Framework Framework 56.1 | Spring 2015 Framework

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Come Back Africa Press Kit.Pdf

MILESTONE FILM • PO Box 128 • Harrington Park, NJ 07640 Phone: (201) 767-3117 • [email protected] • www.comebackafrica.com Come Back, Africa Crew Produced and Directed by Lionel Rogosin Written by Lionel Rogosin with Lewis Nkosi and William Modisane Photographed by Ernst Artaria and Emil Knebel Sound Walter Wettler Edited by Carl Lerner Assistant Editor Hugh H. Robertson Music Editor Lucy Brown South African consultant Boris Sackville Clapper loader/production/sets Morris Hugh Production staff Elinor Hart, Morris Hugh, George Malebye Featuring the music of Chatur Lal Cast Featuring the People of Johannesburg, South Africa Rams Zacharia Mgabi and Vinah Bendile Steven Arnold Hazel Futa Auntie (Martha – Shebeen queen) Lewis Nkosi Dube-Dube Bloke Modisane Eddy Can Themba George Malebye Piet Beyleveld Marumu Ian Hoogendyk Miriam Makeba Alexander Sackville Morris Hugh Sarah Sackville Myrtle Berman This film was made secretly in order to portray the true conditions of life in South Africa today. There are no professional actors in this drama of the fate of a man and his country. This is the story of Zachariah – one of the hundreds of thousands of Africans forced each year off the land by the regime and into the gold mines. From Come Back, Africa ©1959 Lionel Rogosin Films Premiered at the 1959 Venice Film Festival. 2 Theatrical Release date: April 4, 1960. Running time: 86 minutes. B&W. Mono. Country: South Africa/United States. Language: English, Afrikaans and Zulu. Restored by the Cineteca di Bologna and the laboratory L’Imagine Ritrovata with the collaboration of Rogosin Heritage and the Anthology Film Archives in 2005. -

Minetta Tavern 113 Macdougal St., New York, NY 10012 (Btw

Café Wha?/The Players Theatre 115 Macdougal, between Bleecker and W 3rd, New York, NY -Minetta Lane 6 - 8 “Since the 1950s the Café Wha? has been a favorite hot spot cornered in the heart of Greenwich Village. The 60s was an impressionable and revolutionary era. Artists of the time frequented the Café Wha? as it was known to be a sanctuary for talent; Allen Ginsberg regularly sipped his cocktails here. The Café Wha? was the original stomping ground for prodigies Bob Dylan and Jimi Hendrix. Bruce Springsteen, Peter, Paul & Mary, Kool and the Gang, as well as comedians, Richard Pryor and Bill Cosby also began their road to stardom on this historic stage. The Café Wha? encompassed the Beat Generation and continues to hold tight to its spirit, entertaining all walks of life. Today, the Café Wha? showcases amazing talent with the three greatest house bands in New York City. Monday nights feature Brazooka, a completely authentic Brazilian dance band sprinkled with Jazz and Samba. Disfunktiontakes on Tuesdays with soul music, radiating the roots of R&B and Funk. What about the Café Wha? House Band? Wednesday thru Sunday they will satisfy your every need for sound, hitting on all styles of music; Motown, Reggae, R&B, and Classic/ Alternative/ Modern rock. Every night at the Café Wha? is a party. You never know which famous musician will show up and sit in with one of these incredible bands. The New York Times raves, “Power house talent - you'd be hard-pressed to find a more exhilarating evening out." The Café Wha? is a stop you have to make whether you are living or just visiting New York City.” “Built in 1907 and converted into a theatre in the late 1940's, the Players Theatre has been a jewel in the midst of beautiful Greenwich Village, serving as a magnet for performing artists and their audiences. -

National Register of Historic Places Registration Form

NPS Form 10-900 OMB No. 10024-0018 (Oct. 1990) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and districts. See instructions in How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form (National Register Bulletin 16A). Complete each item by marking “x” in the appropriate box or by entering the information requested. If an item does not apply to the property being documented, enter “N/A” for “not applicable.” For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. Place additional entries and narrative items on continuation sheets (NPS Form 10-900a). Use a typewriter, word processor, or computer to complete all items. 1. Name of Property historic name South Village Historic District other names/site number N/A 2. Location street & number Bedford St., Bleecker St., Broome St., Carmine St., Clarkson St., Cornelia St., Downing St., Grand St., Jones St., LaGuardia Pl., Leroy St., MacDougal St., Minetta Ln., Morton St., Prince St., St. Luke’s Pl., Seventh Ave, Sixth Ave., Spring St., Sullivan St., Thompson St., Varick St., Washington Sq. So., Watts St., West 3rd St, West 4th St., W. Houston St. [ ] not for publication city or town Manhattan [ ] vicinity state New York code NY county New York code 061 zip code 10012 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act, as amended, I hereby certify that this [X] nomination [ ] request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements as set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. -

The South Village: a Proposal for Historic District Designation by Andrew S

TThhee SSoouutthh VViillllaaggee:: A Proposal for Historic District Designation Report by Andrew S. Dolkart Commissioned by the Greenwich Village Society for Historic Preservation 232 East 11th Street, New York, NY 10003 212-475-9585 www.gvshp.org Report funded by Preserve New York, a grant program of the Preservation League of New York State and the New York State Council on the Arts Greenwich Village Society for Historic Preservation 232 East 11th Street, New York, NY 10003 212-475-9585 212-475-9582 Fax www.gvshp.org [email protected] Board of Trustees: Mary Ann Arisman, President Arthur Levin, Vice President Linda Yowell, Vice President Katherine Schoonover, Secretary/Treasurer Penelope Bareau Meredith Bergmann Elizabeth Ely Jo Hamilton Leslie Mason Ruth McCoy Florent Morellet Peter Mullan Andrew S. Paul Jonathan Russo Judith Stonehill Arbie Thalacker George Vellonakis Fred Wistow F. Anthony Zunino III Staff: Andrew Berman, Executive Director Melissa Baldock, Director of Preservation and Research Sheryl Woodruff, Director of Operations Drew Durniak, Office Manager & Administrative Director TThhee SSoouutthh VViillllaaggee:: A Proposal for Historic District Designation Report by Andrew S. Dolkart Commissioned by the Greenwich Village Society for Historic Preservation Report funded by Preserve New York, a grant program of the Preservation League of New York State and the New York State Council on the Arts © The Greenwich Village Society for Historic Preservation, 2006. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The Greenwich Village Society for Historic Preservation would like to thank Preserve New York, a grant program of the Preservation League of New York State and the New York State Council on the Arts, for funding this report. -

Violence in NYC Against People of Color, Women, Lesbians

.':IF ~ HOMOSEXUALS DRAG QUEENS LESBIANS tJhe QUEER NATION CRuQe~ af[~ ! Chip Duckett presents MARS NEEDS MEN • Sunday Nights at Mars Drinking • Dancing • Go-Go Boys • Drag Queens • Live Bands OJ's Michael Connolly, Larry Tee, Perfidia & John Suliga • from 9pm DYKES QUEERBOVS AND YOUI AIDS Treatment News Uames) 32 Art Painters: At TheEnd Of A Decade 54 Theater Dig, Volley, Spike! 56 Theater Travesties 57 Theater Lisoon Traviata 58 Books TheIrreversible Decline Of EddieSoc~t On the cover: Monika Treut 59 photographed by Mark Golebiowski Books War At Home 60 Outspoken (Editorial) 4 Letters 6 Sotomayor 6 PAIN AND PI.FASOIE Stonewall Rioo (Natalie) 8 Catherine Saalfield Interviews German Filmmaker Monika Treut 40 Xeroxed 9 Nightrmre of the Week 9 SEEING mE UGIIT Dykes To Watch Out For 10 Mark Chesnut On Lavender Light: The Black and People of All Colors Lesbian and Gay Gospel Choir 44 Anaheim Journal (Krastins) 34 New York Journal (Wieder) 36 Out Of Control (Day) 38 Lookout 46 Out Of My Hands (BaJJ) 48 Gossip Watch 49 Social Terrorism 50 Going Out Calendar (X) 62 Community Directory 64 Bar Guide 66 FAWNG INTO THE GAP Classifieds 69 Beauregard Houston-Montgomery Spots the Visible Differences on St. Marks And Other Places 52 Personals 76 Crossword (Greco) 90 The High Cost of Charity In a recent column, gossipist James Revson of Newsday, who is gay, attacked writers in OUtWeek and the Village Voice for criticizing Mrs. William F. Buckley, Jr. Mrs. Bl!ckley is the wife of one of the nation's chief homo- phobes, a man who has publicly called for the tatooing and inqu-ceration of PWAs and who rants and rails in the press a~ut AIDS being a "self-inflicted" disease. -

Former Attorneys Take Croman to Court

The Voice of the West Village WestView News VOLUME 11, NUMBER 8 AUGUST 2015 $1.00 My Arrest. It Wasn’t Fair Former Attorneys and It Wasn’t Fun. Take Croman to Court: By Arthur Z. Schwartz experienced the searing humiliation of eyes asking “what crime did that man commit.” The Game of Tactics And the humiliation continued when police By Tres Kelvin escorted him into the Criminal Court where he had brought dozens of clients. Now he Greed Bites the Hand That was the criminal. Lawyers and even a few Steals for It judges who recognized him looked surprised The hand-cuffed arrest and and stunned—“why was attorney Arthur subsequent arraignment in Schwartz in handcuffs, what did he do?” Criminal Court of activist Arthur Schwartz had acted because an attorney Arthur Schwartz amoral landlord who contrived to get a and the false anonymous call ninety-two-year-old tenant committed to a to the health department that nursing home and then installed surveillance raw sewerage was contami- cameras had simply gone too far. Schwartz nating the kitchen of Nelly’s removed the cameras—and became a victim restaurant, Lima’s Taste are FIGHTING ATTORNEY ARRESTED: Arthur of those who can afford and relish the abuse just two of many actions Schwartz after his arrest looks at the article in of law. —George Capsis taken by two different West $790 or $2,360—THE HALF MILLION DOLLAR “MISTAKE”: WestView News that started it all—the event Village landlords. These Nelida Godfrey stands at the entrance of her apartment also made the Times, the Post, Daily News Since Ruth Berk got home, I have dedi- landlords use city regulations after winning a court decision. -

Digital Projection in Repertory Theatres

“This is DCP”: Digital Projection in Repertory Theatres Shira Peltzman & Casey Scott Culture of Archives, Museums, and Libraries CINE-GT 3049-001 Antonia Lant Peltzman & Scott Table of Contents Introduction ..................................................................................................................................... 2 History of Repertory Cinemas in New York City .......................................................................... 3 Repertory Cinemas in New York City in the 1960s and 1970s ...................................................... 4 Changes in Repertory Cinemas in New York from the 1980s to Today ........................................ 9 Repertory Cinemas as Museums ................................................................................................... 14 The Roots of Digital Cinema: “Visualizing the Invisible” ........................................................... 16 The Roots of Digital Cinema: Charge-Coupled Devices .............................................................. 19 The Advent of Digital Video ........................................................................................................ 21 Digital Cinema and George Lucas ................................................................................................ 22 Digital Cinema Standards ............................................................................................................. 24 Digital Cinema Packages ............................................................................................................. -

The Cheapskates by Jerome Sala

BONE BOUQUET 2 DOUBLECROSS PRESS 3 LOUFFA PRESS 4 LUNAR CHANDELIER PRESS 5 6 Aliperti THE OPERATING SYSTEM BOOG CITY 7 A COMMUNITY NEWSPAPER FROM ArcuniA GROUP OF ARTISTS AND WRITERS BASED IN AND AROUND NEW YORK CITY’S EAST VILLAGE ISSUE 94 FREE WE’LL NEVER HAVE PARIS Chappell Core Dravec Bone Bouquet Elan CelebrateFagin Six of the City’s Best Small Presses Fairhurst Goldstein Hong InsideKocher in Their Own Words and Live Miller Rodriguez Rothenbeck Scrupe Wallschlaeger Wheeler Wolfe Zighelboim Bone Bouquet Issue 5.1 Spring 2014 Issue 5.1 cover design by Jana Vukovic Readings from Bone Bou- d.a. levy lives quet, DoubleCross Press, Louffa Press, Lunar Chan- celebrating renegade presses delier Press, The Oper- ating System, and We’ll NYC Small Presses Night Never Have Paris authors Thurs. Nov. 20, 6:00 p.m., $5 suggested (see below). Bone Bouquet Louffa Press The Operating System Sidewalk Cafe —Samantha —Erika Anderson —Lynne DeSilva-Johnson 5:30 p.m. 94 Avenue A (@ E. 6th St.) Zighelboim —David Moscovich —JP Howard The East Village —Dustin Luke Nelson For information call DoubleCross Press We’ll Never Have Paris Book 212-842-BOOG (2664) —Ian Dreiblatt Lunar Chandelier Press —Veronica Liu [email protected] —Anna —Joe Elliot @boogcity with music from http://www.boogcity.com/ Gurton-Wachter —Jerome Sala Fair Yeti boogpdfs/bc94.pdf 2 BOOG CITY WWW.BOOGCITY.COM NEW ALL-LETTERPRESS POETICS OF THE CHAPBOOK SERIES HANDMADE SERIES In 2015, DoubleCross Press will be publishing DoubleCross Press’s Poetics of the Hand- a series of tiny poetry manuscripts (7 pages or made series publishes essays by contemporary less) for a new all-letterpress chapbook series. -

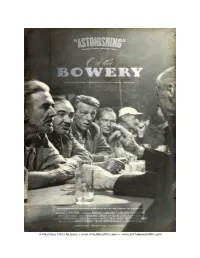

Here a Group of Drunks Are Arguing Loudly

A Milestone Films Release • www.milestonefilms.com • www.ontheboweryfilm.com A Milestone Films release ON THE BOWERY 1956. USA. 65 minutes. 35mm. Aspect ratio: 1:1.33. Black and White. Mono. World Premiere: 1956, Venice Film Festival Selected in 2008 for the National Film Registry by the Library of Congress Winner of the Grand Prize in Documentary & Short Film Category, Venice Film Festival, 1956. British Film Academy Award, “The Best Documentary of 1956.” British Film Festival, 1957. Nominated for American Academy Award, Best Documentary, 1958. A Milestone Films theatrical release: October 2010. ©1956 Lionel Rogosin Productions, Inc. All rights reserved. The restoration of On the Bowery has been encouraged by Rogosin Heritage Inc. and carried out by Cineteca del Comune di Bologna. The restoration is based on the original negatives preserved at the Anthology Film Archives in New York City. The restoration was carried out at L’Immagine Ritrovata laboratory. The Men of On the Bowery Ray Salyer Gorman Hendricks Frank Matthews Dedicated to: Gorman Hendricks Crew: Produced & Directed by .............Lionel Rogosin In collaboration with ...................Richard Bagley and Mark Sufrin Technical Staff ............................Newton Avrutis, Darwin Deen, Lucy Sabsay, Greg Zilboorg Jr., Martin Garcia Edited by ......................................Carl Lerner Music............................................Charles Mills Conducted by...............................Harold Gomberg The Perfect Team: The Making of On The Bowery 2009. France/USA/Italy. 46:30 minutes. Digital. Aspect Ratio: 1:1.85. Color/B&W. Stereo. Produced and directed by Michael Rogosin. Rogosin interviews by Marina Goldovskaya. Edited by Thierry Simonnet. Assistant Editor: Céleste Rogosin. Cinematography and sound by Zach Levy, Michael Rogosin, Lloyd Ross. Research and archiving: Matt Peterson. -

2013-2014 Annual Report Greenwich Village Preserving Society for Our Past, Historic Preservation

GREENWICH VILLAGE SOCIETY FOR HISTORIC PRESERVATION 2013-2014 ANNUAL REPORT GREENWICH VILLAGE PRESERVING SOCIETY FOR OUR PAST, HISTORIC PRESERVATION Trustees 2013–2014 ENGAGING President Arthur Levin Mary Ann Arisman Cynthia Penney Penelope Bareau Rob Rogers Vice Presidents Tom Birchard Katherine Schoonover OUR Leslie Mason Elizabeth Ely Marilyn Sobel Kate Bostock Shefferman Cassie Glover Judith Stonehill Justine Leguizamo Fred Wistow Secretary/Treasurer Ruth McCoy Linda Yowell FUTURE. Allan Sperling Andrew Paul F. Anthony Zunino, III GVSHP Staff Executive Director Director of Administration Program and Andrew Berman Drew Durniak Administrative Associate Ted Mineau Director of Preservation East Village and Special and Research Projects Director Senior Director of Operations Amanda Davis Karen Loew Sheryl Woodruff Offices Greenwich Village Society for Historic Preservation 232 East 11th Street, New York, NY 10003 T: 212-475-9585 | F: 212-475-9582 | www.gvshp.org Support GVSHP – become a member or make a donation: gvshp.org/membership Join our e-mail list for alerts and updates: [email protected] Visit our blog Off the Grid (gvshp.org/blog) Connect with GVSHP: Facebook.com/gvshp Twitter.com/gvshp YouTube.com/gvshp Flickr.com/gvshp 3 A NOTE FROM THE PRESIDENT I am pleased to report that the Society has seen We reviewed, publicized, and responded to more than one hundred applications for changes to great success with its programs over the last year, landmarked properties in our neighborhoods, advocating always for preserving the human scale, and is in a strong position to face the challenges sensitive design, and varied detailing which define our neighborhoods. presented by a new City administration and an SANDY HECHTMAN SANDY increasingly aggressive real estate lobby. -

VILLAGE PRESERVATION ORAL HISTORY PROJECT Oral History

VILLAGE PRESERVATION ORAL HISTORY PROJECT Oral History Interview ROB MASON By Sarah Dziedzic New York, NY May 13, 2020 Oral History Interview with Rob Mason, May 13, 2020 Narrator(s) Robert Paul Mason Address 12 E 12th Street, NY, NY Birthyear 1946 Birthplace - Narrator Age 74 Interviewer Sarah Dziedzic Place of Interview virtual Date of Interview May 13, 2020 Duration of Interview 144 mins Number of Sessions 1 Waiver Signed/copy given Y Photographs Y Format Recorded .wav 44kHz/16bit Mason_RobGVSHPOralHistory_archiv Archival File Names al.wav [1.43 GB] Mason_RobGVSHPOralHistory_zooma MP3 File Name udio+redactions.mp3 [113.6 MB] Order in Oral Histories 43 [#1 2020] Mason–ii Robert Mason, 2018 (Taormina, Italy), Photo by Mary Jan Mason Mason–iii Quotes from Oral History Interview with Rob Mason Sound-bite “My name is Robert Mason. I’ve been in the music and recording field since a very early age. …I was synthesizing my formal training with what I was acquiring through osmosis by being exposed to the master practitioners themselves while they were actually practicing their art. That combination was ineffable. One just absorbs it all and becomes a part of the culture and the culture becomes a part of you. It was very helpful in building an early sense of confidence that came in handy later on because I really felt like I belonged almost no matter where I was.” *** Additional Quotes “…my dad would regularly take me to the Village Vanguard, starting when I was around eight years old, for Sunday afternoon matinees. That was when I was first introduced to the live music field. -

A Conversation with Jackie Raynal

FILMS UNDER DISCUSSION / INTERVIEWS · Cinema Comparat/ive Cinema · Vol. I · No. 2. · 2013 · 29-41 A conversation with Jackie Raynal Pierre Léon (in collaboration with Fernando Ganzo) ABSTRACT This conversation between two film-makers belonging navigates the progressive changes of cinema as lived by Jackie Raynal since the 1960s (her education, Langlois’s programmes, her experience Turing the period of radicalisation, the so-called ‘critical generation’, the creation and development of the Group Zanzibar, collective forms of working), which are set in relationship to the experience of Pierre Léon since the 1980s. In addition, Raynal and Léon discuss the work of film-makers such as Jean Rouch or Mario Ruspoli and the relationship of ‘direct cinema’ to New American Cinema, the link Renoir-Rohmer, the transformation of ‘language’ in ‘idiom’ in relationship to classical cinema and its reception at the time, feminism and the reaction to Deus foix, collectives’ such as Medvedkine or Cinélutte vs. Zanzibar, the differences between the New York underground (Warhol, Jacobs, Malanga) and the French one (Deval, Arrietta, Bard) and, finally, the work of Raynal as film programmer alter leaving Paris and the Zanzibar Group, at the Bleecker St. Cinema, tackling issues such as the evolution of the audience in that venue, the different positions of American and French criticism, the programmes ‘Rivette in Context’ (Rosenbaum) and ‘New French Cinema’ (Daney and Skorecki) or the differences in the role of the ‘passeur’ of the critic and the programmer. KEYWORDS “Critical generation”, Langlois, programming, Group Zanzibar, collective forms of working, underground, aesthetic radicalization, evolution of the audience, Andy Warhol, Jean Rouch.