Bruce Springsteen's Perspective of the American Dream Heads Into

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Greetings 1 Greetings from Freehold: How Bruce Springsteen's

Greetings 1 Greetings from Freehold: How Bruce Springsteen’s Hometown Shaped His Life and Work David Wilson Chairman, Communication Council Monmouth University Glory Days: A Bruce Springsteen Symposium Presented Sept. 26, 2009 Greetings 2 ABSTRACT Bruce Springsteen came back to Freehold, New Jersey, the town where he was raised, to attend the Monmouth County Fair in July 1982. He played with Sonny Kenn and the Wild Ideas, a band whose leader was already a Jersey Shore-area legend. About a year later, he recorded the song "County Fair" with the E Street Band. As this anecdote shows, Freehold never really left Bruce even after he made a name for himself in Asbury Park and went on to worldwide stardom. His experiences there were reflected not only in "County Fair" but also in "My Hometown," the unreleased "In Freehold" and several other songs. He visited a number of times in the decades after his family left for California. Freehold’s relative isolation enabled Bruce to develop his own musical style, derived largely from what he heard on the radio and on records. More generally, the town’s location, history, demographics and economy shaped his life and work. “County Fair,” the first of three sections of this paper, will recount the July 1982 episode and its aftermath. “Growin’ Up,” the second, will review Bruce’s years in Freehold and examine the ways in which the town influenced him. “Goin’ Home,” the third, will highlight instances when he returned in person, in spirit and in song. Greetings 3 COUNTY FAIR Bruce Springsteen couldn’t be sitting there. -

Hungry Heart

NONE BUT THE HUNGRY HEART Fellowship Bible Church From the leadership development ministry of FELLOWSHIP BIBLE CHURCH MISSIONS The contents in this devotional are a selection of writings from many Christian authors compiled by Miles Stanford. the true character of the old material--i.e. FORWARD all that he is as a child of Adam and a man in the flesh--and to be as dissatisfied with it None But the Hungry Heart is a as God is. You may see this in Job and devotional series that will help you in your Saul of Tarsus. One of them said, "I abhor Christian growth and walk with the Lord. myself," and the other said, "I know that in The first issue in this series was published me (that is, in my flesh) dwelleth no good in 1968 and the final issue was completed thing." Such language as this is the mark of in 1987. For a period of approximately 20 one born again. He identifies himself with years, Miles Stanford has collected and that new "inward man" which is of God, categorized quotes from some of the best and he judges everything of a contrary authors in the realm of Christian growth. nature to be sin. In itself this is not a happy Contained at this site, you will find the experience. It is not very pleasant for one intimate truths of God's Word explained who has been self-sustained and self- and expounded by His humble servants. satisfied in a moral and religious life to find that there is not one bit of good in him. -

Songs by Artist

Reil Entertainment Songs by Artist Karaoke by Artist Title Title &, Caitlin Will 12 Gauge Address In The Stars Dunkie Butt 10 Cc 12 Stones Donna We Are One Dreadlock Holiday 19 Somethin' Im Mandy Fly Me Mark Wills I'm Not In Love 1910 Fruitgum Co Rubber Bullets 1, 2, 3 Redlight Things We Do For Love Simon Says Wall Street Shuffle 1910 Fruitgum Co. 10 Years 1,2,3 Redlight Through The Iris Simon Says Wasteland 1975 10, 000 Maniacs Chocolate These Are The Days City 10,000 Maniacs Love Me Because Of The Night Sex... Because The Night Sex.... More Than This Sound These Are The Days The Sound Trouble Me UGH! 10,000 Maniacs Wvocal 1975, The Because The Night Chocolate 100 Proof Aged In Soul Sex Somebody's Been Sleeping The City 10Cc 1Barenaked Ladies Dreadlock Holiday Be My Yoko Ono I'm Not In Love Brian Wilson (2000 Version) We Do For Love Call And Answer 11) Enid OS Get In Line (Duet Version) 112 Get In Line (Solo Version) Come See Me It's All Been Done Cupid Jane Dance With Me Never Is Enough It's Over Now Old Apartment, The Only You One Week Peaches & Cream Shoe Box Peaches And Cream Straw Hat U Already Know What A Good Boy Song List Generator® Printed 11/21/2017 Page 1 of 486 Licensed to Greg Reil Reil Entertainment Songs by Artist Karaoke by Artist Title Title 1Barenaked Ladies 20 Fingers When I Fall Short Dick Man 1Beatles, The 2AM Club Come Together Not Your Boyfriend Day Tripper 2Pac Good Day Sunshine California Love (Original Version) Help! 3 Degrees I Saw Her Standing There When Will I See You Again Love Me Do Woman In Love Nowhere Man 3 Dog Night P.S. -

Bruce Springsteen Roses and Broken Hearts Mp3, Flac, Wma

Bruce Springsteen Roses And Broken Hearts mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Rock Album: Roses And Broken Hearts Country: Italy Released: 1992 MP3 version RAR size: 1212 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1156 mb WMA version RAR size: 1553 mb Rating: 4.3 Votes: 606 Other Formats: ADX AHX FLAC TTA MIDI AUD MPC Tracklist 1-1 Tunnel Of Love 1-2 Be True 1-3 Adam Raised A Cain 1-4 Two Faces 1-5 All That Heaven Will Allow 1-6 Seeds 1-7 Roulette 1-8 Cover Me 1-9 Brilliant Disguise 1-10 Spare Parts 1-11 War 1-12 Born In The Usa 2-1 Tougher Than The Rest 2-2 Ain't Got You 2-3 She's The One 2-4 You Can Look 2-5 I'm A Coward 2-6 I'm On Fire 2-7 One Step Up 2-8 Part Man, Part Monkey 2-9 Backstreets 2-10 Dancing In The Dark 2-11 Light Of Day 3-1 Born To Run 3-2 Hungry Heart 3-3 Glory Days 3-4 Rosalita 3-5 Have Love Will Travel 3-6 Tenth Avenue Freeze Out 3-7 Sweet Soul Music 3-8 Raise Your Hand 3-9 Little Latin Lupe Lu 3-10 Twist And Shout Notes Recorded at the Shoreline Amphitheatre in Mountain View, CA on May 3, 1988 Barcode and Other Identifiers Barcode: 8013013922124 Other versions Category Artist Title (Format) Label Category Country Year Roses And Broken Bruce Gamble BSGR-16/17/18 Hearts (3xCD, BSGR-16/17/18 Europe 1988 Springsteen Records Unofficial) Related Music albums to Roses And Broken Hearts by Bruce Springsteen Bruce Springsteen & The E Street Band - LA Sports Arena, California 1988 Bruce Springsteen - Ultimate Collection Bruce Springsteen & The E Street Band - Stockholm 4th May 2013 Bruce Springsteen - Born To Rock Live at the tower of Philadelphia December 31 1975 Bruce Springsteen - Suave Young Man Bruce Springsteen - The Complete Video Anthology / 1978-2000 Bruce Springsteen & The E-Street Band - Tokyo 1985 4th & Final Night Bruce Springsteen - Express Bruce Springsteen - Concert Bruce Springsteen - You Better Not Touch. -

Copy UPDATED KAREOKE 2013

Artist Song Title Disc # ? & THE MYSTERIANS 96 TEARS 6781 10 YEARS THROUGH THE IRIS 13637 WASTELAND 13417 10,000 MANIACS BECAUSE THE NIGHT 9703 CANDY EVERYBODY WANTS 1693 LIKE THE WEATHER 6903 MORE THAN THIS 50 TROUBLE ME 6958 100 PROOF AGED IN SOUL SOMEBODY'S BEEN SLEEPING 5612 10CC I'M NOT IN LOVE 1910 112 DANCE WITH ME 10268 PEACHES & CREAM 9282 RIGHT HERE FOR YOU 12650 112 & LUDACRIS HOT & WET 12569 1910 FRUITGUM CO. 1, 2, 3 RED LIGHT 10237 SIMON SAYS 7083 2 PAC CALIFORNIA LOVE 3847 CHANGES 11513 DEAR MAMA 1729 HOW DO YOU WANT IT 7163 THUGZ MANSION 11277 2 PAC & EMINEM ONE DAY AT A TIME 12686 2 UNLIMITED DO WHAT'S GOOD FOR ME 11184 20 FINGERS SHORT DICK MAN 7505 21 DEMANDS GIVE ME A MINUTE 14122 3 DOORS DOWN AWAY FROM THE SUN 12664 BE LIKE THAT 8899 BEHIND THOSE EYES 13174 DUCK & RUN 7913 HERE WITHOUT YOU 12784 KRYPTONITE 5441 LET ME GO 13044 LIVE FOR TODAY 13364 LOSER 7609 ROAD I'M ON, THE 11419 WHEN I'M GONE 10651 3 DOORS DOWN & BOB SEGER LANDING IN LONDON 13517 3 OF HEARTS ARIZONA RAIN 9135 30 SECONDS TO MARS KILL, THE 13625 311 ALL MIXED UP 6641 AMBER 10513 BEYOND THE GREY SKY 12594 FIRST STRAW 12855 I'LL BE HERE AWHILE 9456 YOU WOULDN'T BELIEVE 8907 38 SPECIAL HOLD ON LOOSELY 2815 SECOND CHANCE 8559 3LW I DO 10524 NO MORE (BABY I'MA DO RIGHT) 178 PLAYAS GON' PLAY 8862 3RD STRIKE NO LIGHT 10310 REDEMPTION 10573 3T ANYTHING 6643 4 NON BLONDES WHAT'S UP 1412 4 P.M. -

3 Shadowhunter

THE MORTAL INSTRUMENTS CITY OF BONES CASSANDRA CLARE I have not slept. Between the acting of a dreadful thing And the first motion, all the interim is Like a phantasma, or a hideous dream: The Genius and the mortal instruments Are then in council; and the state of man, Like to a little kingdom, suffers then The nature of an insurrection. —William Shakespeare, Julius Caesar Part 1 DARK DESCENT I sung of Chaos and eternal Night, Taught by the heav—nly Muse to venture down The dark descent, and up to reascend … —John Milton, Paradise Lost 1 PANDEMONIUM “YOU’VE GOT TO BE KIDDING ME,” THE BOUNCER SAID, folding his arms across his massive chest. He stared down at the boy in the red zip-up jacket and shook his shaved head. “You can’t bring that thing in here.” The fifty or so teenagers in line outside the Pandemonium Club leaned forward to eavesdrop. It was a long wait to get into the all-ages club, especially on a Sunday, and not much generally happened in line. The bouncers were fierce and would come down instantly on anyone who looked like they were going to start trouble. Fifteen-year-old Clary Fray, standing in line with her best friend, Simon, leaned forward along with everyone else, hoping for some excitement. “Aw, come on.” The kid hoisted the thing up over his head. It looked like a wooden beam, pointed at one end. “It’s part of my costume.” The bouncer raised an eyebrow. “Which is what?” The boy grinned. -

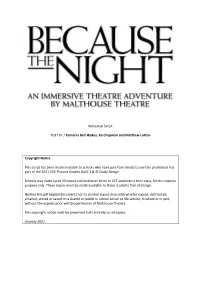

Rehearsal Script TEXT by / Kamarra Bell-Wykes, Ra Chapman and Matthew Lutton Copyright Notice This Script Has Been Made Availabl

Rehearsal Script TEXT BY / Kamarra Bell-Wykes, Ra Chapman and Matthew Lutton Copyright Notice This script has been made available to schools who have purchase tickets to see this production has part of the 2021 VCE Theatre Studies (Unit 3 & 4) Study Design. Schools may make up to 20 copies and distribute them to VCE students in their class, for this express purpose only. These copies must be made available to those students free of charge. Neither this pdf (digital document) nor its printed copies may otherwise be copied, distributed, emailed, stored or saved on a shared or public or school server or file service, in whole or in part, without the express prior written permission of Malthouse Theatre. This copyright notice must be preserved in its entirety on all copies. January 2021 BECAUSE THE NIGHT PROLOGUE The audience are asked to cloak their belongings and leave their phones behind. Audience are given a mask as FOH speaks to them individually: When you enter You can explore every room You can walk wherever you want Whenever want There is no correct way to experience this show Once you enter The only rules are: No speaking No phone And no touching the performers If you need help Or a guide At any time Approach those with the white mask They will help you Audience are invited into the one of the corridors that lead to either the “Gym”, “Royal office” or “The Bedroom” BRIEFING CORRIDOR When all the audience are in the briefing corridors, we hear the sounds of the forest. -

"The Who Sings My Generation" (Album)

“The Who Sings My Generation”—The Who (1966) Added to the National Registry: 2008 Essay by Cary O’Dell Original album Original label The Who Founded in England in 1964, Roger Daltrey, Pete Townshend, John Entwistle, and Keith Moon are, collectively, better known as The Who. As a group on the pop-rock landscape, it’s been said that The Who occupy a rebel ground somewhere between the Beatles and the Rolling Stones, while, at the same time, proving to be innovative, iconoclastic and progressive all on their own. We can thank them for various now- standard rock affectations: the heightened level of decadence in rock (smashed guitars and exploding drum kits, among other now almost clichéd antics); making greater use of synthesizers in popular music; taking American R&B into a decidedly punk direction; and even formulating the idea of the once oxymoronic sounding “rock opera.” Almost all these elements are evident on The Who’s debut album, 1966’s “The Who Sings My Generation.” Though the band—back when they were known as The High Numbers—had a minor English hit in 1964 with the singles “I’m the Face”/”Zoot Suit,” it wouldn’t be until ’66 and the release of “My Generation” that the world got a true what’s what from The Who. “Generation,” steam- powered by its title tune and timeless lyric of “I hope I die before I get old,” “Generation” is a song cycle worthy of its inclusive name. Twelve tracks make up the album: “I Don’t Mind,” “The Good’s Gone,” “La-La-La Lies,” “Much Too Much,” “My Generation,” “The Kids Are Alright,” “Please, Please, Please,” “It’s Not True,” “The Ox,” “A Legal Matter” and “Instant Party.” Allmusic.com summarizes the album appropriately: An explosive debut, and the hardest mod pop recorded by anyone. -

A Long Walk Home: the Role of Class and the Military in the Springsteen Catalogue Michael S

A Long Walk Home: The Role of Class and the Military in the Springsteen Catalogue Michael S. Neiberg United States Army War College and Robert M. Citino National World War II Museum1 Abstract This article analyzes the themes of class and military service in the Springsteen canon. As a member of the baby boom generation who narrowly missed service in Vietnam, Springsteen’s reflection on these heretofore unappreciated themes should not be surprising. Springsteen’s emergence as a musician and American icon coincide with the end of conscription and the introduction of the All-Volunteer Force in 1973. He became an international superstar as Americans were debating the meaning of the post-Vietnam era and the patriotic resurgence of the Reagan era. Because of this context, Springsteen himself became involved in veterans issues and was a voice of protest against the 2003 Iraq War. In a well-known monologue from his Live 1975-85 box set (1986), Bruce Springsteen recalls arguing with his father Douglas about the younger Springsteen’s plans for his future. Whenever Bruce provided inadequate explanations for his life goals, Douglas responded that he could not wait for the Army to “make a man” out of his long-haired, seemingly aimless son. Springsteen 1 Copyright © Michael S. Neiberg and Robert M. Citino, 2016. Michael Neiberg would like to thank Derek Varble, with whom he saw Springsteen in concert in Denver in 2005, for his helpful comments on a draft of this article. Address correspondence to [email protected] or [email protected]. BOSS: The Biannual Online-Journal of Springsteen Studies 2.1 (2016) http://boss.mcgill.ca/ 42 NEIBERG AND CITINO describes his fear as he departed for an Army induction physical in 1968, at the height of domestic discord over the Vietnam War. -

Shinedownthe Biggest Band You've Never Heard of Rocks the Coliseum

JJ GREY & MOFRO DAFOE IS VAN GOGH LOCAL THEATER things to do 264 in the area AT THE PAVILION BRILLIANT IN FILM PRODUCTIONS CALENDARS START ON PAGE 12 Feb. 28-Mar. 6, 2019 FREE WHAT THERE IS TO DO IN FORT WAYNE AND BEYOND THE BIGGEST BAND YOU’VE NEVER SHINEDOWN HEARD OF ROCKS THE COLISEUM ALSO INSIDE: ADAM BAKER & THE HEARTACHE · CASTING CROWNS · FINDING NEVERLAND · JO KOY whatzup.com Just Announced MAY 14 JULY 12 JARED JAMES NICHOLS STATIC-X AND DEVILDRIVER GET Award-winning blues artist known for Wisconsin Death Trip 20th Anniversary energetic live shows and bombastic, Tour and Memorial Tribute to Wayne Static arena-sized rock 'n' roll NOTICED! Bands and venues: Send us your events to get free listings in our calendar! MARCH 2 MARCH 17 whatzup.com/submissions LOS LOBOS W/ JAMES AND THE DRIFTERS WHITEY MORGAN Three decades, thousands of A modern day outlaw channeling greats performances, two Grammys, and the Waylon and Merle but with attitude and global success of “La Bamba” grit all his own MARCH 23 APRIL 25 MEGA 80’S WITH CASUAL FRIDAY BONEY JAMES All your favorite hits from the 80’s and Grammy Award winning saxophonist 90’s, prizes for best dressed named one of the top Contemporary Jazz musicians by Billboard Buckethead MAY 1 Classic Deep Purple with Glenn Hughes MAY 2 Who’s Bad - Michael Jackson Tribute MAY 4 ZoSo - Led Zeppelin Tribute MAY 11 Tesla JUNE 3 Hozier: Wasteland, Baby! Tour JUNE 11 2 WHATZUP FEBRUARY 28-MARCH 6, 2019 Volume 23, Number 31 Inside This Week LIMITED-TIME OFFER Winter Therapy Detailing Package 5 Protect your vehicle against winter Spring Forward grime, and keep it looking great! 4Shinedown Festival FULL INTERIOR AND CERAMIC TOP COAT EXTERIOR DETAILING PAINT PROTECTION Keep your car looking and Offers approximately four feeling like new. -

Rockin' with Reagan, Or the Mainstreaming of Postmodernity Author(S): Lawrence Grossberg Source: Cultural Critique, No

Rockin' with Reagan, or the Mainstreaming of Postmodernity Author(s): Lawrence Grossberg Source: Cultural Critique, No. 10, Popular Narrative, Popular Images (Autumn, 1988), pp. 123- 149 Published by: University of Minnesota Press Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/1354110 Accessed: 25/01/2009 17:46 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=umnpress. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. JSTOR is a not-for-profit organization founded in 1995 to build trusted digital archives for scholarship. We work with the scholarly community to preserve their work and the materials they rely upon, and to build a common research platform that promotes the discovery and use of these resources. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. University of Minnesota Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Cultural Critique. -

Karaoke Mietsystem Songlist

Karaoke Mietsystem Songlist Ein Karaokesystem der Firma Showtronic Solutions AG in Zusammenarbeit mit Karafun. Karaoke-Katalog Update vom: 13/10/2020 Singen Sie online auf www.karafun.de Gesamter Katalog TOP 50 Shallow - A Star is Born Take Me Home, Country Roads - John Denver Skandal im Sperrbezirk - Spider Murphy Gang Griechischer Wein - Udo Jürgens Verdammt, Ich Lieb' Dich - Matthias Reim Dancing Queen - ABBA Dance Monkey - Tones and I Breaking Free - High School Musical In The Ghetto - Elvis Presley Angels - Robbie Williams Hulapalu - Andreas Gabalier Someone Like You - Adele 99 Luftballons - Nena Tage wie diese - Die Toten Hosen Ring of Fire - Johnny Cash Lemon Tree - Fool's Garden Ohne Dich (schlaf' ich heut' nacht nicht ein) - You Are the Reason - Calum Scott Perfect - Ed Sheeran Münchener Freiheit Stand by Me - Ben E. King Im Wagen Vor Mir - Henry Valentino And Uschi Let It Go - Idina Menzel Can You Feel The Love Tonight - The Lion King Atemlos durch die Nacht - Helene Fischer Roller - Apache 207 Someone You Loved - Lewis Capaldi I Want It That Way - Backstreet Boys Über Sieben Brücken Musst Du Gehn - Peter Maffay Summer Of '69 - Bryan Adams Cordula grün - Die Draufgänger Tequila - The Champs ...Baby One More Time - Britney Spears All of Me - John Legend Barbie Girl - Aqua Chasing Cars - Snow Patrol My Way - Frank Sinatra Hallelujah - Alexandra Burke Aber Bitte Mit Sahne - Udo Jürgens Bohemian Rhapsody - Queen Wannabe - Spice Girls Schrei nach Liebe - Die Ärzte Can't Help Falling In Love - Elvis Presley Country Roads - Hermes House Band Westerland - Die Ärzte Warum hast du nicht nein gesagt - Roland Kaiser Ich war noch niemals in New York - Ich War Noch Marmor, Stein Und Eisen Bricht - Drafi Deutscher Zombie - The Cranberries Niemals In New York Ich wollte nie erwachsen sein (Nessajas Lied) - Don't Stop Believing - Journey EXPLICIT Kann Texte enthalten, die nicht für Kinder und Jugendliche geeignet sind.