EMBARKATIONS (OR, BOATING for BEGINNERS): a NOVEL By

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2017-2018 Designated Early College High Schools Updated 4.26.17

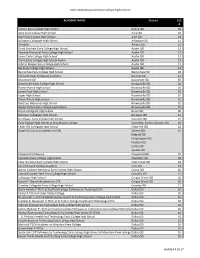

2017-2018 Designated Early College High Schools ACADEMY NAME District ESC # Victory Early College High School Aldine ISD 04 Alice Early College High School Alice ISD 02 Alief Early College High School Alief ISD 04 Arlington Collegiate High School Arlington ISD 11 Pinnacle Athens ISD 10 David Crockett Early College High School Austin ISD 13 Eastside Memorial Early College High School Austin ISD 13 Lanier Early College High School Austin ISD 13 Travis Early College High School Austin Austin ISD 13 John H. Reagan Early College High School Austin ISD 13 LBJ Early College High School Austin ISD 13 Balmorhea Early College High School Balmorhea ISD 18 Colorado River Collegiate Academy Bastrop ISD 13 Beaumont ISD Beaumont ISD 05 Brownsville Early College High School Brownsville ISD 01 Homer Hanna High School Brownsville ISD 01 James Pace High School Brownsville ISD 01 Lopez High School Brownsville ISD 01 Simon Rivera High School Brownsville ISD 01 Veterans Memorial High School Brownsville ISD 01 Gladys Porter Early College High School Brownsville ISD 01 Bryan Collegiate High School Bryan ISD 06 Burleson Collegiate High School Burleson ISD 11 Northwest Early College High School Canutillo ISD 19 Early College High School at Brookhaven College Carrollton-Farmers Branch ISD 10 Cedar Hill Collegiate High School Cedar Hill ISD 10 Angelina County Cooperative ECHS Central ISD 07 Diabold ISD Hungtington ISD Hudson ISD Lufkin ISD Zavalla ISD Chapel Hill Collegiate Chapel Hill ISD 07 Charlotte Early College High School Charlotte ISD 20 Clear Horizons Early College High School Clear Creek ISD 04 Clint ISD Early College Academy Clint ISD 19 Alamo Colleges-Memorial Early College High School Comal ISD 20 Connally Career Tech Early College High School Connally ISD 12 Collegiate High School Corpus Christi ISD 02 Harold T. -

Proceedings First Annual Palo Alto Conference

PROCEEDINGS OF THE FIRST ANNUAL PALO ALTO CONFERENCE An International Conference on the Mexican-American War and its Causes and Consequences with Participants from Mexico and the United States. Brownsville, Texas, May 6-9, 1993 Palo Alto Battlefield National Historic Site Southwest Region National Park Service I Cover Illustration: "Plan of the Country to the North East of the City of Matamoros, 1846" in Albert I C. Ramsey, trans., The Other Side: Or, Notes for the History of the War Between Mexico and the I United States (New York: John Wiley, 1850). 1i L9 37 PROCEEDINGS OF THE FIRST ANNUAL PALO ALTO CONFERENCE Edited by Aaron P. Mahr Yafiez National Park Service Palo Alto Battlefield National Historic Site P.O. Box 1832 Brownsville, Texas 78522 United States Department of the Interior 1994 In order to meet the challenges of the future, human understanding, cooperation, and respect must transcend aggression. We cannot learn from the future, we can only learn from the past and the present. I feel the proceedings of this conference illustrate that a step has been taken in the right direction. John E. Cook Regional Director Southwest Region National Park Service TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction. A.N. Zavaleta vii General Mariano Arista at the Battle of Palo Alto, Texas, 1846: Military Realist or Failure? Joseph P. Sanchez 1 A Fanatical Patriot With Good Intentions: Reflections on the Activities of Valentin GOmez Farfas During the Mexican-American War. Pedro Santoni 19 El contexto mexicano: angulo desconocido de la guerra. Josefina Zoraida Vazquez 29 Could the Mexican-American War Have Been Avoided? Miguel Soto 35 Confederate Imperial Designs on Northwestern Mexico. -

Brownsville Navigation District Of

FRIDAY, OCTOBER 9, 2020 | THE BROWNSVILLE HERALD | A7 BROWNSVILLE NAVIGATION DISTRICT OF For Early Voting, a voter may vote at any of the locations listed below: CAMERON COUNTY, TEXAS (Para Votación Adelantada, los votantes podrán votar en cualquiera de las (EL DISTRITO DE NAVEGACION DE BROWNSVILLE DEL CONDADO ubicaciones nombradas abajo) DE CAMERON, TEXAS) Locations for Early Voting Polling Places Dates and Hours of Operation (Ubicación de casillas electorales de votación (Dias y Horas Hábiles) SECOND AMENDED NOTICE OF GENERAL ELECTION adelantada) (SEGUNDO AVISO DE ELECCION GENERAL ENMENDADO) Tuesday, October 13 through Friday, October 16 9:00 AM to 7:00 PM Cameron County 954 E. Harrison Saturday, October 17 and Sunday, October 18 10:00 AM to 5:00 PM Courthouse Monday, October 19 through Friday, October 23 9:00 AM to 7:00 PM To the registered voters of the Brownsville Navigation District of Cameron County, Brownsville, TX Judicial Complex Saturday, October 24 and Sunday, October 25 10:00 AM to 5:00 PM Texas: Monday, October 26 through Friday, October 30 8:00 AM to 8:00 PM (A los votantes registrados del Distrito de Navegación de Brownsville del Condado Tuesday, October 13 through Friday, October 16 9:00 AM to 7:00 PM de Cameron, Texas Brownsville Saturday, October 17 and Sunday, October 18 10:00 AM to 5:00 PM 1000 Foust Rd. Navigation District Monday, October 19 through Friday, October 23 9:00 AM to 7:00 PM Brownsville, TX Saturday, October 24 and Sunday, October 25 10:00 AM to 5:00 PM Notice is hereby given that the polling places listed below will be open from 7:00 Board Room Monday, October 26 through Wednesday, October 28 9:00 AM to 7:00 PM a.m. -

Packet of 1St Place Essays

Embracing Culture Through the Universal Language of Mankind “Music is a moral law. It gives soul to the universe, wings to the mind, flight to the imagination, and charm and gaiety to life, and to everything.” These are the words of Plato, and despite being spoken centuries ago, the remarkable and universal truth that can be found in them has far from dwindled over time. Traces of this truth can be found today through the actions of a few exclusive and outstanding individuals, such as the highly esteemed Ms. Martha Placeres of Brownsville, Texas, a remarkable individual who has been able to effectively integrate and blend culture in a way that highlights its importance through the gift of music. Born in Puebla-Mexico, Placeres spent the first twenty years of her life surrounded by music, even at a very young age. "I guess everything started with my grandfather,” Placeres said. “He was a professional opera singer in Mexico City." Fausto de Andrés y Aguirre was always surrounded by Mexican composers as an opera singer, and was given the task of rescuing the ailing Puebla State Conservatory of Music. As a result of his hard work and dedication, the school began offering degrees. “He passed his love of music on to his 12 children," Placeres said. “He made sure that every single one of his sons and daughters could learn a little bit of music so they could understand his job…Growing up, it was just a part of my childhood” (Montoya). Her father, the late Alfonzo Placeres was a pianist, and as is her mother, Martha Aguirre, who is currently an academic director at the Puebla State Conservatory. -

Downtown Festival Drew out Music Lovers

1973 Years 382011 VOL. 38, No. 18 SERVING ANTHONY, VINTON, CANUTILLO, EAST MONTANA, HORIZON, SOCORRO, CLINT, FABENS, SAN ELIZARIO AND TORNILLO MAY 5, 2011 NEWSBRIEFS Chili cook-off On May 7th, from 10:00 am to 2:00 pm, the Horizon City Texas Chili Appreciation Society International (CASI), will be hosting a Chili Cook-off at the American Legion Post 598 on 13000 Horizon Blvd. Entry fee for those who wish to register and compete is $20.00 payable to “Pod of the Pass”. Come taste the goodness of the Southwest. Entry fee for tasters is $300 at the gate. Plenty of parking with dry camping available. Contact info: Carol Straughan at 915 852-3599 or cell 915 491-2766, email [email protected] and Thomas Cavazos at 915 564-1332, email [email protected]. Luncheon The Southwest Character Council – Photo by Alfredo Vasquez Monthly Luncheon will be Wednesday, ROCK ON – The Neon Desert Music Festival, the first of its kind in El Paso, attracted about 11,000 music lovers. Neon Desert Festival May 11 from 11:45 a.m. – 1:00 p.m. at was the brainchild of festival organizers, Zach Paul, Gina Martinez and Brian Chavez. Above a crowd gathers in front of one of the Great American Land & Cattle Company, performance stages to hear one of the 29 bands that perform during the 12-hour event. 701 S. Mesa Hills, El Paso. The character quality for May is Discernment. The cost is $10 per person for lunch, networking and training. RSVP to (915) 779-3551 to Downtown festival drew out music lovers reserve your spot, and make sure enough promise of an array of musicians is what that is missing here when compared to those By Alfredo Vasquez meals are prepared. -

2021 Finalist Directory

2021 Finalist Directory April 29, 2021 ANIMAL SCIENCES ANIM001 Shrimply Clean: Effects of Mussels and Prawn on Water Quality https://projectboard.world/isef/project/51706 Trinity Skaggs, 11th; Wildwood High School, Wildwood, FL ANIM003 Investigation on High Twinning Rates in Cattle Using Sanger Sequencing https://projectboard.world/isef/project/51833 Lilly Figueroa, 10th; Mancos High School, Mancos, CO ANIM004 Utilization of Mechanically Simulated Kangaroo Care as a Novel Homeostatic Method to Treat Mice Carrying a Remutation of the Ppp1r13l Gene as a Model for Humans with Cardiomyopathy https://projectboard.world/isef/project/51789 Nathan Foo, 12th; West Shore Junior/Senior High School, Melbourne, FL ANIM005T Behavior Study and Development of Artificial Nest for Nurturing Assassin Bugs (Sycanus indagator Stal.) Beneficial in Biological Pest Control https://projectboard.world/isef/project/51803 Nonthaporn Srikha, 10th; Natthida Benjapiyaporn, 11th; Pattarapoom Tubtim, 12th; The Demonstration School of Khon Kaen University (Modindaeng), Muang Khonkaen, Khonkaen, Thailand ANIM006 The Survival of the Fairy: An In-Depth Survey into the Behavior and Life Cycle of the Sand Fairy Cicada, Year 3 https://projectboard.world/isef/project/51630 Antonio Rajaratnam, 12th; Redeemer Baptist School, North Parramatta, NSW, Australia ANIM007 Novel Geotaxic Data Show Botanical Therapeutics Slow Parkinson’s Disease in A53T and ParkinKO Models https://projectboard.world/isef/project/51887 Kristi Biswas, 10th; Paxon School for Advanced Studies, Jacksonville, -

Appendices to the Reporting and Procedures

APPENDICES to the REPORTING and PROCEDURES MANUALS for Texas Universities, Health-Related Institutions, Community, Technical, and State Colleges, and Career Schools and Colleges Fall 2007 TEXAS HIGHER EDUCATION COORDINATING BOARD Educational Data Center TEXAS HIGHER EDUCATION COORDINATING BOARD APPENDICES TEXAS UNIVERSITIES, HEALTH-RELATED INSTITUTIONS, COMMUNITY, TECHNICAL, AND STATE COLLEGES, AND CAREER SCHOOLS Revised Fall 2007 For More Information Please Contact: Doug Parker Educational Data Center Texas Higher Education Coordinating Board P.O. Box 12788 Austin, Texas 78711 (512) 427-6287 FAX (512) 427-6447 [email protected] The Texas Higher Education Coordinating Board does not discriminate on the basis of race, color, national origin, gender, religion, age or disability in employment or the provision of services. TABLE OF CONTENTS A. Institutional Code Numbers for Texas Institutions Page Public Universities ...................................................................................................... A.1 Independent Senior Colleges and Universities .......................................................... A.2 Public Community, Technical, and State Colleges .................................................... A.3 Independent Junior Colleges ..................................................................................... A.5 Texas A&M University System Service Agencies ...................................................... A.5 Health-Related Institutions ........................................................................................ -

Subject to Change November 3, 2020

GENERAL ELECTION LIST OF POLLING PLACES SUBJECT TO CHANGE NOVEMBER 3, 2020 PCT. SITE ADDRESS CITY 1, 83 Port Isabel City Hall 305 E. Maxan St. Port Isabel 2, 99 Las Yescas Elementary School 23413 FM 803 Las Yescas 3 Los Fresnos Community Center 204 N. Brazil St. Los Fresnos 4, 105 Villareal Elementary School 7770 E. Lakeside Blvd. Olmito 5, 37 J.T. Canales Elementary School 1811 International Blvd. Brownsville 6, 7, 8, 9 Cameron County Courthouse Judicial Complex 954 E. Harrison St. Brownsville 10 Cromack Elementary School 3200 E. 30th St. Brownsville 11 Skinner Elementary School 411 W. St. Charles St. Brownsville 12 Russell Elementary School 800 Lakeside Blvd. Brownsville 13 Central Administration Building 708 Palm Blvd. Brownsville 14, 108 Bob Clark Social Service Center 9901 California Rd. Brownsville 15 R.L. Martin Elementary School 1701 Stanford St. Brownsville 16 Villa Nueva Elementary School 7455 Old Military Road Brownsville 17 La Encantada Elementary School 35001 FM 1577 San Benito 18 San Benito Fire Station 1205 S. Sam Houston San Benito 19 San Benito Community Bldg. 210 E. Heywood St. San Benito 20 Rio Hondo Civic Center 121 N. Arroyo St. Rio Hondo 21 Frank Roberts Elementary School 451 Biddle St. San Benito 22 Sullivan Elementary School 900 Elizabeth St. San Benito 23, 43, 103 Bonita Park Community Bldg. 601 S. Rangerville Rd. Harlingen 24 Santa Maria ISD Administrative Bldg. Board Room 11119 Military Hwy 281 Santa Maria 25 Los Indios Community Center 309 E. Heywood St. Los Indios 26, 55 American Legion Hall 219 E. Commercial Ave. La Feria 27 Maria Luisa Ruiz Guerra County Annex Bldg. -

VITA SITES 2016 Free Tax Assistance for Individuals and Families Earning $53,000 Or Less

VITA SITES 2016 Free Tax Assistance For Individuals and Families earning $53,000 or less BOYS & GIRLS CLUB OF LAGUNA MADRE ETHEL L. WHIPPLE MEMORIAL LIBRARY 190 Port Rd. Port Isabel, TX 78578 402 W. Ocean Blvd. Los Fresnos, 78566 January 27 - March 2 January 18 - March 10 Wednesday: 5:00 pm- 7:00 pm Thursday: 5:30 pm-8:30 pm No appointment necessary *Appointment Only Call (956) 233-5330 BROWNSVILLE PUBLIC UTILITIES BOARD GLADYS PORTER HIGH SCHOOL 1425 Robin Hood Drive Brownsville, 78521 3500 International Blvd. Brownsville, TX 78521 January 28 - February 23 February 1-23; April 8; April 9 (Closed February 16) Monday: 4:00 pm -6:00 pm Tuesday: 5:30 pm- 8:00 pm Tuesday: 4:00 pm - 6:00 pm Thursday: 5:30 pm- 8:00 pm Thursday: 4:00 pm -6:00 pm No appointment necessary Friday (4/8) 9:00 am-4:00 pm Saturday(4/9) 9:00 am-12:00 pm COMMUNITY DEVELOPMENT CORP. OF No appointment necessary BROWNSVILLE (CDCB) HARLINGEN OUTREACH CENTER (HOC) 901 East Levee St. Brownsville, 78520 1102 S. Commerce St. Harlingen, TX 78550 January 25 - April 14 January 22 - March 18 (Closed February 15, 25 and March 28) (Closed February 15) Monday: 6:00 pm- 8:00 pm Monday: 4:00 pm- 8:00 pm Wednesday: 9:00 am- 5:00 pm; 6:00 pm-8:00 pm Wednesday: 4:00 pm- 8:00 pm Thursday: 6:00 pm- 8:00 pm Friday: 4:00 pm- 8:00 pm *Appointments only on Wednesdays 9:00 am- 5:00 pm No appointment necessary Call (956) 541-4955 VITA SITES 2016 Free Tax Assistance For Individuals and Families earning $53,000 or less HOMER HANNA HIGH SCHOOL LOPEZ HIGH SCHOOL 2615 Price Road Brownsville, TX 78521 3205 S Dakota Ave. -

Many Stars Come from Texas

MANY STARS COME FROM TEXAS. t h e T erry fo un d atio n MESSAGE FROM THE FOUNDER he Terry Foundation is nearing its sixteenth anniversary and what began modestly in 1986 is now the largest Tprivate source of scholarships for University of Texas and Texas A&M University. This April, the universities selected 350 outstanding Texas high school seniors as interview finalists for Terry Scholarships. After the interviews were completed, a record 165 new 2002 Terry Scholars were named. We are indebted to the 57 Scholar Alumni who joined the members of our Board of Directors in serving on eleven interview panels to select the new Scholars. These freshmen Scholars will join their fellow upperclass Scholars next fall in College Station and Austin as part of a total anticipated 550 Scholars: the largest group of Terry Scholars ever enrolled at one time. The spring of 2002 also brought graduation to 71 Terry Scholars, many of whom graduated with honors and are moving on to further their education in graduate studies or Howard L. Terry join the workforce. We also mark 2002 by paying tribute to one of the Foundations most dedicated advocates. Coach Darrell K. Royal retired from the Foundation board after fourteen years of outstanding leadership and service. A friend for many years, Darrell was instrumental in the formation of the Terry Foundation and served on the Board of Directors since its inception. We will miss his seasoned wisdom, his keen wit, and his discerning ability to judge character: all traits that contributed to his success as a coach and recruiter and helped him guide the University of Texas football team to three national championships. -

THECB Appendices 2011

APPENDICES to the REPORTING and PROCEDURES MANUALS for Texas Universities, Health-Related Institutions, Community, Technical, and State Colleges, and Career Schools and Colleges Summer 2011 TEXAS HIGHER EDUCATION COORDINATING BOARD Educational Data Center TEXAS HIGHER EDUCATION COORDINATING BOARD APPENDICES TEXAS UNIVERSITIES, HEALTH-RELATED INSTITUTIONS, COMMUNITY, TECHNICAL, AND STATE COLLEGES, AND CAREER SCHOOLS Revised Summer 2011 For More Information Please Contact: Doug Parker Educational Data Center Texas Higher Education Coordinating Board P.O. Box 12788 Austin, Texas 78711 (512) 427-6287 FAX (512) 427-6147 [email protected] The Texas Higher Education Coordinating Board does not discriminate on the basis of race, color, national origin, gender, religion, age or disability in employment or the provision of services. TABLE OF CONTENTS A. Institutional Code Numbers for Texas Institutions Page Public Universities .................................................................................................................... A.1 Independent Senior Colleges and Universities ........................................................................ A.2 Public Community, Technical, and State Colleges................................................................... A.3 Independent Junior Colleges .................................................................................................... A.5 Texas A&M University System Service Agencies .................................................................... A.5 Health-Related -

PRECINCT LOCATION ADDRESS CITY Republican Primary Election

Republican Primary Election (Elección Primaria del Partido Republicano) March 4, 2014 Cameron County, Texas (El 4 de Marzo del 2014 es el Día de Elección en el Condado Cameron) Election Day Polls OPEN from 7:00 A.M. to 7:00 P.M. (Las Casillas Electorales Abriran de 7:00 am. a 7:00 pm) PRECINCT LOCATION ADDRESS CITY 1, 83 Bennie Ochoa III Annex Bldg. 505 Hwy 100 Port Isabel 2, 99 Las Yescas 23413 FM 803 Las Yescas 3, 65, 66 Los Fresnos Community Building 204 N. Brazil St. Los Fresnos 4, 95 Villarreal Elementary School 7700 E. Lakeside Blvd. Olmito 5, 46, 63, 76, 96, 71 Oliveira Middle School 444 Land O’Lakes Dr. Brownsville 6, 7, 8, 9, 37, 45, 70 J.T. Canales Elementary School 1811 International Blvd. Brownsville 10, 53, 60, 69, 77 Palm Grove Elementary School 7942 Southmost Rd. Brownsville 11, 13, 15, 38, 97 Sharp Elementary School 1439 Palm Blvd. Brownsville 12, 47, 49, 62, 75 James Pace High School 314 W. Los Ebanos Blvd Brownsville 14, 68, 82, 86,102, 108 Rivera High School 6955 FM 802 Brownsville 16, 48, 98, 107 Benavidez Elementary School 3101 McAllen Road Brownsville 17, 25, 51 La Paloma School 35076 Main Street San Benito 18,19, 50, 109 Ed Downs Elementary School 1302 N. Dick Dowling San Benito 20, 81 Rio Hondo High School 22547 State Hwy 345 Rio Hondo 21, 22, 40 Fred Booth School 705 Zaragoza St. San Benito 23, 43 Community Bldg Bonita Park 601 S. Rangerville Rd Harlingen 24, 26 Green Bay South Mobile Park White Ranch Road La Feria 27 Santa Rosa High School 102 S.