FEDERAL STEWARDSHIP of CONFEDERATE DEAD This Page Intentionally Left Blank

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download Download

Social Life and Social Services in Indianapolis Networks During the Gilded Age and Progressive Era KATHERINE BADERTSCHER ABSTRACT: In late nineteenth-century Indianapolis, a group of citizens, united by social networks, dominated the gov- ernance and management of the city’s social services for several decades. The tight-knit network of men and women worked together at the center of social and philanthropic life. Since its inception in 1879, the Charity Organization Society of Indianapolis (COS) wielded virtual control over social welfare—making it one of the most progressive and powerful philanthropic organizations in the country. An influ- ential coterie of men and women governed, donated to, and volunteered for the COS and many of its sub-agencies. Then, as now, social networks are as essential for us to understand as social entrepreneurs and charismatic leaders. KEYWORDS: Charity Organization Society; social networks; social life; Progressive Era; Indianapolis; philanthropy n nineteenth-century Indianapolis, a group of citizens, united by social Inetworks, dominated the governance and management of the city’s social services for several decades. Social networks build and sustain communi- ties, as groups of citizens solve community problems and work together toward a notion of the common good. Such networks facilitate access to information, enhance individuals’ influence, and create solidarity that INDIANA MAGAZINE OF HISTORY, 113 ( December 2017). © 2017, Trustees of Indiana University. doi: 10.2979/indimagahist.113.4.01 272 INDIANA MAGAZINE OF HISTORY reinforces cultural norms.1 The organized charity movement of Gilded Age and Progressive Era Indianapolis provide an important example of how social networks established and strengthened the community’s prevailing cultural norms. -

The Battle to Interpret Arlington House, 1921–1937,” by Michael B

Welcome to a free reading from Washington History: Magazine of the Historical Society of Washington, D.C. As we chose this week’s reading, news stories continued to swirl about commemorative statues, plaques, street names, and institutional names that amplify white supremacy in America and in DC. We note, as the Historical Society fulfills its mission of offering thoughtful, researched context for today’s issues, that a key influence on the history of commemoration has come to the surface: the quiet, ladylike (in the anachronistic sense) role of promoters of the southern “Lost Cause” school of Civil War interpretation. Historian Michael Chornesky details how federal officials fended off southern supremacists (posing as preservationists) on how to interpret Arlington House, home of George Washington’s adopted family and eventually of Confederate commander Robert E. Lee. “Confederate Island upon the Union’s ‘Most Hallowed Ground’: The Battle to Interpret Arlington House, 1921–1937,” by Michael B. Chornesky. “Confederate Island” first appeared in Washington History 27-1 (spring 2015), © Historical Society of Washington, D.C. Access via JSTOR* to the entire run of Washington History and its predecessor, Records of the Columbia Historical Society, is a benefit of membership in the Historical Society of Washington, D.C. at the Membership Plus level. Copies of this and many other back issues of Washington History magazine are available for browsing and purchase online through the DC History Center Store: https://dchistory.z2systems.com/np/clients/dchistory/giftstore.jsp ABOUT THE HISTORICAL SOCIETY OF WASHINGTON, D.C. The Historical Society of Washington, D.C., is a non-profit, 501(c)(3), community-supported educational and research organization that collects, interprets, and shares the history of our nation's capital in order to promote a sense of identity, place and pride in our city and preserve its heritage for future generations. -

United Confederate Veterans Association Records

UNITED CONFEDERATE VETERANS ASSOCIATION RECORDS (Mss. 1357) Inventory Compiled by Luana Henderson 1996 Louisiana and Lower Mississippi Valley Collections Special Collections, Hill Memorial Library Louisiana State University Libraries Baton Rouge, Louisiana Revised 2009 UNITED CONFEDERATE VETERANS ASSOCIATION RECORDS Mss. 1357 1861-1944 Special Collections, LSU Libraries CONTENTS OF INVENTORY SUMMARY .................................................................................................................................... 3 BIOGRAPHICAL/HISTORICAL NOTE ...................................................................................... 4 SCOPE AND CONTENT NOTE ................................................................................................... 6 LIST OF SUBGROUPS AND SERIES ......................................................................................... 7 SUBGROUPS AND SERIES DESCRIPTIONS ............................................................................ 8 INDEX TERMS ............................................................................................................................ 13 CONTAINER LIST ...................................................................................................................... 15 APPENDIX A ............................................................................................................................... 22 APPENDIX B ............................................................................................................................. -

The History of the Land of Indian Hill

513-721-LAND(5263) [email protected] The History of the Land of Indian Hill Blome Road Bridge c. 1888 Blome Road Bridge was built in 1888 by The Queen City Bridge Company. It is a one lane bridge that crosses over Sycamore Creek. It is the only surviving bridge by The Queen City Bridge Company. Blome Bridge is 127 years old. It was created with a pin connected Pratt through truss bridge, making it unusual in design. It was composed of six panels, most noted for slight skew. The Queen City Bridge Company used pipe railing that passes through the vertical members and also the end post. It was great for horse and wagon passage. The Blome Road Bridge was restored by Hamilton County in 1990. Hamilton County built a beam bridge underneath the truss bridge so not to alter the original design and materials. Buckingham House c. 1790 The Buckingham House is one of the few farm houses left in Indian Hill; built during the Civil War. The Buckingham’s came to Ohio in 1790. They purchased 1,100 acres of land in Indian Hill, known as Camp Dennison. They owned and operated mills on the Little Miami River. The Buckingham home is surrounded by 13 acres of land called Bonnell Park. Indian Hill Bridges There are two bridges in Indian Hill. One is located at Shawnee Run Road and State Route 126. This bridge was used by Pennsylvania Railroad trains to move cargo. Today the remnants of the bridge can still be seen by bicyclist and joggers. -

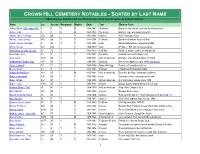

Crown Hill Cemetery Notables - Sorted by Last Name

CROWN HILL CEMETERY NOTABLES - SORTED BY LAST NAME Most of these notables are included on one of our historic tours, as indicated below. Name Lot Section Monument Marker Dates Tour Claim to Fame Achey, David (Dad, see p 440) 7 5 N N 1838-1861 Skeletons Gambler who met his “just end” when murdered Achey, John 7 5 N N 1840-1879 Skeletons Gambler who was hung for murder Adams, Alice Vonnegut 453 66 Y 1917-1958 Authors Kurt Vonnegut’s sister Adams, Justus (more) 115 36 Y Y 1841-1904 Politician Speaker of Indiana House of Rep. Allison, James (mansion) 2 23 Y Y 1872-1928 Auto Allison Engineering, co-founder of IMS Amick, George 723 235 Y 1924-1959 Auto 2nd place 1958 500, died at Daytona Armentrout, Lt. Com. George 12 12 Y 1822-1875 Civil War Naval Lt., marble anchor on monument Armstrong, John 10 5 Y Y 1811-1902 Founders Had farm across Michigan road Artis, Lionel 1525 98 Y 1895-1971 African American Manager of Lockfield Gardens 1937-69 Aufderheide’s Family, May 107 42 Y Y 1888-1972 Musician She wrote ragtime in early 1900s (her music) Ayres, Lyman S 19 11 Y Y 1824-1896 Names/Heritage Founder of department stores Bacon, Hiram 43 3 Y 1801-1881 Heritage Underground RR stop in Indpls Bagby, Robert Bruce 143 27 N 1847-1903 African American Ex-slave, principal, newspaper publisher Baker, Cannonball 150 60 Y Y 1882-1960 Auto Set many cross-country speed records Baker, Emma 822 37 Y 1885-1934 African American City’s first black female police 1918 Baker, Jason 1708 97 Y 1976-2001 Heroes Marion County Deputy killed in line of duty Baldwin, Robert “Tiny” 11 41 Y 1904-1959 African American Negro Nat’l League 1920s Ball, Randall 745 96 Y 1891-1945 Heroes Fireman died on duty Ballard, Granville Mellen 30 42 Y 1833-1926 Authors Poet, at CHC ded. -

Camp Douglas News Committed to the Preservation of Chicago History

Camp Douglas News Committed to the Preservation of Chicago History Camp Douglas Restoration Foundation Chicago, Illinois Winter 2012 Volume 3, Issue 4 Project Phases: Camp Douglas Restoration Foundation—Latest News Awareness and Support: place the artifacts within VIRTUAL CAMP 2010-2013 historic perspectives. DOUGLAS PROJECT CONTINUES Site Location and Site GRIFFIN FUNERAL HOME The students from IIT Planning: 2012 TO BE DEVELOPED presented their results Prologue, Inc. announced November 30 as part of plans to develop an Archaeological Investigation: the IPRO Day at IIT. alternate school, 2012-2013 They, along with 29 community center and Civil other IPRO teams, War museum on the site of Virtual Camp Douglas: 2013 were judged on a the former Griffin Funeral video, table top display Home, 3232 S. King Drive. and oral presentation Construction: 2013-14 The announcement was to a panel of judges. made by Dr. Nancy Jackson, Executive Director of Prologue which Preliminary views of the camp map, story operates alternate schools in Chicago providing boards and web site were impressive. Students educational opportunities to school drop-outs working on the story boards have conducted who are not eligible to reenter the public Civil War research into stories about camp life in schools. The Foundation has been in contact preparation for videos to be produced. Mapping with Dr. Jackson and is cooperating with them Bits & Pieces of Camp Douglas is nearly completed and the on the development of the museum. web site brings stories and mapping together. Ernest Griffin and his Next semester the project will continue at IIT Civil War Units family, after his death in 1995 under the leadership of Professor Laura Batson. -

Department of Ohio Sons of Union Veterans of the Civil

Department of Ohio Department of Ohio Officers 2005-2006 Sons of Union Veterans of the Commander Raymond C. Nagel Civil War Senior Vice Commander Gregory A. Kenney Junior Vice Commander Ken Freshley Secretary/Treasurer PDC David V. Medert Department Council PDC Bradley A. Tilton PDC James H. Houston, Jr. Christopher Greene Personal Aide PDC James H. Houston, Jr.. Chief of Staff Robert W. Davis Counselor Christopher Greene. Patriotic Instructor Christopher Greene Graves Registration Officer Kent Dorr Eagle Scout Coordinator Bradley A. Tilton Civil War Memorials Officer Donald L. Grant Signals Officer Ken Freshley Historian PDC Robert J. Wolz Genealogist Daniel J. Spellman Chaplain Howard T. Frost Guard James L. Yahle Guide James Oiler Color Guard Kirby Bauman GAR Highway Officer Ken Freshley Mark D. Britton Camp Chase Rep. Robert W. Davis th Fraternal Relations Robert W. Davis 124 Annual Encampment PCinC Richard L. Greenwalt June 16-18, 2006 PDC James H. Houston, Jr. Mount Union College Department Encampment PCinC Richard L.Greenwalt Ohio Veterans Home PDC Jon B. Silvis Alliance, Ohio Christmas Committee Mark D. Britton Camps of the Department of Ohio Schedule Gov. William Dennison Camp 1 Columbus Gen. Benjamin D. Fearing Camp 2 Friday, June 16 Marietta Brig. Gen. Samuel A. Gilbert Camp 5 Springfield Noon Room Registration Brooks-Grant Camp 7 Middleport 5:00 pm Dinner Pvt. Valentin Keller Camp 8 7:00 pm Campfire Fairfield Gen. William Lytle Camp 10 Cincinnati Saturday, June 17 Gen. William McLaughlin Camp 12 Mansfield Vienna Camp 26 New Boston 8:00 am Breakfast Phillip Triem Camp 43 9:00 am Joint Opening Salem Given Camp 51 10:00 am Business Session Wooster Noon Lunch Gen. -

Civil War Generals Buried in Spring Grove Cemetery by James Barnett

Spring Grove Cemetery, once characterized as blending "the elegance of a park with the pensive beauty of a burial-place," is the final resting- place of forty Cincinnatians who were generals during the Civil War. Forty For the Union: Civil War Generals Buried in Spring Grove Cemetery by James Barnett f the forty Civil War generals who are buried in Spring Grove Cemetery, twenty-three had advanced from no military experience whatsoever to attain the highest rank in the Union Army. This remarkable feat underscores the nature of the Northern army that suppressed the rebellion of the Confed- erate states during the years 1861 to 1865. Initially, it was a force of "inspired volunteers" rather than a standing army in the European tradition. Only seven of these forty leaders were graduates of West Point: Jacob Ammen, Joshua H. Bates, Sidney Burbank, Kenner Garrard, Joseph Hooker, Alexander McCook, and Godfrey Weitzel. Four of these seven —Burbank, Garrard, Mc- Cook, and Weitzel —were in the regular army at the outbreak of the war; the other three volunteered when the war started. Only four of the forty generals had ever been in combat before: William H. Lytle, August Moor, and Joseph Hooker served in the Mexican War, and William H. Baldwin fought under Giuseppe Garibaldi in the Italian civil war. This lack of professional soldiers did not come about by chance. When the Constitutional Convention met in Philadelphia in 1787, its delegates, who possessed a vast knowledge of European history, were determined not to create a legal basis for a standing army. The founding fathers believed that the stand- ing armies belonging to royalty were responsible for the endless bloody wars that plagued Europe. -

Breaking Bad and Cinematic Television

temp Breaking Bad and Cinematic Television ANGELO RESTIVO Breaking Bad and Cinematic Television A production of the Console- ing Passions book series Edited by Lynn Spigel Breaking Bad and Cinematic Television ANGELO RESTIVO DUKE UNIVERSITY PRESS Durham and London 2019 © 2019 Duke University Press All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America on acid- free paper ∞ Typeset in Warnock and News Gothic by Tseng Information Systems, Inc. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Restivo, Angelo, [date] author. Title: Breaking bad and cinematic television / Angelo Restivo. Description: Durham : Duke University Press, 2019. | Series: Spin offs : a production of the Console-ing Passions book series | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: LCCN 2018033898 (print) LCCN 2018043471 (ebook) ISBN 9781478003441 (ebook) ISBN 9781478001935 (hardcover : alk. paper) ISBN 9781478003083 (pbk. : alk. paper) Subjects: LCSH: Breaking bad (Television program : 2008–2013) | Television series— Social aspects—United States. | Television series—United States—History and criticism. | Popular culture—United States—History—21st century. Classification: LCC PN1992.77.B74 (ebook) | LCC PN1992.77.B74 R47 2019 (print) | DDC 791.45/72—dc23 LC record available at https: // lccn.loc.gov/2018033898 Cover art: Breaking Bad, episode 103 (2008). Duke University Press gratefully acknowledges the support of Georgia State University’s College of the Arts, School of Film, Media, and Theatre, and Creative Media Industries Institute, which provided funds toward the publication of this book. Not to mention that most terrible drug—ourselves— which we take in solitude. —WALTER BENJAMIN Contents note to the reader ix acknowledgments xi Introduction 1 1 The Cinematic 25 2 The House 54 3 The Puzzle 81 4 Just Gaming 116 5 Immanence: A Life 137 notes 159 bibliography 171 index 179 Note to the Reader While this is an academic study, I have tried to write the book in such a way that it will be accessible to the generally educated reader. -

HARDTACK Indianapolis Civil War Round Table Newsletter

1 HARDTACK Indianapolis Civil War Round Table Newsletter http://indianapoliscwrt.org/ October 8, 2012 at 7:30 p.m. Meeting at Indiana History Center Auditorium 450 West Ohio Street The Plan of the Day “An Irrepressible Conflict”: Civil War Rioting in Cincinnati, 1862 Cincinnati in 1862, lithograph in Harper’s Weekly In July of 1862, Irish workers in Cincinnati rioted to keep black workers from laboring on the docks, and attempted to “clean out” African American residential sections of the city. A precursor to the more infamous New York draft riots of 1863, the violence was triggered by the prospect of a draft and the rumored arming of black soldiers. Fearing that their jobs would be threatened by emancipation and an influx of black workers, immigrant laborers tried to establish themselves as true citizens and African Americans as interlopers. During the Civil War, as at other times in the nation’s history, black men staked their claims to citizenship on their loyal labor and their armed service—not just in federal armies, but in defense of their homes and livelihoods. When black workers organized in self-defense, white Cincinnatians quickly formed militia units in response. This wartime rioting followed patterns of antebellum riots, but the emancipation of African Americans and their military service during the war created a clear turning point in black demands for social citizenship. JOIN US BEFORE THE MEETING AT SHAPIRO’S DELI! All ICWRT members and guests are invited to join us at 5:30 P.M. at Shapiro’s Delicatessen, 808 S. Meridian St. (just south of McCarty Street) before the meeting to enjoy dinner and fellowship. -

On MONDAY, September 24, the Roundtable Welcomes MRRT Member Rufus K

VOL. LII, NO. 9 Michigan Regimental Round Table Newsletter—Page 1 September 2012 Last call to sign-up for the October 27-28 field trip to the battlefields of First and Second Bull Run. Should you have the time and inclination to join the thirty one members slated to go, contact one of the trip coordinators. You can find their contact information and all other particulars on our website at: www.farmlib.org/mrrt/annual_fieldtrip.html. On MONDAY, September 24, the Roundtable welcomes MRRT member Rufus K. Barton, III. Rufus will discuss the “Missouri Surprise of 1864, the battle of Fort Davidson”. The crucial struggle for control of Missouri has been neglected by most Civil War historians over the years. Rufus will explain that while President Lincoln said he had to have Kentucky, the Union occupation of Missouri saved his “bacon”. The Battle of Fort Davidson on September 27, 1864 was the opening engagement of Confederate Major General Sterling Price’s raid to “liberate” his home state. The battle’s outcome played a key role in the final Union victory in Missouri. Rufus grew up in the St. Louis, Missouri area and his business opportunities brought him to Michigan in 1975. Rufus was also an U.S. Army Lieutenant and a pilot for 30 years. Studying the Civil War is one of his hobbies. The MRRT would like to thank William Cottrell for his exceptional presentation, “Lincoln’s Position on Slavery—A Work In Progress”. Bill presented the MRRT a thoughtful and well researched presentation on the progression of Abraham Lincoln’s thinking on the slavery question and how it culminated in action during his Presidency. -

The Flag to Fly No More? Confederate References 1889 and Marks Where 800 Come Under Fire After Residents Volunteered to Join S.C

Vol. 11, No. 29 Alexandria’s only independent hometown newspaper JULY 16, 2015 The flag to fly no more? Confederate references 1889 and marks where 800 come under fire after residents volunteered to join S.C. shooting the Army of Northern Vir- BY ERICH WAGNER ginia. And a plaque adorns As one of the biggest the Marshall House — now state-sanctioned reminders Hotel Monaco — at the corner of the U.S. Civil War — of King and South Pitt streets, the Confederate battle flag commemorating where hotel — was removed from the owner James W. Jackson shot grounds of South Carolina’s and killed Union Col. Elmer E. PHOTO/GEOFF LIVINGSTON 266 YEARS YOUNG The Potomac River is lit up by fireworks capitol last week, the debate Ellsworth before being shot by at the conclusion of Alexandria’s 266th birthday celebrations and over references to southern other Union troops during their the United States’ 239th birthday last weekend. The evening’s secession in Alexandria was takeover of the city. event at Oronoco Bay Park saw Mayor Bill Euille and city coun- cilors distribute birthday cake before the Alexandria Symphony just heating up. Lance Mallamo, director of Orchestra performed, among other highlights. The shooting deaths of the Office of Historic Alexan- nine people at a Bible study dria, said the idea for the Ap- meeting at a historic black pomattox statue came from Ed- church in Charleston, S.C. last gar Warfield, the last surviving Shots fired calls in month has caused an ground- member of the group, in 1885. swell in discussions about the “After the war, he came back prominence of the Confed- to Alexandria and became a Alexandria down erate flag across the South.