Banknote Security Features Opinion Editorial Editorial

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Polymer Banknotes

Polymer banknotes Environmental impact of paper and polymer banknotes The Bank of England is responsible for maintaining confidence in the currency, by meeting demand with good quality, genuine banknotes that the public can use with confidence. To support this objective, for the past three years the Bank has been conducting a research project assessing the substrates (materials) that banknotes are printed on with a view to further enhancing counterfeit resilience and increasing the quality of banknotes in circulation. In particular, the Bank has been reviewing the relative merits of printing banknotes on polymer compared with cotton paper. Environmental Study As part of this research, we commissioned an independent study from PE International to assess the environmental impact of the Bank’s current paper banknotes and polymer banknotes. The study followed a Life Cycle Assessment (LCA), which looked at all the stages that a banknote encounters through its life: from first production of raw materials, manufacturing of the banknote materials, printing, distribution into circulation, recirculation (dispensing by ATMs, sorting at regional cash centres) and final return to the Bank of England for destruction and treatment of the waste. The study considered the impact of each stage of the banknote life cycle on 7 environmental indicators, including global warming potential, water and energy usage, ozone creation and environmental toxicity. Polymer showed benefits over cotton paper for all the main phases of the life cycle. For the majority (six from seven) of the indicators covered by the study it has been shown that polymer banknotes have a lower environmental impact than paper banknotes. -

Bank of England Notes: the Switch to Polymer 23

Topical articles Bank of England notes: the switch to polymer 23 Bank of England notes: the switch to polymer By Ronan McClintock and Roy Whymark of the Bank’s Notes Directorate. (1) • The Bank of England is responsible for maintaining confidence in banknotes. • In meeting its banknote issuance responsibilities, the Bank aims to fully exploit innovation. The next £5, £10 and £20 banknotes will be printed on a polymer material. • The switch to polymer will deliver banknotes that are more secure and better quality, and will support confidence in banknotes in the years ahead. Overview The issuance of banknotes is probably the Bank of England’s durable, meaning they will last at least two and a half times most recognisable function. Having first issued banknotes longer than cotton-paper banknotes. And third, the new shortly after it was founded in 1694, the Bank is one of the banknotes will be cleaner, and the public will enjoy the longest-standing issuers of physical money in the world. benefit of better-quality banknotes in their pockets. The Bank of England’s note issuance objectives are to: The new polymer £5 banknote, featuring (i) meet demand for banknotes in the quantities and Sir Winston Churchill, will be unveiled on 2 June, and will denominations required by the public; and (ii) maintain enter circulation in September 2016. Around a year later, confidence in banknotes. The key to maintaining confidence the Bank will launch a new £10 banknote featuring is the distribution of banknotes that are difficult to Jane Austen. A new £20 banknote, featuring a character counterfeit and easy to authenticate. -

Polymer Banknotes Q&A Library

Polymer banknotes Q&A library This Q&A library pulls together a range of information relevant to the introduction of new polymer £5 and £10 notes by the Bank of England. It is primarily intended to provide a useful source of reference for businesses to help prepare for the introduction of the new notes. The library will be updated periodically. Contents What changes are planned for Bank of England banknotes? ................................................................. 2 Why are banknotes changing? ................................................................................................................ 3 When will the new banknotes be issued and the old ones withdrawn? ................................................ 4 Collaborative planning and preparation ................................................................................................. 5 Adapting cash handing machines ........................................................................................................... 6 Recognising and authenticating the new notes ...................................................................................... 7 Properties of polymer banknotes ........................................................................................................... 8 £1 coin and Scottish and Northern Ireland banknotes ........................................................................... 9 Further information ............................................................................................................................. -

Intergraf International Security Printers Conference Copenhagen 22 to 24 April 2015

INFOSECURA A magazine for the security printing industry worldwide, published four times a year by Intergraf in Brussels and mailed to named members of the security printing community, such as security printers, their suppliers, banknote issuing, government and postal authorities as well as police forces in more than 150 countries. Intergraf International Security Printers Conference Copenhagen 22 to 24 April 2015 In this issue: A look at security features on banknotes Poland’s first polymer banknote Designing Norway’s new banknotes Banknotes: Under- or over-featured? Motion’s Rapid move An even livelier Spark and ...security features from G&D and DLR INTERGRAF November 2014- 18th year - Number 62 INFOSECURA EDITORIAL Unforgeable, verifiable and economical? The subject of this issue of Infosecura is the everyday use of currency and thus the banknotes, or more precisely, security fea- national economy, will not be affected. Mo- tures on banknotes. In the last decades, rocco thus gave Landqart’s Durasafe a start. banknotes have become very sophisticated Now Poland, as the second among Europe- and every time a central bank decides to an nations, is testing the water with the 20 issue a new series, not only will the design Złoty banknote printed on Innovia’s Guard- be on an artistically higher level, the security ian. (Rumania was the first European country features will be more advanced, much more to go totally “Polymer”.) difficult to counterfeit and probably more Alternative substrates aside, the idea be- expensive as well. hind the impromptu investigation into the se- Security features are developed by se- curity features used by a handful of different curity printers and banknote paper makers countries was to demonstrate that traditional on the one hand - we are bringing examples security features still hold a large and impor- from De La Rue and Giesecke & Devrient tant place on the world’s currencies. -

Bank of England Decision on the Future Composition of Polymer Banknotes

Press Office Threadneedle Street London EC2R 8AH T 020 7601 4411 F 020 7601 5460 [email protected] www.bankofengland.co.uk 10 August 2017 Bank of England decision on the future composition of polymer banknotes The Bank is today, Thursday 10 August, announcing that after careful and serious consideration and extensive public consultation there will be no change to the composition of polymer used for future banknotes. The new polymer £20 note and future print runs of £5 and £10 notes will continue to be made from polymer manufactured using trace amounts of chemicals, typically less than 0.05%, ultimately derived from animal products. This decision reflects multiple considerations including the concerns raised by the public, the availability of environmentally sustainable alternatives, positions of our Central Bank peers, value for money, as well as the widespread use of animal-derived additives in everyday products, including alternative payment methods. In reaching its decision, the Bank has also taken account of its obligations under the Equality Act 2010. The only currently viable alternative for polymer banknotes is to use chemicals ultimately derived from palm oil. In order to seek the public’s views on both these options, the Bank ran a full public consultation which set out a range of relevant information. The Bank has also conducted outreach meetings with representatives of potentially impacted groups, commissioned technical trials, held commercial discussions and commissioned independent environmental research. 3,554 people responded to our consultation. Of those who expressed a preference, 88% were against the use of animal-derived additives and 48% were against the use of palm oil-derived additives. -

The Future Composition of Polymer Banknotes — Decision Document

August 2017 The future composition of polymer banknotes — decision document Contents 1 Executive summary 5 2 Background 7 3 Technical requirements for polymer manufactured using palm oil-derived additives 9 4 Public consultation 10 5 Sustainability 13 6 Equality considerations 14 7 Costs and commercial implications 16 Box 1 Letter from HM Treasury 17 8 Usage of animal-derived additives in polymer banknotes 18 9 Conclusions 19 Annex Key issues identified in outreach meetings 21 The future composition of polymer banknotes — decision document August 2017 5 1 Executive summary On 10 August 2017, the Bank announced that, following full public consultation, outreach with stakeholders, technical analysis and after careful consideration of viable options, there will be no change to the composition of polymer used for future banknotes. The new polymer £20 banknote, to be issued in 2020, and future print runs of £5 and £10 banknotes will continue to be made from polymer which contains a trace amount, typically less than 0.05%, of additives derived from animal products. This was a difficult decision. It drew on the wide range of evidence gathered and assessed by the Bank over the past few months. This has included a full public consultation, outreach meetings (1) with representatives of potentially impacted groups, technical trials, commercial discussions and independent environmental research. In reaching its decision, the Bank has also taken careful account of its obligations under the Equality Act 2010 (EA 2010). This document summarises the results of the public consultation and the various factors the Bank has had to balance throughout its consideration to reach a decision. -

RBA Annual Report

50 RESERVE BANK OF AUSTRALIA NOTE PRINTING AUSTRALIA AND SECURENCY NOTE PRINTING AUSTRALIA the RBA and now Chief Executive Officer of the Note Printing Australia Limited (NPA), based at Australian Prudential Regulation Authority), Richard Craigieburn in Victoria, is a wholly owned subsidiary Warburton (a non-executive member of the Reserve of the RBA that produces currency notes and other Bank Board), Les Austin (formerly an Assistant security documents for Australia and for export. It Governor of the RBA) and Mark Bethwaite (Chief has been the world pioneer in employing polymer Executive of Australian Business Ltd). John Leckenby in the manufacture of currency notes and now prints has been NPA’s chief executive since 1998. predominantly on Guardian® polymer substrate A major activity for NPA in the past year was manufactured by Securency Pty Ltd (see below). fulfiling an important export contract for notes for The Board of NPA, operating under a broad charter the Bank of Mexico due for issue in late 2002.This from the Reserve Bank Board, comprises chairman involved both design and production of the 20 peso Graeme Thompson (a former Deputy Governor of note.The Bank of Mexico started manufacture of the NPA Polymer Notes Export Orders Year of first issue Customer Denomination Issue 1990 Singapore 50 Dollar Commemorative 1991 Western Samoa 2 Tala Circulating 1991 Papua New Guinea 2 Kina Special Issue Circulating 1993 Kuwait 1 Dinar Commemorative 1994 Indonesia 50 000 Rupiah Special Issue Circulating 1995 Papua New Guinea 2 Kina Special Issue -

Currency Security and Forensics: a Survey

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by AUT Scholarly Commons Currency Security and Forensics: A Survey J. Chambers, W. Yan, A. Garhwal, M. Kankanhalli, e-mail: [email protected] Abstract—By its definition, the word ‘currency’ refers to an agreed medium for exchange, a nation’s currency is the formal medium enforced by the elected governing entity. Throughout history, issuers have faced one common threat: counterfeiting. Despite technological advancements, overcoming counterfeit production remains a distant future. Scientific determination of authenticity requires a deep understanding of the raw materials and manufacturing processes involved. This survey serves as a synthesis of the current literature to understand the technology and the mechanics involved in currency manufacture and security, whilst identifying gaps in the current literature. Ultimately, a robust currency is desired. Keywords—currency forensics, currency security, banknote recognition, substrate analysis, ink analysis, counterfeit currency I. INTRODUCTION Throughout recorded history, as our society has evolved, we have relied on the ability to exchange goods and services with one another. The earliest known medium of exchange was the barter system, although this system still exists, ‘bartering’ has largely been superseded by formal mediums such as coins, banknotes, and more recently, electronic currency. Traditionally, formal mediums of exchange, or ‘currency’ represents an agreed medium both enforced and controlled by the state, today consisting of uniform items holding value. The value held in currency exists purely by the faith entrusted in authenticity, a common challenge currency issuers have faced is securing the design against counterfeits. In many nations, government owned central banks officially known as “reserve banks” manage the nation’s entire monetary policy. -

BOCHK's Banknote Exhibition

31 Oct 2012 “BOCHK’s Banknote Exhibition” organised by Bank of China (Hong Kong) is open to public Bank of China (Hong Kong) Limited (“BOCHK”) is pleased to present “BOCHK’s Banknote Exhibition” starting from 1 November, in celebration of the centenary of its parent bank, Bank of China (“BOC”). With over 200 pieces of exhibits selected from BOCHK’s banknote collections over the century, the exhibition aims to share with the public the unforgettable stories of the monetary development of modern China. The opening ceremony of the exhibition was held today (31 October) at 3/F, Bank of China Tower. The officiating guests of the ceremony include Mr He Guangbei, Vice Chairman and Chief Executive of BOCHK; Mr Lin Wu, Deputy Director of the Liaison Office of the Central People’s Government in the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region (“HKSAR”); Mr Li Yuanming, Deputy Commissioner of the Office of the Commissioner of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the People’s Republic of China (“PRC”) in the HKSAR; and Ms Cynthia Liu, Deputy Director (Culture) of the Leisure and Cultural Services Department of the HKSAR. Addressing the audience at the opening ceremony, Mr He Guangbei, Vice Chairman and Chief Executive of BOCHK, said, “Bank of China, the only domestic bank that has been operating continuously for 100 years, began to issue HKD and MOP banknotes since 1994 and 1995 respectively. We take great pleasure in showing to the public some of its significant banknote series. On top of the precious historical value, the exhibits highlight refined designs: some are delicately crafted while some display general and simple patterns. -

The Use of Polymer in Banco De México Banknotes

Banco de México The use of polymer in Banco de México banknotes Banco de México CONTENTS Background ......................................................................................................................................... 1 Cost-benefit study ............................................................................................................................... 1 Semi-industrial tests and production feasibility ................................................................................. 2 Circulation test .................................................................................................................................... 3 Surveys ................................................................................................................................................ 3 Polymer banknote processing ............................................................................................................. 4 Counterfeiting ..................................................................................................................................... 4 Concluding remarks ............................................................................................................................. 5 Banco de México Background Banco de México’s interest in polymer substrate dates back to 1996 when the Banco de México began experimenting with substrate options available at that time. Three substrata were analyzed, one of them is called DURANOTE (produced by Akro-Mobile), consisting of the -

Portada 2007 A

Banknote Printing at Modern Central Banking: Trends, Costs, and Efficiency Por : Jorge Eduardo Galán Camacho Miguel Sarmiento Paipilla No. 476 2007 - Bogotá - Colombia - Bogotá - Colombia - Bogotá - Colombia - Bogotá - Colombia - Bogotá - Colombia - Bogotá - Colombia - Bogotá - Colombia - Bogotá - Colombia - Bogotá - Colombia - Bogotá - Colombia BANKNOTE PRINTING AT MODERN CENTRAL BANKING: TRENDS, COSTS, AND EFFICIENCY* Jorge Eduardo Galán Camacho Miguel Sarmiento Paipilla♣ Abstract This paper examines trends in banknote printing during the period 2000-2005 for a cross- section of 56 central banks. It was identified that central banks have implemented new strategies to increase efficiency in the production of banknotes, primarily due to the increase in the demand for currency in recent years. One of these strategies has been to involve the private sector through different modalities (e.g. joint ventures, subsidiaries or purchase of banknotes from specialized companies). With the aim to examine the effect of these strategies and other banknote printing features on production costs, a cost function using a panel data model with random effects was estimated. It was identified that the denomination structure, the size of banknotes, and the production method used by central banks have a significant impact over printing costs. Government printing was found to be the most costly method, while involving companies in the process substantially reduces production costs. Based on these results, a non-parametric efficient frontier model was used to measure technical cost efficiency and changes in productivity of central banks. It was found that most central banks have increased its technical efficiency during the period, especially when the private sector has been involved. -

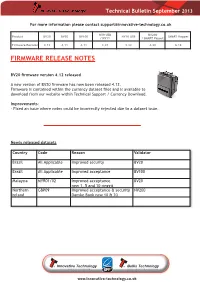

Firmware Release Notes

Technical Bulletin September 2013 For more information please contact [email protected] nV9 USB nV200 Product BV20 BV50 BV100 nV10 USB SmaRT Hopper / nV11 / SmaRT Payout Firmware Revision 4.12 4.11 4.11 3.47 3.32 4.20 6.18 FiRmwaRe ReleaSe noTeS BV20 firmware version 4.12 released A new version of BV20 firmware has now been released 4.12. Firmware is contained within the currency dataset files and is available to download from our website within Technical Support / Currency Download. improvements: - Fixed an issue where notes could be incorrectly rejected due to a dataset issue. newly released datasets Country Code Reason Validator Brazil All Applicable Improved security BV20 Brazil All Applicable Improved acceptance BV100 Malaysia MYR01/02 Improved acceptance BV20 new 1, 5 and 10 ringgit Northern GBP09 Improved acceptance & security NV200 Ireland Danske Bank new 10 & 20 www.innovative-technology.co.uk Technical Bulletin September 2013 For more information please contact [email protected] Validator nV Card Da3 SmaRT Software Product Da3 DPS SmaRT PiPS iTl Drivers manager Utilities Update - €5 Software Revision 1.14 1.1.3 3.3.13 1.4.5 1.4 2.0 1.2 Secure interfacing In today’s advanced technological age we recommend encrypted SSP (eSSP) protocol for all operations. Over the last few years we have seen more frauds against the non-serial protocols such as pulse and parallel and it is our opinion that secure serial protocols such as SSP as now required. Pulse and parallel are inherently insecure and more open to manipulation than serial communications.