'His Terrible Masterpiece'

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Peter Pan in Scarlet’ for Key Stage 2 Years 3-6, Ages 7-11

‘Peter Pan in Scarlet’ for Key stage 2 Years 3-6, ages 7-11 Using imagination Choose a character from Peter Pan in Scarlet and imagine the story (or part of the story) from their point of view. For example: • Peter Pan. Once Peter Pan has discovered Captain Hook’s second-best coat and decided to wear it, he morphs into a form of Captain Hook, growing long dark curls, inheriting his bad temper, and speaking like a pirate! The story centres around the idea that clothes maketh the man. Only when he removes the coat does he become himself again. Equally, when Ravello wears the coat, he is hardened and returns to the form of Captain Hook, and not the travelling, ravelling man. What is going through Peter’s mind as he morphs into Hook? • Ask your children to write letters from one of the characters to another, ie: Wendy Darling in Neverland, to her daughter Jane in London. • Tootles Darling: As an adult, Tootles is a portly judge who loves his moustache and believes everything can be solved judicially. Tootles only has daughters, so in order to return to Neverland like his fellow Old Boys, he must dress like a girl in his daughter’s clothes! This is fine with the female Tootles, who dreams of becoming a princess and a nurse, and marrying Peter, and become Tootles Pan! Imagine what it must be like for Tootles to suddenly become a girl! Ask your pupils to discuss this – both the girls and the boys. Creative and descriptive writing • Write a book review Ask your children to write a short book review on Peter Pan in Scarlet. -

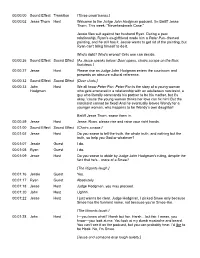

00:00:02 Jesse Thorn Host Welcome to the Judge John Hodgman Podcast

00:00:00 Sound Effect Transition [Three gavel bangs.] 00:00:02 Jesse Thorn Host Welcome to the Judge John Hodgman podcast. I'm Bailiff Jesse Thorn. This week: "Neverlandmark Case." Jessie files suit against her husband Ryan. During a past relationship, Ryan's ex-girlfriend made him a Peter Pan–themed painting, and he still has it. Jessie wants to get rid of the painting, but Ryan can't bring himself to do it. Who's right? Who's wrong? Only one can decide. 00:00:26 Sound Effect Sound Effect [As Jesse speaks below: Door opens, chairs scrape on the floor, footsteps.] 00:00:27 Jesse Host Please rise as Judge John Hodgman enters the courtroom and presents an obscure cultural reference. 00:00:32 Sound Effect Sound Effect [Door shuts.] 00:00:33 John Host We all know Peter Pan. Peter Pan is the story of a young woman Hodgman who gets ensnared in a relationship with an adulterous narcissist, a guy who literally commands his partner to be his mother, but it's okay, 'cause the young woman thinks her love can fix him! But the narcissist cannot be fixed! And he eventually leaves Wendy for a younger woman, who happens to be Wendy's own daughter! Bailiff Jesse Thorn, swear them in. 00:00:59 Jesse Host Jesse, Ryan, please rise and raise your right hands. 00:01:00 Sound Effect Sound Effect [Chairs scrape.] 00:01:02 Jesse Host Do you swear to tell the truth, the whole truth, and nothing but the truth, so help you God or whatever? 00:01:07 Jessie Guest I do. -

On Family Films

FAMILY FILMS ON TITLE GENRE RATING 101 DALMATIANS: SIGNATURE COLLECTION (2019) ADVENTURE/ANIMATION G ABOMINABLE (2019) ADVENTURE PG ALADDIN (2019) ADVENTURE/COMEDY PG ALEXANDER AND THE TERRIBLE, HORRIBLE,NO GOOD… (2014) COMEDY/FAMILY PG ALICE THROUGHT THE LOOKING GLASS (2016) ACTION/FAMILY/FANTASY PG ALPHA & OMEGA 2 (2013) FAMILY TV-G ALPHA & OMEGA: FAMILY VACATION (2014) FAMILY TV-G ALVIN AND THE CHIPMUNKS: THE ROAD CHIP (2015) COMEDY/FAMILY/MUSICAL PG AMERICAN TAIL (1986) FAMILY G ANGELS SING (2013) DRAMA/FAMILY PG ANGRY BIRDS MOVIE 2 (2019) ADVENTURE/ANIMATION/FAMILY PG ANNIE (2014) COMEDY/DRAMA/FAMILY PG ART OF RACING IN THE RAIN (2019) COMEDY/DRAMA PG ARTHUR CHRISTMAS (2011) COMEDY/FAMILY PG BARK RANGER (2014) ACTION/FAMILY/ADVENTURE PG BEAUTIFUL DAY IN THE NEIGHBORHOOD (2019) DRAMA PG BEAUTY AND THE BEAST (2017) FAMILY/MUSICAL/ROMANCE PG BIRDS OF PARADISE (2014) FAMILY PG BORN IN CHINA (2017) DOCUMENTARY G BOSS BABY (2017) COMEDY/FAMILY PG BUTTONS: A CHRISTMAS TALE (2019) FAMILY PG CALL OF THE WILD (2020) ADVENTURE/DRAMA PG CAPTAIN UNDERPANTS:THE FIRST EPIC MOVIE (2017) COMEDY/FAMILY/ADVENTURE PG CARS 3 (2017) COMEDY/FAMILY/ADVENTURE G CATS (2020) COMEDY/DRAMA PG CHRISTOPHER ROBIN (2018) COMEDY/FAMILY PG CLOUDY WITH A CHANCE…2 (2013) COMEDY/FAMILY PG COCO (2017) COMEDY/FAMILY PG CROODS: A NEW AGE (2020) ADVENTURE/ANIMATION PG DESPICABLE ME 2 (2013) FAMILY PG DESPICABLE ME 3 (2017) COMEDY/FAMILY/ADVENTURE PG DIARY OF A WIMPY KID: THE LONG HAUL (2017) COMEDY/FAMILY PG DOG'S JOURNEY (2019) COMEDY/DRAMA PG DOG'S PURPOSE (2017) COMEDY/DRAMA PG DOG'S WAY HOME (2019) DRAMA/ADVENTURE PG DOLITTLE (2020) ADVENTURE/COMEDY PG DORA AND THE CITY OF GOLD (2019) ADVENTURE/COMEDY PG DR. -

Convergence Culture: an Approach to Peter Pan, by JM Barrie Through

Departamento de Filoloxía Inglesa e Alemá FACULTADE DE FILOLOXÍA Convergence Culture: An approach to Peter Pan, by J. M. Barrie through “the fandom”. SHEILA MARÍA MAYO MANEIRO TRABALLO FIN DE GRAO GRAO EN LINGUA E LITERATURA INGLESAS LIÑA TEMÁTICA: Texto, Imaxe e Cibertexto FACULTADE DE FILOLOXÍA UNIVERSIDADE DE SANTIAGO DE COMPOSTELA CURSO 2017/ 2018 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................................ 2 2. GENERIC FEATURES ............................................................................................................. 5 2.1. Convergence Culture ................................................................................................................. 5 2.2. Importance of the fans as ‘prosumers’ ................................................................................. 8 3. PETER PAN AS A TRANSMEDIAL FIGURE .......................................................... 15 4. PETER PAN AS A FANFICTION ..................................................................................... 19 4.1. Every Pain has a Story .............................................................................................................. 19 4.2. The Missing Thimble ................................................................................................................ 24 4.3. Duels ............................................................................................................................................... -

A Check-List of All Animated Disney Movies

A CHECK-LIST OF ALL ANIMATED DISNEY MOVIES WALT DISNEY FEATURE ANIMATION WALT DISNEY PRODUCTIONS DISNEYTOON STUDIOS 157. Lady And The Tramp II: 1. 1 Snow White and the Seven 60. The Academy Award Review 108. Bambi II (2006) Scamp’s Adventure (2001) Dwarfs (1937) of Walt Disney Cartoons (1937) 109. Brother Bear 2 (2006) 158. Leroy And Stitch (2006) 2. 2 Pinocchio (1940) 61. Bedknobs and Broomsticks 110. Cinderella III: A Twist in 159. The Lion Guard: Return of 3. 3 Fantasia (1940) (1971) Time (2007) the Roar (2015) 4. 4 Dumbo (1041) 62. Mary Poppins (1964) 111. The Fox and the Hound 2 160. The Lion King II: Simba’s 5. 5 Bambi (1942) 63. Pete’s Dragon (1977) (2006) Pride (1998) 6. 6 Saludos Amigos (1943) 64. The Reluctant Dragon (1941) 112. The Jungle Book 2 (2003) 161. The Little Mermaid II: 7. 7 The Three Caballeros 65. So Dear To My Heart (1949) 113. Kronk’s New Groove (2005) Return to the Sea (2000) (1945) 66. Song of the South (1946) 114. Lilo and Stitch 2: Stitch Has 162. Mickey’s House of Villains 8. 8 Make Mine Music (1946) 67. Victory through Air Power A Glitch (2005) (2002) 9. 9 Fun and Fancy Free (1947) (1943) 115. The Lion King 1½ (2004) 163. Mickey’s Magical Christmas: 10. 10 Melody Time (1948) 116. The Little Mermaid: Ariel’s Snowed In at the House of 11. 11 The Adventures of WALT DISNEY PICTURES Beginning (2008) Mouse (2001) Ichabod and Mr. Toad (1949) ANIMATED & MOSTLY ANIMATED 117. -

Fairy Dust Free

FREE FAIRY DUST PDF Gwyneth Rees | 160 pages | 01 Aug 2016 | Pan MacMillan | 9781509818679 | English | London, United Kingdom Black Fairy Dust - The Official Terraria Wiki Tinker Bell is a fictional character from J. Barrie 's play Peter Pan and its novelization Peter and Wendy. She has appeared in a variety of film and television adaptations of the Peter Pan stories, in particular the animated Walt Disney picture Peter Pan. At first only a Fairy Dust character described by her creator as "a common fairy ", her animated incarnation was a hit and has since become a widely recognized unofficial mascot of The Walt Disney Companynext to the company's official mascot Mickey Mouseand the centrepiece of its Disney Fairies media franchise Fairy Dust the direct-to-DVD film series Tinker Bell and Walt Disney's Wonderful World of Fairy Dust. Barrie described Tinker Bell as a fairy who mended pots and kettles, an actual tinker of the fairy folk. Though sometimes ill-tempered, spoiled, jealous, vindictive and inquisitive, she is also helpful and kind to Peter. At the end of the novel, when Peter flies back to find an older Wendy, it is mentioned that Tinker Bell died Fairy Dust the year after Wendy and her brothers left Neverland, and Peter no longer remembers her. In the first version of the play, she is called Tippy-toe, but became Tinker Bell in the later drafts and final version. In the original stage productions, Tinker Bell was represented on stage by a darting light "created by a small mirror held in the hand off-stage and reflecting a little circle of light from a powerful lamp" [4] and her voice was "a collar of bells and two special ones that Barrie brought from Switzerland". -

25-1-S2016.Pdf

The ESSE Messenger A Publication of ESSE (The European Society for the Study of English Vol. 25-1 Summer 2016 ISSN 2518-3567 All material published in the ESSE Messenger is © Copyright of ESSE and of individual contributors, unless otherwise stated. Requests for permissions to reproduce such material should be addressed to the Editor. Editor: Dr. Adrian Radu Babes-Bolyai University, Cluj-Napoca, Romania Faculty of Letters Department of English Str. Horea nr. 31 400202 Cluj-Napoca Romania Email address: [email protected] Cover drawing: Mădălina Slova (10 years), Nicolae Bălcescu High-School, Cluj-Napoa (Romania), 2016 Contents Children’s Literature 5 What’s for supper tonight? Mary Bardet 5 Of Neverland and Young Adult Spaces in Contemporary Dystopias Anna Bugajska 12 When do you stop being a young adult and start being an adult? Virginie Douglas 24 Responding to Ian Falconer’s Olivia Saves the Circus (2000) Maria Emmanouilidou 36 The Provision of Children’s Literature at Bishop Grosseteste University (Lincoln) Sibylle Erle and Janice Morris 49 The Wickedness of Feminine Evil in the Harry Potter Series Eliana Ionoaia 55 The Moral Meets the Marvellous Nada Kujundžić 68 Nursery rhymes Catalina Millán 81 Tales of Long Ago as a link between cultures Smiljana Narančić Kovač 93 Once a Riddle, Always a Riddle Marina Pirlimpou 108 The Immigrant Girl and the Western Boyfriend Anna Stibe and Ulrika Andersson Hval 122 Reviews 133 Aimee Pozorski. Roth and Trauma: The Problem of History in the Later Works (1995-2010). London and New York: Continuum, 2011. 133 David Gooblar. The Major Phases of Philip Roth. -

1 CHAPTER I INTRODUCTION A. Research Background Film Or

perpustakaan.uns.ac.id digilib.uns.ac.id 1 CHAPTER I INTRODUCTION A. Research Background Film or movie is one of entertainments that many people mostly like. Movies are usually broadcasted through television, internet, cinema, and in the form VCD or DVD as a popular form of entertainment for parents, teenagers and kids. Along its development, movies do not only serve as entertainment; movies are usually used as an education medium for children. Especially English movies now are available in many countries around the world. The English movies help children to motivate and increase their vocabulary and ability in speaking English. Film also teaches them how to use proper word in the right context. Therefore, the translator especially film translator has role to provide people need in understanding film content. Translation basically is the process of transferring messages from a source language to a target language, in the form of speech or writing and oral. In the process, the translator also shifts the culture. Generally, translation is in the form of written or printed text, such translation for book, novel or document. But film’s or movie’s translation is different; it is called subtitling or dubbing. Within the existence of subtitle and dubbing, both of them are translation terms for translating language in audio visual communication media forms such as in a film, or television’s program. According to Karamitroglou, subtitle can be defined as the translation of the spoken (written)commit tosource user text of film product into a written perpustakaan.uns.ac.id digilib.uns.ac.id 2 target text which is added onto the images of the original product, usually at the bottom of the screen. -

Peter Pan, “Why Fear Death? It Is the Most Beautiful Adventure That Life Gives Us.”

A Reader's Guide ON THE SAME PAGE 2020 MADISON LIBRARY DISTRICT Sir James Matthew Barrie, 1st Baronet James Barrie, often referred to as J.M. Barrie, was the ninth of ten children born to David Barrie, a hand weaver, and the former Margaret (Mary) Ogilvy in Kirriemuir, Scotland on May 9, 1860. Little Jamie had a complicated relationship with the matriarch of this strict Calvinist family. His maternal grandmother had died when Mary was eight, leaving her to run the large household. She had no real childhood of her own which may have tainted her relationships with her children. Mary had a very clear favorite, Jamie’s older brother David. When Jamie was six and David fourteen, David was killed in an ice skating accident, and Mary plummeted into an emotional abyss. Attempting to gain her love and give her some consolation, little Jamie began dressing in his dead brothers clothes, tried to act like him, give his familiar whistles, etc. At one point, he walked into a room where his mother was sitting in the dark, her eyes grew large and she asked, “Is that you?” to which Jamie replied, “No, it’s no him; it’s just me.” The only thing that seemed to give his mother any comfort was knowing that David would never grow up and leave her behind. Jamie was a small child, short (Even as an adult, he never passed five feet three inches.) and slight who drew attention to himself through storytelling. He spent much of his school years in Glasgow where his two oldest siblings, Mary Ann and Alexander, taught at the academy. -

Growing Sideways: Challenging Boundaries Between Childhood and Adulthood in Twenty-First Century Britain

DOCTORAL THESIS Growing sideways challenging boundaries between childhood and adulthood in twenty-first century Britain Malewski, Anne Award date: 2019 General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal ? Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 29. Sep. 2021 Growing Sideways: Challenging Boundaries Between Childhood and Adulthood in Twenty-First Century Britain by anne malewski BA, MA A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of PhD Department of English & Creative Writing University of Roehampton 2018 . Snail human by author, 2018 Abstract This thesis examines changing boundaries between childhood and adulthood in twenty-first century British society and culture through the concept of growth in order to investigate alternatives to conventional ideas of growing up. It is the first in-depth academic study to consider growing sideways as a distinct and important discourse that challenges, and provides an alternative to, the discourse of upwards growth, previously identified as a pervasive grand narrative that privileges adulthood (Trites, 2014). -

“To Die Would Be an Awfully Big Adventure”: the Enigmatic Timelessness of Peter Pan’S Adaptations

To die would be an awfully... 93 “TO DIE WOULD BE AN AWFULLY BIG ADVENTURE”: THE ENIGMATIC TIMELESSNESS OF PETER PAN’S ADAPTATIONS Deborah Cartmell Imelda Whelehan Montfort University Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone can be seen, on one level, as a critique of the attractiveness of Peter Pan’s eternal youthfulness. Indeed, J.K. Rowling, through Professor Dumbledore, rewrites Peter Pan’s famous comment, “to die would be an awfully big adventure” to “to a well-organised mind, death is but the next great adventure” (Rowling, 1997: 215). In order for the story to reach to a happy conclusion, the elixir of youth must be destroyed and the passage of time acknowledged. Contrary to the countless adaptations of Peter Pan, Barrie’s Edwardian narrative has much in common with this perspective: the myth of timelessness is, indeed, a dangerous one. Originally written as a play in 1904, the success of Peter Pan was and is phenomenal. It is a story that is completely open to adaptation and its origins in drama particularly lend it to the medium of film. It brings together three popular genres in children’s fiction: the adventure story for boys, the domestic story and the fairy tale. Restricting ourselves to four adaptations of the text - the 1911 novelization, the 1953 Disney adaptation, Steven Spielberg’s Hook (1991) and Disney’s sequel, Return to Never Land (2002) - we will consider four very different constructions of time and timelessness and show how the trope of childhood innocence is appropriated for 94 Deborah Cartmell & Imelda Whelehan quite different purposes in each version. -

In Order of Release

Animated(in order Disney of release) Movies Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs Treasure Planet Pinocchio The Jungle Book 2 Dumbo Piglet's Big Movie Bambi Finding Nemo Make Mine Music Brother Bear The Adventures of Ichabod and Mr. Toad Teacher's Pet Cinderella Home on the Range Alice in Wonderland The Incredibles Peter Pan Pooh's Heffalump Movie Lady and the Tramp Valiant Sleeping Beauty Chicken Little One Hundred and One Dalmatians The Wild The Sword in the Stone Cars The Jungle Book The Nightmare Before Christmas 3D TNBC The Aristocats Meet the Robinsons Robin Hood Ratatouille The Many Adventures of Winnie the Pooh WALL-E The Rescuers Roadside Romeo The Fox and the Hound Bolt The Black Cauldron Up The Great Mouse Detective A Christmas Carol Oliver & Company The Princess and the Frog The Little Mermaid Toy Story 3 DuckTales: Treasure of the Lost Lamp Tangled The Rescuers Down Under Mars Needs Moms Beauty and the Beast Cars 2 Aladdin Winnie the Pooh The Lion King Arjun: The Warrior Prince A Goofy Movie Brave Pocahontas Frankenweenie Toy Story Wreck-It Ralph The Hunchback of Notre Dame Monsters University Hercules Planes Mulan Frozen A Bug's Life Planes: Fire & Rescue Doug's 1st Movie Big Hero 6 Tarzan Inside Out Toy Story 2 The Good Dinosaur The Tigger Movie Zootopia The Emperor's New Groove Finding Dory Recess: School's Out Moana Atlantis: The Lost Empire Cars 3 Monsters, Inc. Coco Return to Never Land Incredibles 2 Lilo & Stitch Disney1930s - 1960s (in orderMovies of release) Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs Ten Who Dared Pinocchio Swiss Family Robinson Fantasia One Hundred and One Dalmatians The Reluctant Dragon The Absent-Minded Professor Dumbo The Parent Trap Bambi Nikki, Wild Dog of the North Saludos Amigos Greyfriars Bobby Victory Through Air Power Babes in Toyland The Three Caballeros Moon Pilot Make Mine Music Bon Voyage! Song of the South Big Red Fun and Fancy Free Almost Angels Melody Time The Legend of Lobo So Dear to My Heart In Search of the Castaways The Adventures of Ichabod and Mr.