Durham E-Theses

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Christian Public Ethics Sagepub.Co.Uk/Journalspermissions.Nav Tjx.Sagepub.Com Robin Gill

Theology 0(0) 1–9 ! The Author(s) 2015 Reprints and permissions: Christian public ethics sagepub.co.uk/journalsPermissions.nav tjx.sagepub.com Robin Gill This special online issue of Theology focuses upon Christian public ethics or, more specifically, upon those forms of Christian ethics that have contributed sig- nificantly to public debate. Throughout the 95 years of the journal’s history, there has been discussion about public ethics (even if it has not always been named as such). However, Christian public ethics had a particular flourishing between 1965 and 1975, when Professor Gordon Dunstan (1918–2004) was editor. When I became editor of Theology in January 2014, I acknowledged at once my personal debt to Gordon. He encouraged and published my very first article when I was still a postgraduate in 1967, and several more articles beyond that. And, speaking personally, his example of deep engagement in medical ethics was inspirational. When he died, The Telegraph noted the following among his many achievements: He was president of the Tavistock Institute of Medical Psychology and vice-president of the London Medical Group and of the Institute of Medical Ethics. During the 1960s he was a member of a Department of Health Advisory Group on Transplant Policy, and from 1989 to 1993 he served on a Department of Health committee on the Ethics of Gene Therapy. From 1990 onwards he was a member of the Unrelated Live Transplant Regulatory Authority and from 1989 to 1993 he served on the Nuffield Council on Bioethics. (19 January 2004) The two most substantial ethical contributions that I have discovered in searching through back issues of Theology were both published when he was editor and were doubtless directly encouraged by him. -

Markham 2019 CV

1 CURRICULUM VITAE The Very Rev Ian S. Markham, Ph.D. Dean and President Virginia Theological Seminary 3737 Seminary Road Alexandria, VA 22304 CONTACT INFORMATION: EMAIL: [email protected] TELEPHONE: (703) 461 1701 DATE OF BIRTH: 9/19/62 MARITAL STATUS: Lesley 1987 STATUS: American Citizen ORDINATION: June 9 2007 (as Deacon in the Episcopal Church), December 11, 2007 (as Priest in the Episcopal Church) ACADEMIC QUALIFICATIONS: Ph.D. in Christian Ethics - University of Exeter (1995) M.Litt. in Philosophy and Ethics - University of Cambridge (1986-1989) B.D. in Theology - University of London (1982-1985) APPOINTMENTS: August 2007 to Present: Dean and President of Virginia Theological Seminary August 2001 to 2007: Dean of Hartford Seminary and Professor of Theology and Ethics December 1998-July 2001: Foundation Dean and Liverpool Professor of Theology and Public Life at Liverpool Hope University (then called Liverpool Hope University College) September 1996-December 1998: Liverpool Professor of Theology and Public Life at Liverpool Hope University September 1989-August 1996: Lecturer in Theology at University of Exeter OTHER POSITIONS The Living church Foundation, Member, Elected October, 2017. Member, St. Stephens’ & St. Agnes’ Board of Trustees: Executive Committee, Financial Aid and Enrollment Management (Chair), Buildings and Grounds, 2014 to present. Chair: Washington Theological Consortium; Executive Committee, 2012 to present. Virginia Theological Seminary: Board of Trustees: Academic Affairs Committee, Buildings and Grounds Committee, Community Life Committee, Executive Committee, Finance Committee, Institutional Advancement Committee, Investment Committee, Trustees Committee, Honorary Degrees Sub-Committee, 2007 to present. Associate Priest, St. Paul’s Episcopal Church, Alexandria, 2007 to Present. Visiting Professor of Globalization, Ethics, and Islam at Leeds Metropolitan University, September 2005 – 2008. -

1A2ae.10.2.Responsio 2

THE TRINITARIAN GIFT UNFOLDED: SACRIFICE, RESURRECTION, COMMUNION JOHN MARK AINSLEY GRIFFITHS, BSC., MSC., MA Thesis submitted to the University of Nottingham for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy July 2015 Abstract Contentious unresolved philosophical and anthropological questions beset contemporary gift theories. What is the gift? Does it expect, or even preclude, some counter-gift? Should the gift ever be anticipated, celebrated or remembered? Can giver, gift and recipient appear concurrently? Must the gift involve some tangible ‘thing’, or is the best gift objectless? Is actual gift-giving so tainted that the pure gift vaporises into nothing more than a remote ontology, causing unbridgeable separation between the gift-as-practised and the gift-as-it-ought-to- be? In short, is the gift even possible? Such issues pervade scholarly treatments across a wide intellectual landscape, often generating fertile inter-disciplinary crossovers whilst remaining philosophically aporetic. Arguing largely against philosophers Jacques Derrida and Jean-Luc Marion and partially against the empirical gift observations of anthropologist Marcel Mauss, I contend in this thesis that only a theological – specifically trinitarian – reading liberates the gift from the stubborn impasses which non-theological approaches impose. That much has been argued eloquently by theologians already, most eminently John Milbank, yet largely with a philosophical slant. I develop the field by demonstrating that the Scriptures, in dialogue with the wider Christian dogmatic tradition, enrich discussions of the gift, showing how creation, which emerges ex nihilo in Christ, finds its completion in him as creatures observe and receive his own perfect, communicable gift alignment. In the ‘gift-object’ of human flesh, believers rejoicingly discern Christ receiving-in-order-to-give and giving-in- order-to-receive, the very reciprocal giftedness that Adamic humanity spurned. -

Updated Record Book 9 25 07.Pmd

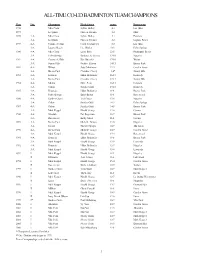

ALL-TIME CO-ED BADMINTON TEAM CHAMPIONS Year Div. Champion Head Coach Score Runner-up 1976 Mira Costa Sylvia Holley 4-1 Los Altos 1977 La Quinta Floreen Fricioni 3-2 Muir 1978 4-A Mira Costa Sylvia Holley 4-1 Estancia 3-A La Quinta Floreen Fricioni 3-2 Laguna Beach 1979 4-A Corona del Mar Carol Stockmeyer 8-5 Los Altos 3-A Laguna Beach Dee Brislen 10-3 Palm Springs 1980 4-A Mira Costa Larry Bark 22-5 Huntington Beach 3-A Palm Springs Barbara Jo Graves 17-10 Nogales 1981 4-A Corona del Mar Kim Duessler 17-10 Walnut 3-A Sunny Hills Pauline Eliason 14-13 Buena Park 1982 4-A Walnut Judy Manthorne 22-5 Garden Grove 3-A Buena Park Claudine Casey 1-0* Sunny Hills 1983 4-A Estancia Lillian Brabander 16-13 Kennedy 3-A Buena Park Claudine Casey 17-12 Sunny Hills 1984 4-A Marina Dave Penn 16-13 Estancia 3-A Colton Sandra Guidi 19-10 Kennedy 1985 4-A Estancia Lillian Brabander 11-8 Buena Park 3-A Palm Springs Daryl Barton 11-8 Rosemead 1986 4-A Garden Grove Vicki Toutz 13-6 Nogales 3-A Colton Sandra Guidi 16-3 Palm Springs 1987 4-A Colton Sandra Guidi 14-5 Buena Park 3-A Mark Keppel Harold George 13-6 Covina 1988 4-A Glendale Pat Rogerson 12-7 Buena Park 3-A Rosemead Kathy Maier 11-8 Covina 1989 4-A Buena Park Michelle Tafoya 13-6 Nogales 3-A Jordan Harriett Sprague 10-9 Alta Loma 1990 4-A Buena Park Michelle Tafoya 10-9 Garden Grove 3-A Mark Keppel Harold George 15-4 Rosemead 1991 4-A Estancia Lillian Brabander 11-8 Buena Park 3-A Mark Keppel Harold George 13-9 Etiwanda 1992 4-A Estancia Lillian Brabander 12-7 Nogales 3-A Mark Keppel Harold George -

Hearing the Call of God: Toward a Theological Phenomenology of Vocation

HEARING THE CALL OF GOD: TOWARD A THEOLOGICAL PHENOMENOLOGY OF VOCATION Submitted by Meredith Ann Secomb B.A. (Hons) B.Theol. M.A. (Psych) Theol.M. A thesis submitted in total fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy National School of Theology Faculty of Theology and Philosophy Australian Catholic University Research Services Locked Bag 4115 Fitzroy Victoria 3065 Australia March 2010 ii Statement of Sources This thesis contains no material published elsewhere or extracted in whole or in part from a thesis by which I have qualified for or been awarded another degree or diploma. No parts of this thesis have been submitted towards the award of any other degree or diploma in any other tertiary institution. No other person’s work has been used without due acknowledgement in the main text of the thesis. Signed: _____________________ Date: _____________________ iii Abstract This study contributes to the development of a theological phenomenology of vocation. In so doing, it posits that the distressing condition of existential unrest can be a foundational motivation for the vocational search and argues that the discovery of one’s vocation, which necessarily entails an engagement with existential mystery, is served by attentiveness to what is termed the “pneumo-somatic” data of embodied consciousness. Hence, the study does not canvass the broad range of phenomena that would contribute to a comprehensive phenomenology of vocation. Rather, it seeks to highlight an aspect frequently overlooked in the vocational search, namely the value of attentiveness to one’s experience of the body in the context of prayerful engagement with the mystery of God. -

Alcohol, Addiction and Christian Ethics

This page intentionally left blank ALCOHOL, ADDICTION AND CHRISTIAN ETHICS Addictive disorders are characterised by a division of the will, in which the addict is attracted both by a desire to continue the addictive behaviour and also by a desire to stop it. Academic perspectives on this predicament usually come from clinical and scientific standpoints, with the ‘moral model’ rejected as outmoded. But Christian theology has a long history of thinking and writing on such problems and offers insights which are helpful to scientific and ethical reflection upon the nature of addiction. Christopher Cook reviews Christian theological and ethical reflection upon the problems of alcohol use and misuse, from biblical times until the present day. Drawing particularly upon the writings of St Paul the Apostle and Augustine of Hippo, a critical theological model of addiction is developed. Alcohol dependence is also viewed in the broader ethical perspective of the use and misuse of alcohol within communities. christopher c. h. cook is Professorial Research Fellow in the Department of Theology and Religion, Durham University, England and a consultant psychiatrist. He is co-author of The Treat- ment of Drinking Problems, 4th edn (2003). new studies in christian ethics General Editor: Robin Gill Editorial Board: Stephen R. L. Clark, Stanley Hauerwas, Robin W. Lovin Christian ethics has increasingly assumed a central place within academic theology. At the same time the growing power and ambiguity of modern science and the rising dissatisfaction within the social sciences about claims to value-neutrality have prompted renewed interest in ethics within the secular academic world. There is, therefore, a need for studies in Christian ethics which, as well as being concerned with the relevance of Christian ethics to the present-day secular debate, are well informed about parallel discussions in recent philosophy, science or social science. -

Liberation Theology: Second Edition Edited by Christopher Rowland Frontmatter More Information

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-68893-2 - The Cambridge Companion to: Liberation Theology: Second Edition Edited by Christopher Rowland Frontmatter More information THE CAMBRIDGE COMPANION TO LIBERATION THEOLOGY Liberation theology is widely referred to in discussions of politics and religion but not always adequately understood. The new edition of this Companion brings the story of the movement’s continuing importance and impact up to date. Additional essays, which complement those in the original edition, expand upon the issues by dealing with gender and sexuality and the important matter of epistemology. In the light of a more conservative ethos in Roman Catholicism, and in theology generally, liberation theology is often said to have been an intellectural movement tied to a particular period of ecumenical and political theology. These essays indicate its continuing importance in different contexts and enable readers to locate its distinctive intellectual ethos within the evolving contextual and cultural concerns of theology and religious studies. This book will be of interest to students of theology as well as to sociologists, political theorists and historians. CHRISTOPHER ROWLAND is Dean Ireland’s Professor of the Exegesis of Holy Scripture, University of Oxford. His most recent publications include Radical Christian Writings: A Reader (2002) with Andrew Bradstock. © in this web service Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-68893-2 - The Cambridge Companion to: Liberation Theology: Second Edition Edited by Christopher Rowland Frontmatter More information © in this web service Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-68893-2 - The Cambridge Companion to: Liberation Theology: Second Edition Edited by Christopher Rowland Frontmatter More information CAMBRIDGE COMPANIONS TO RELIGION A series of companions to major topics and key figures in theology and religious studies. -

Hans Urs Von Balthasar Society

Reports of Developing or Ad Hoc Groups 273 HANS URS VON BALTHASAR SOCIETY EDWARD OAKES' PATTERN OF REDEMPTION Presenter: Edward T. Oakes Respondent: Mark A. Mcintosh Most theologians agree that their discipline is a "second-order" activity, meaning a subsequent, reasoned reflection upon the prior data of faith and revelation. Oakes introduced his book by showing how Balthasar himself handles this distinction between first- and second-order activity internal to Christian faith. As it happens, Balthasar's own degree was in Germanistik and not theology, and so it is not surprising to learn that he draws on literary categories to explain the role of theology in relation to the life of faith. In the first volume of the Theodramatik, Balthasar devotes a number of pages to a contrast between epic, lyric and dramatic modes of thought, heavily favoring the latter. The priority he gives to the dramatic mode is his way of emphasizing the first-order claims of faith: faith is first and foremost a doing, a response to a kerygma which demands obedience before it gives birth to thought. And this response is the drama of the soul saying "Yes" or "No" to God. This is why Balthasar holds that the art of drama, especially when we are speaking in poetic terms, is the highest form of art, because it encompasses all other art forms. Nonetheless, Oakes took a few moments to explore the contrast between epic and lyric styles. In the history of poetry one can notice two distinct trends that run through the course of literature: that between the civic and the private. -

Anglican Studies (ANGL) 1

Anglican Studies (ANGL) 1 Anglican Studies (ANGL) ANGL 537 C.S. Lewis: Author, Apologist, and Anglican (3) This course will examine selected writings of C. S. Lewis (1898-1963) with special attention to the historical development and Anglican character of his work. It will consider how Lewis treated certain key themes through more than one genre, focusing particularly on his apologetics, science fiction, and fantasy. Themes and texts considered will include suffering and eschatology (The Problem of Pain / The Great Divorce), natural law and posthumanism (The Abolition of Man / That Hideous Strength), theism and naturalism (Miracles / The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe), and human and divine love (The Four Loves / Till We Have Faces). ANGL 539 The Anglican Tradition of Reason: Butler, Newman, and Farrer (3) This course will examine the theological and philosophical aspects of an important tradition spanning three centuries of English Anglicanism. Focusing on the writings of three definitive figures who drew upon and shaped this tradition, we will examine Joseph Butler in the eighteenth century, John Henry Newman in the nineteenth century, and Austin Farrer in the twentieth century. All three were noted preachers and scholars, as well as original thinkers and devout churchmen; the works we read will represent these different modes and concerns of their writing. We will also examine the historical context in both church and society during their respective periods, and consider the significance and implications of this ’tradition of reason’ for Anglican theology today. This course also has the attributes of CHHT and THEO. ANGL 540 The Shape of the Communion (3) This is a course on the Instruments of Communion and how they have shaped Global Anglicanism. -

Durham E-Theses

Durham E-Theses Thomas Traherne in Tradition: An Analysis of Platonist Cognition through the Writings of Plotinus, Ficino, Traherne, and Hobbes GUERTIN, FRANK,JOHN How to cite: GUERTIN, FRANK,JOHN (2017) Thomas Traherne in Tradition: An Analysis of Platonist Cognition through the Writings of Plotinus, Ficino, Traherne, and Hobbes , Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/12260/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk 2 Abstract Since the initial discovery of Traherne at the turn of the twentieth century, studies of his work have often neglected theological and philosophical analyses. Early caricatures of Traherne as a proto‐Romantic have also colored his reception as a serious theologian. By placing the critical emphasis on the literary dynamics within the corpus, the intellectual history influencing Traherne and the construction of his ideas has subsequently been lightly addressed in scholarship over the years. -

Une Discographie De Robert Wyatt

Une discographie de Robert Wyatt Discographie au 1er mars 2021 ARCHIVE 1 Une discographie de Robert Wyatt Ce présent document PDF est une copie au 1er mars 2021 de la rubrique « Discographie » du site dédié à Robert Wyatt disco-robertwyatt.com. Il est mis à la libre disposition de tous ceux qui souhaitent conserver une trace de ce travail sur leur propre ordinateur. Ce fichier sera périodiquement mis à jour pour tenir compte des nouvelles entrées. La rubrique « Interviews et articles » fera également l’objet d’une prochaine archive au format PDF. _________________________________________________________________ La photo de couverture est d’Alessandro Achilli et l’illustration d’Alfreda Benge. HOME INDEX POCHETTES ABECEDAIRE Les années Before | Soft Machine | Matching Mole | Solo | With Friends | Samples | Compilations | V.A. | Bootlegs | Reprises | The Wilde Flowers - Impotence (69) [H. Hopper/R. Wyatt] - Robert Wyatt - drums and - Those Words They Say (66) voice [H. Hopper] - Memories (66) [H. Hopper] - Hugh Hopper - bass guitar - Don't Try To Change Me (65) - Pye Hastings - guitar [H. Hopper + G. Flight & R. Wyatt - Brian Hopper guitar, voice, (words - second and third verses)] alto saxophone - Parchman Farm (65) [B. White] - Richard Coughlan - drums - Almost Grown (65) [C. Berry] - Graham Flight - voice - She's Gone (65) [K. Ayers] - Richard Sinclair - guitar - Slow Walkin' Talk (65) [B. Hopper] - Kevin Ayers - voice - He's Bad For You (65) [R. Wyatt] > Zoom - Dave Lawrence - voice, guitar, - It's What I Feel (A Certain Kind) (65) bass guitar [H. Hopper] - Bob Gilleson - drums - Memories (Instrumental) (66) - Mike Ratledge - piano, organ, [H. Hopper] flute. - Never Leave Me (66) [H. -

The Moody Blues Tour / Set List Project - Updated April 9, 2006

The Moody Blues Tour / Set List Project - updated April 9, 2006 compiled by Linda Bangert Please send any additions or corrections to Linda Bangert ([email protected]) and notice of any broken links to Neil Ottenstein ([email protected]). This listing of tour dates, set lists, opening acts, additional musicians was derived from many sources, as noted on each file. Of particular help were "Higher and Higher" magazine and their website at www.moodies- magazine.com and the Moody Blues Official Fan Club (OFC) Newsletters. For a complete listing of people who contributed, click here. Particular thanks go to Neil Ottenstein, who hosts these pages, and to Bob Hardy, who helped me get these pages converted to html. One-off live performances, either of the band as a whole or of individual members, are not included in this listing, but generally can be found in the Moody Blues FAQ in Section 8.7 - What guest appearances have the band members made on albums, television, concerts, music videos or print media? under the sub-headings of "Visual Appearances" or "Charity Appearances". The current version of the FAQ can be found at www.toadmail.com/~notten/FAQ-TOC.htm I've construed "additional musicians" to be those who played on stage in addition to the members of the Moody Blues. Although Patrick Moraz was legally determined to be a contract player, and not a member of the Moody Blues, I have omitted him from the listing of additional musicians for brevity. Moraz toured with the Moody Blues from 1978 through 1990. From 1965-1966 The Moody Blues were Denny Laine, Clint Warwick, Mike Pinder, Ray Thomas and Graeme Edge, although Warwick left the band sometime in 1966 and was briefly replaced with Rod Clarke.