Atlantic Environment Research Institute Version 3.0 – 21 May 2019 --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 1. BACKGROUND ON ST HELENA Saints know the value of nature; we want to turn this knowledge into data that will help in decision making across a range of sectors. -

April GAZ 2014.Pmd

The St. Helena Government Gazette Vol. XLXII. Published by Authority No. 28. Annual Subscription Present Issue £13.75 Post Free 30 April 2014 £1.25 per copy No. Contents Page 51.APPOINTMENTS AND STAFF CHANGES ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... 207 52.APPOINTMENT OF ACTING ADMINISTRATOR, ASCENSION ISLAND... ... ... ... ... 208 53.APPOINTMENT OF DIRECTORS TO ENTERPRISE ST HELENA BOARD OF DIRECTORS ... ... 209 54.APPOINTMENT OF DEPUTY COMMISSIONER OF INCOME TAX ... ... ... ... ... 209 55.APPOINTMENTS OF COLLECTOR OF CUSTOMS AND EXCISE AND DEPUTY COLLECTOR OF CUSTOMS AND EXCISE ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... 209 56.APPOINTMENTS OF MEMBERS AND DEPUTY CHAIRMEN OF COUNCIL COMMITTEES ... ... 210 57.APPOINTMENT OF ACTING ADMINISTRATOR, ASCENSION ISLAND ... ... ... ... ... 210 58. ST HELENA COMPANIES REGISTRY ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... 210 59. CORRECTION TO GAZETTE NOTICE NO 24 DATED 31 MARCH 2014... ... ... ... ... 211 No.51. APPOINTMENTS AND STAFF CHANGES His Excellency the Governor has approved the following appointments and staff changes from the dates shown: Appointments Mrs Kerry Yon, Assistant Director (Life Long Learning) Education and Employment Directorate... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... 1 April 2014 Mrs Wendy Benjamin, Assistant Director (Schools) Education and Employment Directorate... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... 1 April 2014 Miss Kathryn Squires, Advisory Teacher English, Education and Employment Directorate... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... 1 April 2014 Mr Clarence Youde, Maintenance Worker, Environment -

Rebecca Lawrence Becomes First St Helenian Veterinary Doctor

THE South Atlantic Media Services, Ltd. www.sams.sh Vol. 6,SENTINEL Issue 18 - Price: £1 “serving St Helena and her community worldwide” Thursday 03 August 2017 Rebecca Lawrence becomes fi rst St Helenian veterinary doctor “As a Saint, I hope this proves that what we have at home is enough for people to achieve high standards,” she said. “If you don’t think too much of yourself, and are willing to make sacrifi ces and put in the work, then I think St Helena is a great place to come from.” ... page 13 Bahamas Team Returns Schools Open Days Rosie... page Bargo 13 talks about A look back at car ... page 30-32 her new cocktail bar history on St Helena ... page 5 ... page 14 First Formal Legislative Council Meeting ... page 4 2 www.sams.sh Thursday 03 August 2017 | THE SENTINEL ST HELENA SNIPPETS Photo 2: The usual way to get large cargo from Snapshots the RMS onto the wharf. Photo by Emma Weaver. of the week News bites from this work week Emma Weaver, SAMS Monday, July 31 Pilling Open Day: (see page 30) Digital Strategy Draft public consultation meeting: 7pm in the Jamestown Community Centre worsen.” Public Library Closes Temporarily: “The The RMS fi nally departed St Helena, head- Public Library in Jamestown will be closed Tuesday, August 1 ed to Ascension, at 18:05 with 54 passengers temporarily from Wednesday, 2 August 2017, Rainbow of St James Bay: See Photo 1. A (who had boarded at noon) and 56 crew on- to allow renovation works to take place. -

The Sentinel 29 September 2016

THE South Atlantic Media Services, Ltd. www.sams.sh Vol. 5,SENTINEL Issue 26 - Price: £1 “serving St Helena and her community worldwide” Thursday 29 September 2016 HISTORIC TREE REMOVED Castle Gardens only GREAT COMMITMENT 6 nurses take on studying a degree alongside a full-time job Banyan Tree Removed see page 11 due to Weevil Infestation Andrew Turner, SAMS Forestry work has been ongoing in the Castle Gardens this week. As part of this trees are being pruned and checked to see if they are healthy. During one of these routine checks it was dis- covered that the Garden’s only banyan tree had become infested with weevils. As weevils only house themselves in already dead trees it had be- come necessary to remove the tree completely to protect both the public and neighbouring trees. ANRD Forestry Offi cer Mira Young told The Sen- tinel “This is part of our annual program, the gar- dens are crown estates and we have responsibility for the trees. The aim is to keep the trees safe for users of the public gardens,” The wood from this tree will be fi rst offered to craftsmen who want to work with the wood. Any wood left over will be used either for fi rewood or chipped and made into a mulch that can be used as a fertiliser. The Forestry Division will continue with their pruning work through Jamestown over the com- ing weeks. Members of the ANRD forestry team 2 www.sams.sh Thursday 29 September 2016 | THE SENTINEL ST HELENA SNIPPETS Grand Fish-Fry on Longwood Green Engaging with the Community sisting of a selection of fresh fi sh, chips, yam, Ferdie Gunnell, SAMS etc. -

Examples of Risks on St Helena Include

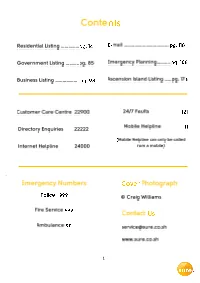

1 2 3 4 • • • • • • • • • 5 6 7 ? 8 9 10 11 12 13 RESIDENTIAL CATEGORY ALPHABETICAL LISTING 14 A ADAMS, Anita & Alexander Clay Gut, Half Tree Hollow 23452 ADAMS, Barbara Nr Princes Lodge, St. Pauls 25575 ADAMS-DUNCAN, Jayne Hunts Vale, Alarm Forest 24917 ALLEN, Robert & Delia Lower Farm Lodge, St. Pauls 24440 ANDERSON, Nicola Sapper Way, St. Pauls 23417 ANDERSON, Patrick Rock Rose, Sandy Bay 24859 ANDREWS, Ann No. 3 R.E. Yard, Ladder Hill 23881 ANDREWS, Brian Wireless Station Road, Half Tree Hollow 23955 ANDREWS, Dorothy New Ground, St. Pauls 24036 ANDREWS, Fredrica Millfield, Longwood 24513 ANDREWS, Gemma Upper Cow Path, Nr High Knoll 25366 ANDREWS, Isabel Nr Evergreen Tree, Half Tree Hollow 23152 ANDREWS, Jessina The Boot, Longwood 25618 ANDREWS, Johnny Johants, New Ground 23040 ANDREWS, Kenickie S The Boot, Longwood 23957 ANDREWS, Kenneth Half Tree Hollow 23879 ANDREWS, Merrill Deadwood, Longwood 24975 ANDREWS, Patrick Cow Path, Half Tree Hollow 23021 ANDREWS, Roy & Jennifer Nr White Wall, Half Tree Hollow 23019 ANDREWS, Sidonio S Oasis Bar, Cow Path 23607 ANDREWS, Sonny No. 4 Cow Path, Half Tree Hollow 23880 ANDREWS, Steven No. 4 Cow Path, Half Tree Hollow 25439 ANNIES LAUNDRETTE, Napoleon Street, Jamestown 22435 c/o Anne Wolstenholme ANNS PLACE, Jane Sim Castle Gardens, Jamestown 22797 ANTHONY, Cecil Half Tree Hollow 23993 ANTHONY, Eileen No. 5 Barracks Square, Jamestown 22581 ANTHONY, Jolene No. 5 Harris Flats, Jamestown 25502 ANTHONY, Neil James Nr Longwood Clinic, Longwood 23728 ANTHONY, Patrick White Gate, St Pauls 23287 ANTHONY, Robert J Red Hill, Nr High Knoll 23971 15 A ANTHONY, Stephen Ladder Hill, Half Tree Hollow 23015 ANTHONY, Sylvia Nr. -

The Sentinel 15 September 2016

THE South Atlantic Media Services, Ltd. www.sams.sh Vol. 5,SENTINEL Issue 24 - Price: £1 “serving St Helena and her community worldwide” Thursday 15 September 2016 STAY SAFE ST HELENA Local Emergency Services Receive Rescue Training see page 7 Banking For The Future BRIGADE ON Local Debit Cards Coming Soon THE BRIDGE see page 4 1 YEAR SINCE FIRST FLIGHT back over the years,” BOSH HR and Customer Services Offi cer, Joey George, explained. “It is hoped that it will improve services around the island and help customers to gain access to cash outside of normal working hours for the bank.” Damien O’Bey, SAMS The work needed to bring this service, which the rest of world now takes for granted, to Saints has been immense. The Bank, along with Account transfer slips and sifting through large amounts of change support from its current software providers, International Financial could become a thing of the past if the Bank of St Helena’s (BOSH) Systems (IFS), has designed and built its own app, and will print its pilot project to introduce local debit cards proves to be successful. own debit cards that will share many of the same features as cards BOSH will run their local debit card trial from November 2016 and from other banks. The cards have also been future proofed should hope to roll out the service after feedback received from the trial, is BOSH decide to expand their services. analysed. To be a part of the pilot run of the service, anyone can fi ll out “We wanted something that would work for everybody,” explained and hand in the slips the Bank has placed into this week’s newspapers. -

St Helena Independent

Est. 2005 VOLUME XIII ISSUE 39, 31st AUGUST 2018, PRICE £1 An independent newspaper in association with Saint FM and St Helena Online What is a Crisis and How do NEW PUBLIC SOLICITOR you Know when you Face one? SET TO ‘HIT THE GROUND RUNNING’! Wet Reading Sports Day Jonathan Clingham “Dottie Comes Home on the Plane” What is a crisis and how do you know when you face one? The definition of a crisis given in one dictionary is, “a time of booked flights were common. It had to be cash because intense difficulty or danger” and “a time when a difficult or credit card and debit cards were not accepted and if the cash important decision must be made”. This seems accurate; is could not be produced the only ‘choice’ for hapless passen- St Helena facing a time of intense difficulty when difficult and gers was to remain in St Helena for at least a further week. important decisions need to be made. The answer must be a Apart from the chaos and cost caused to plane passengers resounding YES! the nightmare scenario they had to endure means they will Cllr Lawson Henry said on Saint FM we are not in crisis, we never want to even hear the name St Helena again and they still live in a very safe environment, the community spirit on will doubtless dissuade anyone and everyone they come in this small, remote island remains strong. There are, Lawson contact with from ever thinking of coming within a thousand said, many other places in the world much worse off. -

Colonial Annual Report 1950 & 1951

COLONIAL OFFICE REPORT ON ST. HELENA FOR THE YEARS 1950 and 1951 Contents PAGE PART I Review of the Years 1950 and 1951 3 PART II CHAPTER 1 Population . 5 CHAPTER 2 Occupations, Wages and Labour Organisation . 6 CHAPTER 3 Public Finance and Taxation 7 CHAPTER 4 Currency and Banking . 14 CHAPTER 5 Commerce . 15 CHAPTER 6 Production . 17 CHAPTER 6 Social Services 20 CHAPTER 8 Legislation . 25 CHAPTER 9 Justice, Police and Prisons 27 CHAPTER 10 Public Utilities . 28 CHAPTER 11 Communications . 29 PART III CHAPTER 1 Geography and Climate 30 CHAPTER 2 History . 32 CHAPTER 3 Administration . 33 CHAPTER 4 Weights and Measures . 33 CHAPTER 5 Newspapers and Periodicals 33 PART IV Ascension 34 PART V Tristan da Cunha . 36 APPENDIX I Colonial Development and Welfare Schemes 47 II Fifty years' statistics of Population, Births, Deaths, Marriages, Divorces and Judicial Separations . 48 III Ten years' statistics of Supreme Court cases . 49 IV Ten years' statistics of other Court cases . 50 READING LIST . 52 MAPS . At end LONDON : HER MAJESTY'S STATIONERY OFFICE 1952 PART I Review of the Years 1950 and 1951 THE Governor, Sir George Joy, K.B.E., C.M.G., returned to the Island from leave on 21st May, 1950. From 6th to 1 1 th July, 1951, the Governor paid an official visit to the Dependency of Ascension Island. Mr. K. H. Clarke, the Government Secretary, was awarded the O.B.E. in the Birthday Honours, 1950. Mr. Clarke left the island in May, 1950, on completion of his tour, and was succeeded by Mr. -

St Helena (To

Important Bird Areas in Africa and associated islands – St Helena, Ascension Island and Tristan da Cunha, including Gough Island ■ ST HELENA AND THE DEPENDENCIES OF ASCENSION ISLAND AND TRISTAN DA CUNHA, INCLUDING GOUGH ISLAND BEAU W. ROWLANDS Ascension Frigatebird Fregata aquila. (ILLUSTRATION: DAVE SHOWLER) GENERAL INTRODUCTION middle zone, 330–600 m, has an extensive vegetation cover of shrubs and grasses, but also some open ground. The humid zone, above St Helena is an Overseas Territory of the United Kingdom; 600 m, has a luxuriant plant cover that, in places, amounts to a Ascension Island and Tristan da Cunha, including Gough Island, cloud-forest, where introduced vegetation flourishes. This includes are administered as Dependencies of St Helena. Acacia, Alpinia, Araucaria, Bambusa, Buddleia, Erythrina, Eucalyptus, Ficus, Grevillia, Juniperus, Mangifera, Musa, Olea, ■ Ascension Island Pinus, Podocarpus and Psidium. Ascension is an isolated and relatively young oceanic island, lying The human population is about 1,000, made up of civilians some 100 km west of the mid-Atlantic Ridge, 1,504 km south-south- working for contractors to the RAF and USAF, and a small number west of Liberia (Cape Palmas), and 2,232 km from Brazil (Recife). of military personnel. The personnel are mainly from the UK, USA The nearest land is St Helena, 1,296 km to the south-east. Apart and St Helena, none of whom are permanent residents. User from a few beach deposits (shell-sand), the island is entirely volcanic organizations include the BBC World Service, Cable & Wireless in origin and has a rugged terrain. The relatively low and dry Communications plc, the RAF and the USAF, with their support western part is dominated by scoria cones and basaltic lava-flows, staff. -

Downloaded Dec

ST HELENA—ON THE CUSP OF GLOBALIZATION Tiffany Prysock Devereux A thesis submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Journalism and Mass Communication in the School of Journalism and Mass Communication. Chapel Hill 2012 Approved by: Dean Jan Yopp Dr. James Peacock Associate Professor Pat Davison © 2012 Tiffany Prysock Devereux ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT TIFFANY PRYSOCK DEVEREUX: St Helena—On the Cusp of Globalization (Under the direction of Dean Jan Yopp, Dr. James Peacock and Associate Professor Patrick Davison) In the next five years, we have a rare opportunity to witness transformation of a society toward a globalized world market. St Helena, a British Overseas Territory, is only accessible by ship—the same vehicle used to access the island since its discovery in 1502. Throughout its 510 years, the island’s economic prosperity has risen and fallen through globalizing trends due to its remote location in the middle of the South Atlantic Ocean. The island’s economy has faltered since the 1960s and it currently receives British government aid in the form of subsidies. In 2015, airport construction is expected to be complete which may catapult the island—once again—into the globalized world through tourism. This thesis and three-part documentary seeks to record the lives of the islanders by looking at the economy, social structure and identity of the islanders in 2009, prior to airport construction. This documentary is intended to be a baseline to compare the islanders’ lives after the airport construction is complete. -

SENTINEL Issue 25 - Price: £1 “Serving St Helena and Her Community Worldwide” Thursday 21 September 2017 Ascension Releases Airlink Price and Start Date ...See Page 3

www.sams.sh THE South Atlantic Media Services, Ltd. Vol. 6,SENTINEL Issue 25 - Price: £1 “serving St Helena and her community worldwide” Thursday 21 September 2017 Ascension Releases Airlink Price and Start Date ...See page 3 Rupert’s remains re- Appeal argues St Helenians membered ...See pages 25-26 only worth 1/3 of UK citizens ...See page 15 Sure celebrates two years of mobile service ...See page 7 Fruit and veg statistics from Legco review latest RMS voyage ...See page 37 ...See pages 9-11 UN World Day of Peace exhibit opens ...See page 47 Annual SPCA quiz night ...See page 5 Saint’s Kitchen...See pages 32-33 2 www.sams.sh Thursday 21 September 2017 | THE SENTINEL THE SENTINEL | Thursday 21 September 2017 www.sams.sh 3 ST HELENA SNIPPETS ST HELENA SNIPPETS Donna Crowie, SAMS Ascension Air Access Announcement Name: Cedella Marie Fowler Sisters forever DOB: 24th August 2017 Ascension prices and start date released, access discussions continue Weight: 7lb 8oz Emma Weaver, SAMS Time: 19:24 Parents: Kanisha Crowie and Stephen Fowler Yet more flight updates have appeared “Baby Cedella is great and over the past week. very happy,” mummy said. Most significantly, on Ascension Island, Big sister, Shakara, is so the long-awaited flight prices and a start happy to have her little sister. date for the SA Airlink bridge between St Shakara helps mummy with Helena Island (HLE) and Ascension Island feeding Cedella and putting (ASI) have been announced. nappies in the bed but she also Flights will start Saturday, Nov. 18, and loves waking her sister up.