2 the Underfloor Assemblage of the Hyde Park Barracks

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Concert in the Australian Bush Was Already Going Strong When

Three Days in While the acoustics of the bush may not be as fine-tuned as those of the Sydney Opera House, the outdoor chorus played up the interconnectivity of SYDNEY music and nature much like a performance of John Cage’s 1972 composition, ‘Bird Cage’. The avant- The concert in the Australian bush was garde composer pioneered indeterminacy in music already going strong when we arrived. and described the need for a space in which “people are free to move and birds to fly.” Easy to do when By Monica Frim there’s not a bad seat in the bush. All you have to do Visitors aboard the Photography by John and Monica Frim Skyway thrill to is show up. 360-degree views of Enter Blue Mountains Tours, a family–owned the Jamison Valley Magpies warbled and trilled, mynah birds whistled and wailed, white crested as they glide toward cockatoos screeched out a raucous chorus from their various perches—picnic tables, company headed by Graham Chapman that picks up Scenic World in the day-trippers from their hotels in Sydney and takes Blue Mountains of eucalyptus trees and even the patchy grass at our feet. Kookaburras joined in New South Wales. them on small-group tours to the Blue Mountains. with their laughter, while we, a motley troop of wayfarers from various parts of Only 40 miles west of Australia’s capital city, the world, tucked into an Aussie bush breakfast of fried eggs and ham in a bun. Blue Mountains National Park is part of the Blue Nature’s open air concert hall permitted food but it came with peril: thieving birds Graham Chapman of Blue Mountains Tours, poses with that brazenly swooped and swiped at the provisions in our hands, the sounds of a kangaroo in the background during a bush walk in the Blue Mountains. -

SYDNEY OPERA HOUSE TM Sydney, New South Wales, Australia

SYDNEY OPERA HOUSE TM Sydney, New South Wales, Australia Booklet available in English on Heft in deutscher Sprache erhältlich auf Livret disponible en français sur Folleto disponible en español en Folheto disponível em português em A füzet magyarul ezen a honlapon olvasható: Architecture.LEGO.com www.sydneyoperahouse.com 21012_BI.indd 1 13/10/2011 12:08 PM SYDNEy OpERa HOUSE™ Sydney Opera House is a masterpiece of late The massive concrete sculptural shells that form modern architecture and an iconic building of the 20th the roof of Sydney Opera House appear like billowing century. It is admired internationally and proudly treasured sails filled by the sea winds with the sunlight and cloud by the people of Australia. It was created by a young shadows playing across their shining white surfaces. Danish architect, Jørn Utzon (1918-2008), who understood Utzon envisaged it as being like to a Gothic cathedral the potential provided by the site against the stunning that people would never tire of and never be finished with. backdrop of Sydney Harbour. Today Sydney Opera House does not operate solely as a venue for opera or symphony, but also hosts a wide range of performing arts and community activities. These include classical and contemporary music, ballet, opera, theatre, dance, cabaret, talks and large scale public programs. Since its opening in 1973 over 45 million people have attended more than 100 000 performances, and it is estimated that well over 100 million people have visited the site. It is one of Australia's most visited tourist attractions, being the most internationally recognized symbol of the nation. -

An Exploration of Bennelong Point

Australian history presentation using the interactive whiteboard An exploration of Bennelong Point Stage 2 Year 4 Syllabus outcome: ENS2.5 Describes places in the local area and other parts of Australia and explains their significance Indicators: - Significant natural, heritage and built features in the local area, NSW and Australia and their uses - Groups associated with places and features including Aboriginal people 1 2 3 4 5 Not quite Try Again 6 Not quite Try Again 7 Not quite Try Again 8 9 10 Not quite Try Again 11 WellDone!Youhavefound BennelongPoint 12 Time to take a trip in our.. 13 Welcome You have gone back in time to l l l l l l u u find yourself on the first fleet, P u P P to just before it arrived in Sydney Harbour. The captain has asked you to draw a map of what they are likely to expect when they 1788 reach harbour. Pullll Considering you are from 2012 and have an idea of what it looks like in present day... Createamapthatoutlineswhat SydneyHarbourcouldhavelookedlike in1788. 14 Whatwastherewhen Aboriginal small tidal island theyarrived? oyster shells The area currently known as Bennelong Point originally a _________________ that was scattered with discarded ___________ that had been collected by local ___________ women over hundreds of years. Also... These shells were soon gathered by early settlers and melted down to create lime for cement mortar which was used to build the two-story government house. 15 l l l Whoorwhatdoyouthinkwasthere l u u The Eora people, a group of indigenous Australians, P P lived in the region of Sydney cove. -

Sydney Opera House (SOH) – Attended Construction Noise Measurements – 30Th November 2020

Sydney Opera House (SOH) – Attended Construction Noise Measurements – 30th November 2020 Sydney Opera House Bennelong Point Report Reference: 20164 Sydney Opera House – Attended Construction Noise Measurements – 2020-11-30 - Revision 1 8 December 2020 Project Number: 20164 Version: Revision 1 Sydney Opera House 8 December 2020 Bennelong Point Revision 1 Sydney Opera House (SOH) – Attended Construction Noise Measurements – 30th November 2020 PREPARED BY: Pulse Acoustic Consultancy Pty Ltd ABN 61 614 634 525 Level 5, 73 Walker Street, North Sydney, 2060 Alex Danon Mob: +61 452 578 573 E: [email protected] www.pulseacoustics.com.au This report has been prepared by Pulse Acoustic Consultancy Pty Ltd with all reasonable skill, care and diligence, and taking account of the timescale and resources allocated to it by agreement with the Client. Information reported herein is based on the interpretation of data collected, which has been accepted in good faith as being accurate and valid. This report is for the exclusive use of Sydney Opera House No warranties or guarantees are expressed or should be inferred by any third parties. This report may not be relied upon by other parties without written consent from Pulse Acoustic. Pulse Acoustic disclaims any responsibility to the Client and others in respect of any matters outside the agreed scope of the work. DOCUMENT CONTROL Reference Status Date Prepared Checked Authorised 20164 Sydney Opera House – Attended Construction Final 8th December Alex Danon Alex Danon Matthew Harrison Noise Measurements – 2020-11-30 - Revision 1 2020 Pulse Acoustic Consultancy Pty Ltd Page 2 of 18 Sydney Opera House 8 December 2020 Bennelong Point Revision 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................................... -

Ferry Safety Investigation Report Close Quarters Incident Involving Mv

FERRY SAFETY INVESTIGATION REPORT CLOSE QUARTERS INCIDENT INVOLVING MV NARRABEEN AND BARQUENTINE SOUTHERN SWAN SYDNEY HARBOUR 17 MAY 2013 Released under the provisions of Section 45C (2) of the Transport Administration Act 1988 and 46BBA (1) of the Passenger Transport Act 1990 Investigation Reference 04603 FERRY SAFETY INVESTIGATION CLOSE QUARTERS INCIDENT INVOLVING MV NARRABEEN AND BARQUENTINE SOUTHERN SWAN SYDNEY HARBOUR 17 MAY 2013 Released under the provisions of Section 45C (2) of the Transport Administration Act 1988 and 46BBA (1) of the Passenger Transport Act 1990 Investigation Reference 04603 Published by: The Office of Transport Safety Investigations Postal address: PO Box A2616, Sydney South, NSW 1235 Office location: Level 17, 201 Elizabeth Street, Sydney NSW 2000 Telephone: 02 9322 9200 Accident and incident notification: 1800 677 766 Facsimile: 02 9322 9299 E-mail: [email protected] Internet: www.otsi.nsw.gov.au This Report is Copyright. In the interests of enhancing the value of the information contained in this Report, its contents may be copied, downloaded, displayed, printed, reproduced and distributed, but only in unaltered form (and retaining this notice). However, copyright in material contained in this Report which has been obtained by the Office of Transport Safety Investigations from other agencies, private individuals or organisations, belongs to those agencies, individuals or organisations. Where use of their material is sought, a direct approach will need to be made to the owning agencies, individuals or organisations. Subject to the provisions of the Copyright Act 1968, no other use may be made of the material in this Report unless permission of the Office of Transport Safety Investigations has been obtained. -

Amendments to Sydney Development Control Plan 2012 – Central Sydney Planning Strategy Amendment

ATTACHMENT D ATTACHMENT D AMENDMENTS TO SYDNEY DEVELOPMENT CONTROL PLAN 2012 – CENTRAL SYDNEY PLANNING STRATEGY AMENDMENT Sydney2030 / Sydney Green / Global / Development Connected Control Plan 2012 Central Sydney Planning Strategy Amendment 2016 Sydney DCP 2012 – Central Sydney Planning Review Amendment Draft April 2013 1 Sydney DCP 2012 – Central Sydney Planning Review Amendment SYDNEY DEVELOPMENT CONTROL PLAN 2012 – CENTRAL SYDNEY PLANNING REVIEW AMENDMENT 1. The purpose of the Development Control Plan The purpose of this Development Control Plan (DCP) is to amend the Sydney Development Control Plan 2012 (SDCP2012), adopted by Council on 14 May 2012 and which came into effect on 14 December 2012. The draft provisions progress key planning controls proposed in the City of Sydney’s Central Sydney Planning Strategy (the Strategy). The provisions relate only to those matters to be contained in the SDCP2012, with supporting planning controls contained in the Central Sydney Planning Proposal which has been prepared concurrently with this DCP. For a more complete understanding of the land use and planning controls being proposed for Central Sydney, this draft DCP should be read in conjunction with the Planning Proposal, the Strategy, its technical appendices and other supporting documentation. The proposed provisions in this DCP constitute the initial phase of amendments to SDCP2012 and reflect the priority actions identified in the Strategy. 2. Citation This amendment may be referred to as the Sydney Development Control Plan 2012 – Central Sydney Planning Review Amendment. 3. Land Covered by this Plan This plan applies to land identified as ‘Central Sydney’ on the SLEP2012 Locality and Site Identification Map. This land is shown in pink in Figure I below. -

Phillip and the Eora Governing Race Relations in the Colony of New South Wales

Phillip and the Eora Governing race relations in the colony of New South Wales Grace Karskens In the Botanic Gardens stands a grand monument to Arthur Phillip, the first governor of New South Wales. Erected 1897 for the Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee, the elaborate fountain encapsulates late nineteenth century ideas about society and race. Phillip stands majestically at the top, while the Aboriginal people, depicted in bas relief panels, are right at the bottom. But this is not how Phillip acted towards Aboriginal people. In his own lifetime, he approached on the same ground, unarmed and open handed. He invited them into Sydney, built a house for them, shared meals with them at his own table.1 What was Governor Arthur Phillip's relationship with the Eora, and other Aboriginal people of the Sydney region?2 Historians and anthropologists have been exploring this question for some decades now. It is, of course, a loaded question. Phillip's policies, actions and responses have tended to be seen as a proxy for the Europeans in Australia as whole, just as his friend, the Wangal warrior Woolarawarre Bennelong, has for so long personified the fate of Aboriginal people since 1788.3 The relationship between Phillip and Bennelong has been read as representing not only settler-Aboriginal relations in those first four years but as the template for the following two centuries of cross-cultural relations. We are talking here about a grand narrative, driven in part by present-day moral conscience, and deep concerns about on-going issues of poverty, dysfunction and deprivation in many Aboriginal communities, about recognition of and restitution for past wrongs and about reconciliation between black and white Australians. -

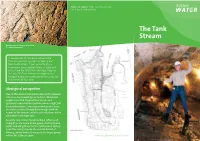

The Tank Stream Today

Front cover photo: In the Tank Stream today. Photograph: Sydney Water. The Tank Stream Mason’s marks in the block work inside the Tank Stream tunnel. In recognition of the importance of the Tank Stream to the people of Sydney and New South Wales, it was protected by a Permanent Conservation Order in 1989 and entered on the NSW State Heritage Register in 1999. The Tank Stream is recognised as being of national importance to the European settlement of Australia. Aboriginal occupation Due to the almost immediate impact of European colonists, our knowledge of Sydney’s Aboriginal people is limited. Early settlers casual and systematic observations provide some insight, but basic information is missing or ambiguous. Even the names of the Aboriginal landscape with the names of the stream and the other features in the catchment have been lost. Recently researchers favour Gadigal (often spelt Cadigal) as the name of the group that had some rights and obligations for the land around Sydney Cove. The Gadigal spoke the coastal dialect of Dharug, which makes them part of a larger group within the Sydney region. SW94 09/10 Printed on recycled paper John Skinner Prout, The Tank Stream, Sydney, circa 1842. A tour group inspects the Tank Stream. pencil,watercolour, opaque white highlights, 25.5 x 37.5cm Purchased 1913 Collection: Art Gallery of NSW The Tank Stream runs underground from near Hyde Park to Circular Quay. Photograph: Brenton McGeachie of AGNSW ydney’s first water supply As the water source for both humans and their Major Grose made a significant environmental livestock, it was essential to maintain water quality decision. -

Sydney Tours

MMC Inclusive Private Sydney Australia Tours - Hotel – Transportation - March 16-18, 2021 Day 1 Tuesday March16th- Arrive Sydney-Sightseeing Upon disembarkation, you will be met by your local guide who will accompany you to your private coach for your Full Day City Sights Tour. Drive through the historic 'Rocks' area where Australia was first founded with its maze of terrace houses, restored warehouses, pubs and restaurants. Drive under the famous 'coat hanger', the Sydney Harbour Bridge and view Sydney's famous architectural masterpiece, the Sydney Opera House. Continue through the commercial area of the city passing the historical buildings of Macquarie Street – Parliament House, The Mint and Hyde Park Barracks. Alight at Mrs Macquarie's Chair for breathtaking views of the city and harbour. Proceed through cosmopolitan Kings Cross and exclusive garden suburbs to the Gap on the ocean headland at Watsons Bay. Return to the city via famous Bondi Beach and Paddington, a Victorian suburb of restored terrace houses richly decorated with cast-iron lace. Tour highlights in above itinerary maybe in different order due to traffic conditions. Your coach will then drop you off near Circular Quay and your guide will lead you to Jetty 6 to board your lunch cruise with Captain Cook Cruises. Depart Circular Quay for your cruise of Sydney Harbour which most travel experts agree is one of the most scenic harbours in the world. You will see spectacular views of Sydney Harbour Bridge, Circular Quay, The Rocks, Opera House, Fort Denison, Point Piper, Watson's Bay. See Sydney's foreshore parkland and many stately homes. -

Sydney Opera House Forecourt Excavation

Sydney Opera House Forecourt Excavation Historical Archaeological Assessment and Management Plan Report prepared for Sydney Opera House June 2018 Sydney Office Level 6 372 Elizabeth Street Surry Hills NSW Australia 2010 T +61 2 9319 4811 Canberra Office 2A Mugga Way Red Hill ACT Australia 2603 T +61 2 6273 7540 GML Heritage Pty Ltd ABN 60 001 179 362 www.gml.com.au GML Heritage Report Register The following report register documents the development and issue of the report entitled Sydney Opera House Forecourt Excavation—Historical Archaeological Assessment and Management Plan, undertaken by GML Heritage Pty Ltd in accordance with its quality management system. Job No. Issue No. Notes/Description Issue Date 18-0311 1 Draft Report 25 May 2018 18-0311 2 Final Report 22 June 2018 Quality Assurance GML Heritage Pty Ltd operates under a quality management system which has been certified as complying with the Australian/New Zealand Standard for quality management systems AS/NZS ISO 9001:2008. The report has been reviewed and approved for issue in accordance with the GML quality assurance policy and procedures. Project Manager: Dr Tim Owen Project Director & Reviewer: Abi Cryerhall Issue No. 2 Issue No. 2 Signature Signature Position: Senior Associate Position: Senior Associate Date: 22 June 2018 Date: 22 June 2018 Copyright Historical sources and reference material used in the preparation of this report are acknowledged and referenced at the end of each section and/or in figure captions. Reasonable effort has been made to identify, contact, acknowledge and obtain permission to use material from the relevant copyright owners. -

Sydney Opera House (SOH) – Attended Construction Noise Measurements – 4Th December 2020

Sydney Opera House (SOH) – Attended Construction Noise Measurements – 4th December 2020 Sydney Opera House Bennelong Point Report Reference: 20164 Sydney Opera House – Attended Construction Noise Measurements – 2020-12-04 - Revision 1 8 December 2020 Project Number: 20164 Version: Revision 1 Sydney Opera House 8 December 2020 Bennelong Point Revision 1 Sydney Opera House (SOH) – Attended Construction Noise Measurements – 4th December 2020 PREPARED BY: Pulse Acoustic Consultancy Pty Ltd ABN 61 614 634 525 Level 5, 73 Walker Street, North Sydney, 2060 Alex Danon Mob: +61 452 578 573 E: [email protected] www.pulseacoustics.com.au This report has been prepared by Pulse Acoustic Consultancy Pty Ltd with all reasonable skill, care and diligence, and taking account of the timescale and resources allocated to it by agreement with the Client. Information reported herein is based on the interpretation of data collected, which has been accepted in good faith as being accurate and valid. This report is for the exclusive use of Sydney Opera House No warranties or guarantees are expressed or should be inferred by any third parties. This report may not be relied upon by other parties without written consent from Pulse Acoustic. Pulse Acoustic disclaims any responsibility to the Client and others in respect of any matters outside the agreed scope of the work. DOCUMENT CONTROL Reference Status Date Prepared Checked Authorised 20164 Sydney Opera House – Attended Construction Final 8th December Alex Danon Alex Danon Matthew Harrison Noise Measurements – 2020-12-04 - Revision 1 2020 Pulse Acoustic Consultancy Pty Ltd Page 2 of 24 Sydney Opera House 8 December 2020 Bennelong Point Revision 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................................... -

Conservation Issues the Obelisk Macquarie Place

CONSERVATION ISSUES THE OBELISK MACQUARIE PLACE SYDNEY 1840s 1890s 1930s For City of Sydney August 2003 CASEY & LOWE Pty Ltd Archaeology & Heritage ________________________________________________________________________________ 420 Marrickville Road, Marrickville NSW 2204 • Tel: (02) 9568 5375 Fax: (02) 9572 8409 • Mobile: 0419 683 152 • E-mail: [email protected] i EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Results . The Obelisk, Macquarie Place has a State level of heritage significance. The obelisk’s individual level of significance and its significance to the place warrants its conservation in situ. The obelisk is in a state of decay that involves the continuing loss of inscriptions and fabric. Drummy surfaces have exfoliated since last recorded in 1997. Research has shown that there has been replacement of the two base courses, recutting of the inscription, a stone indent replacing one section of an inscription and large drill holes. While many reports have been written in the last 30 years very little substantive conservation works have been undertaken on the monument. The long-term conservation of this monument of exceptional significance requires the Council of the City of Sydney to act speedily to implement a program of conservation. Council has a Conservation Plan endorsed by the NSW Heritage Council. The endorsed option is to conserve the obelisk in situ. Recommendations Recommended Option 1. This report recommends that the Obelisk, Macquarie Place should be conserved in situ and maintained (Option 3). 2. The obelisk’s condition will need to be monitored and managed through a maintenance program. 3. The City of Sydney should adopt and endorse the recommended option of this report to conserve the obelisk in situ and maintain it into the future.