Environmental Flows for the River Murray Report on The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

River Murray – Darling to Sea Expert Technical Workshop, 1-3 July

River Murray – Darling to Sea Expert Technical Workshop, 1-3 July Part B - Workshop Outcomes 2: Threats 57 River Murray – Darling to Sea Expert Technical Workshop, 1-3 July Part B - Workshop Outcomes 2: Threats Threats and Future Trends Climate Change A recent Pew Centre report on Aquatic Ecosystems and Global Climate Change1 reported: Increases in water temperatures as a result of climate change will alter fundamental ecological processes and the geographic distribution of aquatic species. Such impacts may be ameliorated if species attempt to adapt by migrating to suitable habitat. However, human alteration of potential migratory corridors may limit the ability of species to relocate, increasing the likelihood of species extinction and loss of biodiversity. Changes in seasonal patterns of precipitation and runoff will alter hydrologic characteristics of aquatic systems, affecting species composition and ecosystem productivity. Populations of aquatic organisms are sensitive to changes in the frequency, duration, and timing of extreme precipitation events, such as floods or droughts. Aquatic ecosystems have a limited ability to adapt to climate change. Reducing the likelihood of significant impacts to these systems will be critically dependent on human activities that reduce other sources of ecosystem stress and enhance adaptive capacity. The impacts of anthropogenic induced climate change lead to increased temperature and reduced rainfall. Reduced rainfall and changed seasonality of rainfall can have a significant effect runoff (in general, a 1% decline in rainfall equates to a 2-3% decline in runoff). In addition, changes to local rainfall patterns can have an important influence on associated wetlands (averaged annual rainfall and modelled runoff are shown by figure below). -

The Coorong Lower Lakes and Murray Mouth Directions for a Healthy Future

The Community Consultation Report: Murray Futures: Lower Lakes & Coorong Recovery Community Consultation Report The Coorong, Lower Lakes and Murray Mouth: Directions for a Healthy Future APPENDICES June 2009 Page 1 The Community Consultation Report: Murray Futures: Lower Lakes & Coorong Recovery Appendices Appendix 1 Promotion - Distribution Points 3 Appendix 2 Promotion - Media Coverage 6 Appendix 3 Promotion - Advertisements & Web Copy 7 Appendix 4 Community Information Sessions – Notes 22 Appendix 5 Community Information Sessions - PowerPoint Presentation 44 Appendix 6 Community Information Sessions - Feedback Survey 49 Appendix 7 Targeted Meetings - Notes 53 Appendix 8 Targeted Meetings - (Example) PowerPoint Presentation 64 Appendix 9 Written Submissions - List 67 Appendix 10 Written Submissions - Summaries 69 Appendix 11On-line Survey Report (from Ehrenberg-Bass) 107 Page 2 The Community Consultation Report: Murray Futures: Lower Lakes & Coorong Recovery Appendix 1 Promotion - Distribution Points Councils: Alexandrina Council Coorong District Council Strathalbyn Council Office Coorong District Council (Tailem Bend and Tintinara) Mt Barker District Council Rural City of Murray Bridge Libraries: Coomandook Community Library DEWHA Library Goolwa Public Library Meningie Community Library Mount Barker Community Library Mt Compass Library Murray Bridge Library National Library of Australia ACT Library Port Elliot Library SA Parliamentary Library State Library Adelaide Strathalbyn Community Library Tailem Bend Community Library Tintinara -

REPORT for the WEEK ENDING Wednesday, 3 October 2007

REPORT FOR THE WEEK ENDING Wednesday, 3 October 2007 Our Ref : M2006/01015/PRS, AS 5 October, 2007 Trim Ref : 07/12486 Rainfall and Inflows The dry weather has continued across the Murray-Darling Basin with most regions receiving less than 10mm of rain during the past week (see Map 1). The Victorian alpine region received the highest falls (up to 50 mm), and this resulted in a slight increase in flows in the Ovens, Kiewa and Mitta Mitta Rivers. During the month of September, rainfall averaged across the Murray-Darling Basin was the driest in the historical record back to 1900 (see Map 2) and river flows continued to recede. The total monthly inflow was 210 GL which is only 13 % of the long term average for September. This makes it the 5th driest September on record. Inflows have now been below average for the last 24 consecutive months. River operations Dartmouth Reservoir (currently at 680 GL or 17 % capacity) and Hume Reservoir (870 GL or 29 % capacity) continue to slowly rise, while Lake Victoria (530 GL and 78 % capacity) is slowly falling. The total system storage (including Menindee Lakes) is currently at 2130 GL which is well below the long term average for this time of year (7100 GL) and also below the storage volume 12 months ago (3350 GL). The low storage volumes, combined with low inflows, have resulted in very limited water availability along the River Murray. The October Drought Update (attached) provides the latest information on outlooks and responses to the drought. Flows along the entire length of the River Murray are being kept to a minimum and some weir pools are partially drawn down to save water. -

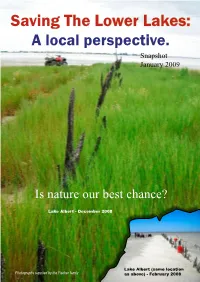

Saving the Lower Lakes: a Local Perspective

Saving The Lower Lakes: A local perspective. Snapshot January 2009 Is nature our best chance? Lake Albert - December 2008 Lake Albert (same location Photographs supplied by the Fischer family as above) - February 2008 Diagram 1: Normal conditions In a nutshell: The Problem Lake Albert & Lake Alexandrina Facing the Lower Lakes Sand/silt lake bed Acid sulfate soils The amount of water reaching the Lower Lakes is declining. Diagram 2: Drought conditions As the water levels in Lake Alexandrina and Lake Acid sulfate soils emerge when Albert recede, soils in the lake beds are turning acidic lake bed exposed to oxygen when exposed to air. As the lakes continue to dry out, the water is becoming Sand/silt lake bed Acid sulfate soils increasingly saline and more acidic hot spots are emerging on exposed lake beds. Diagram 3: How to manage acid soils How to address the dangers associated with this 1. Revegetation natural phenomenon is the subject of much debate and 2. Apply lime & mulch anxiety. The South Australian Government is proposing 3. Slowly re-cover with water - using wind tides to open sections of the 7.6km of barrages that block the when flows return Lower Lakes from the Southern Ocean and flood the Lakes with sea water to keep the soils submerged. Sand/silt lake bed The Government is also proposing to construct a series Acid sulfate soils of weirs to cordon off areas within the lakes. The large majority of Lower Lakes residents do not want sea water used and claim the use of weirs The lakes currently receive a minimum of 350 would hinder the recovery from the current drought. -

Submission: Inquiry Into Climate Change and the Australian

SENATE ENQUIRY: RESEARCH INFORMATION & CONCLUSIONS 1. Murray Darling Basin Commission (MDBC) Media Releases I have been analysing the Commission’s Weekly Reports since June 2007 and I’ve come to the following conclusions re the lack of environmental vision and priorities of the MDB Commission. MDB Inflows/Storage Levels When the MDBC says that “MDB inflows for June 2008 were 95 GL” most people hearing this figure wouldn’t know that this inflow figure was generated from only a small part of the huge Murray Darling Basin catchment. For example, any diagram in the MDBC Weekly Reports showing ‘Murray System Inflows’ always states that the figures do not include Snowy Scheme or Darling River inflows. Yes whilst it is true that inflows for the specific part of the MDB catchment that the MDBC has control over were a record low for this June, the actual figure for the whole of the Murray Darling Basin would’ve been considerably higher. Furthermore, the Snowy inflows should also be added into any report on monthly inflows as they are actually part of the Murray and Murrumbidgee’s flows. My take on this selective reporting of inflows is that it conveniently allows the MDBC to justify not allowing emergency environmental flows for the Lower Lakes & Coorong because “MDB inflows were only 95 GL in June”. My view is that the term ‘MDB Inflows’ should be called ‘MDB Commission Inflows’ and should not be confused with what would be the much larger figure of ‘Total MDB Inflows’. Furthermore, there should be a public education campaign to explain the difference between the two – specifically the actual percentage of the total MDB catchment the ‘MDB inflows’ applies to, plus a comparison between the median annual inflows for the Total MDB and the median annual inflows of the much smaller MDB Commission section of the catchment. -

A Weir on the Murray at Wellington, SA

NSWIC PO Box R1437 Royal Exchange NSW 1225 NEW SOUTH Tel: 02 9251 8466 WALES Fax: 02 9251 8477 IRRIGATORS’ [email protected] www.nswic.org.au COUNCIL ABN: 49 087 281 746 A Weir on the Murray at Wellington, SA What is a Weir Generally constructed from concrete, metal, wood or rocks, weirs are built across a stream or river for the purpose of raising the water level behind it or diverting its flow. Example: Weir at Coburg Lake in Victoria. What is The Wellington Weir The proposed Wellington Weir will be a temporary structure at Pomanda Island near Wellington, South Australia (SA) that will separate the River Murray from Lake Alexandrina (part of the Lower Lakes). The weir is expected to cost $100m, take nine months to construct and has received Cabinet approved expenditure of up to $14.4 m for the preliminary works. A weir creates a physical barrier, in this case between the Murray River and the Lower Lakes. By doing so it creates a weir pool that would raise the water level around the SA Water pumps, thereby securing the water supply for Adelaide. Another function of the weir is preventing saline and potentially acidic water from flowing back upstream towards the source of the state's drinking water. Building a temporary weir is not the preferred option for the SA Government but there may be no other option available to secure their water supply. The weir would remain in place until water storage levels and flows in the Murray-Darling Basin (MDB) improved to a level where it was considered the system had recovered from these extremely rare low flow conditions. -

History, Politics and Conflict in the Southern Murray-Darling Basin: an Ethnography

History, Politics and Conflict in the Southern Murray-Darling Basin: An ethnography Gil Hardwick BA.Hons BLitt.Hons M.Crim.Just (W.Aust) SFSPE Senior Research Anthropologist Independent Social and Environmental Audit Perth, July 2019 History, Politics and Conflict in the Southern Murray-Darling Basin: An ethnography Gil Hardwick BA.Hons BLitt.Hons M.Crim.Just (W.Aust) SFSPE Senior Research Anthropologist Independent Social and Environmental Audit Perth, Western Australia July 2019 History, Politics and Conflict in the Southern Murray-Darling Basin: An ethnography. Author: Hardwick, Gil. Published by eBooks West West Perth, 2005, Western Australia Cover image, Wikipedia Commons Cover Design by Gil Hardwick Typeset by the author. Copyright © Gil Hardwick 2019 ISBN: 978-0-9923704-9-7 (ebook) The right of Gilbert John Hardwick to be identified as author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the provisions of the Australian Copyright Act 1968. CONTENTS Author Biography and Declaration of Interest i Introduction iii Locating the Central Murray Geography 1 History 5 Philosophy 10 Politics 11 Human Dynamics Confrontation 17 Consequences 23 Transhumance 28 The Drought Myth Innovation 32 Division 37 Federation 40 Panic 46 Prospects for Participatory Reform Dispute 51 Remediation 54 Community 60 Conclusion 63 Author Biography and Declaration of Interest The author of this study was born in Griffith, NSW, and grew up from the age of four in Deniliquin. He is directly descended along many lines from early pioneering families dating from the 1840s along the Murray, Murrumbidgee and Lachlan Rivers; from Port Phillip in Victoria, Kapunda and Mount Gambier in South Australia, Morago and Pretty Pine on the Deniliquin Run, to Merriwagga, Hillston, Temora and beyond. -

River Murray – Darling to Sea

River Murray – Darling to Sea Ecological Community: Expert Technical Workshop Report Threatened Species Scientific Committee 1 - 3 July, 2009 Adelaide Image Credits: Lake Albert (G.Newton) Pelicans (G. Newton) River Murray Gorge (K. Walker) Wetlands (SA MDB NRM Board) Murray Mouth (K. Walker) River Murray–Darling to Sea Expert Technical Workshop, 1-3 July 2009 Threatened Species Scientific Committee The establishment of the Threatened Species Scientific Committee is provided for under the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (EPBC Act). The EPBC Act also sets out the functions of the Committee. These include advising the Commonwealth Environment Minister on the amendment and updating of lists for threatened species, threatened ecological communities, and key threatening processes together with the making or adoption of recovery plans and threat abatement plans. How to cite this report Threatened Species Scientific Committee (2010) River Murray – Darling to Sea Ecological Community: Expert Technical Workshop Report, 1-3 July 2009, Adelaide. Report to Department of the Environment, Water, Heritage and the Arts, Canberra. Disclaimer This report was compiled by the Threatened Species Scientific Committee. Release of this report does not imply endorsement of all of its contents by the Commonwealth, the Threatened Species Scientific Committee, workshop participants, or other experts. 1 River Murray – Darling to Sea Ecological Community: Expert Technical Workshop Report Threatened Species Scientific Committee 1-3 July 2009, Adelaide River Murray–Darling to Sea Expert Technical Workshop, 1-3 July 2009 Table of Contents PART A: Executive Summary, Introductory Material and Methods Executive Summary 3 Ecological Community Description (including Table 1 - page 4) 3 Threats (including Table 2 - page 8) 6 Listing Criteria 9 Introductory Material 11 EPBC Act and Listing Process 11 Approach of the Threatened Species Scientific Committee 13 Listing Criteria under the EPBC Act (incl. -

Intergovernmental Agreement on Addressing

INTERGOVERNMENTAL AGREEMENT ON ADDRESSING WATER OVERALLOCATION AND ACHIEVING ENVIRONMENTAL OBJECTIVES IN THE MURRAY-DARLING BASIN Between the Commonwealth of Australia and the Governments of New South Wales, Victoria, South Australia, and the Australian Capital Territory PREAMBLE 1. The Parties agree to implement this Agreement in recognition of the need to address overallocation of water resources and achieve environmental objectives in the Murray- Darling Basin (MDB). 2. In August 2003, the Parties to this Agreement agreed to provide new funding of $500 million over five years to address water overallocation in the MDB, comprising the following contributions; Commonwealth Government $200 million, New South Wales $115 million, Victoria $115 million, South Australia $65 million and the Australian Capital Territory $5 million. 3. This Agreement establishes arrangements for the recovery and management of water to support the decision by the MDB Ministerial Council of 14 November 2003 to implement a first step to address the declining health of the River Murray system (the Living Murray First Step decision), and to address other water overallocation issues in the MDB. 4. The Murray-Darling Basin Agreement (1992) and the relevant legislation enacted by each of the Parties to support the Murray-Darling Basin Agreement (1992) and joined by the Australian Capital Territory through a Memorandum of Understanding dated 27 March 1998 provide the statutory framework within which the Parties will work to achieve the specific objectives of this Agreement. 5. The Parties agree to implement this Agreement consistent with the National Water Initiative Intergovernmental Agreement and its objective of a nationally compatible system of managing surface and groundwater resources for rural and urban use that optimises economic, social and environmental outcomes. -

480 Date Received

Submission of the River, Lakes and Coorong Action Group Inc. Re: Inquiry into the socio‐economic impact of the proposed Murray Darling Basin Authority’s Guide to the Proposed Basin Plan on regional Communities1 Table of Contents 1. Covering letter 2. Executive Summary 2 3. River, Lakes and Coorong Action Group Inc. (RLCAG) 3 3.1 Who are we? 3.2 Our work 4. The ‘Great Southern Lakes’ (GSL): Icon and indicator 5 5. RLCAG ‘Engagement’ with the MDBA Plan 6 6. Modelling Engagement and Identifying Key Issues 6 6.1 The Fresh Water Embassy 6.2 The Water Election Team 6.2.1 ‐ 20 March 2010 6.2.2 ‐ 21 August 2010 6.3 The People’s Forum on Water, 18 October 2010 6.3.1 Forum format 6.3.2 Forum deliberations 6.3.3 Big picture issues 7. Have we been consulted? 12 8. The Murray‐Darling Basin Authority and the Proposed Plan: A SWOT analysis? 13 (Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities, Threats) 9. Persistent Questions, Omissions and Silences 15 10. Background Readings 16 1 NB. This submission is an annotated version of our submission (Dec 2010) to the MDBA. Specific comments for the Inquiry are highlighted in purple. These draw on the broader points that were made for the MDBA. 1 2. Executive Summary The River, Lakes and Coorong Action Group Inc (RLCAG) is an independent community‐based, action‐ oriented organisation with expertise in river ecology and a track record of engaging with MDB matters via submissions, symposia, meetings and campaigns. The health of the ‘Great Southern Lakes’ (Lakes Alexandrina and Albert), the Coorong and Murray Mouth is central to achieving the objects of the Water Act 2007 and in a number of submissions re EPBC matters RLCAG has argued that maintaining connectivity in the ‘Great Southern Lakes’ (GSL) is central to achieving a healthy, resilient river system. -

Annual Report 2006 - 2007

The Coorong District Council Annual Report 2006 - 2007 Creating a Better Future ~ with Pride The Coorong District Council 2006/07 Annual Report Our Vision is: Creating a Better Future ~ with Pride Our Mission is: ¾ To provide strong leadership. ¾ To listen and be sensitive to the community. ¾ To serve the community with equality. ¾ To actively encourage and support enterprise for local prosperity. ¾ To foster community health. ¾ To protect and enhance the environment. Our Core Values are: The Coorong District Council has a commitment to balancing the following core values: ¾ Integrity ¾ Reliability ¾ Consistency ¾ Continuous improvement ¾ Financial responsibility ¾ Quality customer service ¾ Acting in the best interest of the community The Coorong, view from Long Point. The Coorong District Council 2006/07 Annual Report CONTENTS Mayor’s Message ..................................................................................... 1 Chief Executive Officer’s Report............................................................. 3 Council Overview .................................................................................... 5 Governance .............................................................................................. 6 Organisational Structure......................................................................... 10 Departmental Reports • Corporate Services ..................................................................... 11 • Development & Environmental Services................................... 19 • Technical Services..................................................................... -

Coorong and Lakes Alexandrina and Albert Ramsar Wetland

Coorong and Lakes Alexandrina and Albert Ramsar Wetland The Coorong and Lakes Alexandrina and Albert wetland is one of Australia’s most important wetland areas. Australia designated the site, covering approximately 140,500 ha in South Australia, as a Wetland of International Importance under the Ramsar Convention on Wetlands in 1985. Parts of the Coorong also form the Coorong National Park and Game Reserve. Values of the wetland site The Coorong is a long, shallow saline lagoon that stretches more than 100 km and that is separated from the Southern Ocean by a narrow sand dune peninsula. It marks the termination of Australia’s longest river, the Murray. The Lakes Alexandrina and Albert are comprised of fresh to brackish/saline waters. With its diversity of ecological features, the site provides a wide range of habitats. Waders and waterfowl are the predominant species, including the Curlew Sandpiper, Pelicans at Coorong National Park (B Gray & DEWHA) Banded Stilt, Red-capped Plover, Masked Lapwing, Red- kneed Dotterel, Black Swan, Cape Barren Goose, Musk Changes to ecological condition Duck, Straw-necked Ibis, Royal Spoonbill, Rufus Night Heron and Australian Pelican. The ecological characteristics of the area have been altered significantly since extensive water extraction from The site has a unique mosaic of 23 wetland types and the Murray-Darling Basin commenced in the 1800s and provides habitat for nationally threatened species such as barrages were constructed to separate the lakes from the the Orange Bellied Parrot, Southern Mount Lofty Ranges estuary in the 1930s. Extracting high volumes of water Emu Wren and the Murray Cod.