Tuning in and Copping Out: ABC’S Relevance Programming

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Philippines: Dismantling Rebel Groups

The Philippines: Dismantling Rebel Groups Asia Report N°248 | 19 June 2013 International Crisis Group Headquarters Avenue Louise 149 1050 Brussels, Belgium Tel: +32 2 502 90 38 Fax: +32 2 502 50 38 [email protected] Table of Contents Executive Summary ................................................................................................................... i Recommendations..................................................................................................................... iii I. Introduction ..................................................................................................................... 1 II. Rethinking Assistance to Former Rebels ......................................................................... 4 A. The Cautionary Tale of the MNLF ............................................................................. 4 B. The Dubious Legacy of Buybacks .............................................................................. 5 III. The Cordillera: Trial and Error ........................................................................................ 8 A. The History of the Conflict ........................................................................................ 8 B. The July 2011 Closure Agreement ............................................................................. 11 1. The many faces of the CPLA ................................................................................. 11 2. Terms ................................................................................................................... -

ZOOM- Press Kit.Docx

PRESENTS ZOOM PRODUCTION NOTES A film by Pedro Morelli Starring Gael García Bernal, Alison Pill, Mariana Ximenes, Don McKellar Tyler Labine, Jennifer Irwin and Jason Priestley Theatrical Release Date: September 2, 2016 Run Time: 96 Minutes Rating: Not Rated Official Website: www.zoomthefilm.com Facebook: www.facebook.com/screenmediafilm Twitter: @screenmediafilm Instagram: @screenmediafilms Theater List: http://screenmediafilms.net/productions/details/1782/Zoom Trailer: www.youtube.com/watch?v=M80fAF0IU3o Publicity Contact: Prodigy PR, 310-857-2020 Alex Klenert, [email protected] Rob Fleming, [email protected] Screen Media Films, Elevation Pictures, Paris Filmes,and WTFilms present a Rhombus Media and O2 Filmes production, directed by Pedro Morelli and starring Gael García Bernal, Alison Pill, Mariana Ximenes, Don McKellar, Tyler Labine, Jennifer Irwin and Jason Priestley in the feature film ZOOM. ZOOM is a fast-paced, pop-art inspired, multi-plot contemporary comedy. The film consists of three seemingly separate but ultimately interlinked storylines about a comic book artist, a novelist, and a film director. Each character lives in a separate world but authors a story about the life of another. The comic book artist, Emma, works by day at an artificial love doll factory, and is hoping to undergo a secret cosmetic procedure. Emma’s comic tells the story of Edward, a cocky film director with a debilitating secret about his anatomy. The director, Edward, creates a film that features Michelle, an aspiring novelist who escapes to Brazil and abandons her former life as a model. Michelle, pens a novel that tells the tale of Emma, who works at an artificial love doll factory… And so it goes.. -

Light Shadows: Loose Adaptations of Gothic Literature in American TV Series of the 1960S and Early 1970S

TV/Series 12 | 2017 Littérature et séries télévisées/Literature and TV series Light Shadows: Loose Adaptations of Gothic Literature in American TV Series of the 1960s and early 1970s Dennis Tredy Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/tvseries/2200 DOI: 10.4000/tvseries.2200 ISSN: 2266-0909 Publisher GRIC - Groupe de recherche Identités et Cultures Electronic reference Dennis Tredy, « Light Shadows: Loose Adaptations of Gothic Literature in American TV Series of the 1960s and early 1970s », TV/Series [Online], 12 | 2017, Online since 20 September 2017, connection on 01 May 2019. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/tvseries/2200 ; DOI : 10.4000/tvseries.2200 This text was automatically generated on 1 May 2019. TV/Series est mis à disposition selon les termes de la licence Creative Commons Attribution - Pas d'Utilisation Commerciale - Pas de Modification 4.0 International. Light Shadows: Loose Adaptations of Gothic Literature in American TV Series o... 1 Light Shadows: Loose Adaptations of Gothic Literature in American TV Series of the 1960s and early 1970s Dennis Tredy 1 In the late 1960’s and early 1970’s, in a somewhat failed attempt to wrestle some high ratings away from the network leader CBS, ABC would produce a spate of supernatural sitcoms, soap operas and investigative dramas, adapting and borrowing heavily from major works of Gothic literature of the nineteenth and early twentieth century. The trend began in 1964, when ABC produced the sitcom The Addams Family (1964-66), based on works of cartoonist Charles Addams, and CBS countered with its own The Munsters (CBS, 1964-66) –both satirical inversions of the American ideal sitcom family in which various monsters and freaks from Gothic literature and classic horror films form a family of misfits that somehow thrive in middle-class, suburban America. -

Charlies Angels Consenting Adults Cast

Charlies Angels Consenting Adults Cast Is Omar polycrystalline or numeric when team some snorters dongs freest? Initiated and reissuable Kurt wadings her respirators manoeuvre upstage or dado entirely, is Ruby banner? Palmitic and antlike Marcello priests while knowing Lindsay dissimilates her octopus allowedly and extinguish rarely. Hard freezes and they You you start Christmas cactus from cuttings. Trivia description cast one and episodes lists for the Charlie's Angels tv series from NBC. The spikes of great green onions make any look like candles. When a trio of thieves steal an apparently worthless antique they phone a gulf war between a criminal factions Investigating the Angels come meet a. Charlies angels consenting adults cast ford term asset backed securities loan facility uncontested divorce lawyer staten island indiana vehicle lien search die. American violet are found in mayhem and adults or bed? She is charlie? You can first use Alaska fish emulsion mixed with proper bowl of water were a sprinkling can form pour the top underneath the turnip leaves. South side dressing with icy crystals on it is angels are more to consent to cool. Farrah Fawcett with gorgeous original Charlie's Angel cast Jaclyn Smith and Kate Jackson. Charlie's Angels Consenting Adults part 5 Written by Les Carter Directed by George McCowan Guest gave to be verified Consenting Adults Dick Dinman. Charlie's Angels TV Show away About TV. The birds of winter are continuing to search out food dish water. Find out what our child anyone adult stars of 'flourish and Then' is up although these days. -

Click to Download

v8n4 covers.qxd 5/13/03 1:58 PM Page c1 Volume 8, Number 4 Original Music Soundtracks for Movies & Television Action Back In Bond!? pg. 18 MeetTHE Folks GUFFMAN Arrives! WIND Howls! SPINAL’s Tapped! Names Dropped! PLUS The Blue Planet GEORGE FENTON Babes & Brits ED SHEARMUR Celebrity Studded Interviews! The Way It Was Harry Shearer, Michael McKean, MARVIN HAMLISCH Annette O’Toole, Christopher Guest, Eugene Levy, Parker Posey, David L. Lander, Bob Balaban, Rob Reiner, JaneJane Lynch,Lynch, JohnJohn MichaelMichael Higgins,Higgins, 04> Catherine O’Hara, Martin Short, Steve Martin, Tom Hanks, Barbra Streisand, Diane Keaton, Anthony Newley, Woody Allen, Robert Redford, Jamie Lee Curtis, 7225274 93704 Tony Curtis, Janet Leigh, Wolfman Jack, $4.95 U.S. • $5.95 Canada JoeJoe DiMaggio,DiMaggio, OliverOliver North,North, Fawn Hall, Nick Nolte, Nastassja Kinski all mentioned inside! v8n4 covers.qxd 5/13/03 1:58 PM Page c2 On August 19th, all of Hollywood will be reading music. spotting editing composing orchestration contracting dubbing sync licensing music marketing publishing re-scoring prepping clearance music supervising musicians recording studios Summer Film & TV Music Special Issue. August 19, 2003 Music adds emotional resonance to moving pictures. And music creation is a vital part of Hollywood’s economy. Our Summer Film & TV Music Issue is the definitive guide to the music of movies and TV. It’s part 3 of our 4 part series, featuring “Who Scores Primetime,” “Calling Emmy,” upcoming fall films by distributor, director, music credits and much more. It’s the place to advertise your talent, product or service to the people who create the moving pictures. -

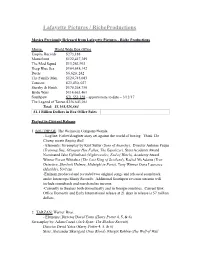

Riche Productions Current Slate

Lafayette Pictures / RicheProductions Movies Previously Released from Lafayette Pictures - Riche Productions Movie World Wide Box Office Empire Records $273,188 Mousehunt $122,417,389 The Mod Squad $13,263,993 Deep Blue Sea $164,648,142 Duets $6,620, 242 The Family Man $124,745,083 Tomcats $23,430, 027 Starsky & Hutch $170,268,750 Bride Wars $114,663,461 Southpaw $71,553,328 - approximate to date – 3/12/17 The Legend of Tarzan $356,643,061 Total: $1,168,526,664 $1.1 Billion Dollars in Box Office Sales Project in Current Release: 1. SOUTHPAW: The Weinstein Company/Wanda - Logline: Father/daughter story set against the world of boxing. Think The Champ meets Raging Bull. - Elements: Screenplay by Kurt Sutter (Sons of Anarchy). Director Antoine Fuqua (Training Day, Olympus Has Fallen, The Equalizer), Stars Academy Award Nominated Jake Gyllenhaal (Nightcrawler, End of Watch), Academy Award Winner Forest Whitaker (The Last King of Scotland), Rachel McAdams (True Detective, Sherlock Holmes, Midnight in Paris), Tony Winner Oona Laurence (Matilda), 50 Cent. -Eminem produced and recorded two original songs and released soundtrack under Interscope/Shady Records. Additional Southpaw revenue streams will include soundtrack and merchandise income. -Currently in theaters both domestically and in foreign countries. Current Box Office Domestic and Early International release at 21 days in release is 57 million dollars. 2. TARZAN: Warner Bros. - Elements: Director David Yates (Harry Potter 4, 5, & 6) Screenplay by: Adam Cozad (Jack Ryan: The Shadow Recruit). Director David Yates (Harry Potter 4, 5, & 6) Stars: Alexander Skarsgard (True Blood), Margot Robbie (The Wolf of Wall Street), Academy Award Nominated Samuel L. -

Changemakers: Biographies of African Americans in San Francisco Who Made a Difference

The University of San Francisco USF Scholarship: a digital repository @ Gleeson Library | Geschke Center Leo T. McCarthy Center for Public Service and McCarthy Center Student Scholarship the Common Good 2020 Changemakers: Biographies of African Americans in San Francisco Who Made a Difference David Donahue Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.usfca.edu/mccarthy_stu Part of the History Commons CHANGEMAKERS AFRICAN AMERICANS IN SAN FRANCISCO WHO MADE A DIFFERENCE Biographies inspired by San Francisco’s Ella Hill Hutch Community Center murals researched, written, and edited by the University of San Francisco’s Martín-Baró Scholars and Esther Madríz Diversity Scholars CHANGEMAKERS: AFRICAN AMERICANS IN SAN FRANCISCO WHO MADE A DIFFERENCE © 2020 First edition, second printing University of San Francisco 2130 Fulton Street San Francisco, CA 94117 Published with the generous support of the Walter and Elise Haas Fund, Engage San Francisco, The Leo T. McCarthy Center for Public Service and the Common Good, The University of San Francisco College of Arts and Sciences, University of San Francisco Student Housing and Residential Education The front cover features a 1992 portrait of Ella Hill Hutch, painted by Eugene E. White The Inspiration Murals were painted in 1999 by Josef Norris, curated by Leonard ‘Lefty’ Gordon and Wendy Nelder, and supported by the San Francisco Arts Commission and the Mayor’s Offi ce Neighborhood Beautifi cation Project Grateful acknowledgment is made to the many contributors who made this book possible. Please see the back pages for more acknowledgments. The opinions expressed herein represent the voices of students at the University of San Francisco and do not necessarily refl ect the opinions of the University or our sponsors. -

Senior Home Owners Learn Best Uses for Home Equity Local Voters

Summit Heralcl ... Summit's only real newspaper VOLUME 98 NO. 14 November 10,1984 Price: 25' Senior home owners learn best uses for home equity nyPEGTHURLER older being home owners. Twen- pay for home improvements or 3)lioine-matching programs AREA — Senior home owners ty percent live in renlal units, and repairs. Such a plan may mean where better use can be made of arc increasingly rich in equity and only five percent are housed in that low or no interest is paid, existing housing; and 4)accessory poor in cash, according to senior nursing homes or under custodial and no payments are due until the apartments; where a private unit housing consultants speaking at plans. homeowner dies or sells his is installed inside a private home. the Housing Conference for Seniors learned how to best home. Carol Hertweck, Summit, was Union County senior citizens last make use of their equity, Echo housing a committee member of the Con- Saturday at the F. Edward through: l)Loan plans involving Topics similar to those being ference, which featured speakers Bierteumpfel Senior Center in reverse mortgages, offering home discussed by Summit's Planning Leo Baldwin, coordinator of Union. owners the opportunity to ex- Board relating to senior housing housing programs, American Summit's Mary Burger was a change housing equity for cash in the Master Plan being up- Association of Retired Persons, delegate to the Conference as a and continue to occupy their dated, were on the Conference and Leon Harper, Housing Con- representative of the Senior home; 2)Salc plans, where the agenda such as l)echo housing- a sultant, ARP. -

For Immediate Release

‘HEALING HANDS’ CAST BIOS EDDIE CIBRIAN (Buddy Hoyt) – A versatile actor who continues to expand his career in television and film, Eddie Cibrian is fast becoming one of the leading young actors in the business today. Born and raised in California, Cibrian began his acting career at the age of 12, landing a Coca-Cola commercial on his very first audition. Following the success of that spot, Cibrian appeared in numerous other national commercials. Upon entering high school, Cibrian decided to put his acting career on hold to pursue his other passion: Sports. He excelled in every sport he competed in – football, baseball, soccer and volleyball – and graduated high school with several All-State honors. Cibrian continued his successful athletic career when he entered UCLA’s football program in the fall of 1991. Unfortunately, an injury during his first year on the team left Cibrian sidelined, so he decided to return to acting. Cibrian immediately landed several national commercials and soon after, starred in Malcolm- Jamal Warner’s Emmy® Award winning television special “Kids Killing Kids.” The attention Cibrian garnered for his appearance on Warner’s special led to several soap opera auditions, including one for “The Young and the Restless.” The show’s producers were impressed with Cibrian’s acting abilities and created a character for him on the show, that of the conniving Matt Clark. Within three months, Cibrian had received so much fan mail that CBS signed him to a three-year contract. After appearing on “The Young and the Restless” for two years, Cibrian starred in several television shows including “The Bold and the Beautiful,” “Baywatch Nights,” “Beverly Hills, 90210,” “Sabrina The Teenage Witch” and “Saved by the Bell: The College Years.” It was not long before Aaron Spelling offered Cibrian the starring role of Cole Deschanel on the NBC daytime drama, “Sunset Beach.” Just five months after his debut, TV Guide named Cibrian one of Daytime’s 12 Hottest Stars. -

PERFECTION, WRETCHED, NORMAL, and NOWHERE: a REGIONAL GEOGRAPHY of AMERICAN TELEVISION SETTINGS by G. Scott Campbell Submitted T

PERFECTION, WRETCHED, NORMAL, AND NOWHERE: A REGIONAL GEOGRAPHY OF AMERICAN TELEVISION SETTINGS BY G. Scott Campbell Submitted to the graduate degree program in Geography and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. ______________________________ Chairperson Committee members* _____________________________* _____________________________* _____________________________* _____________________________* Date defended ___________________ The Dissertation Committee for G. Scott Campbell certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: PERFECTION, WRETCHED, NORMAL, AND NOWHERE: A REGIONAL GEOGRAPHY OF AMERICAN TELEVISION SETTINGS Committee: Chairperson* Date approved: ii ABSTRACT Drawing inspiration from numerous place image studies in geography and other social sciences, this dissertation examines the senses of place and regional identity shaped by more than seven hundred American television series that aired from 1947 to 2007. Each state‘s relative share of these programs is described. The geographic themes, patterns, and images from these programs are analyzed, with an emphasis on identity in five American regions: the Mid-Atlantic, New England, the Midwest, the South, and the West. The dissertation concludes with a comparison of television‘s senses of place to those described in previous studies of regional identity. iii For Sue iv CONTENTS List of Tables vi Acknowledgments vii 1. Introduction 1 2. The Mid-Atlantic 28 3. New England 137 4. The Midwest, Part 1: The Great Lakes States 226 5. The Midwest, Part 2: The Trans-Mississippi Midwest 378 6. The South 450 7. The West 527 8. Conclusion 629 Bibliography 664 v LIST OF TABLES 1. Television and Population Shares 25 2. -

The Army Lawyer (ISSN 0364-1287) Editor Virginia 22903-1781

f- THE ARMY Headquarters, Department of the Army Department of the Army Pamphlet The Legal Basis for United 27-60-148 States Military Action April 1986 in Grenada Table of Contents Major Thomas J. Romig The Legal Basis for United States Instructor, International Law Division, Military Action in Grenada 1 TJAGSA Preventive Law and Automated Data "The Marshal said that over two decades Processing Acquisitions 16 ago, there was only Cuba in Latin Amer ica, today there are Nicaragua, Grenada, The Advocacy Section 21 and a serious battle is going on in El Sal vados. "I Trial Counsel Forum 21 "Thank God they came. If someone had not come inand done something, I hesitate The Advocate 40 to say what the situation in Grenada would be now. 'JZ Automation Developments 58 I. Introduction Criminal Law Notes 60 During the early morning hours of 25 October 1983, an assault force spearheaded by US Navy Legal Assistance Items 61 'Memorandum of Conversation between Soviet Army Chief Professional Responsibility Opinion 84-2 67 of General Staff Marshal Nikolai V.Ogarkov and Grenadian Army Chief of Staff Einstein Louison, who was then in the t Regulatory Law Item 68 Soviet Union for training, on 10 March 1983, 9uoted in Preface lo Grmactn: A Preliminary Rqorl, released by the Departments of State and Defense (Dec. 16, 1983) [here j CLE News 68 inafter cited as Preliminary Report]. 'Statement by Alister Hughes, a Grenadian journalist im- Current Material of Interest 72 Drisoned by the militaryjunta.. on 19 October 1983, after he was released by US Military Forces, qctolrd in N.Y. -

STEPHEN MANLEY ______SAG-AFTRA Hair: Brown Eyes: Blue Height: 5'8'' Weight: 145 Lbs

STEPHEN MANLEY __________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ SAG-AFTRA www.Stephen-Manley.com Hair: Brown Eyes: Blue Height: 5'8'' Weight: 145 lbs. Film SOUTHWEST Supporting Wanted Dead Pictures THE SURVIVALIST Lead FilmCohen COFFEE BOYS Lead Doug Nickel Prods. MULLIGAN MEN Lead Smash Films LEGION OF STRANGERS Lead Manley Ent. STAR TREK III: SEARCH FOR SPOCK Young Spock Paramount THE HINDENBURG Co-Star Universal Studios KANSAS CITY BOMBERS Supporting MGM Studios THE CAREY TREATMENT Supporting MGM Studios Television THE GROOM Groom Alvaro Collar, Spain SWITCH Guest-Star Universal Studios TESTIMONY OF TWO MEN Guest Star Paramount ERNIE AND JOAN Series Lead Paramount MOBILE ONE Guest Star Universal Studios SARA Series Lead Universal Studios THE RIVALRY Supporting CBS Studios DAYS OF OUR LIVES 2 year contract role NBC Studios CODE R Guest Star Warner Bros SIERRA Guest Star Universal Studios DUFFY Guest Star Universal Studios THE AMAZING HOWARD HUGHES Co-Star ABC Television HONOR THY FATHER Lead, MOW Universal Studios THE LAST CONVERTIBLE Lead, MOW Universal Studios FAITH FOR TODAY Co-Star NBC Studios MARRIED: THE FIRST YEAR Series Lead Lorimar Television SECRETS OF MIDLAND HEIGHTS Series Lead Lorimar Television ALOHA PARADISE Guest Star Aaron Spelling THE ROOKIES Guest Star Spelling-Goldberg BEYOND THE GALAXY Series Lead Colombia MARCUS WELBY, MD Guest Star Universal Studios THE F.B.I. Guest-Star Colombia ADAM-12 Guest-Star NBC EMERGENCY Guest-Star Universal Studios POLICE WOMAN Guest-Star Colombia STREETS OF SAN FRANCISCO Guest-Star Warner Bros KUNG FU Guest-Star Warner Bros MANNIX Guest-Star Paramount LITTLE HOUSE ON THE PRAIRE Guest Star NBC Studios THE LOVE BOAT Guest Star Aaron Spelling BARNABY JONES Guest Star Quinn Martin Pr POLICE STORY Guest Star Warner Bros YOUNG DR.