Materiality and Politics in Chile's Museum of Memory

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Power of Images in the Age of Mussolini

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2013 The Power of Images in the Age of Mussolini Valentina Follo University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the History Commons, and the History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons Recommended Citation Follo, Valentina, "The Power of Images in the Age of Mussolini" (2013). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 858. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/858 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/858 For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Power of Images in the Age of Mussolini Abstract The year 1937 marked the bimillenary of the birth of Augustus. With characteristic pomp and vigor, Benito Mussolini undertook numerous initiatives keyed to the occasion, including the opening of the Mostra Augustea della Romanità , the restoration of the Ara Pacis , and the reconstruction of Piazza Augusto Imperatore. New excavation campaigns were inaugurated at Augustan sites throughout the peninsula, while the state issued a series of commemorative stamps and medallions focused on ancient Rome. In the same year, Mussolini inaugurated an impressive square named Forum Imperii, situated within the Foro Mussolini - known today as the Foro Italico, in celebration of the first anniversary of his Ethiopian conquest. The Forum Imperii's decorative program included large-scale black and white figural mosaics flanked by rows of marble blocks; each of these featured inscriptions boasting about key events in the regime's history. This work examines the iconography of the Forum Imperii's mosaic decorative program and situates these visual statements into a broader discourse that encompasses the panorama of images that circulated in abundance throughout Italy and its colonies. -

Buddhism from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia Jump To: Navigation, Search

Buddhism From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Jump to: navigation, search A statue of Gautama Buddha in Bodhgaya, India. Bodhgaya is traditionally considered the place of his awakening[1] Part of a series on Buddhism Outline · Portal History Timeline · Councils Gautama Buddha Disciples Later Buddhists Dharma or Concepts Four Noble Truths Dependent Origination Impermanence Suffering · Middle Way Non-self · Emptiness Five Aggregates Karma · Rebirth Samsara · Cosmology Practices Three Jewels Precepts · Perfections Meditation · Wisdom Noble Eightfold Path Wings to Awakening Monasticism · Laity Nirvāṇa Four Stages · Arhat Buddha · Bodhisattva Schools · Canons Theravāda · Pali Mahāyāna · Chinese Vajrayāna · Tibetan Countries and Regions Related topics Comparative studies Cultural elements Criticism v • d • e Buddhism (Pali/Sanskrit: बौद धमर Buddh Dharma) is a religion and philosophy encompassing a variety of traditions, beliefs and practices, largely based on teachings attributed to Siddhartha Gautama, commonly known as the Buddha (Pāli/Sanskrit "the awakened one"). The Buddha lived and taught in the northeastern Indian subcontinent some time between the 6th and 4th centuries BCE.[2] He is recognized by adherents as an awakened teacher who shared his insights to help sentient beings end suffering (or dukkha), achieve nirvana, and escape what is seen as a cycle of suffering and rebirth. Two major branches of Buddhism are recognized: Theravada ("The School of the Elders") and Mahayana ("The Great Vehicle"). Theravada—the oldest surviving branch—has a widespread following in Sri Lanka and Southeast Asia, and Mahayana is found throughout East Asia and includes the traditions of Pure Land, Zen, Nichiren Buddhism, Tibetan Buddhism, Shingon, Tendai and Shinnyo-en. In some classifications Vajrayana, a subcategory of Mahayana, is recognized as a third branch. -

Architecture Et Revolution: Le Corbusier and the Fascist Revolution

This may be the author’s version of a work that was submitted/accepted for publication in the following source: Brott, Simone (2013) Architecture et revolution: Le Corbusier and the fascist revolution. Thresholds, 41, pp. 146-157. This file was downloaded from: https://eprints.qut.edu.au/55892/ c Copyright 2013 Massachusetts Institute of Technology This work is covered by copyright. Unless the document is being made available under a Creative Commons Licence, you must assume that re-use is limited to personal use and that permission from the copyright owner must be obtained for all other uses. If the docu- ment is available under a Creative Commons License (or other specified license) then refer to the Licence for details of permitted re-use. It is a condition of access that users recog- nise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. If you believe that this work infringes copyright please provide details by email to [email protected] Notice: Please note that this document may not be the Version of Record (i.e. published version) of the work. Author manuscript versions (as Sub- mitted for peer review or as Accepted for publication after peer review) can be identified by an absence of publisher branding and/or typeset appear- ance. If there is any doubt, please refer to the published source. http:// thresholds.mit.edu/ issue/ 41a.html 26/09/2012 DRAFT 1 26/09/2012 DRAFT Architecture et révolution: Le Corbusier and the Fascist Revolution Simone Brott In a letter to a close friend dated April 1922, Le Corbusier announced that he was to publish his first major book “Architecture et révolution” which would collect “a set of articles from L’EN”1—L’Esprit nouveau, the revue jointly edited by him and painter Amédée Ozenfant which ran from 1920 to 1925.2 A year later, Le Corbusier sketched a book cover design featuring “LE CORBUSIER–SAUGNIER,” the pseudonymic compound of Pierre Jeanneret and Ozenfant, above a square-framed single-point perspective of a square tunnel vanishing toward the horizon. -

Review of Hitlers Sozialer Wohnungsbau 1940-1945

Bryn Mawr College Scholarship, Research, and Creative Work at Bryn Mawr College Growth and Structure of Cities Faculty Research Growth and Structure of Cities and Scholarship 1991 Review of Hitlers sozialer Wohnungsbau 1940-1945: Wohnungspolitik, Baugestaltung und Siedlungsplanung, edited by Tilman Harlander and Gerhard Fehl; Deutsche Architekten: Biographische Verflechtungen 1900-1970, by Werner Durth; Faschistische Architekturen: Planen und Bauen in Europa 1930-1945, edited by Hartmut Frank Barbara Miller Lane Bryn Mawr College, [email protected] Let us know how access to this document benefits ouy . Follow this and additional works at: http://repository.brynmawr.edu/cities_pubs Part of the Architecture Commons, History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons, and the Urban Studies and Planning Commons Custom Citation Barbara Miller Lane, Review of Hitlers sozialer Wohnungsbau 1940-1945: Wohnungspolitik, Baugestaltung und Siedlungsplanung, edited by Tilman Harlander and Gerhard Fehl; Deutsche Architekten: Biographische Verflechtungen 1900-1970, by Werner Durth; Faschistische Architekturen: Planen und Bauen in Europa 1930-1945, edited by Hartmut Frank. Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians 50 (1991): 430-434. This paper is posted at Scholarship, Research, and Creative Work at Bryn Mawr College. http://repository.brynmawr.edu/cities_pubs/25 For more information, please contact [email protected]. BOOK REVIEWS 325 and one wonderswhy an exteriorsetting was desiredfor such ing her surprisewith the condescending"dati i tempi."In fact, a groupand whether amphitheaterswere unusualfeatures for Clement XI had commandedCarlo Fontanain 1701 not to settecentovilla gardens.Other questions rise in connectionwith obscurefrom view any partof the facademosaic of S. Mariain an anonymousTrevi projectfrom the pontificateof Clement Trasteverein the constructionof a new portico.I believe that XI that includesthe newly unearthedAntonine column. -

Rhodes Historical Review VOLUME 19 SPRING 2017

Rhodes Historical Review VOLUME 19 SPRING 2017 Entrance to the Accademia, and then to America: The Life of Mary Solari, 1849-1929 Rosalind KennyBirch Founders & Fascists in a Fuller Framework: Contextualizing the Spectrum of British Eugenic Opinions towards Nazi Practices in Light of the Field’s Foundation and Problematic Colonial Encounters Nathaniel Plemons Cedo La Parola Al Piccone: Fascist Violence on the Urban Landscape Dominik Booth The Battle for Chinatown: Adaptive Resilience of San Francisco’s Chinese Community in the Aftermath of the 1906 Earthquake Claire Carr The Rhodes Historical Review Published annually by the Alpha Epsilon Delta Chapter of Phi Alpha Theta History Honor Society Rhodes College Memphis, Tennessee EDITORS-IN-CHIEF Madeleine McGrady Adrian Scaife FACULTY ADVISORS Dee Garceau, Professor Seok-Won Lee, Assistant Professor Ariel Lopez, Assistant Professor Robert Saxe, Associate Professor PRODUCTION MANAGER Carol Kelley CHAPTER ADVISOR Seok-Won Lee, Assistant Professor The Rhodes Historical Review showcases outstanding undergraduate history research taking place at Rhodes College in Memphis, Tennessee. Phi Alpha Theta (The National History Honor Society) and the Department of History at Rhodes College publish The Rhodes Historical Review annually. The Rhodes Historical Review is produced entirely by a three-member student editorial board and can be found in the Ned R. McWherter Library at The University of Memphis, the Benjamin L. Hooks Central Public Library of Memphis, and The Paul J. Barret Jr. Library at Rhodes College. Submission Policy: In the fall, the editors begin soliciting submissions for essays 3,000-6,000 words in length. Editors welcome essays from any department and from any year in which the author is enrolled; however, essays must retain a historical focus and must be written by a student currently enrolled at Rhodes College. -

In Fascist Italy

fascism 7 (2018) 45-79 brill.com/fasc Futures Made Present: Architecture, Monument, and the Battle for the ‘Third Way’ in Fascist Italy Aristotle Kallis Keele University [email protected] Abstract During the late 1920s and 1930s, a group of Italian modernist architects, known as ‘ra- tionalists’, launched an ambitious bid for convincing Mussolini that their brand of ar- chitectural modernism was best suited to become the official art of the Fascist state (arte di stato). They produced buildings of exceptional quality and now iconic status in the annals of international architecture, as well as an even more impressive register of ideas, designs, plans, and proposals that have been recognized as visionary works. Yet, by the end of the 1930s, it was the official monumental stile littorio – classical and monumental yet abstracted and stripped-down, infused with modern and traditional ideas, pluralist and ‘willing to seek a third way between opposite sides in disputes’, the style curated so masterfully by Marcello Piacentini – that set the tone of the Fascist state’s official architectural representation. These two contrasted architectural pro- grammes, however, shared much more than what was claimed at the time and has been assumed since. They represented programmatically, ideologically, and aestheti- cally different expressions of the same profound desire to materialize in space and eternity the Fascist ‘Third Way’ future avant la lettre. In both cases, architecture (and urban planning as the scalable articulation of architecture on an urban, regional, and national territorial level) became the ‘total’ media used to signify and not just express, to shape and not just reproduce or simulate, to actively give before passively receiv- ing meaning. -

Nazi Party from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

Create account Log in Article Talk Read View source View history Nazi Party From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia This article is about the German Nazi Party that existed from 1920–1945. For the ideology, see Nazism. For other Nazi Parties, see Nazi Navigation Party (disambiguation). Main page The National Socialist German Workers' Party (German: Contents National Socialist German Nationalsozialistische Deutsche Arbeiterpartei (help·info), abbreviated NSDAP), commonly known Featured content Workers' Party in English as the Nazi Party, was a political party in Germany between 1920 and 1945. Its Current events Nationalsozialistische Deutsche predecessor, the German Workers' Party (DAP), existed from 1919 to 1920. The term Nazi is Random article Arbeiterpartei German and stems from Nationalsozialist,[6] due to the pronunciation of Latin -tion- as -tsion- in Donate to Wikipedia German (rather than -shon- as it is in English), with German Z being pronounced as 'ts'. Interaction Help About Wikipedia Community portal Recent changes Leader Karl Harrer Contact page 1919–1920 Anton Drexler 1920–1921 Toolbox Adolf Hitler What links here 1921–1945 Related changes Martin Bormann 1945 Upload file Special pages Founded 1920 Permanent link Dissolved 1945 Page information Preceded by German Workers' Party (DAP) Data item Succeeded by None (banned) Cite this page Ideologies continued with neo-Nazism Print/export Headquarters Munich, Germany[1] Newspaper Völkischer Beobachter Create a book Youth wing Hitler Youth Download as PDF Paramilitary Sturmabteilung -

Quadrante and the Politicization of Architectural Discourse in Fascist Italy

Quadrante and the Politicization of Architectural Discourse in Fascist Italy David Rifkind Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy under the Executive Committee of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2007 copyright 2007 David Rifkind all rights reserved Abstract Quadrante and the Politicization of Architectural Discourse in Fascist Italy David Rifkind Through a detailed study of the journal Quadrante and its circle of architects, critics, artists and patrons, this Ph.D. dissertation investigates the relationship between modern architecture and fascist political practices in Italy during Benito Mussolini's regime (1922-43). Rationalism, the Italian variant of the modern movement in architecture, was at once pluralistic and authoritarian, cosmopolitan and nationalistic, politically progressive and yet fully committed to the political program of Fascism. An exhaustive study of Quadrante in its social context begins to explain the relationships between the political content of an architecture that promoted itself as the appropriate expression of fascist policies, the cultural aspirations of an architecture that drew on contemporary developments in literature and the arts, and the international function of a journal that promoted Italian modernism to the rest of Europe while simultaneously exposing Italy to key developments across the Alps. Contents List of figures iii Acknowledgements xv Introduction 1 Chapter 1: Architecture, Art of the State 16 1926-1927: the Gruppo -

The Legacy of Antonio Sant'elia: an Analysis of Sant'elia's Posthumous Role in the Development of Italian Futurism During the Fascist Era

San Jose State University SJSU ScholarWorks Master's Theses Master's Theses and Graduate Research Spring 2014 The Legacy of Antonio Sant'Elia: An Analysis of Sant'Elia's Posthumous Role in the Development of Italian Futurism during the Fascist Era Ashley Gardini San Jose State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.sjsu.edu/etd_theses Recommended Citation Gardini, Ashley, "The Legacy of Antonio Sant'Elia: An Analysis of Sant'Elia's Posthumous Role in the Development of Italian Futurism during the Fascist Era" (2014). Master's Theses. 4414. DOI: https://doi.org/10.31979/etd.vezv-6nq2 https://scholarworks.sjsu.edu/etd_theses/4414 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Master's Theses and Graduate Research at SJSU ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of SJSU ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE LEGACY OF ANTONIO SANT’ELIA: AN ANALYSIS OF SANT’ELIA’S POSTHUMOUS ROLE IN THE DEVELOPMENT OF ITALIAN FUTURISM DURING THE FASCIST ERA A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Department of Art and Art History San José State University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts by Ashley Gardini May 2014 © 2014 Ashley Gardini ALL RIGHTS RESERVED The Designated Thesis Committee Approves the Thesis Titled THE LEGACY OF ANTONIO SANT’ELIA: AN ANALYSIS OF SANT’ELIA’S POSTHUMOUS ROLE IN THE DEVELOPMENT OF ITALIAN FUTURISM DURING THE FASCIST ERA by Ashley Gardini APPROVED FOR THE DEPARTMENT OF ART AND ART HISTORY SAN JOSÉ STATE UNIVERSITY May 2014 Dr. -

'Estado Novo': Cultural Innovation Within a Para-Fascist State

fascism 7 (2018) 141-174 brill.com/fasc Ideology and Architecture in the Portuguese ‘Estado Novo’: Cultural Innovation within a Para-Fascist State (1932–1945) Rita Almeida de Carvalho Instituto de Ciências Sociais da Universidade de Lisboa Funded by the Foundation for Science and Technology, Portugal (SFRH/BPD/68725/2010) [email protected] Abstract This article challenges the common assumption of the fascist nature of the Portu- guese Estado Novo from the thirties to mid-forties, while recognizing the innovative, modernizing dynamic of much of its state architecture. It takes into account the pro- lix discourse of Oliveira Salazar, the head of government, as well as Duarte Pacheco’s extensive activity as minister of Public Works, and the positions and projects of the architects themselves. It also considers the allegedly peripheral status of architectural elites, and the role played by decision makers, whether politicians or bureaucrats, in the intricate process of architectural renewal. The article shows that a non-radical form of nationalism has always prevailed as a discourse in which to express the unique Por- tuguese spirit, that of a people that saw itself as transporting Christian morality and faith across the world, a civilizing role that the country continued to fulfil in its over- seas colonies. Taking the architectural legacy of the Estado Novo in its complexity leads to the conclusion that, while the dictatorship did not dismiss modernization outright, and though it adopted what could be superficially considered fascist traits, the lan- guage of national resurgence disseminated by the Portuguese regime did not express a future-oriented fascist ideology of radical rebirth. -

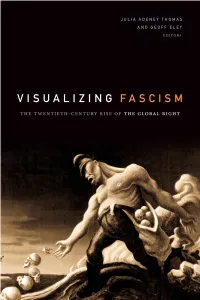

Visualizing FASCISM This Page Intentionally Left Blank Julia Adeney Thomas and Geoff Eley, Editors

Visualizing FASCISM This page intentionally left blank Julia Adeney Thomas and Geoff Eley, Editors Visualizing FASCISM The Twentieth- Century Rise of the Global Right Duke University Press | Durham and London | 2020 © 2020 Duke University Press All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America on acid- free paper ∞ Designed by Julienne Alexander / Cover designed by Matthew Tauch Typeset in Minion Pro and Haettenschweiler by Copperline Books Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Eley, Geoff, [date] editor. | Thomas, Julia Adeney, [date] editor. Title: Visualizing fascism : the twentieth-century rise of the global right / Geoff Eley and Julia Adeney Thomas, editors. Description: Durham : Duke University Press, 2020. | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers:lccn 2019023964 (print) lccn 2019023965 (ebook) isbn 9781478003120 (hardback : acid-free paper) isbn 9781478003762 (paperback : acid-free paper) isbn 9781478004387 (ebook) Subjects: lcsh: Fascism—History—20th century. | Fascism and culture. | Fascist aesthetics. Classification:lcc jc481 .v57 2020 (print) | lcc jc481 (ebook) | ddc 704.9/49320533—dc23 lc record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019023964 lc ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019023965 Cover art: Thomas Hart Benton, The Sowers. © 2019 T. H. and R. P. Benton Testamentary Trusts / UMB Bank Trustee / Licensed by vaga at Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY. This publication is made possible in part by support from the Institute for Scholarship in the Liberal Arts, College of Arts and Letters, University of Notre Dame. CONTENTS ■ Introduction: A Portable Concept of Fascism 1 Julia Adeney Thomas 1 Subjects of a New Visual Order: Fascist Media in 1930s China 21 Maggie Clinton 2 Fascism Carved in Stone: Monuments to Loyal Spirits in Wartime Manchukuo 44 Paul D. -

Move to Global War

Notum sit universis et singulis, quorum interest aut quomodolibet interesse potest, potest, interesse quomodolibet aut interest quorum singulis, et universis sit Notum postquam a multis annis orta in Imperio Romano dissidia motusque civiles eo usque usque eo civiles motusque dissidia Romano Imperio in orta annis multis a postquam increverunt, ut non modo universam Germaniam, sed et aliquot finitima regna, regna, finitima aliquot et sed Germaniam, universam modo non ut increverunt, potissimum vero Galliam, ita involverint, ut diuturnum et acre exinde natum sit bellum, bellum, sit natum exinde acre et diuturnum ut involverint, ita Galliam, vero potissimum primo quidem inter serenissimum et potentissimum principem ac dominum, dominum dominum dominum, ac principem potentissimum et serenissimum inter quidem primo Ferdinandum II., electum Romanorum imperatorem, semper augustum, Germaniae, Germaniae, augustum, semper imperatorem, Romanorum electum II., Ferdinandum Hungariae, Bohemiae, Dalmatiae, Croatiae, Sclavoniae regem, archiducem Austriae, Austriae, archiducem regem, Sclavoniae Croatiae, Dalmatiae, Bohemiae, Hungariae, ducem Burgundiae, Brabantiae, Styriae, Carinthiae, Carniolae, marchionem Moraviae, Moraviae, marchionem Carniolae, Carinthiae, Styriae, Brabantiae, Burgundiae, ducem ducem Luxemburgiae, Superioris ac Inferioris Silesiae, Wurtembergae et Teckae, Teckae, et Wurtembergae Silesiae, Inferioris ac Superioris Luxemburgiae, ducem principem Sueviae, comitem Habsburgi, Tyrolis, Kyburgi et Goritiae, marchionem Sacri Sacri marchionem Goritiae,