Lafayette, America's Hero: the Growth of a Legend 1963

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ocm06220211.Pdf

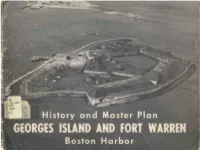

THE COMMONWEALTH OF MASSACHUSETTS--- : Foster F__urcO-lo, Governor METROP--�-��OLITAN DISTRICT COM MISSION; - PARKS DIVISION. HISTORY AND MASTER PLAN GEORGES ISLAND AND FORT WARREN 0 BOSTON HARBOR John E. Maloney, Commissioner Milton Cook Charles W. Greenough Associate Commissioners John Hill Charles J. McCarty Prepared By SHURCLIFF & MERRILL, LANDSCAPE ARCHITECTS BOSTON, MASSACHUSETTS HISTORICAL AND BIOGRAPHICAL CONSULTANT MINOR H. McLAIN . .. .' MAY 1960 , t :. � ,\ �:· !:'/,/ I , Lf; :: .. 1 1 " ' � : '• 600-3-60-927339 Publication of This Document Approved by Bernard Solomon. State Purchasing Agent Estimated cost per copy: $ 3.S2e « \ '< � <: .' '\' , � : 10 - r- /16/ /If( ��c..c��_c.� t � o� rJ 7;1,,,.._,03 � .i ?:,, r12··"- 4 ,-1. ' I" -po �� ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS We wish to acknowledge with thanks the assistance, information and interest extended by Region Five of the National Park Service; the Na tional Archives and Records Service; the Waterfront Committee of the Quincy-South Shore Chamber of Commerce; the Boston Chapter of the United Daughters of the Confederacy; Lieutenant Commander Preston Lincoln, USN, Curator of the Military Order of the Loyal Legion; Mr. Richard Parkhurst, former Chairman of Boston Port Authority; Brigardier General E. F. Periera, World War 11 Battery Commander at Fort Warren; Mr. Edward Rowe Snow, the noted historian; Mr. Hector Campbel I; the ABC Vending Company and the Wilson Line of Massachusetts. We also wish to thank Metropolitan District Commission Police Captain Daniel Connor and Capt. Andrew Sweeney for their assistance in providing transport to and from the Island. Reproductions of photographic materials are by George M. Cushing. COVER The cover shows Fort Warren and George's Island on January 2, 1958. -

Principal Fortifications of the United States (1870–1875)

Principal Fortifications of the United States (1870–1875) uring the late 18th century and through much of the 19th century, army forts were constructed throughout the United States to defend the growing nation from a variety of threats, both perceived and real. Seventeen of these sites are depicted in a collection painted especially for Dthe U.S. Capitol by Seth Eastman. Born in 1808 in Brunswick, Maine, Eastman found expression for his artistic skills in a military career. After graduating from the U.S. Military Academy at West Point, where offi cers-in-training were taught basic drawing and drafting techniques, Eastman was posted to forts in Wisconsin and Minnesota before returning to West Point as assistant teacher of drawing. Eastman also established himself as an accomplished landscape painter, and between 1836 and 1840, 17 of his oils were exhibited at the National Academy of Design in New York City. His election as an honorary member of the academy in 1838 further enhanced his status as an artist. Transferred to posts in Florida, Minnesota, and Texas in the 1840s, Eastman became interested in the Native Americans of these regions and made numerous sketches of the people and their customs. This experience prepared him for his next five years in Washington, D.C., where he was assigned to the commissioner of Indian Affairs and illus trated Henry Rowe Schoolcraft’s important six-volume Historical and Statistical Information Respecting the History, Condition, and Prospects of the Indian Tribes of the United States. During this time Eastman also assisted Captain Montgomery C. Meigs, superintendent of the Capitol Brevet Brigadier General Seth Eastman. -

40 Years of Art

Every year on the Saturday before Memorial Day, art blooms on the grounds of the Tippecanoe County Courthouse in downtown Lafayette, Indiana, as artists display their work. 2013 40 YEARS OF ART 1 2 GATHERING ’ROUND THE FOUNTAIN For 40 years, a group of volunteers has been planning, working, © Journal & Courier © Journal recruiting, fundraising and publicizing, all to bring to life the annual ’Round the Fountain Art Fair. Every year on the Saturday before Memorial Day, art blooms on the grounds of the Tippecanoe County Courthouse in downtown Lafayette, Indiana, as artists display their work. Quality Fine Art A focused mission guides the event: Offer a high-quality fine art fair to the community. ’Round the Fountain Art Fair began in 1974 with 40 artists, $500 in artists’ awards and a commendable turnout. The fair quickly grew in number of artists, and for many years now, held to about 100 from about a dozen or so states. Stellar Successes Accepted through a juried process, these accomplished artists excel in watercolors, acrylics, oils, photography, sculpture, jewelry, clay, ceramics, metal, mixed media and more. All work displayed must be original. The number and amount of awards have increased over the years, too. And some 7,000 visitors attend the admission-free event each year. ’Round the Fountain is a story of achievements—valuing and showcasing the Tippecanoe County Courthouse, bringing people together for an enriching activity, giving artists opportunities to showcase their creativity, attracting new artists each year, and developing a renowned, respected arts event. 3 © Manny Cervantes © Manny 4 HONORING OUR BEGINNINGS Eyeing downtown Lafayette and its betterment, residents floated several ideas during the 1960s and 1970s. -

Memoirs of General Lafayette

Memoirs of General Lafayette Lafayette The Project Gutenberg EBook of Memoirs of General Lafayette, by Lafayette Copyright laws are changing all over the world. Be sure to check the copyright laws for your country before downloading or redistributing this or any other Project Gutenberg eBook. This header should be the first thing seen when viewing this Project Gutenberg file. Please do not remove it. Do not change or edit the header without written permission. Please read the "legal small print," and other information about the eBook and Project Gutenberg at the bottom of this file. Included is important information about your specific rights and restrictions in how the file may be used. You can also find out about how to make a donation to Project Gutenberg, and how to get involved. **Welcome To The World of Free Plain Vanilla Electronic Texts** **eBooks Readable By Both Humans and By Computers, Since 1971** *****These eBooks Were Prepared By Thousands of Volunteers!***** Title: Memoirs of General Lafayette Author: Lafayette Release Date: February, 2005 [EBook #7449] [This file was first posted on May 2, 2003] Edition: 10 Language: English Character set encoding: US-ASCII *** START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK, MEMOIRS OF GENERAL LAFAYETTE *** Stan Goodman, Marvin A. Hodges, Charles Franks, and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team MEMOIRS OF GENERAL LAFAYETTE WITH AN ACCOUNT OF HIS VISIT TO AMERICA, AND OF HIS RECEPTION BY THE PEOPLE OF THE UNITED STATES; FROM HIS ARRIVAL, AUGUST 15TH, TO THE CELEBRATION AT YORKTOWN, OCTOBER 19TH, 1824 by Marie-Joseph-Paul-Yves-Roch-Gilbert du Motier, MARQUIS DE LAFAYETTE [Illustration: Lafayette] _DISTRICT OF MASSACHUSETTS--To wit_: _District Clerk's Office_. -

Guidebook: American Revolution

Guidebook: American Revolution UPPER HUDSON Bennington Battlefield State Historic Site http://nysparks.state.ny.us/sites/info.asp?siteId=3 5181 Route 67 Hoosick Falls, NY 12090 Hours: May-Labor Day, daily 10 AM-7 PM Labor Day-Veterans Day weekends only, 10 AM-7 PM Memorial Day- Columbus Day, 1-4 p.m on Wednesday, Friday and Saturday Phone: (518) 279-1155 (Special Collections of Bailey/Howe Library at Uni Historical Description: Bennington Battlefield State Historic Site is the location of a Revolutionary War battle between the British forces of Colonel Friedrich Baum and Lieutenant Colonel Henrick von Breymann—800 Brunswickers, Canadians, Tories, British regulars, and Native Americans--against American militiamen from Massachusetts, Vermont, and New Hampshire under Brigadier General John Stark (1,500 men) and Colonel Seth Warner (330 men). This battle was fought on August 16, 1777, in a British effort to capture American storehouses in Bennington to restock their depleting provisions. Baum had entrenched his men at the bridge across the Walloomsac River, Dragoon Redoubt, and Tory Fort, which Stark successfully attacked. Colonel Warner's Vermont militia arrived in time to assist Stark's reconstituted force in repelling Breymann's relief column of some 600 men. The British forces had underestimated the strength of their enemy and failed to get the supplies they had sought, weakening General John Burgoyne's army at Saratoga. Baum and over 200 men died and 700 men surrendered. The Americans lost 30 killed and forty wounded The Site: Hessian Hill offers picturesque views and interpretative signs about the battle. Directions: Take Route 7 east to Route 22, then take Route 22 north to Route 67. -

Gazette of the American Friends of Lafayette No

The Gazette of the American Friends of Lafayette No. 88 May 2018 The American Friends of Lafayette with then Governor Terry McAuliffe in front of the Governor's Mansion in Richmond, Virginia Newsletter 1 friendsoflafayette.org Table of Contents Title Page New Members 3 President's Message 4 AFL Annual Meeting- Annapolis 5-6 Lafayette Revisits Central Massachusetts 7-8 AFL at the Governor's Mansion 9-11 Lafayette Day in Virginia 12-14 Lafayette Society and Black History Club Host Presentation 15-18 Fayetteville Lafayette Society Annual Meeting 19 Yorktown 2017 20-25 President Hoffman's Remarks at Yorktown Day 25-30 State of Georgia Proclaims Lafayette Day 31-33 Recent Purchase by Skillman Library Sheds New Light 34 Annual AFL Book Donation 35-36 Lafayette's First Visit to Washington City 37-40 Intersection of Great Men (II) 41 An Update From The Lafayette Trail 42-44 Lafayette inspires leadership training 45-46 A Small French Basque Village Celebrates Yorktown 47-49 Veterans Day 2017 49 Claim Lafayette’s Legacy and Run with It 50-51 Lafayette and LaGrange, GA as Destination 51-52 Lafayette Trivia 53-58 Lafayette's Wedding Feast 59-61 Our Visit To L'Hermione In Rochefort, France 62-70 Robert Selig Completes W3R-US Resource Study for Massachusetts 71-72 Bill Kirchner's Lafayette Collection 73-75 The First Thanksgiving at Chavaniac 76-78 Letter to the Editor 78 Exclusive AFL Member Hotel Deals in France 79 President Macron’s State Visit to Washington D.C. 80-86 A Listing of Lafayette Statues 87-114 Baby Announcement 115 Lafayette Trivia (Answer) 116-118 Newsletter 2 friendsoflafayette.org Welcome New Members! New AFL Members since Sept.16, 2017 (as of May 6, 2018): Active Individual Members: Robert Brown PA Janet Burnet NY Paul Knobel OR Michael LaPaglia NC Frankie Gwinn Moore SC Lindsey Morrison DC Joshua Neiderhiser PA Catherine Paretti NJ R T "Tom" Plott AL Brian Prosser FL Ann Richardson VA Michael E. -

Pierce Butler's Letters to George Cadwalader from Fort Lafayette

Pierce Butler’s letters to George Cadwalader from Fort Lafayette Historical Society of Pennsylvania, George Cadwalader Papers, Collection 1454, Box 411, Folder 3, Correspondence: June-December 1861 Letter #1 Fort Lafayette, Aug. 24, 1861 [Answ. 4 th Sept. 1861] My dear George, After we parted at Camden [New Jersey] on the day of my arrest, nothing occurred until our arrival at New York. The Marshall, his assistant and myself walked to the Aston House, where we stayed about two hours. I wrote a note to Fanny from there, and one to my daughter Fanny at Lenox, to let them know of my arrest. We took a carriage and drove to Fort Hamilton; we reached there at 2 o’c in the morning, and after the necessary ceremonies to gain admittance, we were introduced to Lieut. Col. Martin Burke, 2 nd Artillery, who commands that Fort as well as this one. He received us courteously, and after a brief explanation by the Marshall, I was tranferred in a boat to this Fort. Lieut Chas. O. Wood, 9 th Infantry commands here; Lieut Sterling, 1 st Infantry is second in command; there are about fifty recruits not yet assigned; these, and a sergeant of ordanance constitute the whole force. Mayor [C-y?] [of Baltimore?] is also at Fort Hamilton, but I have not seen him. I found fifteen citizen prisoners here on my arrival on Tuesday morning; I made the sixteenth; four have come in since, to that we have twenty. More are expected. None of those here were taken in arms. -

Baltimore. Saturday, September 14, 1861. Price Two Cents

THE DAILY EXCHANGE. VOL VIII?NO. 1,094. BALTIMORE. SATURDAY, SEPTEMBER 14, 1861. PRICE TWO CENTS. 13ALTIMORE MUSEUM. Together with 165 bbls. Rye Flour, and 241 bbls. Corn f'-r State, afloat?sales 12.000/5)16,000 bushels Canada LIST OF VESSELS IN PORT SH>T. '3 FROM FOIITRESS MONROE. Meal. I East at 31 cts Corn steady at 46% for mixed Western, For Fort Lafayette. chases included in cts. .SHIP*. ; FORTRESS MONROE. Sept. 12.-A Hip of truci* | the above estimate, Mr. Morgan KINK"-MAS GRAIN.?The receipts of Grain have been rather light with sales of II000 bushels afloat at 47 cts. for 4,K)<> WAR ITSMS. ( Marcus Cicero Stanley, a well-known citizen of to /. V Arnold Boninger, (Pras ) Rotterdam?Bros. has pone to to day ha< made others about an IHI'TIA OI'KKA HOUSE' this week, the offerings at the Exchange ot all , bushels car lots; at ihe close buyers had Ronini.cr Norfolk with Mr. I'll lips, of New York, was | equal amount, andcon- RF.SmKr .*F I itE ELITE OF BA DTIMORE Corn do. in withdrawn Mcl.eod, Halmamo, Rotterdam?Ge.vcr k Wilkin* i Vashington, who was retained iI j arrested yesterday, and lakeri to ' I sequently hi- commissions bv this varieties amounting to only about 140.000 The from the market at 46jtf cts. Samples of new Barley some time in his Fort ijifavette time have reached S AFTERNOON' biinhel* Nepiunc. (Breni.) Itahle, Liverpool A Hchnmache.*kCo r.-pi:ciAi. ] bv older of the Secretary of State, 5170,000. -

'Copperhead Gore: Benjamin Wood's Fort Lafayette and Civil War America'

H-Indiana Rodgers on Blondheim, 'Copperhead Gore: Benjamin Wood's Fort Lafayette and Civil War America' Review published on Wednesday, November 1, 2006 Menahem Blondheim, ed. Copperhead Gore: Benjamin Wood's Fort Lafayette and Civil War America. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2006. xi + 291 pp. $21.95 (paper), ISBN 978-0-253-21847-6; $55.00 (cloth), ISBN 978-0-253-34737-4. Reviewed by Thomas E. Rodgers (Department of History, University of Southern Indiana) Published on H-Indiana (November, 2006) The Copperhead Perspective In Copperhead Gore, Menahem Blondheim presents Benjamin's Wood's Civil War novel,Fort Lafayette; or, Love and Secession (1862). He provides an extensive introduction to the novel, a glossary and explanatory notes for various references in it, and two speeches made by Wood in Congress during the war. Benjamin Wood was the editor of theNew York Daily News and a Democratic congressman from New York during the Civil War. Fernando Wood, the mayor of New York City and head of the Mozart Hall faction of the city's Democratic Party, was an older brother who helped his mother raise Benjamin after their father's death. Wood was seen by contemporaries as one of the most notorious Copperheads, a term used by Republicans for northerners who most strongly opposed the Union war effort. In presenting Wood's novel and speeches, Blondheim hopes to give voice to a dissenting wartime minority whose perspective, in his view, has been largely neglected. Blondheim also contends that Wood'sFort Lafayette is "the Civil War's single pacifist novel" (p. 1). -

CDSG Newsletter

CDSGThe Newsletter The Coast Defense Study Group, Inc. — August 2017 Chairman’s Message CDSG Meeting and Tour Calendar Alex Hall Please advise Terry McGovern of any additions or changes at [email protected] Summertime is a busy time for those of us who work in parks, historic sites, and museums. Our coastal fortifications, which we 2018 CDSG Conference love to study and visit, often fit into one or more of these categories. April 25-27, 2018 Although I am very glad our annual conferences are either in the fall Columbia River, OR/WA or spring for good reasons, we miss out experiencing these locations Mark Berhow, [email protected] as most of the public visitors do, as parks, places to recreate, and to learn of the role forts played in local area history and beyond. 2018 CDSG Special Tour Since the last newsletter, I made an overnight trip to Fort Knox, in August 11-19, 2018 Prospect, Maine. This was my first time that far up Maine’s coastline Switzerland and only the second time visiting a fort by motorcycle (Fort Adams Terry McGovern, [email protected] being the first). Only a CDSG conference can get better than that for me! I arrived later in the afternoon and got some nice pictures 2019 CDSG Conference of the main work, exploring the casemates and stopping to watch Chesapeake Bay, VA a bit of a Shakespeare play being put on that evening on the parade Terry McGovern, [email protected] ground. I met David on the operations staff of the Friends of Fort Knox and learned a bit about the work they have done and their 2019 CDSG Special Tour relationship with the State of Maine and running Fort Knox. -

Guide to the Postcard File Ca 1890-Present (Bulk 1900-1940) PR54

Guide to the Postcard File ca 1890-present (Bulk 1900-1940) PR54 The New-York Historical Society 170 Central Park West New York, NY 10024 Descriptive Summary Title: Postcard File Dates: ca 1890-present (bulk 1900-1940) Abstract: The Postcard File contains approximately 61,400 postcards depicting geographic views (New York City and elsewhere), buildings, historical scenes, modes of transportation, holiday greeting and other subjects. Quantity: 52.6 linear feet (97 boxes) Call Phrase: PR 54 Note: This is a PDF version of a legacy finding aid that has not been updated recently and is provided “as is.” It is key-word searchable and can be used to identify and request materials through our online request system (AEON). 2 The New-York Historical Society Library Department of Prints, Photographs, and Architectural Collections PR 054 POSTCARD FILE ca. 1890-present (bulk dates: 1900-1940) 52.6 lin. ft., 97 boxes Series I. Geographic Locations: United States Series II. Geographic Locations: International Series III. Subjects Processed by Jennifer Lewis January 2002 PR 054 3 Provenance The Postcard File contains cards from a variety of sources. Larger contributions include 3,340 postcard views of New York City donated by Samuel V. Hoffman in 1941 and approximately 10,000 postcards obtained from the stock file of the Brooklyn-based Albertype Company in 1953. Access The collection open to qualified researchers. Portions of the collection that have been photocopied or microfilmed will be brought to the researcher in that format; microfilm can be made available through Interlibrary Loan. Photocopying Photocopying will be undertaken by staff only, and is limited to twenty exposures of stable, unbound material per day. -

Entreaty for Help from a Political Prisoner

SCQ Patricia A. Kaufmann EntreatyEntreaty forfor HelpHelp fromfrom aa PoliticalPolitical PrisonerPrisoner adison Y. Johnson was an attorney engaged for the defense in a murder trial in Galena, Illinois, on August 28, 1862, when he was seized in the court house and taken to the passenger train depot. From there he was taken to Chicago, where he wasM confined for two days, then taken to New York City, and imprisoned in what was known as the “Inner Temple,” on Elm street. He was confined there for twenty-four hours, then taken to Fort Hamilton for processing. Johnson was conveyed by boat to Fort Lafayette in New York Harbor, where he was detained as a political prisoner for two months.1 (Figure 2) Figure 4. Cover from political prisoner M.Y. Johnson to Darius Hunkins, “Examined D.D. Per- kins, Lt. Col. Comdg Fort Dela- ware Dec 8th [1862].” It bears a 3¢ rose 1861 issue postmarked Delaware City, Del., in blue. Washington, D.C.’s Willard’s Hotel—where Abraham Lincoln slept the night before his inauguration in January 1861 3030 • •Kelleher’s Kelleher’s Stamp Stamp Collector’s Collector’s Quarterly Quarterly • •Second Second Quarter Quarter 2017 2017 Photo taken in 1919. Kelleher’s Stamp Collector’s Quarterly • Second Quarter 2017 • 31 Subsequently, Johnson was transferred to Fort Delaware, a military fortification in the Delaware Bay on Pea Patch Island, there con- fined until released. (Figure 3) The cover shown in Figure 4 is addressed in the hand on M. Y. Johnson to Darius Hunkins, Esq., Care of Willards Hotel, Washington City, D.C.