The Approach of the Omora Ethnobotanical Park

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chapter14.Pdf

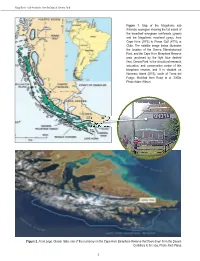

PART I • Omora Park Long-Term Ornithological Research Program THE OMORA PARK LONG-TERM ORNITHOLOGICAL RESEARCH PROGRAM: 1 STUDY SITES AND METHODS RICARDO ROZZI, JAIME E. JIMÉNEZ, FRANCISCA MASSARDO, JUAN CARLOS TORRES-MURA, AND RAJAN RIJAL In January 2000, we initiated a Long-term Ornithological Research Program at Omora Ethnobotanical Park in the world's southernmost forests: the sub-Antarctic forests of the Cape Horn Biosphere Reserve. In this chapter, we first present some key climatic, geographical, and ecological attributes of the Magellanic sub-Antarctic ecoregion compared to subpolar regions of the Northern Hemisphere. We then describe the study sites at Omora Park and other locations on Navarino Island and in the Cape Horn Biosphere Reserve. Finally, we describe the methods, including censuses, and present data for each of the bird species caught in mist nets during the first eleven years (January 2000 to December 2010) of the Omora Park Long-Term Ornithological Research Program. THE MAGELLANIC SUB-ANTARCTIC ECOREGION The contrast between the southwestern end of South America and the subpolar zone of the Northern Hemisphere allows us to more clearly distinguish and appreciate the peculiarities of an ecoregion that until recently remained invisible to the world of science and also for the political administration of Chile. So much so, that this austral region lacked a proper name, and it was generally subsumed under the generic name of Patagonia. For this reason, to distinguish it from Patagonia and from sub-Arctic regions, in the early 2000s we coined the name “Magellanic sub-Antarctic ecoregion” (Rozzi 2002). The Magellanic sub-Antarctic ecoregion extends along the southwestern margin of South America between the Gulf of Penas (47ºS) and Horn Island (56ºS) (Figure 1). -

Directing Approaches from Contemporary Chilean Women

EXPANDING THEATRE: DIRECTING APPROACHES FROM CONTEMPORARY CHILEAN WOMEN DIRECTORS A THESIS IN Theatre Presented to the Faculty of the University of Missouri-Kansas City in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree MASTER OF ARTS by MARY ALLISON JOSEPH B.A., University of South Carolina, 2009 Kansas City, Missouri 2020 © 2020 MARY ALLISON JOSEPH ALL RIGHTS RESERVED EXPANDING THEATRE: DIRECTING APPROACHES FROM CONTEMPORARY CHILEAN WOMEN DIRECTORS Mary Allison Joseph, Candidate for the Master of Arts Degree University of Missouri-Kansas City, 2020 ABSTRACT This thesis examines the careers, theatrical ideologies, and directing methodologies of three contemporary Chilean women stage directors: Andrea Giadach, Alexandra von Hummel, and Ignacia González. Respective chapters provide an overview of each director’s career that includes mention of formative moments. Each chapter also includes a synthesis of the director’s thinking as distilled from personal interviews and theoretical works, followed by a methodological case study that allows for analysis of specific directing methods, thus illuminating the director’s beliefs in action. In each chapter, the author asserts that the director’s innovative thinking and creative practices constitute expansions of the theatrical artform. Finally, the author traces similarities across the directing approaches of the three directors, which suggest guiding ideas for expanding the theatrical artform. Chapter one explores the directing career of Andrea Giadach, with highlights including her acting experiences in La lluvia de verano (2005) and Mateluna (2012) and her iii directing projects Mi mundo patria (2008) and Penélope ya no espera (2014). Her beliefs about political theatre are illuminated through a directing case study of her 2019 production of El Círculo. -

Chilean-Navy-Day-2016-Service.Pdf

Westminster Abbey A W REATHLAYING CEREMONY AT THE GRAVE OF ADMIRAL LORD COCHRANE , TH 10 EARL OF DUNDONALD ON CHILEAN NAVY DAY Thursday 19th May 2016 11.00 am THE CHILEAN NAVY Today we honour those men and women who, over the centuries, have given their lives in defence of their country, and who, through doing so, have shown the world their courage and self-sacrifice. As a maritime country, Chile has important interests in trade and preventing the exploitation of fishing and other marine resources. The Chilean economy is heavily dependent on exports that reach the world markets through maritime transport. This is reflected by the fact that Chile is the third heaviest user of the Panama Canal. Ninety percent of its foreign trade is carried out by sea, accounting for almost fifty-five percent of its gross domestic product. The sea is vital for Chile’s economy, and the Navy exists to protect the country and serve its interests. Each year, on 21 st May, all the cities and towns throughout Chile celebrate the heroic deeds of Commander Arturo Prat and his men. On that day in 1879, Commander Arturo Prat was commanding the Esmeralda, a small wooden corvette built twenty-five years earlier in a Thames dockyard. With a sister vessel of lighter construction, the gunboat Covadonga, the Esmeralda had been left to blockade Iquique Harbour while the main fleet had been dispatched to other missions. They were confronted by two Peruvian warships, the Huáscar and the Independencia. Before battle had ensued, Commander Prat had made a rousing speech to his crew where he showed leadership to motivate them to engage in combat. -

Located in Tierra Del Fuego, 20 Minutes from the National Park And

Located in Tierra del Fuego, 20 minutes from the National Park and within Cerro Alarkén Natural Reserve, Arakur Ushuaia overlooks its stunningly beautiful locale from atop an outcrop just outside the city surrounded by stunning panoramic views, native forests, and natural terraces harmoniously integrated into the environment. Arakur Ushuaia is a member of The Leading Hotels of the World and it is the only resort in the Southern Patagonia to have become part of this exclusive group of hotels. Location Arakur Ushuaia extends along a spectacular natural balcony 800 feet above sea level in the mythical province of Tierra del Fuego. Surrounded by stunning panoramic views of the city of Ushuaia and of the Beagle Channel, Arakur Ushuaia is located just 10 minutes from the city and the port of Ushuaia and 20 minutes from the international airport and the Cerro Castor Ski Resort. Located within the Cerro Alarkén Nature Reserve close to Mount Alarken’s summit amidst 250 acres of native forests of lengas, ñires and coihues, diverse species of fauna and flora, the location offers the perfect balance between calmness and adventure. Accommodations The magnificent lobby welcomes the guests with its large windows, the warmth of their fireplaces, and a sophisticated décor made with fine materials from different Argentine regions, such as craft leather and South American aromatic wood. Arakur Ushuaia was created for enjoyment of the environment, and the hotel practices and promotes wise and sustainable use of resources. Over 100 rooms and suites are decorated with custom-made solid wood furniture, craft leather and the bathrooms are appointed with Hansgrohe faucets and Duravit bathroom appliances with Starck design. -

Voyage to Patagonia and Cape Horn

English VOYAGE TO PATAGONIA AND CAPE HORN www.australis.com CHILE ARGENTINA PATAGONIA EL CALAFATE NATIONAL PARK TORRES DEL PAINE PUERTO NATALES Magdalena Island PUNTA ARENAS STRAIT OF MAGELLAN TIERRA Tuckers Islets DEL FUEGO Àguila Glacier Brookes Glacier Cóndor Glacier Ainsworth Bay USHUAÏA Porter Glacier BEAGLE CANAL Wulaia Bay Pia Glacier Glacier Alley Cape Horn Embarcation Ports A UNIQUE, UNFORGETTABLE Other points of interest in Patagonia JOURNEY TO Excursions THE END OF THE WORLD Panoramic Navigation — PATAGONIA Join us, for a one-off exploration of the natural wonders, isolated fjords and surprising wildlife of Tierra del Fuego in southernmost Patagonia. Here at Australis we have been navigating the waters of Cape Horn, the Beagle Channel and Strait of Magellan since 1990 as a leading expedition cruise company. During that time our passion and goal has never changed: to transport our guests to another world, one which is wild and beautiful, untouched by humankind and rarely seen by tourists; a unique experience that will not be forgotten. A UNIQUE, UNFORGETTABLE JOURNEY TO THE END OF THE WORLD — www.australis.com Australis cruise routes all encompass the hidden canals, fjords and environments of this evocative part of Patagonia. We have access to areas that other cruise operators do not, meaning that your on-land and offshore excursions – whether trekking towards giant glaciers, wandering forest trails or exploring the delights of the Penguin colony – will be in complete isolation. Our itineraries also include a stop at Cape Horn, the southernmost point in the Americas which is often nicknamed the ‘End of the World’. -

Fotografías De Yaganes Tomadas Por Martin Gusinde (1918-1923)

MIRADAS SOBRE EL REENCUENTRO: DOS CONTEXTOS DE DEVOLUCIÓN DE LAS FOTOGRAFÍAS DE YAGANES TOMADAS POR MARTIN GUSINDE (1918-1923) DANIELLA RAMÍREZ1 RESUMEN En el presente artículo se hace análisis de dos experiencias de devolución fotográfica a los yaganes –indígenas originarios del sur de la Patagonia-, tomadas por Martin Gusinde, antropólogo y sacerdote del Verbo Divino. El primer análisis refiere a la devolución realizada durante sus viajes al sur austral de la Patagonia chilena y argentina entre 1918 y 1923; el segundo, a la devolución efectuada entre 2012-2014, como parte del trabajo conjunto del Museo Antropológico Martin Gusinde con la comunidad indígena yagán (Puerto Williams, Chile). En este circuito de las dos devoluciones, se presupone un “reencuentro”, donde la fotografía es un medio visual que se actualiza y resignifica. En él, el archivo, el texto etnográfico y el museo son espacios que permiten identificar tránsitos de sentido de la imagen, de los que surgen tensiones entre los imaginarios sobre los yaganes, con las historias y memorias familiares y regionales. PALABRAS CLAVE Yaganes; Martin Gusinde; Fotografía etnográfica; Patagonia; Museo PICTURING THE ENCOUNTERS: TWO CONTEXTS OF RETURNING PHOTOGRAPHS OF YAGANES TOOK BY MARTIN GUSINDE(1918-1923) ABSTRACT This article analyzes two experiences of returning photographs to the yagans – an indigenous group of southern Patagonia - taken by Martin Gusinde, an anthropologist and Austrian priest. The first analysis refers to the pictures returned by Martin Gusinde during his trips to southern Chilean and Argentinean Patagonia between 1918 and 1923. The second analysis refers to the photographs that were returned between 2012-2014 as part of the joint project between the Martin Gusinde Anthropological Museum and the yagan indigenous community (Puerto Williams, Chile). -

Processes of Signification and Resignification of a City, Temuco 1881-2019

CIUDAD RESIGNIFICADA PROCESSES OF SIGNIFICATION AND RESIGNIFICATION OF A CITY, TEMUCO 1881-2019 Procesos de significación y resignificación de una ciudad, Temuco 1881-20198 Processos de significado e ressignificação de uma cidade, Temuco 1881-2019 Jaime Edgardo Flores Chávez Académico, Departamento de Ciencias Sociales e Investigador del Centro de Investigaciones Territoriales (CIT). Universidad de La Frontera. Temuco, Chile. [email protected] https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6153-2922 Dagoberto Godoy Square or the Hospital, in the background the statue of Caupolicán and the Conun Huenu hill. Source: Jaime Flores Chávez. This article was funded by the Research Directorate of the University of La Frontera, within the framework of projects DIUFRO No. DI19-0028, No. DI15-0045 and No. DI15-0026. Articulo recibido el 04/05/2020 y aceptado el 24/08/2020. https://doi.org/10.22320/07196466.2020.38.058.02 CIUDAD RESIGNIFICADA ABSTRACT The social unrest that unfolded from October 2019 on saw, among its most visible expressions, the occupation of public spaces like streets, avenues and squares. The “attack” on the monuments that some associated with a kind of rebellion against the history of Chile was also extensively recorded. These events lead us along the paths of history, memory, remembrance and oblivion, represented in monuments, official symbols, the names of streets, squares and parks around the city, and also, along interdisciplinary paths to ad- dress this complexity using diverse methodologies and sources. This article seeks to explain what happened in Temuco, the capital of the Araucanía Region, during the last few months of 2019. For this purpose, a research approach is proposed using a long-term perspective that makes it possible to find the elements that started giving a meaning to the urban space, to then explore what occurred in a short time, between October and November, in the logic of the urban space resignification process. -

Argentine and Chilean Claims to British Antarctica. - Bases Established in the South Shetlands

Keesing's Record of World Events (formerly Keesing's Contemporary Archives), Volume VI-VII, February, 1948 Argentine, Chilean, British, Page 9133 © 1931-2006 Keesing's Worldwide, LLC - All Rights Reserved. Argentine and Chilean Claims to British Antarctica. - Bases established in the South Shetlands. - Chilean President inaugurates Chilean Army Bases on Greenwich Island. - Argentine Naval Demonstration in British Antarctic Waters. - H.M.S. "Nigeria" despatched to Falklands. - British Government Statements. - Argentine-Chilean Agreement on Joint Defence of "Antarctic Rights." - The Byrd and Ronne Antarctic Expeditions. - Australian Antarctic Expedition occupies Heard Islands. The Foreign-Office in London, in statements on Feb. 7 and Feb. 13, announced that Argentina and Chile had rejected British protests, earlier presented in Buenos Aires and Santiago, against the action of those countries in establishing bases in British Antarctic territories. The announcement of Feb. 7 stated that on Dec. 7, 1947, the British Ambassador in Buenos Aires, Sir Reginald Leeper, had presented a Note expressing British "anxiety" at the activities in the Antarctic of an Argentine naval expedition which had visited part of the Falkland Islands Dependencies, including Graham Land, the South Shetlands, and the South Orkneys, and had landed at various points in British territory; that a request had been made for Argentine nationals to evacuate bases established on Deception Island and Gamma Island, in the South Shetlands; that H.M. Government had proposed that the Argentine should submit her claim to Antarctic sovereignty to the International Court of Justice for adjudication; and that on Dec. 23, 1947, a second British Note had been presented expressing surprise at continued violations of British territory and territorial waters by Argentine vessels in the Antarctic. -

Fjords of Tierra Del Fuego

One Way Route Punta Arenas - Ushuaia | 4 NIGHTS Fjords of Tierra del Fuego WWW.AUSTRALIS.COM Route Map SOUTH AMERICA Santiago Buenos Aires CHILE Punta Arenas 1 STRAIT OF MAGELLAN TIERRA DEL FUEGO 2 Tuckers Islets 2 Ainsworth Bay DARWIN RANGE Pía Glacier 3 5 Ushuaia ARGENTINA 3 BEAGLE CHANNEL Glacier Alley 4 Bahía Wulaia Day 1 : Punta Arenas Day 2 : Ainsworth Bay - Tuckers Islets* 4 Day 3 : Pía Glacier - Glacier Alley** Cape Horn Day 4 :Cape Horn - Wulaia Bay Day 5 : Ushuaia * In September and April, this excursion is replaced by a short walk to a nearby glacier at Brookes Bay. ** Not an excursion Map for tourism related purposes Day 1: Punta Arenas Check in at 1398 Costanera del Estrecho Ave. (Arturo Prat Port) between 13:00 and 17:00. Board at 18:00 (6 PM). After a welcoming toast and introduction of captain and crew, the ship departs for one of the remotest corners of planet Earth. During the night we cross the Strait of Magellan and enter the labyrinth of channels that define the southern extreme of Patagonian. The twinkling lights of Punta Arenas gradually fade into the distance as we enter the Whiteside Canal between Darwin Island and Isla Grande de Tierra del Fuego. Day 2: Ainsworth Bay & Tuckers Islets By dawn the ship is sailing up Admiralty Sound (Seno Almirantazgo), a spectacular offshoot of the Strait of Magellan that stretches nearly halfway across Tierra del Fuego. The snowcapped peaks of Karukinka Natural Park stretch along the north side of the sound, while the south shore is defined by the deep fjords and broad bays of Alberto de Agostini National Park. -

2021-22 Antarctic & Sub-Antarctic Sea Voyages Brochure

ANTARCTIC AND SUB-ANTARCTIC SEA VOYAGES 2021·22 SE ASO N The Falkland Islands (Islas Malvinas) | South Georgia | Antarctic Peninsula Exclusive Partner's Edition ANTARCTIC PENINSULA AND SOUTH SHETLAND ISLANDS SOUTH AMERICA Falkland Islands (Malvinas) CHILE Punta Arenas Port Stanley Atacama Desert (Chile) PACIFIC OCEAN Ushuaia ATLANTIC (Argentina) OCEAN Santiago Puerto Williams (Chile) South Georgia and the Cape Horn South Sandwich Islands (Chile) Puerto Montt Drake Passage SOUTH SHETLAND South Orkney Islands ISLANDS Elephant Island Torres del Paine King George Island Frei Station (Chile) Punta Arenas Fildes Bay Livingston Island Half Moon Island Hannah Point Deception Bransfield Strait Island Joinville Island O'Higgins Trinity Island Station Esperanza Brabant Island Gerlache (Chile) Strait Station Anvers Island (Argentina) ANTARCTICA Port Lockroy (UK) Paradise Bay Petermann Island Almirante Vernadsky Station Brown Station (Ukraine) (Argentina) Biscoe Island WEDDELL SEA Antarctic Polar Circle ANTARCTIC PENINSULA SUMMARY 5 Discover Antarctica and the 19 DATES & PRICES 28 PLANNING YOUR TRIP Southern Ocean 20 Dates & Prices 29 Arrival and Departure Details 6 Traveling on our Small Expedition Ships 21 Inclusions & Exclusions 30 Flight and Hotel Package 8 Our Company 31 Packing for Your Trip 22 EXPERIENCES & ADVENTURES 32 Useful Tips 9 ITINERARIES 23 The Antarctica21 Expedition 33 Important Trip Details 11 Falklands (Malvinas) & South Georgia Experience 12 Antarctica, South Georgia & 24 Sea Kayaking in Antarctica 35 TERMS & CONDITIONS The Falkland Islands 25 Hiking and Snowshoeing in Antarctica 14 Antarctic Small Ship Expedition 26 Life on Board 27 Education Program 15 VESSELS 16 Magellan Explorer 18 Ocean Nova Travel with Antarctica21 for a transformative, once-in-a-lifetime experience Hiking in Antarctica © K. -

Chile's National Interest in the Oceans Victor Ariel Gallardo University of Rhode Island

University of Rhode Island DigitalCommons@URI Theses and Major Papers Marine Affairs 1974 Chile's National Interest in the Oceans Victor Ariel Gallardo University of Rhode Island Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.uri.edu/ma_etds Part of the Oceanography and Atmospheric Sciences and Meteorology Commons Recommended Citation Gallardo, Victor Ariel, "Chile's National Interest in the Oceans" (1974). Theses and Major Papers. Paper 84. This Major Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the Marine Affairs at DigitalCommons@URI. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Major Papers by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@URI. For more information, please contact [email protected]. PD.-~fhle+-- .... Le~-,-sl c~-tIOn /;' :o-~ ::.::..::::=:-======:=:=. ~ () l i c.',,= -- -- --..- --- - rr> ( .....~ CHILE'S NATIONAL INTEREST IN THE OCEANS • by Victor Ariel Gallardo .. ---- Submitted to , The University of Rhode Island , <, .- in Partial Fulfillment of (~ the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Marine Affairs 1974 The University of Rhode Island Kingston, R. 1. U.S.A. ~ (~ ~ i.>: ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS: I wish to express my deep gratitude to the University of Rhode Island, the International Center for Marine Resource Development, and the Master of Marine Affairs Program, for the precious opportunity offered to me, by way of a fellowship and financial assistance, to broader my horizons in the affairs of the sea. To Dr. Nelson Marshall, Dr. Lewis M. Alexander, Dr. John K. GamblE and Mr. Raymond Siuta my deepest appreciation. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTE1t PAGE ACK1J'O ~II..EDGME.NTS ••••••••.•••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• i LIST OF TABLE'S •••••••••••••••••••• ••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• ii I INTRODUCTION •••• ••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• 1 II ANALYSIS OF THE NATIONAL INDICES OF MARINE INTEREST OF CHILE ••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• 10 1. -

C U R R I C U L U M V I T

C U R R I C U L U M V I T A E DATOS PERSONALES NOMBRE : Nelson Isaac Cárcamo Barrera. FECHA DE NACIMIENTO : 16 de Noviembre de 1951. CIUDAD DE ORIGEN : Punta Arenas. CEDULA DE IDENTIDAD : 06.305.413-5 ESTADO CIVIL : Casado – 2 hijos. NACIONALIDAD : Chilena. DOMICILIO : Tte. Muñoz Nº 093. FONO : 61 – 621147 (Particular). TITULO : Profesor de Educación General Básica. INSTITUCION QUE OTORGA EL TITULO : Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile, Sede Temuco, Campus Victoria. AÑO DE EGRESO : 1983. LUGAR DE TRABAJO : Liceo Municipal Donald Mc. Intyre Griffiths de Puerto Williams, Comuna Cabo de Hornos. CARGO : Jefe Técnico Pedagógico de E.M. HORAS DE CONTRATO : 44 Horas. ANTECEDENTES PROFESIONALES : Agosto - 1983. Certificado de Practica Profesional en Escuela G-217 California,de la I. Municipalidad de Victoria , IX Región de la Araucanía. Agosto-Diciembre 1984. Decreto Exento Nº 333 del 17 de Octubre de 1984, suplencia en Escuela F-98 Michigan , dependiente de la I. Municipalidad de Collipulli, IX Región de la Araucanía. Años 1985 -1987 : Decreto Nº 008 del 29 de Marzo de 1985, asume de Titular como Docente en la Escuela G – 214 de Trangol, dependiente de la I.Municipalidad Victoria. IX Región. Años 1987 -1991 : Decreto Exto. Nº 014 del 26 de Febrero de 1987, designa Director de la Escuela F -226 Quino, dependiente de la I. Municipalidad de Victoria, IX Región. Noviembre.1991 – Marzo 1992 : Oficio Nº 638 del 7 de Octubre de 1991, obtiene por Concurso Público la Dirección de la Escuela G – 43 de la Comuna de Timaukel, XII Reg. de Magallanes Antártica Chilena.