Dreams in Real Time

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

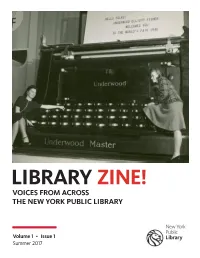

Library Zine! Voices from Across the New York Public Library

LIBRARY ZINE! VOICES FROM ACROSS THE NEW YORK PUBLIC LIBRARY Volume 1 • Issue 1 Summer 2017 LIBRARY ZINE! Greetings creative VOICES FROM ACROSS THE NEW YORK PUBLIC LIBRARY Volume 1 • Issue 1 New Yorkers! Summer 2017 EDITORIAL TEAM Welcome to the first issue of The New York Public Library’s literary magazine Library Zine!, a creative writing magazine containing original writing and visual art submitted by library patrons and staff of all ages. We encourage Whitney Davidson-Rhodes submissions in all languages and personal styles so that we can better reflect Young Adult Librarian the diverse communities the New York Public Library serves. Wakefield Library New York prides itself on being a center of culture and creativity. Even Adena Gruskin through troubling times, our words and our pictures comfort us and show our Young Adult Librarian imagination knows no bounds. This is a truth that can be recognized daily at High Bridge Library any of the New York Public Library’s branches. Tabrizia Jones To enter a circulating branch of The New York Public Library is to enter the Young Adult Librarian realm of “real” New Yorkers. Distant from the vacationer’s dream of what this Sedgwick Library city might be, each branch of NYPL provides those of us who require the extraordinary amounts of patience and fortitude necessary to continue our Karen Loder grind in the midst of so much noise with space to realize our personal dreams Adult Librarian and pursuits. As community centers in this urban scramble, the Library is a Sedgwick Library necessary reprieve where the city dweller can recognize themselves and the questions or epiphanies this environment inspires. -

Hamburgs Top-821-Hitliste

Hamburgs Top‐821‐Hitliste Rang Wird wann gespielt? Name des Songs Interpret 821 2010‐04‐03 04:00:00 EVERYBODY (BACKSTREET'S BACK) BACKSTREET BOYS 820 2010‐04‐03 04:03:41 GET MY PARTY ON SHAGGY 819 2010‐04‐03 04:07:08 EIN EHRENWERTES HAUS UDO JÜRGENS 818 2010‐04‐03 04:10:34 BOAT ON THE RIVER STYX 817 2010‐04‐03 04:13:41 OBSESSION AVENTURA 816 2010‐04‐03 04:27:15 MANEATER DARYL HALL & JOHN OATES 815 2010‐04‐03 04:31:22 IN MY ARMS KYLIE MINOGUE 814 2010‐04‐03 04:34:52 AN ANGEL KELLY FAMILY 813 2010‐04‐03 04:38:34 HIER KOMMT DIE MAUS STEFAN RAAB 812 2010‐04‐03 04:41:47 WHEN DOVES CRY PRINCE 811 2010‐04‐03 04:45:34 TI AMO HOWARD CARPENDALE 810 2010‐04‐03 04:49:29 UNDER THE SURFACE MARIT LARSEN 809 2010‐04‐03 04:53:33 WE ARE THE PEOPLE EMPIRE OF THE SUN 808 2010‐04‐03 04:57:26 MICHAELA BATA ILLC 807 2010‐04‐03 05:00:29 I NEED LOVE L.L. COOL J. 806 2010‐04‐03 05:03:23 I DON'T WANT TO MISS A THING AEROSMITH 805 2010‐04‐03 05:07:09 FIGHTER CHRISTINA AGUILERA 804 2010‐04‐03 05:11:14 LEBT DENN DR ALTE HOLZMICHEL NOCH...? DE RANDFICHTEN 803 2010‐04‐03 05:14:37 WHO WANTS TO LIVE FOREVER QUEEN 802 2010‐04‐03 05:18:50 THE WAY I ARE TIMBALAND FEAT. KERI HILSON 801 2010‐04‐03 05:21:39 FLASH FOR FANTASY BILLY IDOL 800 2010‐04‐03 05:35:38 GIRLFRIEND AVRIL LAVIGNE 799 2010‐04‐03 05:39:12 BETTER IN TIME LEONA LEWIS 798 2010‐04‐03 05:42:55 MANOS AL AIRE NELLY FURTADO 797 2010‐04‐03 05:46:14 NEMO NIGHTWISH 796 2010‐04‐03 05:50:19 LAUDATO SI MICKIE KRAUSE 795 2010‐04‐03 05:53:39 JUST SAY YES SNOW PATROL 794 2010‐04‐03 05:57:41 LEFT OUTSIDE ALONE ANASTACIA 793 -

The Carroll News

John Carroll University Carroll Collected The aC rroll News Student 4-22-2010 The aC rroll News- Vol. 86, No. 19 John Carroll University Follow this and additional works at: http://collected.jcu.edu/carrollnews Recommended Citation John Carroll University, "The aC rroll News- Vol. 86, No. 19" (2010). The Carroll News. 808. http://collected.jcu.edu/carrollnews/808 This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the Student at Carroll Collected. It has been accepted for inclusion in The aC rroll News by an authorized administrator of Carroll Collected. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Students participated in Iceland volcano Humans vs. Zombies eruption causes travel across campus, p. 4 problems, p.12 THE Thursday,C AprilARROLL 22, 2010 Serving John Carroll University Since N1925 EWSVol. 86, No. 19 Spring concert Taxed enough already fails to ‘take As Tea Party rallies are held across the nation on tax day, JCU you there’ students organized their own protest on campus Jayne McCormack came out to the event on Thursday, tives, said that he was very happy Staff Reporter April 15. They protested current U.S. with the turnout at the Tea Party. Less than 17 percent of government policies and spending, He said, “It’s been a really excel- John Carroll students and the most specifically health care. lent turnout. I’m so glad that the Tea JCU students show up for University Heights community “Tea” generally stands for “taxed Party is reaching young people.” came together to hold a Tea Party enough already,” a slogan of the Tea Not only JCU students were pres- on the quad, one of many being held Party movement, which is a national ent at the protest. -

The Echo 04.23.14

SNU Storm baseball senior Teapioca Lounge: bubble weekend tea heaven Read on page 4 Read on page 9 April 23, 2014 Volume 85, Issue 26 echo.snu.edu 6612 NW 42nd St. Bethany, OK 73008 (405) 491-6382 SNU students Spring break at NASA Grace Williams, Business Manager told us about the competitions and Over spring break, Angela the work they do that is funded by Rhodes, Director of Career Ser- the Alabama Space Grant.” vices, and Mary Jo Galbraith, ju- The next day, they went to nior physics major, attended the the U.S. Space and Rocket Cen- NASA workforce development ter which houses exhibits on the trip to Huntsville, Alabama for space race, rocket development, universities participating in the construction and demolition and Oklahoma NASA Space Grant military equipment of the future. Consortium (OSGC). Trip partici- Galbraith and Rhodes got to see pants included students interested an IMAX film about deep space in aeronautics, space science and exploration. technology and related fields. Galbraith said, “My favorite On day one, Rhodes and Gal- part of the day was the giant game braith toured the Marshall Space of jenga that was played by a few Flight Center and later the Univer- of us in the construction/archi- sity of Alabama to see their Space tecture exhibit. We may or may Hardware Club. not have broken the record for the Galbraith said, “We toured sev- tallest tower built with their build- eral different labs and heard from ing blocks.” scientists working on projects for The final day of the trip was the Space Launch System, materi- a morning hike to Burritt on the als manufacturing, environmental Mountain which was Huntsville’s testing and so much more. -

Aussie Add-Ons Welcome to Get Messy Aussie Add-Ons (Thanks to Mel Neumann -South Australia- for the Name!) in This Second Issue

Messy Church Get Messy: Aussie Add-Ons Welcome to Get Messy Aussie Add-Ons (thanks to Mel Neumann -South Australia- for the name!) In this second issue • Reflections on the Messy Church International Conference from Judyth Roberts • Messy church Music: Keeping it Real, Relaxed and Resourced (including a starter set of songs from diverse musical styles and ways to facilitate intergenerational musical engagement) • Joy Marshall’s info graphic on All age faith formation • Celebration ideas for Bible engagement to accompany the themes in Get Messy: Luke 17:11- 19, Matt 5:13, Psalm 23, Luke 1:26-38 Get Messy Aussie Add-ons is a supplement to Get Messy BRF addressing Australian contexts, in line with the Messy Church value of local grass roots innovation, contextualisation and creativity. Messy Church International Conference, 2016 In May I was among 220 people from 12 countries and many denominations who attended the International Messy Church Conference in the UK. More than 20 Australians were there as we gathered to celebrate what God is doing through Messy Church. We were welcomed and affirmed by the Archbishop of Canterbury in a taped address. Archbishop Justin Welby described Messy Church beautifully as “a gift of the Spirit to the church… creating a circle of love that joins people together with Christ at the centre.” BRF Chief Executive Richard Fisher, Lucy Moore, Jane Leadbetter, Martyn Payne and other BRF staff were generous and playful hosts, ensuring the conference went smoothly. There were two inspiring keynote addresses by George Lings based on his research of Messy Church in the UK. -

Apogee Magazine Spring Two Thousand and Sixteen

Department Apogee Magazine Spring Two Thousand and Sixteen Department Apogee Magazine: Spring Two Thousand and Sixteen We ask for first publication rights, after which Copyright returns to the author. No portion of Apogee Magazine may be reproduced without permission. All rights reserved. All submissions should be sent to: [email protected]. Include a cover letter with a 2-3 sentence biography. Produced with the generous support of the English Department at High Point University. Editorial Board: Dr. Charmaine Cadeau Jacquie Cafasso Brittany Gentilhomme Michael Heslink Cami Kockritz Liz Pruitt Angelica Stabile Taylor Tedford Editorial Office: Department of English Norcross 211 High Point University One University Parkway High Point, North Carolina USA 27268 Email: [email protected] Cover Art: Fish by Susan MacRae Featured Artists: Susan MacRae's art comes from her daily drawing practice. Jane Callahan's work is inspired by nature. POETRY Lauryn Polo Hope 6 The man with the slinky is leading the parade 8 Homecoming 10 Joanna Fuhrman Still Life with Island 12 I Have a Secret Crush on Everyone in the World 14 Boredom 16 History Lesson #3 18 Cranberry Juice Moon 20 Jean Rodenbough The Way of Geese 26 Taylor Tedford Bricks 32 Nothing 33 Missing Me 34 María Castro Domínguez Rewriting the End 36 Lynn White Caged 44 Matt Dugan City of Glass 46 Sam Schoenfeld Denouement 52 Jacquie Cafasso Celery 54 Senses 56 Joe Elliot Untitled 58 Grand Theft Auto Five (Walter Has A Cold) 60 Why Busses On Longer Routes Love Each Other And Tend To Clump 62 Robinson Crusoe 64 LYRICS Tara Needham Spies (No more) 22 Flash 24 FICTION Alice Zorn Five Roses (excerpt) 28 Christian Garber Who Even Watches This 38 Christina McAuliffe The Disease 48 CONTRIBUTORS 66 6 Hope Crane by Susan MacRae Words by Lauryn Polo Art by Susan MacRae Her eyes weren’t transparent like the water in aquariums, instead they carried everything she saw, eroded emotions, some not her own, into her mind. -

Dance Charts Monat 04 / Jahr 2010

Dance Charts Monat 04 / Jahr 2010 Pos. VM Interpret Titel Label Punkte +/- Peak Wo 1 54 DARIUS & FINLAY & SHAUN BAKER ZEIGT MIR 10 (EXPLODE 3) SONY 9042 +53 1 2 2 5 STROMAE ALORS ON DANSE UNIVERSAL 8635 +3 2 4 3 6 AKUSTIKRAUSCH OHRBASSMUS SONY 8592 +3 3 2 4 3 DJ GOLLUM VS. BASSLOVERS UNITED NARCOTIC ZOOLAND 6627 -1 3 3 5 2 DAVID GUETTA FT. KID CUDI MEMORIES EMI 5888 -3 2 5 6 29 DISCOTRONIC MEETS TEVIN TO THE MOON AND BACK MENTAL MADNESS 4729 +23 6 2 7 28 CASCADA PYROMANIA ZOOLAND / UNIVERSAL 4556 +21 7 2 8 SNAP! RHYTHM IS A DANCER 2010 MINISRTY OF SOUND 4073 0 8 1 9 21 ROB MAYTH FEEL MY LOVE ZOOLAND 4014 +12 9 3 10 1 DJ GOLLUM PASSENGER GLOBAL AIRBEATZ 3794 -9 1 5 11 ANDREW SPENCER & THE VAMPROCKERZ ZOMBIE 2K10 GMG MUSIC / MENTAL 3583 0 11 1 MADNESS 12 7 BROOKLYN BOUNCE VS. ALEX M. & MARC CRAZY MENTAL MADNESS 3471 -5 7 3 VAN DAMME 13 18 SCOTTY LET THE BEAT HIT EM SPLASHTUNES 3323 +5 13 2 14 9 THE DISCO BOYS I SURRENDER SUPERSTAR RECORDINGS 3273 -5 9 4 15 15 GUENTA K. PUSSY KILLER ZENTIMENTAL RECORDS 3024 0 15 2 16 12 JAN WAYNE PRESENTS GORGEOUS X BLACK VELVET CUEPOINT RECORDS 2786 -4 12 3 17 4 ROCKSTROH TANZEN KICK FRESH 2752 -13 3 4 18 13 MASTER BLASTER UNTIL THE END ZOOLAND 2731 -5 13 3 19 116 JASPER FORKS RIVER FLOWS IN YOU (INCL. VOCALS MIXES) KONTOR 2547 +97 19 2 20 DIE ATZEN FRAUENARZT & MANNY MARC ATZIN KONTOR 2442 0 20 1 21 24 LITTLE-H FEAT. -

Dance Charts Monat 05 / Jahr 2010

Dance Charts Monat 05 / Jahr 2010 Pos. VM Interpret Titel Label Punkte +/- Peak Wo 1 1 DARIUS & FINLAY & SHAUN BAKER ZEIGT MIR 10 (EXPLODE 3) SONY 12037 0 1 3 2 3 AKUSTIKRAUSCH OHRBASSMUS SONY 9428 +1 2 3 3 2 STROMAE ALORS ON DANSE UNIVERSAL 7711 -1 2 5 4 8 SNAP! RHYTHM IS A DANCER 2010 MINISRTY OF SOUND 7324 +4 4 2 5 29 DAVID GUETTA & CHRIS WILLIS FEAT. GETTIN OVER YOU EMI 6422 +24 5 2 FERGIE AND LMFAO 6 4 DJ GOLLUM VS. BASSLOVERS UNITED NARCOTIC ZOOLAND 5580 -2 3 4 7 7 CASCADA PYROMANIA ZOOLAND / UNIVERSAL 5127 0 7 3 8 11 ANDREW SPENCER & THE VAMPROCKERZ ZOMBIE 2K10 GMG MUSIC / MENTAL 4637 +3 8 2 MADNESS 9 5 DAVID GUETTA FT. KID CUDI MEMORIES EMI 4536 -4 2 6 10 9 ROB MAYTH FEEL MY LOVE ZOOLAND 4096 -1 9 4 11 81 ALEX M. (I WANNA) FEEL THE HEAT MENTAL MADNESS 3679 +70 11 2 12 20 DIE ATZEN FRAUENARZT & MANNY MARC ATZIN KONTOR 3651 +8 12 2 13 19 JASPER FORKS RIVER FLOWS IN YOU (INCL. VOCALS MIXES) KONTOR 3547 +6 13 3 14 6 DISCOTRONIC MEETS TEVIN TO THE MOON AND BACK MENTAL MADNESS 3255 -8 6 3 15 27 MICHAEL MIND PROJECT FEEL YOUR BODY KONTOR 2832 +12 15 2 16 17 ROCKSTROH TANZEN KICK FRESH 2696 +1 3 5 17 53 LENA MEYER LANDRUT SATELLITE (REMIXES) UNIVERSAL 2664 +36 17 2 18 RICKY RICH VS. DISCO POGO FEAT. SEASIDE PARTY RANDALE SONY 2104 0 18 1 CLUBBERS 19 14 THE DISCO BOYS I SURRENDER SUPERSTAR RECORDINGS 1984 -5 9 5 20 THE DISCO BOYS LOVE TONIGHT SUPERSTAR RECORDINGS 1981 0 20 1 21 10 DJ GOLLUM PASSENGER GLOBAL AIRBEATZ 1909 -11 1 6 22 12 BROOKLYN BOUNCE VS. -

Page 2.Qxd 19.3.2010 14:52 Uhr Seite 12

10-0552_IIHF_IceTimes_April2010.qxp:Page 2.qxd 19.3.2010 14:52 Uhr Seite 12 12 Volume 14 Number 2 April 2010 Norway’s Hove always on call April 2010 Volume 14 Number 2 The golden girl among women’s Published by International Ice Hockey Federation Editor-in-Chief Horst Lichtner Editor Szymon Szemberg Design Jenny Wiedeke international officials By Andrew Podnieks Olympics take the game to the next level Aina Hove's rise to the top of the referees' pool in women's hockey has been swift. The Norwegian didn't referee her first top division game until 2007, and two years later she was in the gold- medal game. But she has been surrounded by hockey her whole life. Her brother was a player; her husband has been a linesman; and, her sister, Marta, was a linesman in 2006 in Turin. Hove tal- ked about her career the day after she officiated the Canada- United States game for gold on February 25, 2010. Norway's men's team isn't a powerhouse, so for a woman it must have MAKING A STAND: Aina Hove has gotten the nod to been even tougher to play. How did you come to love hockey? officiate the last two gold medal games at major inter- national women’s events. In 2009, she called the USA- When I was a kid in Trondheim, my dad made an outdoor rink for the kids Canada final at the Women’s World Championship, to play on. It was a soccer field in the summer. I had nice red, figure ska- while in February, she again got the call to whistle the tes, like any girl. -

Seite 1 Von 315 Musik

Musik East Of The Sun, West Of The Moon - A-HA 1 A-HA 1. Crying In The Rain (4:25) 8. Cold River (4:41) 2. Early Morning (2:59) 9. The Way We Talk (1:31) 3. I Call Your Name (4:54) 10. Rolling Thunder (5:43) 4. Slender Frame (3:42) 11. (Seemingly) Nonstop July (2:55) 5. East Of The Sun (4:48) 6. Sycamore Leaves (5:22) 7. Waiting For Her (4:49) Foot of the Mountain - A-HA 2 A-HA 1. Foot of the Mountain (Radio Edit) (3:44) 7. Nothing Is Keeping You Here (3:18) 1. The Bandstand (4:02) 8. Mother Nature Goes To Heaven (4:09) 2. Riding The Crest (4:17) 9. Sunny Mystery (3:31) 3. What There Is (3:43) 10. Start The Simulator (5:18) 4. Foot Of The Mountain (3:58) 5. Real Meaning (3:41) 6. Shadowside (4:55) The Singles 1984-2004 - A-HA 3 A-HA Train Of Thought (4:16) Take On Me (3:48) Stay On These Roads (4:47) Velvet (4:06) Cry Wolf (4:04) Dark Is The Night (3:47) Summer Moved On (4:05) Shapes That Go Together (4:14) The Living Daylights (4:14) Touchy (4:33) Ive Been Losing You (4:26) Lifelines (3:58) The Sun Always Shines On TV (4:43) Minor Earth Major Sky (4:02) Forever NOt Yours (4:04) Manhattan Skyline (4:18) Crying In The Rain (4:23) Move To Memphis (4:13) Worlds 4 Aaron Goldberg 7. -

Natalie Portman, Fotografiert Von Jim Rakete – Zu Sehen Bei Hilaneh Von Kories >> Seite 12

KONZERT RESTAURANT KINO Indie Die Band The Italienisch Alles Historienepos Sounds bringt die Sonne frisch auf den Tisch – und Rachel Weisz spielt in mit zum „2. St. Pauli Play gemütlich ist’s auch noch „Agora“ eine beherzte Winterfestival“ >> Seite 2 im Il Cantuccio >> Seite 4 Philosophin >> Seite 6 11. bis 17. März 2010 www.abendblatt.de/live Natalie Portman, fotografiert von Jim Rakete – zu sehen bei Hilaneh von Kories >> Seite 12 Ganz nah dran >> clubs & konzerte Seite 2–3 >> city & singles mit Restaurant-Tipps und Nina Georges Kolumne „Lieben Sie Hamburg?“ Seite 4–5 >> film Seite 6–11 >> kultur Seite 12–13 >> die woche Seite 14–16 >> vorverkauf Klassik/Rock, Pop, Jazz Seite 16 FOTOS: PHOTOSELECTION, LE ANN MUELLER, MALZKORN, TOBIS 2 clubs & konzerte 11. bis 17. März 2010 LIVE Klang-Unterwelt Der Wolf singt Rockabilly trifft auf Sex Hickey Underworld CCH: Kevin Costner Devil Doll röhrt am 15.3. im Knust „New International Music“, das Motto des Seine Zeit als Hollywood-Superstar liegt Und wieder tritt eine teuflische Pop-Puppe Reeperbahn-Festivals, passte letztes Jahr gut bereits ein paar Jahre zurück, attraktive ins Rampenlicht. Devil Doll, die bürgerlich zum Auftritt der belgischen Avantgarde- Drehbücher sind im Leben von Kevin Costner Colleen Duffy heißt, behauptet, sie habe ihr Postcore-Band The Hickey Underworld im seltener geworden. Vielleicht gibt er deshalb Musikprojekt an einem späten, verrauchten Kaiserkeller. Die Gruppe aus Antwerpen jetzt den singenden Cowboy. Angeblich hat Abend aus der Taufe gehoben. Mit Joan Jett zerstört auf dem selbst betitelten, von Das seine Frau ihn drei Jahre lang ermutigt, und Johnny Cash im Ohr beschloss sie, die Pop produzierten Album bekannte Strukturen endlich seiner heimlichen Passion nach- Mae West des Rockabilly zu werden. -

Documente Muzicale Tipărite Şi Audiovizuale

BIBLIOTECA NAŢIONALĂ A ROMÂNIEI BIBLIOGRAFIA NA ŢIONALĂ ROMÂNĂ Documente muzicale tipărite şi audiovizuale Bibliografie elaborată pe baza publicaţiilor din Depozitul Legal Anul XLVIII 2015 Editura Bibliotecii Naţionale a României BIBLIOGRAFIA NAŢIONALĂ ROMÂNĂ SERII ŞI PERIODICITATE Cărţi. Albume. Hărţi: bilunar Documente muzicale tipărite şi audiovizuale : anual Articole din publicaţii seriale. Cultură: lunar Publicaţii seriale: anual Românica: anual Teze de doctorat: semestrial © Copyright 2015 Toate drepturile sunt rezervate Editurii Bibliotecii Naţionale a României. Nicio parte din această lucrare nu poate fi reprodusă sub nicio formă, prin mijloc mecanic sau electronic sau stocat într-o bază de date, fără acordul prealabil, în scris, al redacţiei. Înlocuieşte seria Note muzicale. Discuri. Casete Redactor: Raluca Bucinschi Coperta: Constantin Aurelian Popovici Documente muzicale tipărite și audiovizuale 1 Cuprins COMPACT DISCURI ........................................................................................... 3 CD 1 - Literatură................................................................................................. 3 CD 1.1 Versuri ............................................................................................. 3 CD 1.3 Teatru ............................................................................................... 4 CD 1.4 Literatură pentru copii şi tineret....................................................... 7 CD 1.5 Alte genuri literare ..........................................................................