Arxiv:1910.06736V1 [Physics.Ins-Det] 9 Oct 2019 Direct Comparisons of European Primary and Secondary Frequency Standards Via Satellite Techniques 2

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Implementing a NTP-Based Time Service Within a Distributed Middleware System

Implementing a NTP-Based Time Service within a Distributed Middleware System Hasan Bulut, Shrideep Pallickara and Geoffrey Fox (hbulut, spallick, gcf)@indiana.edu Community Grids Lab, Indiana University Abstract: Time ordering of events generated by entities existing within a distributed infrastructure is far more difficult than time ordering of events generated by a group of entities having access to the same underlying clock. Network Time Protocol (NTP) has been developed and provided to the public to let them adjust their local computer time from single (multiple) time source(s), which are usually atomic time servers provided by various organizations, like NIST and USNO. In this paper, we describe the implementation of a NTP based time service used within NaradaBrokering, which is an open source distributed middleware system. We will also provide test results obtained using this time service. Keywords: Distributed middleware systems, network time services, time based ordering, NTP 1. Introduction In a distributed messaging system, messages are timestamped before they are issued. Local time is used for timestamping and because of the unsynchronized clocks, the messages (events) generated at different computers cannot be time-ordered at a given destination. On a computer, there are two types of clock, hardware clock and software clock. Computer timers keep time by using a quartz crystal and a counter. Each time the counter is down to zero, it generates an interrupt, which is also called one clock tick. A software clock updates its timer each time this interrupt is generated. Computer clocks may run at different rates. Since crystals usually do not run at exactly the same frequency two software clocks gradually get out of sync and give different values. -

Mutual Benefits of Timekeeping and Positioning

Tavella and Petit Satell Navig (2020) 1:10 https://doi.org/10.1186/s43020-020-00012-0 Satellite Navigation https://satellite-navigation.springeropen.com/ REVIEW Open Access Precise time scales and navigation systems: mutual benefts of timekeeping and positioning Patrizia Tavella* and Gérard Petit Abstract The relationship and the mutual benefts of timekeeping and Global Navigation Satellite Systems (GNSS) are reviewed, showing how each feld has been enriched and will continue to progress, based on the progress of the other feld. The role of GNSSs in the calculation of Coordinated Universal Time (UTC), as well as the capacity of GNSSs to provide UTC time dissemination services are described, leading now to a time transfer accuracy of the order of 1–2 ns. In addi- tion, the fundamental role of atomic clocks in the GNSS positioning is illustrated. The paper presents a review of the current use of GNSS in the international timekeeping system, as well as illustrating the role of GNSS in disseminating time, and use the time and frequency metrology as fundamentals in the navigation service. Keywords: Atomic clock, Time scale, Time measurement, Navigation, Timekeeping, UTC Introduction information. Tis is accomplished by a precise connec- Navigation and timekeeping have always been strongly tion between the GNSS control centre and some of the related. Te current GNSSs are based on a strict time- national laboratories that participate to UTC and realize keeping system and the core measure, the pseudo-range, their real-time local approximation of UTC. is actually a time measurement. To this aim, very good Tese features are reviewed in this paper ofering an clocks are installed on board GNSS satellites, as well as in overview of the mutual advantages between navigation the ground stations and control centres. -

Time and Frequency Transfer in Local Networks by Jir´I Dostál A

Time and Frequency Transfer in Local Networks by Jiˇr´ıDost´al A dissertation thesis submitted to the Faculty of Information Technology, Czech Technical University in Prague, in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor. Dissertation degree study programme: Informatics Department of Computer Systems Prague, August 2018 Supervisor: RNDr. Ing. Vladim´ırSmotlacha, Ph.D. Department of Computer Systems Faculty of Information Technology Czech Technical University in Prague Th´akurova 9 160 00 Prague 6 Czech Republic Copyright c 2018 Jiˇr´ıDost´al ii Abstract This dissertation thesis deals with these topics: network protocols for time distribution, time transfer over optical fibers, comparison of atomic clocks timescales and network time services. The need for precise time and frequency synchronization between devices with microsecond or better accuracy is nowadays challenging task form both scientific and en- gineering point of view. Precise time is also the base of global navigation system (e.g. GPS) and modern telecommunications. There are also new fields of precise time application e.g. finance and high frequency trading. The objective is achieved by two different approaches: precise time and frequency transfer in optical fibers and network time protocols. Theor- etical background and state-of-the-art is described: time and clocks, overview of network time protocols, time and frequency transfer in optical fibers and measurements of time intervals. The main results of our research is presented: IEEE 1588 timestamper, atomic clock comparison, architectures for precise time measurements, running processor on ex- ternal frequency, long distance evaluation of IEEE 1588 performance and time services in CESNET network. -

Time Synchronization in Packet Networks and Influence of Network Devices on Synchronization Accuracy

VOL. 1, NO. 3, SEPTEMBER 2010 Time Synchronization in Packet Networks and Influence of Network Devices on Synchronization Accuracy Michal Pravda 1, Pavel Lafata 1, Jiří Vodrážka 1 1Department of Telecommunication Engineering, Faculty of Electrical Engineering, Czech Technical University in Prague Email: {pravdmic,lafatpav,vodrazka}@fel.cvut.cz Abstract – Time synchronization and its distribution still one of the most popular protocols used for computer time represent a serious problem in modern data networks, synchronization across Internet. SNTP [2] is a simplified especially in packet networks such as the Ethernet. This NTP with worse accuracy. Today, the standard IEEE 1588 article deals with a relatively new synchronization known as PTP (Precision Time Protocol) is increasingly protocol - the IEEE 1588 Precision Clock Synchronization wide-spreading. The first standard, which describes PTP, Protocol (PTP). This protocol reaches the typical accuracy was issued in 2002, but in 2008 a new revision of this better than 100 nanoseconds and uses hierarchical document was published [3]. The main difference between synchronization network infrastructure, which enables to NTP and PTP protocol is the method of their synchronize all devices connected into this network. The implementation. While NTP allows only software first part of the article describes the Precise Time implementation, PTP protocol allows also hardware Protocol, while the second part deals with synchronization implementation. Hardware implementation enables more accuracy measurements for various network topologies accurate determination of arrival and departure time of with different network devices. This paper contains the PTP packet, which is a significant improvement of the presentation of a laboratory synchronization network as synchronization accuracy [4]. -

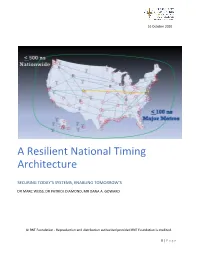

A Resilient National Timing Architecture

16 October 2020 A Resilient National Timing Architecture SECURING TODAY’S SYSTEMS, ENABLING TOMORROW’S DR MARC WEISS, DR PATRICK DIAMOND, MR DANA A. GOWARD © RNT Foundation - Reproduction and distribution authorized provided RNT Foundation is credited. 0 | P a g e A Resilient National Timing Architecture “Everyone in the developed world needs precise time for everything from IT networks to communications. Time is also the basis for positioning and navigation and so is our most silent and important utility.” The Hon. Martin Faga, former Asst Secretary of the Air Force and retired CEO, MITRE Corporation Executive Summary Timing is essential to our economic and national security. It is needed to synchronize networks, for digital broadcast, to efficiently use spectrum, for properly ordering a wide variety of transactions, and to optimize power grids. It is also the underpinning of wireless positioning and navigation systems. America’s over-reliance for timing on vulnerable Global Positioning System (GPS) signals is a disaster waiting to happen. Solar flares, cyberattacks, military or terrorist action – all could permanently disable space systems such as GPS, or disrupt them for significant periods of time. Fortunately, America already has the technology and components for a reliable and resilient national timing architecture that will include space-based assets. This system-of-systems architecture is essential to underpin today’s technology and support development of tomorrow’s systems. This paper discusses the need and rationale for a federally sponsored National Timing Architecture. It proposes a phased implementation using Global Navigation Satellite Systems (GNSS) such as GPS, eLoran, and fiber-based technologies. -

Wireless Clock System

Wireless Clock System Technical Guide BRG Precision Products 600 N. River Derby, Kansas 67037 http://www.DuraTimeClocks.com [email protected] 316-788-2000 Fax: (316) 788-7080 (Patents Pending) Updated: 6/21/2021 Our mission is to offer innovative technology solutions and exceptional service. 1 Table of Contents OVERVIEW ................................................................................................................................................................ 3 DURATIME FEATURES AND OPTIONS .............................................................................................................. 6 PLANNING .................................................................................................................................................................. 9 INSTALLATION......................................................................................................................................................... 9 OPERATION ............................................................................................................................................................. 17 ALARM CONFIGURATION .................................................................................................................................. 21 ALARM CONFIGURATION WORKSHEET ....................................................................................................... 25 MASTER CLOCK CONFIGURATION MENU ................................................................................................... -

Relativity in the Global Positioning System

Relativity in the Global Positioning System Neil Ashby Dept. of Physics, University of Colorado Boulder, CO 80309–0390 U.S.A. [email protected] http://physics.colorado.edu/faculty/ashby_n.html Published on 28 January 2003 www.livingreviews.org/Articles/Volume6/2003-1ashby Living Reviews in Relativity Published by the Max Planck Institute for Gravitational Physics Albert Einstein Institute, Germany Abstract The Global Positioning System (GPS) uses accurate, stable atomic clocks in satellites and on the ground to provide world-wide position and time determination. These clocks have gravitational and motional fre- quency shifts which are so large that, without carefully accounting for numerous relativistic effects, the system would not work. This paper dis- cusses the conceptual basis, founded on special and general relativity, for navigation using GPS. Relativistic principles and effects which must be considered include the constancy of the speed of light, the equivalence principle, the Sagnac effect, time dilation, gravitational frequency shifts, and relativity of synchronization. Experimental tests of relativity ob- tained with a GPS receiver aboard the TOPEX/POSEIDON satellite will be discussed. Recently frequency jumps arising from satellite orbit adjust- ments have been identified as relativistic effects. These will be explained and some interesting applications of GPS will be discussed. c 2003 Max-Planck-Gesellschaft and the authors. Further information on copyright is given at http://www.livingreviews.org/Info/Copyright/. For permission to reproduce the article please contact [email protected]. Article Amendments On author request a Living Reviews article can be amended to include errata and small additions to ensure that the most accurate and up-to-date informa- tion possible is provided. -

Globally Synchronized Time Via Datacenter Networks

Globally Synchronized Time via Datacenter Networks Ki Suh Lee, Han Wang, Vishal Shrivastav, Hakim Weatherspoon Computer Science Department Cornell University kslee,hwang,vishal,[email protected] ABSTRACT croseconds when a network is heavily congested. Synchronized time is critical to distributed systems and network applications in a datacenter network. Unfortu- CCS Concepts nately, many clock synchronization protocols in datacen- •Networks → Time synchronization protocols; Data cen- ter networks such as NTP and PTP are fundamentally lim- ter networks; •Hardware → Networking hardware; ited by the characteristics of packet switching networks. In particular, network jitter, packet buffering and schedul- 1. INTRODUCTION ing in switches, and network stack overheads add non- Synchronized clocks are essential for many network and deterministic variances to the round trip time, which must distributed applications. Importantly, an order of magnitude be accurately measured to synchronize clocks precisely. improvement in synchronized precision can improve perfor- In this paper, we present the Datacenter Time Protocol mance. For instance, if no clock differs by more than 100 (DTP), a clock synchronization protocol that does not use nanoseconds (ns) compared to 1 microsecond (us), one-way packets at all, but is able to achieve nanosecond precision. delay (OWD), which is an important metric for both net- In essence, DTP uses the physical layer of network devices work monitoring and research, can be measured precisely to implement a decentralized clock synchronization proto- due to the tight synchronization. Synchronized clocks with col. By doing so, DTP eliminates most non-deterministic 100 ns precision allow packet level scheduling of minimum elements in clock synchronization protocols. Further, DTP sized packets at a finer granularity, which can minimize con- uses control messages in the physical layer for communicat- gestion in rack-scale systems [23] and in datacenter net- ing hundreds of thousands of protocol messages without in- works [47]. -

Towards Precise Network Measurements

TOWARDS PRECISE NETWORK MEASUREMENTS A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Cornell University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Ki Suh Lee January 2017 c 2017 Ki Suh Lee ALL RIGHTS RESERVED TOWARDS PRECISE NETWORK MEASUREMENTS Ki Suh Lee, Ph.D. Cornell University 2017 This dissertation investigates the question: How do we precisely access and control time in a network of computer systems? Time is fundamental for net- work measurements. It is fundamental in measuring one-way delay and round trip times, which are important for network research, monitoring, and applica- tions. Further, measuring such metrics requires precise timestamps, control of time gaps between messages and synchronized clocks. However, as the speed of computer networks increase and processing delays of network devices de- crease, it is challenging to perform network measurements precisely. The key approach that this dissertation explores to controlling time and achieving precise network measurements is to use the physical layer of the net- work stack. It allows the exploitation of two observations: First, when two physical layers are connected via a cable, each physical layer always generates either data or special characters to maintain the link connectivity. Second, such continuous generation allows two physical layers to be synchronized for clock and bit recovery. As a result, the precision of timestamping can be improved by counting the number of special characters between messages in the physical layer. Further, the precision of pacing can be improved by controlling the num- ber of special characters between messages in the physical layer. -

Time Synchronization in Time-Sensitive Networking

Time Synchronization in Time-Sensitive Networking Stefan Waldhauser, Benedikt Jaeger∗, Max Helm∗ ∗Chair of Network Architectures and Services, Department of Informatics Technical University of Munich, Germany E-Mail: [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] Abstract—Time-Sensitive Networking (TSN) is an update to clock algorithm and message based time synchronization. the existing Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers Then the various PTP device types and message types are (IEEE) Ethernet standard to meet real-time requirements of discussed. The two phases are described in more detail in modern test, measurement, and control systems. TSN uses the rest of the chapter. the Precision Time Protocol (PTP) to synchronize the device Next, in Chapter 3, PTP Version 2 is compared clocks in the system to a reference time. This common sense to another message based time synchronization protocol of time is fundamental to the working of TSN. This paper called Network Time Protocol (NTP) Version 4. Various presents the principles and operation of PTP and compares advantages and disadvantages are discussed. it to the Network Time Protocol (NTP). Finally, Chapter 4 concludes the paper. Index Terms—clock, network time protocol (NTP), precision 2. Precision Time Protocol time protocol (PTP), synchronization, time, time-sensitive networking (TSN) An IEEE 1588 system is a distributed network of PTP enabled devices and possibly non-PTP devices. Non-PTP 1. Introduction devices mainly include conventional switches and routers. An example PTP network can be seen in Fig. 1. In real-time systems, the correctness of a task does not The operation of PTP can be conceptually divided into only rely on the logical correctness of its result but also a two-stage process [6]. -

The Future of Synchronized Time Display for Education, Health Care and Industry

TIME WISETM WIFI SOLUTION The future of synchronized time display for Education, Health Care and Industry National Time & Signal, America’s oldest clock system manufacturer, has integrated WiFi technology with the highest quality manufacturing in the industry to create the TimeWiSE™ family of clock systems. This blend of technologies has resulted in an innovative time keeping platform designed to leverage your existing WiFi infrastructure to conveniently operate and manage your synchronous clock system. Value Summary INNOVATIVE Your WiFi network and our innovative design create a simplified, synchronized Clock system that does not require a master clock, proprietary software or dedicated clock wiring. This creates a flex- ible platform for future growth at significantly reduced costs. CONNECTIVITY Two-way communication easily converts our digital clock into a “timer” through a smart phone, tablet device or computer. The same connectivity can reduce maintenance cost by automatically notifying staff of WiFi signal disruption or errant clock issues. GREEN Your green initiatives are supported by the lowest life cycle cost and lowest energy consumption in the industry. Additionally, the cost of purchasing, changing, and disposing of batteries is elimi- nated. Our design also creates a reliable pathway for future energy alternatives and technology advancements. FLEXIBLE Clock positioning in classrooms and conferencing facilities can easily be modified as requirements change saving dollars for other technology For additional information, or for a free facilities survey, please contact your National Time & Signal representative at 800-326-8456 or [email protected] Tel: (248) 380-6264 • (800) 326-8456 • Fax: (248) 380-6268 • 28045 Oakland Oaks Court • Wixom, MI 48393 www.natsco.net Security No server software installation is required for system operation. -

Ontime Owner's Manual

Figure 1: PoE Cabling Plan ............................................................................................ 6 Figure 2: Analog Clock Mounting Template .............................................................. 7 Figure 3: Analog Clock Cutout Template .................................................................... 8 Figure 4: Analog Clock Double Mount Assembly ...................................................... 9 Figure 5: Mounting Template for 4-Digit Clocks ..................................................... 10 Figure 6: Mounting Template for 6-Digit Clocks ..................................................... 10 Figure 7: Digital Clock Pendant Mounting ............................................................... 11 Figure 8: Digital Clock Cantilever Mounting............................................................ 12 Figure 9: Digital Clock Mounting Kits ....................................................................... 12 Figure 10: Cut-out Template for 4-Digit Clocks ....................................................... 14 Figure 11: Template for 6-Digit Clocks ...................................................................... 14 Figure 12: Data Cable Installation .............................................................................. 15 Figure 13: Clock/Flush Mount Assembly ................................................................. 15 Figure 14: Power Up Sequence ................................................................................... 16 Table 1: Technical Specifications