Dancing Without Bodies: Pedagogy and Performance in Digital Spaces

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Is a Genre of Dance Performance That Developed During the Mid-Twentieth

Contemporary Dance Dance 3-4 -Is a genre of dance performance that developed during the mid-twentieth century - Has grown to become one of the dominant genres for formally trained dancers throughout the world, with particularly strong popularity in the U.S. and Europe. -Although originally informed by and borrowing from classical, modern, and jazz styles, it has since come to incorporate elements from many styles of dance. Due to its technical similarities, it is often perceived to be closely related to modern dance, ballet, and other classical concert dance styles. -It also employs contract-release, floor work, fall and recovery, and improvisation characteristics of modern dance. -Involves exploration of unpredictable changes in rhythm, speed, and direction. -Sometimes incorporates elements of non-western dance cultures, such as elements from African dance including bent knees, or movements from the Japanese contemporary dance, Butoh. -Contemporary dance draws on both classical ballet and modern dance -Merce Cunningham is considered to be the first choreographer to "develop an independent attitude towards modern dance" and defy the ideas that were established by it. -Cunningham formed the Merce Cunningham Dance Company in 1953 and went on to create more than one hundred and fifty works for the company, many of which have been performed internationally by ballet and modern dance companies. -There is usually a choreographer who makes the creative decisions and decides whether the piece is an abstract or a narrative one. -Choreography is determined based on its relation to the music or sounds that is danced to. . -

The Social Media Marketing Book Dan Zarrella

the social media marketing book Dan Zarrella Beijing · Cambridge · Farnham · Köln · Sebastopol · Taipei · Tokyo The Social Media Marketing Book by Dan Zarrella Copyright © 2010 Dan Zarrella. Printed in Canada. Published by O’Reilly Media, Inc., 1005 Gravenstein Highway North, Sebastopol, CA 95472. O’Reilly books may be purchased for educational, business, or sales promotional use. Online editions are also available for most titles (http://my.safaribooksonline.com). For more information, contact our corporate/institutional sales department: (800) 998-9938 or [email protected]. Editor: Laurel R. T. Ruma Indexer: Julie Hawks Production Editor: Rachel Monaghan Interior Designer: Ron Bilodeau Copyeditor: Audrey Doyle Cover Designer: Monica Kamsvaag Proofreader: Sumita Mukherji Illustrator: Robert Romano Printing History: November 2009: First Edition. While every precaution has been taken in the preparation of this book, the publisher and author assume no responsibility for errors or omissions, or for damages resulting from the use of the information contained herein. This book presents general information about technology and services that are constantly changing, and therefore it may contain errors and/or information that, while accurate when it was written, is no longer accurate by the time you read it. Some of the activities discussed in this book, such as advertising, fund raising, and corporate communications, may be subject to legal restrictions. Your use of or reliance on the information in this book is at your own risk and the author and O’Reilly Media, Inc., disclaim responsibility for any resulting damage or expense. The content of this book represents the views of the author only, and does not represent the views of O’Reilly Media, Inc. -

Queens College Student Choreography Showcase 2021

Queens College Student Choreography Showcase 2021 About the Choreographers Alisha Anderson is a professional dancer who works every day to fulfill the highest expression of herself as a human being and an artist. Alisha has studied various genres of dance for over 20 years and specializes in tap, Afrobeat and African dance. She began her dance career at her family owned dance school, Dance Arts Repertory Theater, which had a well known company called Yori that specialized in African dance; and inspired her to become a professional African dancer. Alisha has studied under Randi Lloyd, Lancelot Theobald, Shandella Molly, Jewel Love, Chet and many more. She is currently attending Queens College where she is graduating with a Minor in Dance and a MaJor in Education. Alisha has traveled to Ghana, Senegal and other countries in West Africa to further her studies in African dance. Alisha has performed professionally with Salsa Ache which is a salsa and Afro Caribbean dance company, and currently performs with two of the top African dance companies in New York City, Harambee and Bambara. In 2014 Alisha joined Harambee which is directed by Shandella Molly and located in Bronx, NY. With Harambee Alisha has performed for the African American Museum, Nick Cannon, Vice the TV show and many more. In 2015 she joined Bambara which is directed by Jewel Love, and with the company she has performed for the Tira Banks show, Dance Africa (BAM), numerous African festivals, weddings and much more. Alisha began her teaching career at Layla Dance and Drum school where she has taught for the past three years and enjoys working with the students. -

Indian Classical Dance Is a Relatively New Umbrella Term for Various Codified Art Forms Rooted in Natya, the Sacred Hindu Musica

CLASSICAL AND FOLK DANCES IN INDIAN CULTURE Palkalai Chemmal Dr ANANDA BALAYOGI BHAVANANI Chairman: Yoganjali Natyalayam, Pondicherry. INTRODUCTION: Dance in India comprises the varied styles of dances and as with other aspects of Indian culture, different forms of dances originated in different parts of India, developed according to the local traditions and also imbibed elements from other parts of the country. These dance forms emerged from Indian traditions, epics and mythology. Sangeet Natak Akademi, the national academy for performing arts, recognizes eight distinctive traditional dances as Indian classical dances, which might have origin in religious activities of distant past. These are: Bharatanatyam- Tamil Nadu Kathak- Uttar Pradesh Kathakali- Kerala Kuchipudi- Andhra Pradesh Manipuri-Manipur Mohiniyattam-Kerala Odissi-Odisha Sattriya-Assam Folk dances are numerous in number and style, and vary according to the local tradition of the respective state, ethnic or geographic regions. Contemporary dances include refined and experimental fusions of classical, folk and Western forms. Dancing traditions of India have influence not only over the dances in the whole of South Asia, but on the dancing forms of South East Asia as well. In modern times, the presentation of Indian dance styles in films (Bollywood dancing) has exposed the range of dance in India to a global audience. In ancient India, dance was usually a functional activity dedicated to worship, entertainment or leisure. Dancers usually performed in temples, on festive occasions and seasonal harvests. Dance was performed on a regular basis before deities as a form of worship. Even in modern India, deities are invoked through religious folk dance forms from ancient times. -

Types of Dance Styles

Types of Dance Styles International Standard Ballroom Dances Ballroom Dance: Ballroom dancing is one of the most entertaining and elite styles of dancing. In the earlier days, ballroom dancewas only for the privileged class of people, the socialites if you must. This style of dancing with a partner, originated in Germany, but is now a popular act followed in varied dance styles. Today, the popularity of ballroom dance is evident, given the innumerable shows and competitions worldwide that revere dance, in all its form. This dance includes many other styles sub-categorized under this. There are many dance techniques that have been developed especially in America. The International Standard recognizes around 10 styles that belong to the category of ballroom dancing, whereas the American style has few forms that are different from those included under the International Standard. Tango: It definitely does take two to tango and this dance also belongs to the American Style category. Like all ballroom dancers, the male has to lead the female partner. The choreography of this dance is what sets it apart from other styles, varying between the International Standard, and that which is American. Waltz: The waltz is danced to melodic, slow music and is an equally beautiful dance form. The waltz is a graceful form of dance, that requires fluidity and delicate movement. When danced by the International Standard norms, this dance is performed more closely towards each other as compared to the American Style. Foxtrot: Foxtrot, as a dance style, gives a dancer flexibility to combine slow and fast dance steps together. -

The Rich Heritage of Dhrupad Sangeet in Pushtimarg On

Copyright © 2006 www.vallabhkankroli.org - All Rights Reserved by Shree Vakpati Foundation - Baroda ||Shree DwaDwarrrrkeshokesho Jayati|| || Shree Vallabhadhish Vijayate || The Rich Heritage Of Dhrupad Sangeet in Pushtimarg on www.vallabhkankroli.org Reference : 8th Year Text Book of Pushtimargiya Patrachaar by Shree Vakpati Foundation - Baroda Inspiration: PPG 108 Shree Vrajeshkumar Maharajshri - Kankroli PPG 108 Shree Vagishkumar Bawashri - Kankroli Copyright © 2006 www.vallabhkankroli.org - All Rights Reserved by Shree Vakpati Foundation - Baroda Contents Meaning of Sangeet ........................................................................................................................... 4 Naad, Shruti and Swar ....................................................................................................................... 4 Definition of Raga.............................................................................................................................. 5 Rules for Defining Ragas................................................................................................................... 6 The Defining Elements in the Raga................................................................................................... 7 Vadi, Samvadi, Anuvadi, Vivadi [ Sonant, Consonant, Assonant, Dissonant] ................................ 8 Aroha, avaroha [Ascending, Descending] ......................................................................................... 8 Twelve Swaras of the Octave ........................................................................................................... -

Baint an Fheir (Haymaker 'S Jig) (Ireland)

FOLK DANCE FEDERATION OF CALIFORNIA RESEARCH COMMITTEE December, 1961 Vera Jones and Wilma Andersen BAINT AN FHEIR (HAYMAKER 'S JIG) (IRELAND) Baint An Fheir (Bwint Un Air), which is best done with 5 couples, was taught by Una and Sean O'Farrell, at Uni versity of the Pacific Folk Dance Camp, Stockton, Cal'ifomia. MUSIC: Record: "Come To The Ceili", Top Rank Records of America, "Jigs", Side 2, Band 5. Also "My Ireland", Capitol T 10028, Side 2, Band 1, or any good jig. FORMATION: Longways formation of .5 cpls. M stand in one line, with hands joined, facing their ptrs who are in a similar line. M L shoulder is twd music. STEPS AND Basic Three's (Promenade) for jig: hop L (ct 6), step on R (ct 1,2), step on L (ct 3), step on R STYLING: (ct 4, 5). Next step would start with hop on R and use opp ft. This step may be done in place, moving in any direction or turning either R or L. ct: 6 1, 2 3 4, ') 6/8 ./" .; .t- ..; hop step step step L R L R Jig Step : hop L, at the same time touching R toe on floor slightly in front of L (ct 1,2,3); hop on L again, raising R in front of L leg (ct 4,5); hop on L again, bringing R back (ct 6) to step R, L, R, L (ct 1,2,3,4, hold 5,6). ct: 1,2,3 4,5 6 1 2 3 4 6/8 ..I. -

Model Queastion Bank for C G JE

QUESTION PAPER FOR THE WRITTEN TEST FOR TIIE POST OF JUNIOR ENGINEER(IvIECHANICAL) ON COMPASSIONATE GROLJND DIVISION: KUR , Date of Exam : 20. 10.2020 Total marks : : 150 Marks There are 4 sections in the question paper : - SECTION-'I' is carrying 20 marks - SECTION-'ll' is carrying 20 marks SECTION-'lll' is carrying 20 marks SECTION -'lV' is carrying 90 marks Total t7 a Total Time : 02.00 hrs sEcTtoN _ I IGENERAI AWARENESS) (Questlon no. 01 to 20 Carry one mark each) Choose the correct answer from the given optlons: 1) World Environment Day is celebrated on _. mqq+fl crfads_q{ffarlrqrfl tl a) 5th June b) 6th July c) 7th August d) 8th september qs{f, fioa-arg fr)73l-JrF strfrdcr 2) 'Thimphu'is the Gpital of frT 6I {rfirrfr tt a) Meghalaya b) Bhutan c) Manipur d) Sikkim (r)tsrdq dDqc'a OaFrg{ Ofrfuq 3) 'Sabarimala' is located in which of the following state? ,rstrErilffifud ue| 4 g frs f Fra tz a) Tamilnadu b) Kerala c) Karnataka d) Telengana qaft-d-dE Oi-rfr Os-dl-.6 SDAiirrm 4l How many fundamental rights are mentioned in lndian constitution? firc&q tfqra d' fuili dft-fi 3rfusr fir rrds ft.qr erqr t, a) Five b) Six c) Seven d) Eight 9crE fie-a dr)sra dDsn6 Page 1 of 17 5) Total number of districts in Odisha is _. 3i&n$ ffi 6r Ea,iwr_-g; al L7 b) 2s c) 30 d) 33 6) Which of the following is no longer a planet in our solar system? FeafrE-a d t dt-fr €rf,qrt dt{ asa fr rrfafi.t: a) Mercury b) Mars c) Neptune d) pluto (r)gq Oaa-n OAE-qd Oqi) 7) 'Mona Lisa' painting was made by _. -

Odissi Dance

ORISSA REFERENCE ANNUAL - 2005 ODISSI DANCE Photo Courtesy : Introduction : KNM Foundation, BBSR Odissi dance got its recognition as a classical dance, after Bharat Natyam, Kathak & Kathakali in the year 1958, although it had a glorious past. The temple like Konark have kept alive this ancient forms of dance in the stone-carved damsels with their unique lusture, posture and gesture. In the temple of Lord Jagannath it is the devadasis, who were performing this dance regularly before Lord Jagannath, the Lord of the Universe. After the introduction of the Gita Govinda, the love theme of Lordess Radha and Lord Krishna, the devadasis performed abhinaya with different Bhavas & Rasas. The Gotipua system of dance was performed by young boys dressed as girls. During the period of Ray Ramananda, the Governor of Raj Mahendri the Gotipua style was kept alive and attained popularity. The different items of the Odissi dance style are Mangalacharan, Batu Nrutya or Sthayi Nrutya, Pallavi, Abhinaya & Mokhya. Starting from Mangalacharan, it ends in Mokhya. The songs are based upon the writings of poets who adored Lordess Radha and Krishna, as their ISTHADEVA & DEVIS, above all KRUSHNA LILA or ŎRASALILAŏ are Banamali, Upendra Bhanja, Kabi Surya Baladev Rath, Gopal Krishna, Jayadev & Vidagdha Kavi Abhimanyu Samant Singhar. ODISSI DANCE RECOGNISED AS ONE OF THE CLASSICAL DANCE FORM Press Comments :±08-04-58 STATESMAN őIt was fit occasion for Mrs. Indrani Rehman to dance on the very day on which the Sangeet Natak Akademy officially recognised Orissi dancing -

List of Ccrt Scholarship Holders for the Year 2015-2016

LIST OF CCRT SCHOLARSHIP HOLDERS FOR THE YEAR 2015-2016 NAME OF SCHOLAR AUTHORISED PARENT S.NO. FILE NO. FIELD OF TRAINING HOLDER NAME/GUARDIAN NAME 1. SCHO/2015-16/00001 TRISHA BHATTACHARJEE TARUN BHATTACHARJEE FOLK SONGS HINDUSTANI MUSIC 2. SCHO/2015-16/00003 ALIK CHAUDHURI TANMAY CHAUDHURI VOCAL HINDUSTANI MUSIC 3. SCHO/2015-16/00004 DEBJANI NANDI CHANDAN NANDI VOCAL HINDUSTANI MUSIC 4. SCHO/2015-16/00005 SATTWIK CHAKRABORTY SUPRIYO CHAKRABORTY VOCAL HINDUSTANI MUSIC 5. SCHO/2015-16/00006 SANTANU SAHA GAUTAM SAHA VOCAL 6. SCHO/2015-16/00008 SUPTAKALI CHAUDHURI PREMANKUR CHAUDHORI RABINDRA SANGEET 7. SCHO/2015-16/00009 SUBHAYO DAS KAJAL KUMAR DAS RABINDRA SANGEET 8. SCHO/2015-16/00010 ANUVA ROY ASHIS ROY NAZRUL GEETI 9. SCHO/2015-16/00011 PLABAN NAG PRADIP NAG NAZRUL GEETI 10. SCHO/2015-16/00012 SURAJIT DEB KRISHNA BANDHU DEB GHAZAL HINDUSTANI MUSIC 11. SCHO/2015-16/00014 BARSHA DAS BANKIM CHANDRA DAS INSTRUMENT-GUITAR HINDUSTANI MUSIC 12. SCHO/2015-16/00016 ABHIGNAN SAHA GOPESH CHANDRA SAHA INSTRUMENT-TABLA 13. SCHO/2015-16/00017 DEBOLINA DEBNATH DWIJOTTAM DEBNATH HINDUSTANI MUSIC INSTRUMENT-VIOLIN 14. SCHO/2015-16/00020 BINDIYA SINGHA RAMENDRA SINGHA MANIPURI DANCE 15. SCHO/2015-16/00022 BARNITA CHOUDHURY NILADRI CHOUDHURY KATHAK 16. SCHO/2015-16/00023 ADWITIYA DEB ROY ASHISH DEBROY KATHAK 17. SCHO/2015-16/00024 SOUMYADEEP DEB SUSANTA CH. DEB KATHAK 18. SCHO/2015-16/00025 NUPUR SINHA PRADIP SINHA MANIPURI DANCE 19. SCHO/2015-16/00026 MONALISHA SINGHA BISWAJIT SINGHA MANIPURI DANCE 20. SCHO/2015-16/00027 RISHA CHOWDHURY RANA CHOWDHOURY BHARATNATAYAM 21. SCHO/2015-16/00028 NAYAN SAHA NANTURANJAN SAHA PAINTING 22. -

Newsletter 3/2014

Newsletter 3/2014 Liebe Freunde des Hauses, morgen beginnt unser Gamefest am Computerspielemuseum Die Vorbereitungen für das „Gamefest am Computerspielemuseum“ sind fast alle abgeschlossen. Wir freuen uns schon morgen den Höhepunkt des Frühjahrs zu eröffnen. Im Rahmen der INTERNATIONAL GAMES WEEK laden wir morgen ab 16.45 Uhr zur Vernissage der Ausstellung“Let´s Play! Computerspiele aus Frankreich und Polen“ ein. Vom 8. bis 13. April 2014 findet die INTERNATIONAL GAMES WEEK BERLIN statt. Sie tritt in die Fußstapfen der vom Medienboard Berlin-Brandenburg vor sieben Jahren initiierten Deutschen Gamestage und verfolgt mit einer neuen Organisationsstruktur die Ziele, internationaler zu werden und die Publikumsevents stärker zu betonen. Fester Bestandteil ist seit 2013 das vom Computerspielemuseum in Kooperation mit der Stiftung Digitale Spielekultur veranstaltete Gamefest am Computerspielemuseum. Es ist DAS Event für Gamer, Familien, Retro-Fans und Kultur-Interessierte. Die Rolle des Festes im Rahmen der GAMES WEEK ist es, einem breiten Publikum die Vielseitigkeit digitaler und interaktiver Unterhaltungskultur näher zu bringen. Das Programm des Gamefestes Dienstag, 8. April Vernissage der Ausstellung „Let´s Play! Computerspiele aus Frankreich und Polen“ Dauer: 16:45 – 18:00 Uhr Mit der Vernissage startet die Ausstellung „Let's Play! Computerspiele aus Frankreich und Polen“ im Computerspielemuseum. Grußworte werden Katarzyna Wielga-Skolimowska (Direktorin des Polnischen Instituts Berlin), der Direktor des Institut français d´Allemagne Emmanuel Suard und Dr Peter Beckers (Stellvertretender Bürgermeister von Friedrichshain-Kreuzberg, Stadtrat für Wirtschaft, Ordnung, Schule und Sport) sprechen. Danach schließt sich ein Rundgang durch die Ausstellung mit dem Kurator Andreas Lange an. Die Vernissage ist für alle Interessierten offen. Einlass ist ab 16 Uhr. -

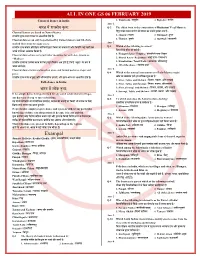

All in One Gs 06 फेब्रुअरी 2019

ALL IN ONE GS 06 FEBRUARY 2019 Classical Dance in India: 3. Yajurveda / यजुर्ेद 4. Rigveda / ऋग्र्ेद Ans- 2 भारत मᴂ शास्त्रीय न配ृ य: Q-2 The oldest form of the composition of Hindustani Vocal Music is: Classical Dances are based on Natya Shastra. सहंदुस्तानी गायन संगीत की रचना का सबसे पुराना 셂प है: शास्त्रीय नृ配य नाट्य शास्त्र पर आधाररत होते हℂ। 1. Ghazal / ग़ज़ल 2. Dhrupad / ध्रुपद Classical dances can only be performed by trained dancers and who have 3. Thumri / ठुमरी 4. Qawwali / कव्र्ाली studied their form for many years. Ans- 2 शास्त्रीय नृ配य के वल प्रशशशित नततशकयⴂ द्वारा शकया जा सकता है और शजन्हⴂने कई वर्षⴂ तक Q-3 Which of the following is correct? अपने 셁पⴂ का अध्ययन शकया है। सन륍न में से कौन सा सही है? Classical dances have very particular meanings for each step, known as 1. Hojagiri dance- Tripura / होजासगरी नृ配य- सिपुरा "Mudras". 2. Bhavai dance- Rajasthan / भर्ई नृ配य- राजस्थान शास्त्रीय नृ配यⴂ के प्र配येक चरण के शलए बहुत शवशेर्ष अर्त होते हℂ, शजन्हᴂ "मुद्रा" के 셂प मᴂ 3. Karakattam- Tamil Nadu / करकटम- तसमलनाडु जाना जाता है। 4. All of the above / उपरोक्त सभी Classical dance forms are based on grace and formal gestures, steps, and Ans- 4 poses. Q-4 Which of the musical instruments is of Indo-Islamic origin? शास्त्रीय नृ配य 셂पⴂ अनुग्रह और औपचाररक इशारⴂ, और हाव-भाव पर आधाररत होते हℂ। कौन सा र्ाद्ययंि इडं ो-इस्लासमक मूल का है? 1.