Comedy, Satire, Paradox, and the Plurality of Discourses in Cinquecento Italy: Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

On the Threshold of Poems: a Paratextual Approach to the Narrative/Lyric Opposition in Italian Renaissance Poetry

This is a repository copy of On the Threshold of Poems: a Paratextual Approach to the Narrative/Lyric Opposition in Italian Renaissance Poetry. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/119858/ Version: Accepted Version Book Section: Pich, F (2019) On the Threshold of Poems: a Paratextual Approach to the Narrative/Lyric Opposition in Italian Renaissance Poetry. In: Venturi, F, (ed.) Self-Commentary in Early Modern European Literature, 1400-1700. Intersections, 62 . Brill , pp. 99-134. ISBN 9789004346864 https://doi.org/10.1163/9789004396593_006 © Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, 2019. This is an author produced version of a paper published in Self-Commentary in Early Modern European Literature, 1400-1700 (Intersections). Uploaded in accordance with the publisher's self-archiving policy. Reuse Items deposited in White Rose Research Online are protected by copyright, with all rights reserved unless indicated otherwise. They may be downloaded and/or printed for private study, or other acts as permitted by national copyright laws. The publisher or other rights holders may allow further reproduction and re-use of the full text version. This is indicated by the licence information on the White Rose Research Online record for the item. Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ 1 On the Threshold of Poems: a Paratextual Approach to the Narrative/Lyric Opposition in Italian Renaissance Poetry Federica Pich Summary This contribution focuses on the presence and function of prose rubrics in fifteenth- and sixteenth-century lyric collections. -

Sheri F. Shaneyfelt Department of History of Art, Vanderbilt University PMB 0274, 230 Appleton Place, Nashville, TN 37203-5721 [email protected]

Sheri F. Shaneyfelt Department of History of Art, Vanderbilt University PMB 0274, 230 Appleton Place, Nashville, TN 37203-5721 [email protected] EDUCATION Ph. D., History of Art, Indiana University at Bloomington Dissertation: “The Perugian Painter Giannicola di Paolo: Documented and Secure Works” Advisors: Bruce Cole and Molly Faries Areas of concentration: Italian and Northern European art of the 14th-17th centuries M. A., History of Art, Vanderbilt University M.A. Thesis: “Fifteenth-Century Netherlandish Secular Images of Justice Commissioned for Town Halls” Areas of concentration: Netherlandish Painting, Early Christian/Byzantine Art B. S., Biology and History of Art, Centre College PROFESSIONAL EXPERIENCE Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tennessee; Senior Lecturer in History of Art, 2002-04; 2007-present Director of Undergraduate Studies, 2008-present Prior teaching appointments c/o: The Umbra Institute, Perugia, Italy The Institute for Fine and Liberal Arts at Palazzo Rucellai, Florence, Italy Indiana University, Bloomington COURSES TAUGHT Italian Renaissance Art and Architecture, 14th-16th centuries; Early Renaissance Florence Michelangelo Buonarroti: Life and Works; Raphael and the Renaissance Northern European Renaissance Art/Netherlandish Painting Seventeenth-Century Art and Architecture, Northern and Southern Europe History of Art Surveys I and II; Freshman Seminar: Art and Power SELECT PUBLICATIONS “The Società del 1496: Supply, Demand, and Artistic Exchange in Renaissance Perugia,” The Art Bulletin, 97, 1 (March 2015), pp. 10-33. “Giannicola di Paolo’s collaboration with Pietro Perugino at the Cenacolo di Foligno, Florence,” Zeitschrift für Kunstgeschichte, 73, 4 (2010), pp. 573-86. “A Reappraisal of Giannicola di Paolo’s Early Career,” The Burlington Magazine 149 (2007). “School of Pietro Perugino, St. -

The Mourning Saint John the Evangelist C

National Gallery of Art NATIONAL GALLERY OF ART ONLINE EDITIONS Italian Paintings of the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Centuries Master of the Franciscan Crucifixes Umbrian, active 1260s and 1270s The Mourning Saint John the Evangelist c. 1270/1275 tempera on panel original panel: 81.2 × 31.1 cm (31 15/16 × 12 1/4 in.) overall: 82.2 × 33.3 cm (32 3/8 × 13 1/8 in.) framed: 91.1 x 41.8 x 6 cm (35 7/8 x 16 7/16 x 2 3/8 in.) Samuel H. Kress Collection 1952.5.14 ENTRY Because of their relatively large size, this panel and its companion, The Mourning Madonna, have been considered part of the apron of a painted crucifix. [1] As their horizontal wood grain suggests, they undoubtedly formed the lateral terminals of a painting of this type, probably that belonging to the church of Santa Maria in Borgo in Bologna (now exhibited at the Pinacoteca Nazionale of that city), as Gertrude Coor was the first to recognize [fig. 1] (see also Reconstruction). [2] Another fragment of the work, a tondo with the bust of the Blessing Christ [fig. 2], was in the possession of the art dealer Bacri in Paris around 1939. [3] The two panels represent, respectively, the mother of Jesus and his favorite disciple in the typical pose of mourners, with the head bowed to one side and the cheek resting on the palm of the hand. [4] As is seen frequently in Italian paintings of the late thirteenth century, Mary is wearing a purple maphorion over a blue robe, [5] and Saint John a steel-blue garment and purple-red mantle. -

The History of Cartography, Volume 3

36 • Cartography in the Central Italian States from 1480 to 1680 Leonardo Rombai The purpose of this chapter is to document the consider- states and duchies of central Italy included the Papal able cartographic activity that took place in a two-century States (which after 1631 also included the Duchy of period in the central Italian states. These states were bor- Urbino), the Grand Duchy of Tuscany, the Republic dered to the north by the Republic of Genoa, the Duchy of Lucca, and other smaller political entities (the Repub- of Milan, and the Venetian Republic, and in the south lic of San Marino, the Principality of Piombino, and the by the Kingdom of Naples. The region of Emilia com- presidios under Spanish control, such as Orbetello, and prised the Duchies of Parma and Piacenza (under Farnese Talamone). rule since 1545) and Modena (which, under Este rule, The maps produced in these regions fall broadly into also controlled Ferrara until 1598) (fig. 36.1). Other three general categories based on their practical function: administering the social infrastructure of regions, borders, cities, and communication routes; recording and control- ling land ownership; and managing natural resources for Caselnuovo 10° 11° 12° 13° Campiglia Bocca d’Adda Cremona Mantua agriculture and industry. None of these categories is ex- Po 45° Piacenza clusive, and the functions of the maps and projects de- Sacca Mezzano Rondani o 45° Busseto e P A ron Sti Coenzo Brescello Ferrara scribed might fall into two categories or all three. This is o Parma l o Cento t A Reggio o s particularly true when discussing military uses of maps or r Ta o r Comacchio D L C u a Modena n i Reno h the rhetorical functions of scholarship, politics, and reli- i g a c R i z P c a e Sassuolo n n E S I Pontremoli a Bologna C gion that infuse these categories. -

Italian Renaissance Art Course ID: ARH 325 Semester: Summer I 2020 Mode: Online

Course Information Course Name: Italian Renaissance Art Course ID: ARH 325 Semester: Summer I 2020 Mode: Online Instructor Information Name: Karen Maria Abbondanza Email: [email protected] Phone: 401-835-4903 Office Hours: Online, by appointment only. Course Description A study of painting and sculpture from the 15th and 16th centuries in Italy. You may choose to work at your own pace, but I encourage you to complete each week in a timely manner as you will be overwhelmed if you fall behind. The Renaissance in Italy begins nearly one hundred years before anywhere else in Western Europe. Even within their own lifetimes, Giotto, Brunelleschi, Michelangelo and Leonardo understood that they were the makers of something completely new in the visual arts, that would both embody and inform their patrons, their physical environments, and the culture in general. Artists were employed by patrons to exert physical and spiritual authority, and the various types of artistic production-- frescoes, altarpieces, monumental sculptures-- as well as their respective spaces--civic buildings, churches, monasteries or private palaces-- is evidence of this. Not since Classical Greece had there been such a period of creative activity of the arts, and the number of brilliant innovators in the just the visual artistic arena is staggering. Course Credits: 3 Required Text: Kleiner - MindTap for Kleiner's Gardner's Art Through the Ages: A Global History, 1 term Printed Access Card ISBN: 9781337696869 Required Materials: You must purchase the Cengage MindTap access along with the textbook. Course Objectives • Develop the skills of visual analysis and interpretation • Place works of art in their social and cultural contexts • Develop the skills to discuss observations in academic writing Communication Plan Expectations for Electronic Communication Please use email *ONLY* when the subject is of a personal and confidential matter. -

Engaging with Engraving in Cinquecento Northern Italian Art

Drawing from Mantegna: Engaging with Engraving in Cinquecento Northern Italian Art Kylie Fisher Renaissance artists frequently derived inspiration from the The early sixteenth-century brown ink drawing rep- designs of other masters, and the emerging art form of resents a detailed portrayal of Saint Christopher with the engraving encouraged them to consider prints as tools for Christ Child. Following iconographic convention, the patron subsequent pictorial creations. One of the most influential saint of travelers is depicted standing ankle-deep in a pool Italian Renaissance printmakers was Andrea Mantegna. of water while carrying the infant Christ upon his shoulder. The impact of Mantegna’s engravings on artistic process He also grasps his standard attribute: a palm staff. In addition in Cinquecento Northern Italy is exemplified in an early to rendering the basic outlines and features of the figures, sixteenth-century drawing of Saint Christopher, which now drapery, and landscape, the draftsman included modeling resides in the Cleveland Museum of Art (Figure 1).1 By on the surfaces of Saint Christopher, Christ, and the palm examining the formal features of this object, it is clear that through a series of hatch marks. His use of hatching to portray the draftsman was intimately aware of Mantegna’s prints shading demonstrates a desire to give the figures a sense of because specific elements from one of the master’s late three-dimensionality. The level of refinement in the image fifteenth-century engravings also appear in the drawing.2 suggests that the drawing did not serve as a preliminary sketch While the draftsman’s choice to model his work after one for a future composition, but instead should be recognized of Mantegna’s designs is not unique to the Cleveland image, as a finished work of art that was intended for an audience what is noteworthy is his deliberate attempt to simulate the outside of the workshop. -

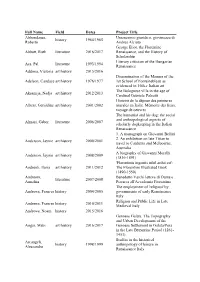

Full Name Field Dates Project Title Abbondanza, Roberto History 1964

Full Name Field Dates Project Title Abbondanza, Umanesimo giuridico, giovinezza di history 1964/1965 Roberto Andrea Alciato George Eliot, the Florentine Abbott, Ruth literature 2016/2017 Renaissance, and the History of Scholarship Literary criticism of the Hungarian Acs, Pal literature 1993/1994 Renaissance Addona, Victoria art history 2015/2016 Dissemination of the Manner of the Adelson, Candace art history 1976/1977 1st School of Fontainebleau as evidenced in 16th-c Italian art The Bolognese villa in the age of Aksamija, Nadja art history 2012/2013 Cardinal Gabriele Paleotti Histoire de la dépose des peintures Albers, Geraldine art history 2001/2002 murales en Italie. Mémoire des lieux, voyage de oeuvres The humanist and his dog: the social and anthropological aspects of Almasi, Gabor literature 2006/2007 scholarly dogkeeping in the Italian Renaissance 1. A monograph on Giovanni Bellini 2. An exhibition on late Titian to Anderson, Jaynie art history 2000/2001 travel to Canberra and Melbourne, Australia A biography of Giovanni Morelli Anderson, Jaynie art history 2008/2009 (1816-1891) 'Florentinis ingeniis nihil ardui est': Andreoli, Ilaria art history 2011/2012 The Florentine Illustrated Book (1490-1550) Andreoni, Benedetto Varchi lettore di Dante e literature 2007/2008 Annalisa Petrarca all'Accademia Fiorentina The employment of 'religiosi' by Andrews, Frances history 2004/2005 governments of early Renaissance Italy Religion and Public Life in Late Andrews, Frances history 2010/2011 Medieval Italy Andrews, Noam history 2015/2016 Genoese -

Carolyn's Guide to Florence and Its

1 Carolyn’s Guide to Be selective Florence and Its Art San Frediano Castello See some things well rather than undertaking the impossible task of capturing it all. It is helpful, even if seeming compulsive, to create a day planner (day and hour grid) and map of what you want to see. Opening hours and days for churches and museums vary, and “The real voyage of discovery consists not in it’s all too easy to miss something because of timing. seeking new landscapes but in having new eyes.” I make a special effort to see works by my fa- vorite artists including Piero della Francesca, Masac- Marcel Proust, Remembrance of Things Past cio, Titian, Raphael, Donatello, Filippo Lippi, Car- avaggio, and Ghirlandaio. I anticipate that it won’t be long before you start your own list. Carolyn G. Sargent February 2015, New York 2 For Tom, my partner on this voyage of discovery. With special thanks to Professoressa d’arte Rosanna Barbiellini-Amidei. Contents 1 Introduction 5 1.1 TheQuattrocento ............................................... 5 1.2 Reflections of Antiquity . 8 1.3 Perspective, A Tool Regained . 10 1.4 CreatorsoftheNewArt............................................ 10 1.5 IconographyandIcons............................................. 13 1.6 The Golden Legend ............................................... 13 1.7 Angels and Demons . 14 1.8 TheMedici ................................................... 15 2 Churches 17 2.1 Duomo (Santa Maria del Fiore) . 17 2.2 Orsanmichele . 21 2.3 Santa Maria Novella . 22 2.4 Ognissanti . 25 2.5 Santa Trinita . 26 2.6 San Lorenzo . 28 2.7 San Marco . 30 2.8 SantaCroce .................................................. 32 2.9 Santa Felicita . 35 2.10 San Miniato al Monte . -

The Seventeenth-Century Crisis Revisited. the Case of the Southern Italian Silk Industry: Reggio Calabria, 1547-1686

THE SEVENTEENTH-CENTURY CRISIS REVISITED. THE CASE OF THE SOUTHERN ITALIAN SILK INDUSTRY: REGGIO CALABRIA, 1547-1686 Antonio Calabria University of Texas, San Antonio ABSTRACT This essay examines the silk trade in Southern Italy through a quantitative study of exports from the dry-customs port of Reggio Calabria. It traces the experience of Reggio’s silk industry from its heyday in the sixteenth century to its collapse in the seventeenth, and it places that experience in the con text of the economic decline of Southern Italy and of the literature on the crisis of the seventeenth century It is a truism of European economic history that the seventeenth century brought great changes to many areas that, in the preceding three-hundred (or even six-hundred) years had been at the core of the European and the world economy. One need not be a historian of the economy of Europe to know, for example, that an epic shift in the locus of significant economic activity took place in the course of the 1 600s and that, as a consequence, after 1650 the core of the European economy was no longer Italy and the Mediterranean, but Northwestern Europe — the United Provinces and, increasingly, Great Britain. Especially in the 1960s and the 1970s, the details of those changes and of that shift stimulated an intense debate which became a classic of European historiography. That was, of course, the debate on “the crisis of the seventeenth century” best summa rized in a series of essays which appeared in Past and Present and which Trevor Aston collected and published as Crisis in Europe, 1560-1660.’ The breadth and the implications of the material attracted more than economic historians to the debate. -

An Agenda for the Study of Long-Enduring Institutions of Self-Governance in the Italian South

AN AGENDA FOR THE STUDY OF LONG-ENDURING INSTITUTIONS OF SELF-GOVERNANCE IN THE ITALIAN SOUTH by Filippo Sabetti McGill University [email protected] Paper prepared for the Panel "The New South: New Research on an Old Question," American Political Science Association Meetings, Atlanta Georgia September 2-5, 1999. AN AGENDA FOR THE STUDY OF LONG-ENDURING INSTITUTIONS OF SELF-GOVERNANGE IN THE ITALIAN SOUTH Filippo Sabetti Long before the creation of the Italian state in the nineteenth century, Italy was the scene of many other experiments in political, economic and ecclesiastical organizations. Such a rich heritage posed dilemmas during the Risorgimento about the meaning of the past and how to face the future. These dilemmas were perhaps no more evident than for the areas that had formed the Kingdom of Two Sicilies, as the subsequent literature on the so-called Southern Question attests. Unfortunately, the understanding of South Italian development that has come to us from this literature, and especially from Liberal, Crocean and Gramscian historiography, is deeply flawed, or is at least too partial and one-sided, to serve as reliable wisdom. There is more to the history of the South than the theme of failure, or the negative self-perceptions of some Southerners' own history. In fact, growing evidence from more recent empirical studies in history and social science has increasingly challenged the generalizability of the received wisdom about the South. To borrow from what Elinor Ostrom (1998) has said in another context, the consequence of these empirical studies is not to challenge the empirical validity of the received wisdom where it is relevant but rather its generalizability to the entire South across time and space. -

Population and Environment in Northern Italy During the 16Th Century

1 Guido Alfani Università L. Bocconi – Istituto di Storia Economica Via Castelbarco 2 20136 Milano – Italy E-Mail: [email protected] Fax +39 (0)2 58102284 – Mobile +39 333 2900066 Population and environment in Northern Italy during the 16th Century. (working paper) Guido Alfani Bocconi University 2 Abstract “Population and environment in Northern Italy during the 16th Century” No general consensus has been reached, as yet, on how to interpret 16th Century Italian demographic dynamics. Such divergences imply different convictions about the relationship between population and resources. On the base of 164 series of baptisms celebrated in Northern Italian parishes and adopting a comparative perspective, this paper progressively evaluates the demographic weight of environmental factors (placement in lowland, mountain or coastal areas; urban or rural environment; for rural areas, different settlement patterns and crop regimes), and permits us to get a better insight on the relationship between population and resources (Malthusian, “Boserupian”, or something else?). The paper reveals a complex situation, where environmental and socio-economic factors have an impact not only on the demographic trend but on the very logics of population, and where advancements in agrarian technology does not always play a demographically positive role. 3 Introduction Studies in historical demography based on time series have often given the impression that it is only possible to give an account of Italian population history starting from the middle of the 17 th century. However, if we take into account works based on sources other than those traditionally used by demographers, we come upon excellent studies on the Middle Ages characterised by particular methods. -

Famines in Late Medieval and Early Modern Italy: a Test for an Advanced Economy

Famines in late Medieval and Early Modern Italy: a test for an advanced economy Guido Alfani Bocconi University and Dondena Centre (Milan, Italy) [email protected] (preliminary and incomplete draft; please do not quote without author's authorization) In the late Middle Ages and at the beginning of the Early Modern period, Italy was without doubt one of the most advanced areas of Europe, both economically, socially, and regarding its institutions. Even if the old theory of a 'seventeenth century crisis' ( crisi del Seicento ) has been considerably mitigated by the research conducted in the last thirty years, from the seventeenth century Italy started losing positions in relation to the dynamic north European economies. The reasons of this 'relative decline', as well as its overall intensity, are still the object of heated discussions. Related to this, recent works provided an overall reappraisal of the Italian economic conditions during the sixteenth century (Alfani 2010a). Most Italian states have been shown to possess a considerable economic vitality also in the second half of the sixteenth century, when a large part of the peninsula had already lost its political independence. The recovery after the damages and the economic instability caused by the Italian Wars (1494-1559) was not an 'Indian summer', as Carlo M. Cipolla had it (1993, 243), but was a sound recovery that led Italy to reach, from many points of view, a multi-secular peak. However, it is towards the end of the century, in the 1590s, that Italy had to endure the worst famine of the late Medieval and Early Modern period.