Etonia Creek/Cross Florida Greenway)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Everglades: Wetlands Not Wastelands Marjory Stoneman Douglas Overcoming the Barriers of Public Unawareness and the Profit Motive in South Florida

The Everglades: Wetlands not Wastelands Marjory Stoneman Douglas Overcoming the Barriers of Public Unawareness and the Profit Motive in South Florida Manav Bansal Senior Division Historical Paper Paper Length: 2,496 Bansal 1 "Marjory was the first voice to really wake a lot of us up to what we were doing to our quality of life. She was not just a pioneer of the environmental movement, she was a prophet, calling out to us to save the environment for our children and our grandchildren."1 - Florida Governor Lawton Chiles, 1991-1998 Introduction Marjory Stoneman Douglas was a vanguard in her ideas and approach to preserve the Florida Everglades. She not only convinced society that Florida’s wetlands were not wastelands, but also educated politicians that its value transcended profit. From the late 1800s, attempts were underway to drain large parts of the Everglades for economic gain.2 However, from the mid to late 20th century, Marjory Stoneman Douglas fought endlessly to bring widespread attention to the deteriorating Everglades and increase public awareness regarding its importance. To achieve this goal, Douglas broke societal, political, and economic barriers, all of which stemmed from the lack of familiarity with environmental conservation, apathy, and the near-sighted desire for immediate profit without consideration for the long-term impacts on Florida’s ecosystem. Using her voice as a catalyst for change, she fought to protect the Everglades from urban development and draining, two actions which would greatly impact the surrounding environment, wildlife, and ultimately help mitigate the effects of climate change. By educating the public and politicians, she served as a model for a new wave of environmental activism and she paved the way for the modern environmental movement. -

Kissimmee/Okeechobee Land Assessment Region: Kissimmee River

SFWMD Land Use Assessment 2013 Kissimmee River Rivers program acquired 49,000 acres in 290 land Polk, Osceola, Highlands, and Okeechobee Counties transactions to support the restoration of the river. Laboratory studies and field demonstrations were Area within planning boundary footprint conducted throughout the 1980s. A recommended plan ~ 116,317 acres was developed, and The Kissimmee River Restoration District fee-simple ownership and Project was authorized by Congress in the 1992 Water Right-of-Way fee interest Resources Development Act as a joint partnership between ~ 95,914 acres the District and the US Army Corps of Engineers. The Other public fee-simple ownership project was designed to restore over 40 square miles of ~ 1827 acres river/floodplain ecosystem including 43 miles of Area under other regulatory restriction meandering river channel and 27,000 acres of wetlands. To (conservation easement, platted preserve area, etc.) complete the restoration it was necessary to acquire ~ 1508 acres sufficient rights in the land within the 100-year floodplain. Site Overview Assessment Units Historically, the Kissimmee River meandered over 103 Pool A: KICCO and Blanket Bay miles within a one to two mile wide floodplain. The This area involved some of the earliest acquisitions for the floodplain, approximately 56 miles long, sloped gradually river. An early demonstration project to support the full to the south from an elevation of about 51 feet at Lake river restoration occurred over a portion of this site. Kissimmee to about 15 feet at Lake Okeechobee; falling an Kissimmee Prairie average of about 4 inches in elevation over each mile of The District acquired the parcels within the river the river. -

2020-FTA-Congressional-Report.Pdf

THE FLORIDA TRAIL ASSOCIATION Congressional Report 2020 117th Congress Florida National Scenic Trail Reroute in Development Side Trail Roadwalk Public Conservation Lands Federal Lands State & Local Lands Like on Facebook: facebook.com/floridatrailassociation Follow on Twitter: twitter.com/floridatrail See on Instagram: instagram.com/floridatrail Watch on Youtube: youtube.com/floridatrail Connect With Us Florida Trail Association Building More Than Trails 1050 NW 2nd St Gainesville, FL 32601 web: floridatrail.org email: [email protected] phone: 352-378-8823 The Florida Trail is Open To All The Florida Trail is a 1,500-mile footpath that extends from Big Cypress National Preserve at the edge of the Everglades in south Florida to Gulf Islands National Seashore on Santa Rosa Island in the Florida panhandle. Hike our white sand beaches. Travel through dense subtropical forests and vast, open grasslands. Test your physical and mental endurance in Florida’s swamps, marshes and wetlands. Encounter the diverse plant and animal life that flourish along the Florida Trail. The Florida Trail is non-partisan public resource that needs your support. Meet the Florida Trail Association The 90th US Congress passed the National Trail Systems Act in 1968. This Act authorized the creation of a national system of trails “to promote the preservation of, public access to, travel within, and enjoyment and appreciation of the open-air, outdoor areas and historic resources of the Nation.” It initially established the Appalachian Trail and Pacific Crest Trails. Today the National Trails System designates 11 National Scenic Trails, including the entirely unique Florida Trail. The Florida Trail is a National Scenic Trail spanning 1,500 miles from the Panhandle to the Everglades, offering year-round hiking for residents and visitors. -

Mike Roess Gold Head Branch State Park

Mike Roess Gold Head Branch State Park Unit Management Plan APPROVED STATE OF FLORIDA DEPARTMENT OF ENVIRONMENTAL PROTECTION Division of Recreation and Parks April 16, 2010 TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION............................................................................................................1 PURPOSE AND SIGNIFICANCE OF THE PARK ...................................................1 PURPOSE AND SCOPE OF THE PLAN.....................................................................4 MANAGEMENT PROGRAM OVERVIEW...............................................................5 Management Authority and Responsibility.............................................................5 Park Management Goals .............................................................................................6 Management Coordination.........................................................................................7 Public Participation......................................................................................................7 Other Designations......................................................................................................7 RESOURCE MANAGEMENT COMPONENT INTRODUCTION............................................................................................................9 RESOURCE DESCRIPTION AND ASSESSMENT................................................11 Natural Resources......................................................................................................11 Topography............................................................................................................11 -

EXTENSIONS of REMARKS March 5, 1992 EXTENSIONS of REMARKS

4666 EXTENSIONS OF REMARKS March 5, 1992 EXTENSIONS OF REMARKS A TRIBUTE TO THE LATE JEAN WHAT PRESIDENT BUSH SHOULD and economic reforms in Russia-has been YAWKEY DO AT THIS CRITICAL MOMENT virtually ignored. As a result, the United States and the West risk snatching defeat in the cold war from the jaws of victory. HON. JOHN JOSEPH MOAKLEY HON. WM.S.BROOMAELD We have heard repeatedly that the cold OF MASSACHUSETTS OF MICHIGAN war has ended and that the West won it. This IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES is only half true. The Communists have lost IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES the cold war, but the West has not yet won Thursday, March 5, 1992 Thursday, March 5, 1992 it. Communism collapsed because its ideas Mr. BROOMFIELD. Mr. Speaker, as Yogi failed. Today, the ideas of freedom are on Mr. MOAKLEY. Mr. Speaker, I rise today to trial. If they fail to produce a better life in pay tribute to the late Jean Yawkey who died Berra used to say: "It ain't over 'til it's over." In a few words, that's the import of a thought Russia and the other former Soviet repub of a stroke on February 27. For the past 59 ful commentary on the cold war that former lics, a new and more dangerous despotism years, Mrs. Yawkey has been the matriarch of will take power, with the people trading free President Richard Nixon sent to· me recently. the Boston Red Sox. Her involvement with the dom for security and entrusting their future President Nixon has been a leading figure in Sox began in 1933 when her husband Tom to old hands with new faces. -

X X United Way of Central Florida

United Way of Central Florida PO Box 1357 Highland City, FL 33846-1357 863-648-1500 uwcf.org 1 My Personal Information UWCF respects the privacy of our donors & does not disclose personal information to third parties Prefix: Name: Co. Name: Home Address: Division/Emp. ID #: City: State: Zip: Work Phone: -- Cell Phone: -- Date of Birth: // Preferred Email: 2 My Giving (Select one) 4 My Recognition (Optional) Option #1 Pledge: Payroll Deduction PLEASE LIST MY NAME AS IT APPEARS IN SECTION ONE OR AS FOLLOWS: I pledge the following each pay period: Preferred Recognition Name $20 $10 $5 $3 Other: I prefer that my gift remain anonymous Please combine my gift with my spouse X = Spouse Name $ Pay Periods My total annual gift: $ Option #2 Pledge: One-Time Gift Spouse’s Employer Check (Payable to United Way of Central Florida) My gift of $1000 or more qualifies me as a LEADERSHIP GIVER Cash My total annual gift: $ I would like to participate in the Young Leader’s Step-Up program. Please check one: $250 $500 $750 $1,000 (Minimum gift of $20) Option #3 Pledge: Direct Bill I am interested in learning more about other Leadership Step-up programs. Please bill me in the amount of Bill beginning (MM/YY): One-time Monthly Quarterly My Designation (Optional) My total annual gift: $ 5 Option #1: Community Investment Option #4 Pledge: Credit Card or Stock Transfer* The Best Investment. These funds improve lives with a focus on education, income, health and safety net. Over 120 volunteers on 18 *For credit card transactions or stock transfers, please Community Investment Teams distribute contributions according to our contact the United Way office at 863-648-1500. -

12 TOP BEACHES Amelia Island, Jacksonville & St

SUMMER 2014 THE COMPLETE GUIDE TO GO® First Coast ® wheretraveler.com 12 TOP BEACHES Amelia Island, Jacksonville & St. Augustine Plus: HANDS-ON, HISTORIC ATTRACTIONS SHOPPING, GOLF & DINING GUIDES JAXWM_1406SU_Cover.indd 1 5/30/14 2:17:15 PM JAXWM_1406SU_FullPages.indd 2 5/19/14 3:01:04 PM JAXWM_1406SU_FullPages.indd 1 5/19/14 2:59:15 PM First Coast Summer 2014 CONTENTS SEE MORE OF THE FIRST COAST AT WHERETRAVELER.COM The Plan The Guide Let’s get started The best of the First Coast SHOPPING 4 Editor’s Itinerary 28 From the scenic St. Johns River to the beautiful Atlantic Your guide to great, beaches, we share our tips local shopping, from for getting out on the water. Jacksonville’s St. Johns Avenue and San Marco Square to King Street in St. Augustine and Centre Street in Amelia Island. 6 Hot Dates Summer is a season of cel- ebrations, from fireworks to farmers markets and 32 MUSEUMS & concerts on the beach. ATTRACTIONS Tour Old Town St. 48 My First Coast Augustine in grand Cindy Stavely 10 style in your very own Meet the person behind horse-drawn carriage. St. Augustine’s Pirate Museum, Colonial Quarter 14 DINING & and First Colony. Where Now NIGHTLIFE 46..&3 5)&$0.1-&5&(6*%&50(0 First Coast ® Fresh shrimp just tastes like summer. Find out wheretraveler.com 9 Amelia Island 12 TO P BEACHES where to dig in and Amelia Island, Jacksonville & St. Augustine From the natural and the historic to the posh and get your hands dirty. luxurious, Amelia Island’s beaches off er something for every traveler. -

Species Status Assessment (SSA) Report for the Eastern Indigo Snake (Drymarchon Couperi) Version 1.1 July 8, 2019

Species Status Assessment (SSA) Report for the Eastern Indigo Snake (Drymarchon couperi) Version 1.1 July 8, 2019 Photo Credit: Dirk J. Stevenson U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Southeast Region Atlanta, GA ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The research for this document was prepared by Michele Elmore (U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) – Georgia Ecological Services), Linda LaClaire (USFWS – Mississippi Ecological Services), Mark Endries (USFWS - Asheville, North Carolina, Ecological Services), Michael Marshall (USFWS Region 4 Office), Stephanie DeMay (Texas A&M Natural Resources Institute), with technical assistance from Drew Becker and Erin Rivenbark (USFWS Region 4 Office). Valuable peer reviews of a draft of this report were provided by: Dr. David Breininger (Kennedy Space Center), Dr. Natalie Hyslop (North Georgia University), Dr. Chris Jenkins (The Orianne Society), Dirk Stevenson (Altamaha Environmental Consulting, LLC), John Jensen and Matt Elliot (Georgia Department of Natural Recourses) and multiple reviewers from the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission. Suggested reference: U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2019. Species status assessment report for the eastern indigo snake (Drymarchon couperi). Version 1.1, July, 2019. Atlanta, Georgia. Summary of Version Update The changes from version 1.0 (November 2018) to 1.1 (July 2019) are minor and do not change the SSA analysis for the eastern indigo snake. The changes were: 1) Various editorial corrections were made throughout the document. 2) Added clarifying information in Sections 2.4 and 5.1 regarding eastern indigo snake records. 3) Revised Sections 2.2 and 4.4 to include additional relevant references and restructured to clarify content. References updated throughout report including References section. -

Etoniah Creek State Forest Management Plan

TEN-YEAR RESOURCE MANAGEMENT PLAN FOR THE ETONIAH CREEK STATE FOREST PUTNAM COUNTY, FLORIDA PREPARED BY THE FLORIDA DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE AND CONSUMER SERVICES, FLORIDA FOREST SERVICE APPROVED ON JULY 9, 2015 Land Management Plan Compliance Checklist Etoniah Creek State Forest – April 2015 Section A: Acquisition Information Items Statute/ Page Numbers and/or Item # Requirement Rule Appendix 18-2.018 & Page 1 (Executive Summary); 1. The common name of the property. 18-2.021 Page 2 (I); Page 9 (II.A.1) Page 1 (Executive Summary); The land acquisition program, if any, under which the property 18-2.018 & 2. Page 2 (I); Page 10 (II.A.4); was acquired. 18-2.021 Page 10 (II.B.1) Degree of title interest held by the Board, including 3. 18-2.021 Page 11 (II.B.2) reservations and encumbrances such as leases. 18-2.018 & 4. The legal description and acreage of the property. Page 9 (II.A.2) 18-2.021 A map showing the approximate location and boundaries of 18-2.018 & 5. the property, and the location of any structures or Exhibits B, C, and E 18-2.021 improvements to the property. An assessment as to whether the property, or any portion, 6. 18-2.021 Page 15 (II.D.3) should be declared surplus. Identification of other parcels of land within or immediately Page 14 (II.D.2); 7. adjacent to the property that should be purchased because they 18-2.021 are essential to management of the property. Exhibit F Identification of adjacent land uses that conflict with the 8. -

X United Way of Central Florida

United Way of Central Florida PO Box 1357 Highland City, FL 33846-1357 863-648-1500 uwcf.org 1 My Personal Information UWCF respects the privacy of our donors & does not disclose personal information to third parties Prefix: Name: Co. Name: Home Address: Division/Emp. ID #: City: State: Zip: Work Phone: -- Cell Phone: -- Date of Birth: // Preferred Email: My Giving (Select one) 3 My Recognition (Optional) 2 PLEASE LIST MY NAME AS IT APPEARS IN SECTION ONE OR AS FOLLOWS: Option #1 Pledge: Payroll Deduction I pledge the following each pay period: Preferred Recognition Name $20 $10 $5 $3 Other: I prefer that my gift remain anonymous Please combine my gift with my spouse X = Spouse Name $ Pay Periods My total annual gift: $ Spouse’s Employer Option #2 Pledge: One-Time Gift My gift of $1000 or more qualifies me as a LEADERSHIP GIVER Check (Payable to United Way of Central Florida) I would like to participate in the Young Leader’s Step-Up program. Cash My total annual gift: $ Please check one: $250 $500 $750 $1,000 I am interested in learning more about other Leadership Step-up programs. Option #3 Pledge: Direct Bill (Minimum gift of $20) Please bill me in the amount of Bill beginning (MM/YY): My Designation (Optional) One-time Monthly Quarterly 4 Option #1: Community Investment My total annual gift: $ The Best Investment. These funds improve lives with a focus on education, income, health and safety net. Over 120 volunteers on 17 Community Investment Teams distribute contributions according to our Option #4 Pledge: Credit Card or Stock Transfer* community’s most critical needs. -

Membership List for Website 8-6-20

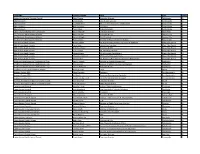

COMPANY CONTACT NAME TITLE CITY STATE Apalachee Regional Planning Council Chris Rietow Executive Director Tallahassee FL Babcock Ranch Erika Woods SVP of Legal Services Punta Gorda FL Babcock Ranch Lucienne Pears VP Economic & Business Development Punta Gorda FL Babcock Ranch Rick Severance President Punta Gorda FL Babcock Ranch Tyler Kitson Project Manager Punta Gorda FL Baker County Development Commission Darryl Register Executive Director Macclenny FL Bay Economic Development Alliance Becca Harden President & CEO Panama City FL Bay Economic Development Alliance Garrett Wright Vice President Panama City FL Bay Economic Development Alliance Polly Jackson Director of Finance & Administration Panama City FL BDB of Palm Beach County Brian Cartland VP Business Recruitment, Expansion & Retention West Palm Beach FL BDB of Palm Beach County Gary Hines Senior Vice President West Palm Beach FL BDB of Palm Beach County Kelly Smallridge President & CEO West Palm Beach FL BDB of Palm Beach County Luke Jackson VP, The Glades Region West Palm Beach FL BDB of Palm Beach County Shawn Rowan VP of Business Recruitment West Palm Beach FL BDB of Palm Beach County Shereena Coleman VP Business Existing Industry West Palm Beach FL BDB of Palm Beach County Tim Dougher VP, Businesss Recruitment, Retention & Expansion West Palm Beach FL Bradenton Area Economic Development Corp. Lauren Kratsch Director of Project Management Bradenton FL Bradenton Area Economic Development Corp. Max Stewart Director of Global Business Development Bradenton FL Bradenton Area Economic -

Enterprise Florida Annual Report FY 2011-2012 Photo: Nasaphoto

Enterprise Florida Annual Report FY 2011-2012 Photo: NASAPhoto: Enterprise Florida is the lead economic development organization for the state of Florida. Rick Scott, Governor Chairman, Enterprise Florida, Inc. “Florida is receiving a lot of attention from companies that want to move to our business-friendly climate as well as from current in-state companies desiring to expand here. The reason is that we’ve lowered business taxes and are eliminating regulations that restrict the ability to grow. Enterprise Florida works hard to capitalize on this interest. What also helps is that Florida’s economy is strengthening: unemployment is down, tourism is up, exports are up, home prices are up, home sales are up, and new home construction is up. My administration and Enterprise Florida look forward to bringing more job opportunities to all our citizens.” Howell W. Melton Vice Chairman, Enterprise Florida, Inc. “Creating jobs to get citizens back to work is one of the most important issues Florida faces. Enterprise Florida facilitated the creation of 25,339 jobs through competitive projects this past year, but we still have a lot of work to do. The more jobs we create, there’s less dependence on state services, private investment flourishes, entrepreneurship expedites and the state’s overall standard of living improves.” Gray Swoope, Secretary of Commerce President & CEO, Enterprise Florida, Inc. “This past year, our team succeeded in building the strong economic development partnerships needed to identify and win more competitive projects, strengthen international trade and sports development programs, and make it easier to do business in Florida. Our mission is to build on these results to elevate Florida’s economy into the most vibrant in the nation.” Enterprise Florida Senior Staff Gray Swoope Griff Salmon Melissa Medley John Webb Secretary of Commerce Executive Vice President Senior Vice President President President & CEO, & COO & CMO Florida Sports Foundation Enterprise Florida, Inc.