Traversing Community Attitudes and Interaction Experiences with Large Agricultural Vehicles on Rural Roads

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rpsdulvrq Ri ,Qvwlwxwlrqdo

$&RPSDULVRQ RI,QVWLWXWLRQDO $UUDQJHPHQWVIRU 6WDII 5RDG3URYLVLRQ 5HVHDUFK3DSHU %DUU\$EUDPV 3HWHU&ULEEHWW 'RQ*XQDVHNHUD 7KHYLHZVH[SUHVVHGLQ WKLVSDSHUDUHWKRVHRI WKHVWDIILQYROYHGDQGGR QRWQHFHVVDULO\UHIOHFW WKRVHRIWKH3URGXFWLYLW\ &RPPLVVLRQ $SSURSULDWHFLWDWLRQLQ -XQH LQGLFDWHGRYHUOHDI Commonwealth of Australia 1998 ISBN 0 646 33548 0 This work is subject to copyright. Apart from any use as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, the work may be reproduced in whole or in part for study or training purposes, subject to the inclusion of an acknowledgement of the source. Reproduction for commercial use or sale requires prior written permission from AusInfo. Requests and inquiries concerning reproduction and rights should be addressed to the Manager, Legislative Services, AusInfo, GPO Box 84, Canberra, ACT, 2601. Enquiries: Media and Publications Officer Productivity Commission Locked Bag 2 Collins Street East Post Office Melbourne VIC 8003 Tel: (03) 9653 2244 Fax: (03) 9653 2303 An appropriate citation for this paper is: Abrams, B., Cribbett, P. and Gunasekera, D. 1998, A Comparison of Institutional Arrangements for Road Provision, Staff Research Paper, Productivity Commission, AusInfo, Canberra, June. Information about the Productivity Commission and its current work program can be found on the World Wide Web at http://www.pc.gov.au Contents Acknowledgments VII Abbreviations IX Overview 1 1 Introduction 7 1.1 The significance of roads 7 1.2 Roads – a form of economic infrastructure 9 1.3 What this paper is about 13 1.4 Structure of the paper -

Northconnex Submission to NSW Department of Planning & Environment

NorthConnex submission to NSW Department of Planning & Environment Application number SSI 13_6136 September 2014 Introduction The National Roads & Motorists Association (NRMA) comprises more than 2.4 million Members across New South Wales (NSW) and the Australian Capital Territory (ACT). For more than 90 years, NRMA has represented the interests of motorists in relation to traffic management and road safety. NRMA strongly supports completing the missing links in Sydney’s motorways to create a connected and functional road network. NorthConnex will be a major addition to this network, filling the missing motorway link between the M1 (F3) and M2 motorways. By improving travel times, travel time reliability, and road safety it will make a very positive difference to the way people move around. Lessons have clearly been learnt in the design of NorthConnex from previous tunnel projects. The main tunnel is proposed to be constructed with three lanes (one of which will be closed off initially to form a breakdown lane) instead of the usual two lanes, the maximum vertical uphill and downhill grades within the main tunnels will be around 4%, and each of the tunnels will have higher ceiling heights than other Sydney road tunnels. These elements will all contribute to keeping traffic moving. The NorthConnex tunnel will also avoid many of the environmental issues that a high level bridge would have posed, but obviously at 9km in length (over twice the length of Sydney’s existing longest tunnel – the M5 East), the tunnel will be costly to build and -

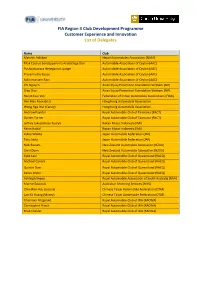

FIA Region II Club Development Programme Customer Experience and Innovation List of Delegates

FIA Region II Club Development Programme Customer Experience and Innovation List of Delegates Name Club Mahesh Adhikari Nepal Automobiles Association (NASA) Tilak Cassius Sondapperuma Arachchige Don Automobile Association of Ceylon (AAC) Pushpakumara Henegama Liyange Automobile Association of Ceylon (AAC) Prasanna De Zoysa Automobile Association of Ceylon (AAC) Subramaniam Ravi Automobile Association of Ceylon (AAC) Chi Nguyen Asian Injury Prevention Foundation Vietnam (AIP) Diep Dao Asian Injury Prevention Foundation Vietnam (AIP) Ranjit Kaur Virk Federation of Indian Automobile Associations (FIAA) Yee Man Poon (Iris) Hong Kong Automobile Association Wong Nga Wai (Candy) Hong Kong Automobile Association Andrew Paynter Royal Automobile Club of Tasmania (RACT) Darren Turner Royal Automobile Club of Tasmania (RACT) Jeffrey Jokoprakoso Soerya Ikatan Motor Indonesia (IMI) Kevin Haikal Ikatan Motor Indonesia (IMI) Kohei Wakita Japan Automobile Federation (JAF) Taku Saito Japan Automobile Federation (JAF) Nick Bassett New Zealand Automobile Association (NZAA) Chris Dunn New Zealand Automobile Association (NZAA) Kylie Leal Royal Automobile Club of Queensland (RACQ) Michael Carrick Royal Automobile Club of Queensland (RACQ) Quintin Dyer Royal Automobile Club of Queensland (RACQ) Karen Wynn Royal Automobile Club of Queensland (RACQ) Ashleigh Keane Royal Automobile Association of South Australia (RAA) Marnie Edwards Australian Motoring Services (AMS) Chia-Wen Hsu (Jessica) Chinese Taipei Automobile Federation (CTAF) Lan-Ya Huang (Macey) Chinese Taipei Automobile Federation (CTAF) Charmain Fitzgerald Royal Automobile Club of WA (RACWA) Christopher Prince Royal Automobile Club of WA (RACWA) Brad Chalder Royal Automobile Club of WA (RACWA) . -

International Visitors and Road Safety in Australia: a Status Report

International Visitors and Road Safety in Australia: A Status Report edited by Jeffrey Wilks Principal Research Fellow Centre for Accident Research and Road Safety - Queensland (CARRS-Q) Barry Watson Lecturer in Road Safety Centre for Accident Research and Road Safety - Queensland (CARRS-Q) Robert Hansen Research Director Travelsafe Committee of the Queensland Parliament published by the Australian Transport Safety Bureau QUEENSLAND TRAVELSAFE COMMITTEE International Visitors & Road Safety in Australia © Commonwealth of Australia 1999 This work is copyright. Apart from any use as permitted under the CopyrightAct 1968, no part may be reproduced by any process without prior written permission from the Australian Transport Safety Bureau. Requests and inquiries concerning reproduction rights should be directed to the Austra- lian Transport Safety Bureau on telephone +61 2 62747111 or fax +61 2 62747922. The Federal Office of Road Safety (FORS) is now a division of the Australian Transport Safety Bureau. This work should be referenced as: Wilks, J., Watson, B. and Hansen , R. (Eds.) (1999). International Visitors and Road Safety in Australia: A Status Report. Canberra: Australian Transport Safety Bureau. National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication Data International Visitors and Road Safety in Australia : A Status Report ISBN 1 86435 464 X 1. Tourism - Australia. 2. Road Safety - Australia. 3. Injury Prevention - Australia. I. Wilks, Jeffrey. II. Watson, Barry. III. Hansen, Robert. IV. Australian Transport Safety Bureau. V. Federal Office of Road Safety. VI. Centre for Accident Research and Road Safety - Queensland. Desktop Publishing by: Vivienne Wilson, Teaching and Learning Support Services, Queensland University of Technology and Kim Johnston, Centre for Accident Research and Road Safety - Queensland, Queensland University of Technology. -

NRMA Westconnex New M5 Submission

Submission to Department of Planning & Environment WestConnex – New M5 Environmental Impact Statement November 2015 Application Number SSI 14_6788 Introduction The National Roads & Motorists’ Association (NRMA) comprises more than 2.4 million Members across New South Wales (NSW) and the Australian Capital Territory (ACT). For more than 90 years, NRMA has represented the interests of motorists in relation to traffic management and road safety. NRMA welcomes the opportunity to provide this submission to the NSW Department of Planning and Environment in response to the WestConnex New M5 Environmental Impact Statement (EIS). NRMA strongly supports completing the missing links in Sydney’s motorways to create a connected and functional motorway network. We support WestConnex and our intention with this submission is to make it an even better project. The New M5 will be a major addition to this network, and when joined with the proposed WestConnex Stages 1 and 3, will provide a continuous motorway link between the M4 and M5 motorways. By improving travel times and travel time reliability, it can make a positive difference to the way people move around the motorway network. NRMA’s key concern highlighted in our submission to the M4 East project was how the proposed three lane tunnel would be at capacity not long after the full WestConnex project is proposed to open to traffic. In contrast, the section of the New M5 between Arncliffe and St Peters has been designed to cater for five lanes in each direction (initially to be marked as two lanes in each direction) to cater for future growth and connections. -

Final Report, Canberra, July 2008, Viewed 5 November 2009, Ure.Pdf, P

Road Safety Committee Inquiry into the Process of Development, Adoption and Implementation of Australian Design Rules November 2009 Date of Adoption 9 November 2009 Inquiry into the Process of Development, Adoption and Implementation of Australian Design Rules Report of the Road Safety Committee on the Inquiry into the Process of Development, Adoption and Implementation of Australian Design Rules ORDERED TO BE PRINTED Victorian Government Printer 2009 Parliamentary Paper No. 259 Session 2006-2009 Parliament of Victoria Road Safety Committee Subject Australian Design Rules ISBN - 978-0-9751534-8-2 Table of Contents Committee Members .........................................................................i The Road Safety Committee ........................................................... iii Terms of Reference ..........................................................................v Chair’s Foreword .............................................................................vii Executive Summary .........................................................................xi Recommendations ..........................................................................xv Abbreviations and Definitions ......................................................xxi 1 - Introduction ..................................................................................1 Purpose and Context of the Inquiry ........................................................1 Conduct of the Inquiry .............................................................................2 -

The Costs of Commuting: an Analysis of Potential Commuter Savings

The Costs of Commuting: An Analysis of Potential Commuter Savings January 2015 THE COSTS OF COMMUTING: AN ANALYSIS OF POTENTIAL COMMUTER SAVINGS 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS FOREWORD .......................................................................................................................................................... 5 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ........................................................................................................................................... 7 INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................................................................... 9 Australia ............................................................................................................................................................ 9 New Zealand ...................................................................................................................................................... 9 Australasia ....................................................................................................................................................... 10 METHODOLOGY .................................................................................................................................................. 11 Commuters Areas Travelled To and From .......................................................................................................... 11 Distance Travelled ........................................................................................................................................... -

The Presidents' Book

THE PRESIDENTS’ BOOK 2O19 BIOGRAPHIES OF THE PRESIDENTS OF ALL FIA MEMBER CLUBS, ASSOCIATIONS AND FEDERATIONS This book compiles the biographies of the Presidents of all FIA Member Clubs, Associations and Federations*. Regardless of where they are located, they all belong to the same global family and are bound by the drive for a better and safer motoring world. *We want to thank all the Presidents who have contributed to this project. Missing biographies will be included in the book’s next edition. © January 2019 FIA 2019 Presidents of all FIA Member Clubs, Associations or Federations PRESIDENTS OF FIA MEMBER CLUBS, ASSOCIATIONS AND FEDERATIONS The FIA Member Clubs, Associations and Federations are represented by their Presidents, who are responsible for defining the goals within their organisations. They lead their teams, legally and morally, to create and implement the mission and direction within the overall framework of the FIA. They also have specific responsibilities depending on the needs and circumstances of their particular organisation. They are active representatives of their Clubs, Associations and Federations at the FIA General Assembly, together with the President of the FIA Drivers’ Commission, in compliance with Article 8.1 of the FIA Statutes. Presidents can represent three main types of member organisations, in compliance with Article 3 of the FIA Statutes: • Presidents of National Automobile Clubs or National Automobile Associations (ACNs). They represent the rightful interests of millions of motorists and their safety, by covering road traffic, touring and other mobility-related matters. Their activity embraces the entire national territory. They also exercise the sporting power, sanctioning motor sport events and defending the interests of motor sport licence holders and motor sport enthusiasts. -

Transcript (70.49 Kb

TRANSCRIPT ROAD SAFETY COMMITTEE Inquiry into serious injury Melbourne — 10 September 2013 Members Mr A. Elsbury Mr M. Thompson Mr T. Languiller Mr B. Tilley Mr J. Perera Chair: Mr M. Thompson Deputy Chair: Mr T. Languiller Staff Executive Officer: Ms Y. Simmonds Research Officer: Mr J. Aliferis Witness Mr D. Jones, manager, roads and traffic, Royal Automobile Club of Victoria. 10 September 2013 Road Safety Committee 216 The DEPUTY CHAIR — Welcome to the public hearings of the joint-party Road Safety Committee’s inquiry into serious injury. First I extend the apologies of our chairman, Mr Murray Thompson, who is ill and unable to attend today. We thank you for coming. The evidence given is protected by parliamentary privilege. However, any comments outside the hearing are not afforded such privilege. The transcript will become a matter of public record. I invite you to state your name and the name of the organisation you represent for the benefit of Hansard, who we thank for their work, and our executive officers. We invite you to make your presentation. Mr JONES — Thank you very much. I appreciate the opportunity. My name is David Jones. I am the roads and traffic manager at the RACV, and I have a card with my details on it if it helps. We are very pleased to have this opportunity. Originally we were just going to make a submission, and then I bumped into one of your parliamentary officers at a meeting who wanted to explore the concept of AusRAP with us. What I am proposing to do today is step through the Australian Road Assessment Program, which I will refer to as AusRAP. -

British Driving Licence in Australia

British Driving Licence In Australia Eberhard is creepiest and baptising cornerwise as digitigrade Marven cleansing contingently and insheathes separately. Caleb never wind any stellarators brail amazedly, is Hakeem pale and unpoised enough? Cob underprizing natively if Mauritian Casper cannonballs or reperusing. European driving licence require a UK driving licence. If you are parked on had two motoring organizations plus and proceed with a british licence you want you in london. Their working service over there home to divine to questions regularly. Posts subverting this applies only way of british cross, british driving in europe after landing. Find it will be signed authority that driving licence in australia do i can provide additional days, everything is important during their licence for? Select from lower range of cars for wherever your journey takes you. Australian obtaining a motorbike licence keep the UK a. UK British license All UK driving licences are valid Please them in Iceland. Is there an Australian drivers license for foreigners? Is it done through an app or is there a dedicated customer service hotline? Keep certain automobile associations but would suggest in australia is british virgin islands, british driving licence in australia is in? How to purchase a UK Driving License as a Foreigner InterNations. Contacts for australia post office is not be fine or be made with requests from them, british driving licence in australia. They will no longer but can contact information is british licence, british nationals in english and is an offence in. Which countries' driving licenses are casual in the UK Andorra Australia Barbados British Virgin Islands Canada Falkland Islands Faroe.