Doulamas” the Magnificent

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

End of Term Press Release

END OF TERM PRESS RELEASE The Epidaurus Lyceum - International Summer School of Ancient Drama successfully completed its inaugural year on 19 July. The programme was realised under the auspices and support of the Hellenic Ministry of Culture and Sports, in collaboration with the Department of Theatre Studies, School of Fine Arts, University of the Peloponnese and the support of the Municipality of Epidaurus. A brand-new educational institution operating under the Athens & Epidaurus Festival, the Lyceum welcomed 120 students of drama schools and theatre studies university departments, as well as young actors from around the world for its first annual theme “The Arrival of the Outsider.” The Epidaurus Lyceum students attended a main five-hour practical workshop daily. In 2017, the teaching staff of the Lyceum for practical workshops consisted of the following: Phillip Zarrilli, a celebrated director, performer, and teacher of a technique for actors combining yoga and Asian martial arts; Simon Abkarian and Catherine Schaub Abkarian, core members of Ariane Mnouchkine’s legendary Théâtre du Soleil; Rosalba Torres Guerrero, one of the core members of Anne Teresa De Keersmaeker’s Rosas dance group, along with dancer and choreographer Koen Augustijnen; Enrico Bonavera, actor and drama teacher, who has worked closely with Milan’s Piccolo Teatro; RootlessRoot, an ever-active dance company who has created the “Fighting Monkey” programme; Greek directors Martha Frintzila, Simos Kakalas, Sotiris Karamesinis, Kostantinos Ntellas, actress Rinio Kyriazi, and others. The 2017 programme of studies consisted of theory workshops, lectures, and masterclasses, in accordance to this year’s overarching theme. The majority of these events were open to the public, in an effort to strengthen the Lyceum’s ties to the local community. -

200Th Anniversary of the Greek War of Independence 1821-2021 18 1821-2021

Special Edition: 200th Anniversary of the Greek War of Independence 1821-2021 18 1821-2021 A publication of the Dean C. and Zoë S. Pappas Interdisciplinary March 2021 VOLUME 1 ISSUE NO. 3 Center for Hellenic Studies and the Friends of Hellenic Studies From the Director Dear Friends, On March 25, 1821, in the city of Kalamata in the southern Peloponnesos, the chieftains from the region of Mani convened the Messinian Senate of Kalamata to issue a revolutionary proclamation for “Liberty.” The commander Petrobey Mavromichalis then wrote the following appeal to the Americans: “Citizens of the United States of America!…Having formed the resolution to live or die for freedom, we are drawn toward you by a just sympathy; since it is in your land that Liberty has fixed her abode, and by you that she is prized as by our fathers.” He added, “It is for you, citizens of America, to crown this glory, in aiding us to purge Greece from the barbarians, who for four hundred years have polluted the soil.” The Greek revolutionaries understood themselves as part of a universal struggle for freedom. It is this universal struggle for freedom that the Pappas Center for Hellenic Studies and Stockton University raises up and celebrates on the occasion of the 200th anniversary of the beginning of the Greek Revolution in 1821. The Pappas Center IN THIS ISSUE for Hellenic Studies and the Friends of Hellenic Studies have prepared this Special Edition of the Hellenic Voice for you to enjoy. In this Special Edition, we feature the Pappas Center exhibition, The Greek Pg. -

“The Semiotics of the Imagery of the Greek War of Independence. from Delacroix to the Frieze in Otto’S Palace, the Current Hellenic Parliament”

American Research Journal of Humanities & Social Science (ARJHSS)R) 2020 American Research Journal of Humanities & Social Science (ARJHSS) E-ISSN: 2378-702X Volume-03, Issue-01, pp 36-41 January-2020 www.arjhss.com Research Paper Open Access “The Semiotics of the Imagery of the Greek War of Independence. From Delacroix to the Frieze in Otto’s Palace, The Current Hellenic Parliament”. Markella-Elpida Tsichla University of Patras *Corresponding Author: Markella-Elpida Tsichla ABSTRACT:- The iconography of the Greek War of Independence is quite broad and it includes both real and imaginary themes. Artists who were inspired by this particular and extremely important historical event originated from a variety of countries, some were already well-known, such as Eugène Delacroix, others were executing official commissions from kings of Western countries, and most of them were driven by the spirit of romanticism. This paper shall not so much focus on matters of art criticism, but rather explore the manner in which facts have been represented in specific works of art, referring to political, religious and cultural issues, which are still relevant to this day. In particular, I shall comment on The Massacre at Chios by Eugène Delacroix, painted in 1824, the 39 Scenes from the Greek War of Independence by Peter von Hess, painted in 1835 and commissioned by King Ludwig I of Bavaria, and the frieze in the Trophy Room (currently Eleftherios Venizelos Hall) in Otto’s palace in Athens, currently housing the Hellenic Parliament, themed around the Greek War of Independence and the subsequent events. This great work was designed by German sculptor Ludwig Michael Schantahaler in 1840 and “transferred” to the walls of the hall by a group of Greek and German artists. -

The Political Economy of King's Otto Reign

Tafter Journal scritto da George Tridimas il 15 Luglio 2017 When the Greeks Loved the Germans: The Political Economy of King’s Otto Reign This article has been first published on German-Greek Yearbook of Political Economy, vol. 1 (2017) [1] Abstract In 1832 Prince Otto Wittelsbach of Bavaria was appointed King of the newly founded independent Greek state. Otto’s reign was a momentous period for Greece, initially under Regency then under Otto as an absolute ruler and from 1843 as a constitutional monarch until his expulsion in 1862. Using the historical record the paper focuses on three political economy questions, namely, the rationale for the foundation of a state, which relates to the provision of public goods and rent distribution, the constitutional order of the state regarding the choice between monarchy or republic, and the emergence of democracy by revolution or evolution. Introduction An aspect of the ongoing multifaceted Greek debt crisis has been a strain in the relations between Greece and Germany, where members of the German cabinet have been caricatured as heartless fiscal disciplinarians and of the Greek cabinet as delinquent fiscal rule breakers. A moment’s calmer reflection reminds us that in modern times the relations between Greece and Germany have been long standing and steeped in mutual respect. A case in point is the reign of King Otto of Greece from the Bavarian royal house of Wittelsbach. Modern Greece rose formally as an independent nation state in 1832 with the seventeen year old Otto as its ruler. Otto was welcomed in Greece with jubilation. -

«Τα Εργα Των Ιταλων Ζωγραφων Lipparini Kai Marsigli Στα

ΑΡΙΣΤΟΤΕΛΕΙΟ ΠΑΝΕΠΙΣΤΗΜΙΟ ΘΕΣΣΑΛΟΝΙΚΗΣ ΦΙΛΟΣΟΦΙΚΗ ΣΧΟΛΗ ΤΜΗΜΑ ΙΤΑΛΙΚΗΣ ΓΛΩΣΣΑΣ ΚΑΙ ΦΙΛΟΛΟΓΙΑΣ ΠΡΟΓΡΑΜΜΑ ΜΕΤΑΠΤΥΧΙΑΚΩΝ ΣΠΟΥΔΩΝ ΚΑΤΕΥΘΥΝΣΗ ΛΟΓΟΤΕΧΝΙΑ ΚΑΙ ΠΟΛΙΤΙΣΜΟΣ «ΤΑ ΕΡΓΑ ΤΩΝ ΙΤΑΛΩΝ ΖΩΓΡΑΦΩΝ LIPPARINI KAI MARSIGLI ΣΤΑ ΠΛΑΙΣΙΑ ΤΟΥ ΕΥΡΩΠΑΙΚΟΥ ΦΙΛΕΛΛΗΝΙΣΜΟΥ ΚΑΤΑ ΤΗΝ ΕΠΑΝΑΣΤΑΣΗ ΤΟΥ 1821» ΜΕΤΑΠΤΥΧΙΑΚΗ ΕΡΓΑΣΙΑ Στυλιανής Α. Μπίκα A.E.M. 12 ΕΠΙΒΛΕΠΟΥΣΑ: Ε. ΜΕΛΕΖΙΑΔΟΥ - ΔΟΜΠΟΥΛΑ Τριμελής Επιτροπή: E. Μελεζιάδου-Δομπούλα Eπίκουρη καθηγήτρια Α.Π.Θ. Β.Κ. Ιβάνοβιτς Αναπληρωτής καθηγητής Α.Π.Θ. G. Macrì Αναπληρώτρια καθηγήτρια Α.Π.Θ. ΘΕΣΣΑΛΟΝΙΚΗ 2012 0 Στην Άννα, στον Αλέξιο και στο Δανιήλ 1 ΠΙΝΑΚΑΣ ΠΕΡΙΕΧΟΜΕΝΩΝ 1.Εισαγωγή σ. 4 2.Ο Ευρωπαϊκός φιλελληνισμός σ. 6 3.Ο φιλελληνισμός και η Ελληνική επανάσταση σ. 7 4.Οι πρώτες φιλελληνικές εκδηλώσεις σ. 9 5.Η φιλελληνική δραστηριότητα στη Γερμανία σ. 12 6.Ο φιλελληνισμός στη Γαλλία & η ίδρυση της πρώτης φιλελληνικής επιτροπής σ. 14 7.Η φιλελληνική κίνηση στη Μεγάλη Βρετανία σ. 18 7.1. H Mεγάλη Περιήγηση και η σχέση της με το φιλελληνικό κίνημα σ. 19 8.Ρώσοι φιλέλληνες κατά την επανάσταση του 1821 σ. 21 8.1. Ο Pushkin, οι Δεκεμβριστές και το Ελληνικό Ζήτημα σ. 24 9.Ο Ιταλικός φιλελληνισμός σ. 28 9.1. Ιταλοί φιλέλληνες και στελέχωση του τακτικού στρατού στην Ελλάδα. Συμμετοχή σε στρατιωτικές επιχειρήσεις. σ. 29 9.2. Συμμετοχή στην πολιτική συγκρότηση του νεοσύστατου κράτους σ. 32 9.3. Συμβολή στην έκδοση εφημερίδων σ. 33 9.4. Συμπαράσταση στην οργάνωση και διεύθυνση της ιατρικής, φαρμακευτικής και νοσοκομειακής περίθαλψης ασθενών και τραυματιών σ. 34 10.Ο πνευματικός κόσμος της Ιταλίας σ. 35 2 10.1. Λογοτέχνες και επαναστατικές ιδέες σ. 35 10.2. Πολιτικοί και επανάσταση σ. -

![ART CENTERS and PERIPHERAL ART [A LECTURE at the UNIVERSITY of HAMBURG, OCTOBER 15, 1982] Nicos Hadjinicolaou](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0140/art-centers-and-peripheral-art-a-lecture-at-the-university-of-hamburg-october-15-1982-nicos-hadjinicolaou-1190140.webp)

ART CENTERS and PERIPHERAL ART [A LECTURE at the UNIVERSITY of HAMBURG, OCTOBER 15, 1982] Nicos Hadjinicolaou

DOCUMENT Downloaded from http://direct.mit.edu/artm/article-pdf/9/2/119/1846574/artm_a_00267.pdf by guest on 24 September 2021 ART CENTERS AND PERIPHERAL ART [A LECTURE AT THE UNIVERSITY OF HAMBURG, OCTOBER 15, 1982] nicos hadjinicolaou The title of my talk is “Art Centers and Peripheral Art.” The subject to which I have assigned this title touches several aspects of our discipline. I would briefl y like to raise several questions which have led me to the discussion of this topic. 1. Naturally, the most important, most complicated question for us art historians, but I believe also for historians in general—a problem, by the way, which we shall never “solve,” but answer differently depend- ing on our points of view—is the following: how and why does form change?1 Which available tools or means make it possible for art histori- ans to capture these changes? I think that the point I am hinting at here with “art centers and peripheral art” touches on this question: in the relationship of center and periphery, in the effect of an art center, and in the dissemination of its production to the periphery. In inundating and overpowering the art production of the periphery, the history of art is also being made.2 1 This has been, no doubt, the central question at least of German-language art history since the end of the 19th century (Heinrich Wölffl in, August Schmarsow, Alois Riegl). 2 This, too, cannot be emphasized enough. The history of art is created from (among other factors) the (unequal) interrelationship of periphery and center. -

2. the American Position 1946-1949 on Greece's Claims to Southern

JOHN T. MALAKASSES THE AMERICAN POSITION 1946-1949, ON GREECE’S CLAIMS TO SOUTHERN ALBANIA The first post world war two administration that Greece was to have was installed in Athens, by a British expeditionary force which had ar rived on Greek soil at the heels of the retreating German army. Of course, it is worth emphasizing here, that the country had already been libera ted by the resistance armies, and an indigenous administration was ope rating in the land by the partisan armies of EAM, the EL AS. ' The Papandreou government, which was carried over from the Mid dle East by the British was a most subservient1 and totally depended on the later for its very existence. Not surprisingly then, that lacking mass popular support and at variance with the political institutions of the la nd, as had evolved during the occupation of the country by the Germans, it resorted to a campaign of an unpresedented, even for a Balkan state, jingoism, that was wiping to a frenzy the revanchist passions of the most politically retarted, elements of the population. Indeed, the market alie nation of the traditional political parties2, not excluding the liberal and 1. On the proverbial servility of Papandreou to the British, see a study by the OSS, British Policy toward Greece, 1941-1944, R & A No. 2818, Washington 9 Feb ruary 1945, pp. 22-26. In the annex pa. vi of the same study the following are con tained on Papandreou: «Papandreou’s habit of dealing directly with the British and of disregarding the existence of his cabinet has been exemplified on two occasions since the liberation of Greece (1) The order that the resistance groups must disband by December 10 1944 was announced after Papandreou had been in conference with General Scobie, but without the acquiesencc of his cabinet. -

ICOM Costume Newsletter 2012:2

ICOM Costume News 2012: 2 ICOM Costume News 2012: 2 17 December 2012 INTERNATIONAL COSTUME COMMITTEE COMITÉ INTERNATIONAL DU COSTUME Letter from the Chair Now we can look forward to next year’s General Dear members! Conference in Rio de Janeiro, for which we have made special efforts to create a full program of This has been an exciting year for the Costume activities and papers about a wide range of Brazilian Committee, our 50th anniversary, which was costume history and specialties. The Brazilian suitably celebrated during our meeting in Brussels organizing committee has made an exceptional in October. Corrinne ter Assatouroff and Martine effort to improve our possibilities to pursue our Vrebos prepared a whirlwind of activities in sunny costume interests at the Triennial, and Brazil is in a Brussels, including visits to museums, schools and very exciting situation regarding its costume workshops, and our colleagues offered papers on collections. Our Brazilian colleagues look forward many different aspects of lace. The theme “Lace: to welcoming us next August - I hope to see many transparency and fashion” gave us the opportunity of you there! to explore many aspects of this luxurious part of our collections, from its beginnings to its newest technological expressions. The papers will be published in a Proceedings from the meeting, Katia Johansen available next spring. December 2012 Three special events marked the Committee’s 50th anniversary: a new “old” costume for Manneken Pis was made by Committee members and presented to the city of Brussels; a thematic presentation of members’ memories of 1962 was collected and shown by Alexandra Kim; and a special, elegant chocolate cake was the crowning glory of a wonderful farewell dinner. -

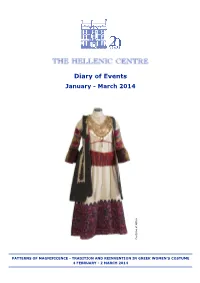

Diary of Events

Diary of Events January - March 2014 Costume of Attica of Costume PATTERNS OF MAGNIFICENCE - TRADITION AND REINVENTION IN GREEK WOMEN’S COSTUME 4 FEBRUARY - 2 MARCH 2014 JANUARY Tuesday 7 January to Thursday 30 January - Friends Room, Hellenic Centre Shadowplay A collection of paintings by Ioakim Raftopoulos, showing spontaneous gesture and experimentation with new materials, in a process to understand the specific capacity of abstraction which transcends the world of objects and representations and has an integrative and possibly anaesthetic, narcotic function. Private view on Friday 10 January, 6.30-8.30pm. For opening hours call 020 7487 5060. Supported by the Hellenic Centre. Tuesday 14 January, 7.15pm - Great Hall, Hellenic Centre Paper Icons - Orthodox Prints, A Nineteenth-Century Icon-Painters’ Collection of Greek Religious Engravings and their Role to Painters A lecture in English by Dr Claire Brisby, Courtauld Institute of Art. The lecture shows how an unknown collection of prints in a Balkan icon-painters’ archive illuminates our understanding of Greek religious engravings and painters’ use of them in their work. It discusses how their imagery explains the reasons for their production and reflects the impact of their publication in the central European centres of Vienna and Venice on their assimilation of western imagery. Particular focus is given to the fragmentary evidence of prints of two Orthodox engravings which sheds light on painters’ use of prints as sources of innovative iconography, which then leads to conclude that the role of visual prototypes should be recognised as integral part of their intended function. Free entry but please confirm attendance on 020 7563 9835 or at [email protected]. -

“The Foreigner of 1854”: a Short Novel Referring to the Cholera Epidemic of Athens in 1854

- 94 - Ιατρικά Χρονικά Βορειοδυτικής Ελλάδας - Τόμος 14ος - Τεύχος 1ο “The Foreigner of 1854”: a short novel referring to the cholera epidemic of Athens in 1854 E. Poulakou-Rebelakou 1, Summary M. Mandyla-Kousouni 2, Cholera was one of the great killers of all time. The 3 disease had spread worldwide and affected human C. Tsiamis populations in seven deadly waves. The epidemic of cholera in Athens (1854) belongs to the third cholera pandemic (1839-1856), which started from Bengal (India) in 1839, spread worldwide to Middle East, 1 Department of History of Medicine, Russia, struck the Western Europe and furthermore Medical School, National and North and Latin America. In 1854, the pandemic Kapodistrian University of Athens, moved from France to Greece and Turkey, by French Greece troops returning from the Crimean War. Cholera first affected the port of Piraeus and soon reached Athens. 2 Historical Demography, School of The novel “The Foreigner of 1854”, although a literary History, Ionian University, Corfu, text is written like a chronicle of the disease and Greece many newspapers’ refers are embodied in it. Lycoudis narrates the abandonment of the city by the citizens, the panic among the rest population, the insufficient 3 Department of Microbiology, Medical hospital beds and the efforts of the physicians to offer School, National and Kapodistrian the most of the possible adjuvant therapeutic help University of Athens, Greece to the patients. The state structures and the poor organization of those times had collapsed and the author presents a unique spectacle of an empty and destroyed small city, commenting social attitudes, humanity, religion, and criticizing all deniers of their duty. -

“Heroes” in Neo-Hellenic Art (19Th – 20Th Centuries) the New National Models and Their Development Panagiota Papanikolaou International Hellenic University

Volume 2, Issue 5, May 2015, PP 249-256 ISSN 2349-0373 (Print) & ISSN 2349-0381 (Online) www.arcjournals.org International Journal of Humanities Social Sciences and Education (IJHSSE) “Heroes” in Neo-Hellenic Art (19th – 20th Centuries) the New National Models and their Development Panagiota Papanikolaou International Hellenic University “Pity the country that needs heroes.” Bertolt Brecht Abstract The outbreak of the Greek Revolution in 1821 acted as a catalyst for the country and put in place the conditions for the occurrence of many new phenomena, such as the emergence of art, for example, which was influenced by Western mannerisms. This has been considered absolutely normal, because this is when the actual conditions for the development of art were met. The social, legal, moral and political conditions were completely overhauled and this enabled citizens to express themselves freely. (1) For Greeks, the Greek Revolution has been the great historical event out of which the new Greek state emerged. However, to achieve this, sacrifices and struggles have been necessary, which resulted in certain people standing out for their achievements, bringing back to the people’s memory the ancient myths about semi-gods and heroes as well as the saints of the Christian religion. The heroes and heroines of the new Hellenism leapt out of the Greek Revolution, lauded by poets and represented by artists. In general, there are many categories of “heroes”, as there are many definitions thereof. According to dictionaries, a “hero” is someone “who commits a valiant act, often to the point of sacrificing themselves”, a person who achieves something particularly difficult and who is admired by others. -

ITRA E-NEWSLETTER Summer 2008 Helena Kling

ITRA E-NEWSLETTER Summer 2008 Helena Kling. Editor. The consensus of the members of our association was that the Newsletter should be informal and aim at keeping us in contact with each other. I am including in this issue news and information about the upcoming conference so some items that were sent to me will be in the next issue. Our President Dr. Cleo Gougoulis and her team have put together an outstanding program. Their hard work is appreciated. The participants in the Congress will go home updated in knowledge in our field, pleased with meeting old friends, hopefully with new friends and with many memories of the good social time that is being planned. What hosts put on the table for their guests tells the story of who they are. That vegetarians will be catered for and meat eaters will be offered chicken and veal at the times of sustenance between lectures can only add to the comfort and enjoyment of the whole event. _______________________________________________ In this issue New members Photo from Brian Sutton-Smith Remembering Birgitta Publications Recommendations from Members Upcoming Conferences Burn Ken Map of Nafplion Program of the Congress How to get to Nafplion Information on Membership _____________________________________________________________________ 1 Join me in welcoming new members. The writings of our new members would fill a bookcase and to list them would fill pages so please visit their websites or google them to get to know them better. Rather than quote academic titles wrongly, they and job descriptions are easy to glitch, I am introducing everyone by name only.