A Conversation with Benjamin Barber

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

How Businesses Could Feel the Bern

HOW BUSINESSES COULD FEEL THE BERN A PRIMER ON THE DEMOCRATIC FRONT-RUNNER February 2020 www.monumentadvocacy.com/bizfeelthebern THE FRONT-RUNNER BERNIE 101 As of this week, Senator Bernie Sanders is leading national Democratic THE APPEAL: WHAT POLLING TELLS primary polls, in some cases by double-digit margins. After another early US ABOUT BERNIE’S MOVEMENT state victory in Nevada, he is the betting favorite to become the nominee. Regardless of what comes next in the primary, the grassroots fundraising prowess and early state successes Bernie has shown means he will remain a ANATOMY OF A STUMP SPEECH: formidable force until the Democratic Convention. Dismissed no more than THE CAMPAIGN PROMISES & POLICIES five years ago as a bombastic socialist from a state with fewer than 300,000 voters, Bernie is now leading a national movement that has raised more small dollar donations than any campaign in history, including $25 million in January alone. PROMISES & PAY-FORS: THE BIG- Not unlike President Trump, Bernie uses his massive and loyal following, as TICKET PROPOSALS & WHO WOULD well as his increasingly formidable digital bully pulpit, to target American PAY businesses and announce policies that could soon be the basis for a potential Democratic platform. As businesses work to adjust to the rapidly changing primary dynamics that TARGET PRACTICE: BERNIE’S TOP have catapulted Bernie to frontrunner status, we wanted to provide the basics CORPORATE TARGETS & ATTACKS - a Bernie 101 - to help guide business leaders in understanding the people, organizations and experiences that guide Bernie’s policies and politics. This basic primer also includes many of the Vermont Senator’s favorite targets, ALLIES & ADVISORS: THE ORGS, from companies to institutions to industries. -

Progressive Strategy Summit 2019 - Building Power for the Rest of Us!

20 19 BUILDING POWER FOR THE REST OF US OCTOBER 24-25 • HYATT REGENCY WASHINGTON ON CAPITOL HILL 400 New Jersey Avenue N.W. Washington, DC 20001 OUR TEAM 2 WELCOME TO OUR PROGRESSIVE COMMUNITY: Thank you for joining us for our Progressive Strategy Summit 2019 - Building Power for the Rest of Us! We are coming together because we believe that even in the midst of a constitutional crisis, there is nothing more powerful than people power. We know that real change won’t come to Washington unless and until we listen to people fighting in Shakopee, Minnesota for Amazon to accommodate workers observing Ramadan, in Kansas City, Missouri for fair, safe and affordable housing, and in Orlando, Florida for living wages. That’s why this Summit includes grassroots activists from all across our great nation, national advocates and strategists, and representatives from the over 100 member-strong Congressional Progressive Caucus. It’s unique to have a caucus co-chaired by a union member, Congressman Mark Pocan, and a grassroots organizer, Congresswoman Pramila Jayapal. We’ll hear from people fighting for change on the front lines and people fighting for change in the halls of Congress. We’ll kick off with a town hall cosponsored by She the People and the Progressive Caucus Action Fund in which women of color grassroots leaders will come together with women of color leaders in Congress to discuss the work ahead to achieve racial, gender, economic, health, LGBTQ and climate justice. We’ll give awards to outstanding progressive grassroots champions and lawmakers. And we’ll keep rolling from there into important discussions about saving our democracy, building a powerful labor movement, listening to black voters, what it takes to win, and so much more. -

June 12, 2020 Dear Vice President Biden, Every Election Is Called

June 12, 2020 Dear Vice President Biden, Every election is called "the most important in our lifetime" but, as you have emphasized, 2020 really is. Due to the twin pathogens of Trump and Trumpism, the outcome this fall could keep America on the road to lawless authoritarianism or reroute us to a stronger democracy. A crisis election as big as 1932 requires a big running mate. So why not the best? You have announced both that you will choose a woman and "the most important thing is that it has to be someone who, the day after they're picked, is prepared to be president of the United States of America if something happened." This choice of course is yours alone to make. Since you're a well-known listener, however, we'd like to offer our advice. We 100+ progressive former public officials, authors, actors, activists, advocates and scholars agree that the most important criterion is who would be most capable to be President if necessary. In our view, Elizabeth Warren has proven herself most prepared to be President if the occasion arises and deeply expert on the overlapping emergencies now plaguing America – Covid-19, Economic Insecurity, Racial Injustice and Climate Change: *She's a policy expert. During the presidential campaign, her refrain was, "I have a plan for that" – and she did. Her 50+ "plans" over the past year distinguish her as the only campaign that provided a de facto real-time transition report for whomever won the office. After her candidacy ended, she returned right back to the Senate and immediately responded to our multiple monumental crises with an array of much-lauded policy proposals. -

Citizens United Harms Democracy & Top 5 Ways We’Re Fighting to Take Democracy Back

Top 5 Ways Citizens United Harms Democracy & Top 5 Ways We’re Fighting to Take Democracy Back liz kennedy n the five years since the Supreme Court’s Citizens United decision the dominance of big money over politics and policy has grown, seemingly without restraint and with dire consequences for representative self-government. A funct ioning democracy Irequires a government responsive to people considered as political equals, where we each have a say in the public policy decisions that affect our lives. It is profoundly anti-democratic for anyone to be able to purchase political power, and when a small elite makes up a donor class that is able to shape our government and our public policy. It’s not just the amount of money being spent on campaigns and to lobby our elected representatives—which is on the rise and in- creasingly secret.1 The problem is that our current system for fund- ing elections allows a few people and special interests to have much more power over the direction of our country than the vast majority of Americans, who have different views on public policy than the wealthy elite.2 We’ve been fighting to control the improper influence of money in government, whether from wealthy individuals or cor- porate interests, since the founding of our republic.3 But we are at a low point, where large financial interests wield tremendous political power, and much of the blame rests squarely on the Supreme Court and its campaign finance decisions. Americans across the political spectrum understand that our cur- rent rules for using money in politics give the wealthy greater polit- ical power and prevent us from having an equal chance to influence 2015 • 1 the political process,4 and that government is not serving our inter- ests but rather serving special interests.5. -

About the Trainers

About the trainers: MATT BLIZEK – NATIONAL FIELD DIRECTOR, DEMOCRACY FOR AMERICA (BURLINGTON, VT) Matt is the National Field Director at Democracy for America. He was born and raised in rural Iowa and first got involved in politics at 19 while attending the University of Iowa. In 2001 he managed his first campaign in an attempt to elect a UI student to the Iowa City Council. Since then he has done Field, Fundraising and Online Organizing for numerous campaigns including the DNC, MoveOn.org, Russ Feingold, Jon Tester, and the No on 1 campaign for marriage equality in Maine. For the last four years Matt has managed national field and training programs for Democratic activists and candidates at Democracy for America. Since joining DFA he has organized over 71 campaign trainings in 33 states, training over 8,000 progressives to become better activists, campaign staff or candidates. ELLERY GOULD- COMMUNICATIONS (NASHVILLE, TN) A campaign veteran before he finished college, Ellery has experience at virtually every level of politics and in every region of the country; from City Hall to the halls of Congress, Connecticut to Arizona. A Tennessee native, he took his talents for winning "red states" to the Democratic Congressional Campaign Committee in 2006 where he oversaw media campaigns for some of the toughest races in the nation and helped bring a Democratic majority to Congress for the first time since 1994. Most recently, Ellery managed the U.S. Senate campaign of a little-known former state legislator in Georgia – a state that hasn’t seen a top-of-the-ticket Democratic win in over a decade – turning it into one of the most improbable and competitive races of 2008. -

Complete Report

NEWSRelease 1615 L Street, N.W., Suite 700 Washington, D.C. 20036 Tel (202) 419-4350 Fax (202) 419-4399 EMBARGOED FOR RELEASE: WEDNESDAY, APRIL 6, 2005, 4:00 P.M. An In-Depth Look THE DEAN ACTIVISTS: THEIR PROFILE AND PROSPECTS FOR FURTHER INFORMATION CONTACT: Andrew Kohut, Director PROJECT ADVISORS: Jodie Allen, Senior Editor Maxine Isaacs, Harvard University Scott Keeter, Director of Survey Research Karlyn Bowman, American Enterprise Institute Carroll Doherty, Associate Director Michael Dimock, Associate Director Carolyn Funk, Senior Project Director Nilanthi Samaranayake, Peyton Craighill and Nicole Speulda, Project Directors Jason Owens, Research Assistant Kate DeLuca, Courtney Kennedy, Staff Assistants Pew Research Center for The People & The Press 202/419-4350 http://www.people-press.org An In-Depth Look THE DEAN ACTIVISTS: THEIR PROFILE AND PROSPECTS lthough former Vermont governor Howard Dean Activists: Highly Educated Dean failed to win the Democratic and Engaged, But Not So Young presidential nomination, his campaign left a Dean All A * strong imprint on the political world. It assembled a activists Dems Age % % network of over a half-million active supporters and Under 30 18 18 contributors, raised over $20 million in mostly small 30-44 26 28 45-64 42 33 donations online, and demonstrated the power of the 65+ 14 20 internet as a networking and mobilizing tool in politics. Education Less than B.A. 21 74 Who are the internet activists – the people B.A. degree 25 14 Grad school 54 11 widely known as “Deaniacs” – who joined the Dean College grad/age 45-64 34 9 campaign as it slowly grew from asterisk status in early Dean 2003 polls to the frontrunner position at the beginning activists of 2004? A new Pew survey provides the first detailed During the primaries % Gave money to any candidate 85 look at the cyber-soldiers of this pioneering campaign. -

Deaniacs and Democrats: Howard Dean’S Campaign Activists

Deaniacs and Democrats: Howard Dean’s Campaign Activists Scott Keeter Cary Funk Courtney Kennedy Pew Research Center Pew Research Center and Pew Research Center and [email protected] Virginia Commonwealth University Joint Program in Survey Methodology [email protected] [email protected] The Pew Research Center for the People & the Press 1615 L St. NW, Suite 700 Washington, DC 20036 202-419-4350 Presented at the State of the Parties conference, University of Akron, Akron, Ohio, October 5-7, 2005. Abstract In his quest for the 2004 Democratic presidential nomination, Howard Dean energized hundreds of thousands of supporters nationwide, many of whom were engaging in the political process for the first time. In addition to its ideological appeal, the Dean campaign was considered to be revolutionary in its use of the internet for facilitating donations and coordinating volunteers. This paper presents findings from a unique panel survey of Dean campaign supporters conducted by the Pew Research Center in September and November of 2004. The study examines who the campaign supporters were, their political orientations, where they fit in the Democratic Party and where would take the party in the future. About four in ten (42%) Dean supporters were participating in their first political campaign – yet contrary to some media accounts most activists were not young but rather drawn from the Baby Boomer generation. The political orientation of campaign supporters was decidedly more liberal than Democrats as a whole or than the general population. The war in Iraq was a top issue for this group; 99% of campaign supporters opposed the war. -

Meet the Trainers

Meet the trainers: MATT BLIZEK – NATIONAL FIELD DIRECTOR , DEMOCRACY FOR AMERICA (B URLINGTON , VT) Matt is the National Field Director at Democracy for America. He was born and raised in rural Iowa and first got involved in politics at 19 while attending the University of Iowa. In 2001 he managed his first campaign in an attempt to elect a UI student to the Iowa City Council. Since then he has has done Field, Fundraising and Online Organizing for numerous campaigns including the DNC, MoveOn.org, Russ Feingold, Jon Tester, and the No On 1 campaign for marriage equality in Maine. For the last four years Matt has managed national field and training programs for Democratic activists and candidates at Democracy for America. Since joining DFA he has organized over 71 campaign trainings in 33 states, training over 8,000 progressives to become better activists, campaign staff or candidates. ANASTASIA APA – FINANCE (MIAMI , FL) Anastasia Apa is a political management and fundraising consultant who has traveled the country for the past eight years to help Democrats build the strongest campaigns possible. She has worked at the local, state and federal level in the Southern, Midwestern and Eastern part of the country. Apa focuses on fundraising and planning because she believes a solid plan and the money to implement it is the way to a win. She is based in Miami and runs a campaign staffing network which trains, retains and places experienced campaign operatives on races. JOHN ROWLEY – COMMUNICATIONS (NASHVILLE , TN) John Rowley’s first work was in radio and television in Burlington, Iowa. -

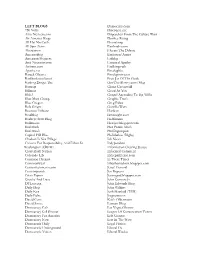

LEFT BLOGS 750 Volts Afro-Netizen.Com Air America Blogs

LEFT BLOGS Democrats.com 750 Volts Discourse.net Afro-Netizen.com Dispatches From The Culture Wars Air America Blogs Donkey Rising All Hat No Cattle Dvorakorg All Spin Zone Earthside.com Altercation Elevate The Debate Americablog Eschaton/Atrios American Progress Fafblog Anti-Neocons.com Fanatical Apathy Antiwar.com Faulkingtruth Apathy.net Firedoglake Barack Obama Firedupmissouri Barkbarkwoofwoof Fruit Jar Of The Gods Barking Dingo, The Get-The-Skinny.com/Blog Bartcop Glenn Greenwald Billmon Good As You Blah3 Gospel According To Big Willie Blue Mass Group Graphic Truth Blue Oregon Greg Palast Bob Geiger Guerilla Wars Booman Tribune Harikari Bradblog Hinessight.com Buckeye State Blog Hoffmania Bullmoose Hossjoe.blogspot.com Bushflash Hot Potato Mash Bushwatch Huffingtonpost Capitol Hill Blue Hullabaloo (Digby) Chicken Is Not Pillage Ich News Citizens For Responsibility And Ethics In Indypendent Washington (CREW) Information Clearing House Clusterfuck Nation Informed Comment Colorado Lib Inthepinktexas.com Common Dreams In These Times Commonweal Isbushantichrist.blogspot.com Consortiumnews.com Jesus' General Counterpunch Joe Bageant Crisis Papers Joemygod.blogspot.com Crooks And Liars John Conyers Jr. DFLers.org John Edwards Blog Daily Blog John Wilkins Daily Kos Josh Marshall (TPM) Daily Pulse Jregrassroots David Corn Keith Olbermann David Sirota Lamont Blog Democracy Cafe Las Vegas Gleaner Democracy Cell Project League Of Conservation Voters Democracy For America Left Coaster Democracy Now Left In The West Democratic Daily Legal Fiction -

The Whole World Is Networking: Crafting Networked Politics from Howard Dean to Barack Obama

The Whole World is Networking: Crafting Networked Politics from Howard Dean to Barack Obama Daniel Kreiss Ph.D. Candidate Department of Communication Stanford University Paper presented at the session “Artifacts, Institutions, and Practices in the Production of Contemporary U.S. Politics.” Society for Social Studies of Science Annual Meeting, Washington, D.C. October 29, 2009. Kreiss, The Whole World is Networking In the classic The Whole World is Watching Todd Gitlin argued that by the early 1970s the Students for a Democratic Society (SDS), and with it much of the New Left, had come apart at the seams under the gaze of the mass media.i The professional press had extraordinary power to frame the movement on its own terms, focusing on highly symbolic forms of protest such as draft-card burning. In the process, the media not only shaped perceptions of the movement for the outside world, they came to define it and the grounds upon which it acted for its leadership and members alike. For Gitlin, this meant that there was no longer any representational space from which to critique the dominant power structure. Social movements were forcibly subsumed within a vast cultural industry and yet needed it to pursue their social objectives: “Just as people as workers have no voice in what they make, how they make it, or how the product is distributed and used, so do people as producers of meaning have no voice in what the media make of what they say or do, or in the context within which the media frame their activity”.ii The picture that Gitlin paints is unrecognizable to the activist who came of age in the digital era. -

May 15, 2019 the Honorable Bernie Sanders Bernie 2020 PO Box 391

May 15, 2019 The Honorable Bernie Sanders Bernie 2020 PO Box 391 Burlington, VT 05402 Dear Senator Sanders, Congratulations on your decision to run for president. Americans deserve a robust debate about our country’s future and who has a voice in shaping it. We write to you as members of the Declaration for American Democracy coalition as well as voting rights, good government, civil rights, faith, environmental, labor, and grassroots organizations representing millions of Americans committed to protecting and expanding the right to vote, ending the dominance of big money in politics, and restoring ethics and accountability to Washington. We applaud your sponsorship of the For the People Act, and your choice to reject corporate PAC and fossil fuel industry money for your campaign. Your personal decision to lead by example on these issues is an important first step in rebuilding the public’s faith in our political system. Now we look forward to seeing your comprehensive plan to address the structural inequities that have denied too many people access to the ballot and silenced too many voices, while giving those with wealth and access undue influence in Washington. Our democratic institutions are under attack, and need renewal and repair. We strongly encourage you to incorporate into your campaign platform the principles of the attached democracy reform agenda developed by the Declaration for American Democracy coalition. This agenda is reflected in the historic passage in the For the People Act, introduced as H.R. 1—the first bill of the new House Democratic majority—to signify its priority. It passed the House in March with the support of all Democratic House members. -

The Democratic Strategist List of Progressive Organizations That Support: A

A Journal of Public Opinion & Political Strategy www.thedemocraticstrategist.org GETTING READY FOR 2018 AND 2020: The Democratic Strategist List of Progressive Organizations That Support: a. Democratic Candidate Recruitment and Training, b. Democratic Political Campaign Operation and Management c. Pro-Democratic Grass Roots Voter Organizing By James Vega and J. P. Green One of the most powerfully encouraging events since Donald Trump’s election has been the dramatic emergence of a new generation of energetic progressive candidates and new political organizations that seek to seriously challenge Republican incumbents at every level of American politics. The reason this is so vitally important is that anemic progressive and Democratic political participation in non-presidential years and at every level below the race for the oval office has been the Republican Party’s greatest single political asset, allowing it to maintain its dominance in both houses of Congress and in state legislatures and governorships across the country even as Democratic presidential candidates won the popular vote in four of the last five presidential elections. In far too many districts across America the Democratic Party has not supported serious challenges to Republican candidates for some time or maintained robust local offices and staff to carry out continuing efforts at voter contact, persuasion and mobilization. To successfully challenge incumbent Republican officeholders, new Democratic candidates will need a restored progressive political base and infrastructure. GOP candidates now have a deep local network of conservative grass roots organizations to rely upon – the NRA, right to life groups, Tea Party organizations and so on. Democrats will need comparably powerful neighborhood and community level political organizations to even the playing field.