Proquest Dissertations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ebooksspringer Contrat 4903.07.Xls Title Editors/Authors Year Book ISBN13 Book E-ISBN13 the Abcs of Gene Cloning Wong, Dominic W

EbooksSpringer_contrat_4903.07.xls Title Editors/Authors Year Book ISBN13 Book e-ISBN13 The ABCs of Gene Cloning Wong, Dominic W.S. 2006 978-0-387-28663-1 978-0-387-28679-2 Abductive Reasoning Aliseda, Atocha 2006 978-1-4020-3906-5 978-1-4020-3907-2 Abeta Peptide and Alzheimer's Disease Barrow, Colin J; Small, David H. 2007 978-1-85233-961-6 978-1-84628-440-3 Abiotic Stress Tolerance in Plants Rai, Ashwani K.; Takabe, Teruhiro 2006 978-1-4020-4388-8 978-1-4020-4389-5 Abnormal Skeletal Phenotypes Castriota-Scanderbeg, Alessandro; 2005 978-3-540-67997-4 978-3-540-30361-9 Dallapiccola, Bruno Abord clinique des malades de l'alcool Huas, Dominique; Rueff, Bernard 2005 978-2-287-59769-5 978-2-287-28577-6 Abord clinique des urgences traumatiques au cabinet Carolet, Carole; Pire, Jean-Claude 2005 978-2-287-25170-2 978-2-287-28164-8 du généraliste Abord clinique du malade âgé Moulias, Robert 2007 978-2-287-22084-5 978-2-287-31016-4 Abord clinique en urologie Cortesse, Alain; LeDuc, Alain 2006 978-2-287-25253-2 978-2-287-48614-2 About Life Agutter, Paul S.; Wheatley, Denys N. 2007 978-1-4020-5417-4 978-1-4020-5418-1 Abstract Algebra Grillet, Pierre Antoine 2007 978-0-387-71567-4 978-0-387-71568-1 Abstract Computing Machines Kluge, W. 2005 978-3-540-21146-4 978-3-540-27359-2 Abstract Harmonic Analysis of Continuous Wavelet Führ, Hartmut 2005 978-3-540-24259-8 978-3-540-31552-0 Transforms Abstraction Refinement for Large Scale Model Hachtel, Gary D.; Somenzi, Fabio; Wang, 2006 978-0-387-34155-2 978-0-387-34600-7 Abstraction,Checking Refinement and Proof for Probabilistic McIver,Chao Annabelle; Morgan, Charles C. -

Seeking to Understand

Spring 2017 Seeking to Understand Students and alumnae journey to find truth PB | Spring 2017 Courier | 1 page 4 page 8 page 10 page 14 page 45 TABLE of CONTENTS volume 92, number 1 | spring 2017 Features Seeking to Understand . 4 Finding Peace and Embracing Vulnerability . 8 Building Community Through Laughter . 10 Getting to Know You Over Coffee . 12 Treating Others as Worthy of Love . 14 When Ministry Meets Passion . 20 Departments 2 . Upon Reflection For the Record . 23. 17 . Belles Athletics Club News . 25. 18 . Avenue News Class News . 27. 20 . Making a Difference Excelsior . .44 22 . In Memoriam Closing Belle . .45 On the cover and inside cover: Itzxul Moreno ’17 carried this backpack, containing supplies including food, water, and first-aid kits for individuals crossing the border into the US. See page 5 to read her story. Multimedia content can be found online at saintmarys.edu/Courier The Saint Mary’s College Courier Shari Rodriguez Courier Staff Emerald Blankenship ’17 About Saint Mary’s College is published three times a year Vice President for Gwen O’Brien Kathe Brunton Saint Mary’s College is a Catholic, Editor Claire Condon ’17 by Saint Mary’s College, Notre College Relations residential, women’s undergraduate Dame IN 46556-5001. [email protected] [email protected] Claire Kenney ’10 Kelly Konya ’15 college in the liberal arts tradition, Art Wager Nonprofit postage paid at the Post Contributors founded by the Sisters of the Holy Alumnae Relations Staff Creative Director Office at Notre Dame, IN 46556 Cross in 1844. The College offers Kara O’Leary ’89 Class News and at additional mailing offices. -

Class of 2020

Class of 2020 Byblos Campus Academic Officers President Dr. Joseph G. Jabbra Provost Dr. Georges E. Nasr School of Arts & Sciences Dr. Cathia Jenainati Dean Adnan Kassar School of Business Dr. Wassim Shahin Dean School of Architecture & Design Dr. Elie Haddad Dean School of Engineering Dr. Lina Karam Dean School of Pharmacy Dr. Imad Btaiche Dean Alice Ramez Chagoury Dr. Costantine Daher School of Nursing Interim Dean Gilbert and Rose-Marie Chagoury Dr. Michel E. Mawad School of Medicine Dean ALMA MATER We greet thee, O College fair, In the Shadow of Lebanon, Where its mystic haze doth melt In the Mediterranean sea. CHORUS: Alma Mater, hail to thee, Receive our pledge of constancy Alma Mater, hail to thee, Deep loyalty we vow. To thy portals, O College fair, We thy students have come from far, We have answered thy call to dare, To adventure beneath thy star. By the light of thy holy fires, We shall follow the way of truth; In the strength of our new desires, We pledge to thee all our youth. (Sung to the tune of “Follow the Gleam”) Awardees 2019- 2020 School of Arts & Sciences Jana Oussama Dib El Jalbout Valedictorian Christelle Elias Barakat President Award Rhea Ghazy Wakim Torch Award and Rhoda Orme Award Adnan Kassar School of Business Wendy Toni El Hage President Award Jude Manhal Darwich Torch Award School of Architecture & Design Rihab Maan Soukkarieh President Award Georges Antoine Eid Torch Award School of Engineering Joelle Bachir El Sayegh President Award Johnny Joseph Sawma Awad Torch Award Joseph Elias Chakar The Charbel Khairallah -

The Swiss in Southern Africa 1652-1970

ADOLPHE LINDER THE SWISS IN SOUTHERN AFRICA 1652-1970 PART I ARRIVALS AT THE CAPE 1652-1819 IN CHRONOLOGICAL SEQUENCE Originally published 1997 by Baselr Afrika Bibliographien, Basel Revised for Website 2011 © Adolphe Linder 146 Woodside Village 21 Norton Way Rondebosch 7700 South Africa Paper size 215x298 mm Face 125x238 Font Times New Roman, 10 Margins Left and right 45 mm, top and bottom 30 mm Face tailored to show full page width at 150% enlargement 1 CONTENTS 1. Prologue ………………………………………………………………………………2 2. Chronology 1652-1819 ……………………………………………………………….6 3. Introduction 3.1 The spelling of Swiss names ………………………………………………….6 3.2 Swiss origine of arrivals………………………………………………………..7 3.3 Location of Swiss at the Cape…………………………………………………..8 3.4 Local currency …………………………………………………………………8 3.5 Glossary ………………………………………………………………………..8 4. Short history of arrivals during Company rule 1652-1795 4.1 Establishment of the settlement at the Cape…………………………………….10 4.2 The voyage to the Cape …………………………………………………………10 4.3 Company servants……………………………………………………………….12 4.4 Swiss labour migration to the Netherlands ……………………………………..12 4.5 Recruitment for the Company …………………………………………………..17 4.6 In Company service …………………………………………………………….17 4.7 Freemen………………………………………………………………………….22 4.8 Crime and punishment ………………………………………….…………….. 25 4.9 The Swiss Regiment Meuron at the Cape 1783-1795 …………………………..26 4.10 The end of the Dutch East India Company ……………………………………..29 4.11 Their names live on …………………………………………………………….29 5. Summary of Swiss arrivals during First British Occupation 1695-1803…………….29 6. Summary of Swiss arrivals during Batavian rule 1803-1806 ………………………30 7. Summary of Swiss arrivals during first fourteen years of British colonial rule, 1806-1819……………………………………………………………………………30 8. Personalia 1652-1819 ……………………………………………………………….31 9. -

ELEGANT REMAINS of an ILLUMINATED BREVIARY from PARIS Portable Breviary (Augustinian Use) in Latin, Manuscript on Parchment Northern France, Paris?, C

BOOK OF HOURS 1. BY ONE OF THE MOST SKILLFUL PAINTERS OF HIS GENERATION Book of Hours (Use of Paris) In Latin and French, illuminated manuscript on parchment France, Paris, c. 1460-1470 15 large miniatures and 6 historiated initials by an artist in the circle of the Coëtivy Master This is an undoubtedly Parisian Book of Hours, and it is attributed to an artist in the circle of the Coëtivy Master, deemed “the most important artist practicing in Paris in the third quarter of the century.” The inclusion of French prayers (or poems) and historiated initials for the virgin Saints Genevieve and Avia before the Hours of the Virgin and the richness of the bor- ders hint that it could have been made to order as a commission. The borders are richly decorated with sprays and knots of acanthus and abundant flowers, fruits, and birds, with clusters of strawberries throughout. BOH 168 • $100,000 2. EVERYDAY PIETY PRACTICED IN A FLEMISH HOUSEHOLD Book of Hours (Use of Rome?) In Latin, illuminated manuscript on parchment Southern Netherlands, Ghent or Bruges, c. 1480 4 full-page miniatures; 8 historiated initials Homespun realism characterizes this Book of Hours from the southern Netherlands. Painted by three artists, the manu- script is in fine condition with full-page pictures with generous margins and full-page pictures introducing the main textual sections. A Dutch-influenced artist painted one miniature and a historiated initial. A Flemish artist contributed the other full- page pictures. And, the animated and charming historiated initials are by a third hand. BOH 159 • $80,000 3. -

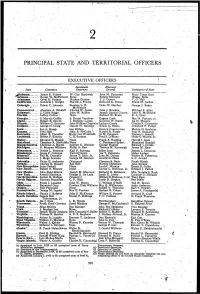

State and Territorial Officers

r Mf-.. 2 PRINCIPAL STATE AND TERRITORIAL OFFICERS EXECUTIVE- OFFICERS • . \. Lieutenant Attorneys - Siaie Governors Governors General Secretaries of State ^labama James E. Folsom W. Guy Hardwick John M. Patterson Mary Texas Hurt /Tu-izona. •. Ernest W. McFarland None Robert Morrison Wesley Bolin Arkansas •. Orval E. Faubus Nathan Gordon T.J.Gentry C.G.Hall .California Goodwin J. Knight Harold J. Powers Edmund G. Brown Frank M. Jordan Colorajlo Edwin C. Johnson Stephen L. R. Duke W. Dunbar George J. Baker * McNichols Connecticut... Abraham A. Ribidoff Charles W. Jewett John J. Bracken Mildred P. Allen Delaware J. Caleb Boggs John W. Rollins Joseph Donald Craven John N. McDowell Florida LeRoy Collins <'• - None Richaid W. Ervin R.A.Gray Georgia S, Marvin Griffin S. Ernest Vandiver Eugene Cook Ben W. Fortson, Jr. Idaho Robert E. Smylie J. Berkeley Larseri • Graydon W. Smith Ira H. Masters Illlnoia ). William G. Stratton John William Chapman Latham Castle Charles F. Carpentier Indiana George N. Craig Harold W. Handlpy Edwin K. Steers Crawford F.Parker Iowa Leo A. Hoegh Leo Elthon i, . Dayton Countryman Melvin D. Synhorst Kansas. Fred Hall • John B. McCuish ^\ Harold R. Fatzer Paul R. Shanahan Kentucky Albert B. Chandler Harry Lee Waterfield Jo M. Ferguson Thelma L. Stovall Louisiana., i... Robert F. Kennon C. E. Barham FredS. LeBlanc Wade 0. Martin, Jr. Maine.. Edmund S. Muskie None Frank Fi Harding Harold I. Goss Maryland...;.. Theodore R. McKeldinNone C. Ferdinand Siybert Blanchard Randall Massachusetts. Christian A. Herter Sumner G. Whittier George Fingold Edward J. Cronin'/ JVflchiitan G. Mennen Williams Pliilip A. Hart Thomas M. -

ILR Consolidated Table of Cases

CONSOLIDATED TABLE OF CASES ARRANGED ALPHABETICALLY VOLUMES 1—125 Notes : This table of cases lists as comprehensively as possible, in alphabetical order, all cases reproduced or reported in the Annual Digest /International Law Reports, entering cases under all common variants of their title. It should be noted that many cases appearing in the AD/ILR do not have a title as such in their original version (e.g. in jurisdictions where the practice is to use case numbers rather than titles). There are other circumstances (e.g. ICJ cases) where to include the full formal title (including the introductory ‘Case concerning’) would be misleading in an alphabetical table. Such cases are listed under the key element[s] (e.g. ‘Aerial Incident of 27 July 1955’ rather than ‘Case concerning ...’). The full formal titles are used, where they exist, in the table of cases by jurisdiction. ILR practice, in the presentation of cases and in the treatment of cases referred to and in the matter of cross-references, has varied considerably over the years. So far as practicable, the current table brings earlier tables into conformity with current practice. Page references in earlier tables have accordingly been deleted where they contained no more than a cross- reference or a direction to another part of the volume where treatment of the case could be found. Where, in the Annual Digest in particular, a long extract from a case has been included, this has been treated as a full report rather than a note – ‘long’, of course, being a variable concept. Current ILR practice is, wherever appropriate, to use English in case titles (e.g. -

A Music Book for Mary Tudor, Queen of France

A MUSIC BOOK FOR MARY TUDOR, QUEEN OF FRANCE Item Type Article Authors Brobeck, John T. Citation A MUSIC BOOK FOR MARY TUDOR, QUEEN OF FRANCE 2016, 35:1 Early Music History DOI 10.1017/S0261127916000024 Publisher Cambridge University Press Journal Early Music History Rights © Cambridge University Press 2016. Download date 24/09/2021 21:57:16 Item License http://rightsstatements.org/vocab/InC/1.0/ Version Final accepted manuscript Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/621897 Brobeck - 1 <special sorts: {#} (space); flat sign ({fl} in file); sharp sign ({sh} in file); natural sign ({na} in file); double flat sign ({2fl} in file [these flats are close together, not spaced]); mensuration sign cut-C ({C/} in file; see pdf> <running heads: John T. Brobeck | A Music Book for Mary Tudor, Queen of France> Early Music History (2016) Volume 35. © Cambridge University Press doi: 10.1017/S0261127916000024 JOHN T. BROBECK Email: [email protected] _________________________________________________________________________________________ A MUSIC BOOK FOR MARY TUDOR, QUEEN OF FRANCE Frank Dobbins in memoriam In 1976 Louise Litterick proposed that Cambridge, Magdalene College, Pepys Library MS 1760 was originally prepared for Louis XII and Anne of Brittany of France but was gifted to Henry VIII of England in 1509. That the manuscript actually was prepared as a wedding gift from Louis to his third wife Mary Tudor in 1514, however, is indicated by its decorative and textual imagery, which mirrors the decoration of a book of hours given by Louis to Mary and the textual imagery used in her four royal entries. Analysis of the manuscript’s tabula and texts suggests that MS 1760 was planned by Louis’s chapelmaster Hilaire Bernonneau (d. -

Anllech an Aolt an Boer an C an Cash an Caskey An

BUSCAPRONTA www.buscapronta.com ARQUIVO 08 DE PESQUISAS GENEALÓGICAS 61 PÁGINAS – MÉDIA DE 19.600 SOBRENOMES/OCORRÊNCIA Para pesquisar, utilize a ferramenta EDITAR/LOCALIZAR do WORD. A cada vez que você clicar ENTER e aparecer o sobrenome pesquisado GRIFADO (FUNDO PRETO) corresponderá um endereço Internet correspondente que foi pesquisado por nossa equipe. Ao solicitar seus endereços de acesso Internet, informe o SOBRENOME PESQUISADO, o número do ARQUIVO BUSCAPRONTA DIV ou BUSCAPRONTA GEN correspondente e o número de vezes em que encontrou o SOBRENOME PESQUISADO. Número eventualmente existente à direita do sobrenome (e na mesma linha) indica número de pessoas com aquele sobrenome cujas informações genealógicas são apresentadas. O valor de cada endereço Internet solicitado está em nosso site www.buscapronta.com . Para dados especificamente de registros gerais pesquise nos arquivos BUSCAPRONTA DIV. ATENÇÃO: Quando pesquisar em nossos arquivos, ao digitar o sobrenome procurado, faça- o, sempre que julgar necessário, COM E SEM os acentos agudo, grave, circunflexo, crase, til e trema. Sobrenomes com (ç) cedilha, digite também somente com (c) ou com dois esses (ss). Sobrenomes com dois esses (ss), digite com somente um esse (s) e com (ç). (ZZ) digite, também (Z) e vice-versa. (LL) digite, também (L) e vice-versa. Van Wolfgang – pesquise Wolfgang (faça o mesmo com outros complementos: Van der, De la etc) Sobrenomes compostos ( Mendes Caldeira) pesquise separadamente: MENDES e depois CALDEIRA. Tendo dificuldade com caracter Ø HAMMERSHØY – pesquise HAMMERSH HØJBJERG – pesquise JBJERG BUSCAPRONTA não reproduz dados genealógicos das pessoas, sendo necessário acessar os documentos Internet correspondentes para obter tais dados e informações. DESEJAMOS PLENO SUCESSO EM SUA PESQUISA. -

September 22,1921

The Republican Journal. 77 V()U ME 93. NO. 38.___BELFAST, MAINE, THURSDAY, SEPTEMBER 22. 1921. FIVE CENTS fhe and leola lucey Monroe Fair and Races. Plans tor Church Federation. They shall elect a Clem Treasurer, Hazeltine Post Activites. appoint such sub-committees and other PERSONAL PERSONAL officers as they see fit, and prescribe their — Lucey, well-known soprano two The annual of Frank Leola j Large-crowds from Belfast attended the For several years plans for uniting powers and duties. meeting Durham Miss Sara I'iSS 0f Broadway’s most popular Edith West ia spending a few Miss Effie Bridges of Boston has e three of churches Hazeltine American of been be heard in an days Monroe fair and or more of the various city VI. Post, Legion Hon- days in Boston. ..,cra stars, will races, ARTICLE the guest of her waa held brother, Sumner Bridges. > at the Colonial when fully 6,000 have ifnd later abandon- or, last Friday evening in its ’,-uncert Theatre, ! people were on the been attempted The regular Sunday morning service Miss Abbie E. Poor is visiting rela- at 8.30 m. room in the Miss Hattie Maddocks has returned to [sV'ie QCt. 7th, p. Assisting grounds. It was Monroe’s 53rd annual ed. For the paBt three weeks the matter and Sunday School shall be held in the Marsh building. There was tives in Waldoboro. on this occasion will be Adri- and seats therein her home in P^-eey event. The exhibits were the of the First Parish (Unitar- Unitarian Church, a large attendance and the following offi- Lawrence, Mass., after a 1 of the largest for federating Fred Waldo went to Bos- ae, violinist, pupil great shall be free. -

Pre-Text Text Context

PRE-TEXT TEXT CONTEXT Essays on Nineteenth-Century French Literature Edited by Robert L. Mitchell OHIO STATE UNIVERSITY PRESS : COLUMBUS Copyright © 1980 by the Ohio State University Press All Rights Reserved Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Main entry under title: Pre-text, text, context. Includes index. 1. French literature—19th century—History and criticism—Addresses, essays, lectures. I. Mitchell, Robert L., 1944- PQ282.P87 840'.9 80-11801 ISBN 0-8142-0305-1 CONTENTS Preface ix Editor's Note xi PART ONE : PRE-TEXT SUZANNE NASH Transfiguring Disfiguration in L'Homme qui rit: A Study of Hugo's Use of the Grotesque 3 BETTINA L. KNAPP La Fee aux miettes: An Alchemical Hieros Gamos 15 WILL L. McLENDON The Grotesque in Jean Lorrain's New Byzantium: Le Vice errant 25 CATHERINE LOWE The Roman tragique and the Discourse of Nervalian Mad ness 37 ANDREW J. McKENNA Baudelaire and Nietzsche: Squaring the Circle of Madness 53 NANCY K. MILLER "Tristes Triangles": Le Lys dans la vallee and Its Intertext 67 GODELIEVE MERCKEN-SPAAS Death and the Romantic Heroine: Chateaubriand and de Stael 79 vi Contents MARTHA N. MOSS Don Juan and His Fallen Angel: Images of Women in the Literature of the 1830s 89 PART TWO : TEXT ALBERT SONNENFELD Ruminations on Stendhal's Epigraphs 99 PAULINE WAHL Stendhal's Lamiel: Observations on Pygmalionism 113 ENID RHODES PESCHEL Love, the Intoxicating Mirage: Baudelaire's Quest for Com munion in "Le Vin des amants," "La Chevelure," and "Har monie du soir" 121 NATHANIEL WING The Danaides' Vessel: On Reading Baudelaire's Allegories 135 ROSS CHAMBERS Seeing and Saying in Baudelaire's "Les Aveugles" 147 LAURENCE M. -

Conroe Warrant Listing Municipal Court Current As of 01/25/2019

Conroe Warrant Listing Municipal Court Current as of 01/25/2019 Name Warrant # Amount Due DUSHA III, ALAN BRUCE MICHAEL 174416831 SPEEDING 62 MPH in a 50 MPH Zone $105.00 # Of Warrants: 1 Amount Due: $105.00 ABADALLAH, KAWAR SAMI 15030077 CAMPING IN PUBLIC OR PRIVATE AREAS PROHIBITED $416.00 15030077W FAIL TO APPEAR $416.00 # Of Warrants: 2 Amount Due: $832.00 ABARCA, ALLAN OSMAN 174804441 SPEEDING 57 MPH in a 45 MPH Zone $278.10 174804442 NO DRIVERS LICENSE $300.00 17480444W1 VIOLATE PROMISE TO APPEAR $383.00 # Of Warrants: 3 Amount Due: $961.10 ABBOTT, DARRELL EVERETTE 175606151 FAIL TO RESTRAIN YOUNGER THAN 8 OR LESSTHAN 4'9"-DRIVER $302.00 17560615W1 VIOLATE PROMISE TO APPEAR $383.00 # Of Warrants: 2 Amount Due: $685.00 ABBOTT, MICHAEL RAY 12320453 SPEEDING 64 MPH in a 45 MPH Zone $449.93 12320453 FMFR 2ND OFFENSE $690.30 12320453 DRIVING WHILE LICENSE INVALID $452.40 12320453W VIOLATE PROMISE TO APPEAR $495.30 # Of Warrants: 4 Amount Due: $2,087.93 ABBOTT, TIMOTHY MARK 12480555 POSSESSION OF DRUG PARAPHERNALIA $413.40 12480555W FAIL TO APPEAR $452.40 # Of Warrants: 2 Amount Due: $865.80 ABBOTT, WALTER FLETCHER 11450358 EXPIRED LICENSE PLATE $354.90 11450358W VIOLATE PROMISE TO APPEAR $495.30 # Of Warrants: 2 Amount Due: $850.20 ABBOTT, ZACHARY ATOM 179503061 DRIVING WHILE LICENSE INVALID $350.00 17950306W1 VIOLATE PROMISE TO APPEAR $383.00 # Of Warrants: 2 Amount Due: $733.00 ABBS, CHRISTOPHER DEMONTROND RAY 3482631 CROSS ROAD OUTSIDE CROSSWALK $213.00 348263W1 VIOLATE PROMISE TO APPEAR $497.90 # Of Warrants: 2 Amount Due: $710.90